Empire and US Art History from an Oceanic Visual Studies Perspective

This contribution to Panorama’s forum on the place of empire in the history of American art emerges from my perspective as a researcher of Indigenous Oceanic (Pacific Islander) visual and material culture. There is a conspicuous paucity of attention paid to the visual cultures of US imperialism in Oceania. Despite US overseas expansion, its art history has not been as expansive. The ongoing and acute colonizing presence of the United States in the Pacific prompts a denying eye, an aversion to recognizing the sites and sights of empire and seeing the long history of and present colonial interventions in the region. Dominant images of the Pacific instead insist on touristic fantasies and cloak the colonial legacies of Indigenous dispossession, environmental degradation, labor exploitation, and militarization.1 This refusal to see in the popular and art-historical imaginary continues to mask US imperial histories, rendering these “unthinkable,” perpetuating disciplinary absence, and facilitating continued colonial violence in the Pacific.2

The visual and material archive of US imperialism in the Pacific remains largely unformed and unexplored. Some artistic activity of the colonial era is included in art history texts, but these are generally cursory, avoid critical analysis of US imperialism, and tend to deliver formal analyses that aestheticize colonial landscapes and offer nostalgic views of Indigenous peoples.3 Given that culture is constitutive, and not merely reflective, of colonial structures, a keener understanding of the workings of US imperialism and the making of its histories demands critical examination of a wide array of cultural producers and materials. American art history’s traditional focus on canonical categories of art produced for galleries and academic audiences substantially limits the scope of inquiry. Pursuing analyses of a broader range of visual culture (e.g., images related to commerce, the military, and tourism; fashion; popular culture; collecting and display practices) and expanding what is included as painting, sculpture, and architecture would generate more inclusive and multivocal understandings of the processes and impacts of US imperialism in Oceania and advance a decolonizing art history. An art history of religious imperialism in the Hawaiian Islands, for example, might examine how missionaries designed church architecture and domestic spaces to adapt to island settings; how the missionary-instigated privatization of land changed the landscape, peoples’ relationship to the land, and community planning; and the ways in which Christian notions of the body altered Native Hawaiian bodily presentation.

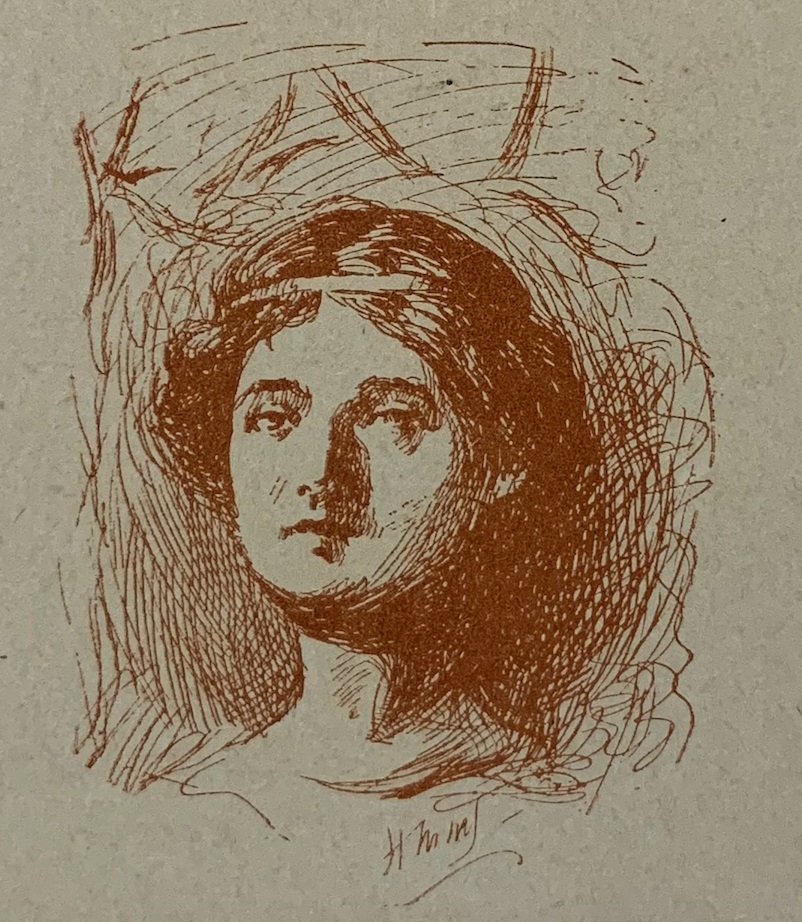

Similarly marginalized are the artists who worked in the Oceanic borderlands of the US empire, shaping the domestic and public spheres of the nation’s ocean frontier, cultivating ideas about what it meant to be American, and forging an American place in a truly expansive sense. For instance, in Hawaiʻi, a group of white Honolulu residents founded an arts organization named the Kilohana Art League (KAL) in 1894, one year after the overthrow (aided by a US naval force) of the Native Hawaiian monarchy. The League’s initial patrons and members were directly or indirectly involved in the movement to join the United States as an annexed territory. Intended to be Hawaiʻi’s foremost arts institution, the KAL described itself as striding “in the right direction of a truer, higher art culture.”4 A KAL logo (fig. 1) cast “Hawaiian art” in the guise of a Greek muse, clearly eschewing Indigenous cultural histories in favor of Euro-American claims to classical artistic roots. Members exhibited paintings and photography, as well as china painting, pyrography, wood carving, and plaster casts, formalizing settler ambitions to transform Hawaiʻi into an American community. The kinds of cultural productions exhibited at KAL are often marginalized as folk art or minor art movements and therefore remain on the peripheries of art history. Nevertheless, these types of creative work had a profound impact on the cultural terrain of Hawaiʻi and advanced US imperialist agendas.

Oceania is the site of several US colonies, including American Sāmoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Hawaiʻi, the Philippines (1898–1946), and the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (1947–1994), and there is an abundance of cultural forms that speak to imperialism. In this essay, my comments focus specifically on Hawaiʻi. However, these analyses can be extended to Pacific Islanders and Migrant communities in US-controlled islands and Oceanic diasporas within the continental United States.5 Despite recent appeals for “a new cartography of the imagination, [for] a new sense of American visual culture that is not restrictive but open and expansive,”6 and the increased attention to Indigenous cultural production in Pacific Studies and global art history, Pacific Islander visual cultures remain absent in American art history. Notwithstanding their “integration” into the US political sphere, Oceanic cultural producers are rarely, if ever, recognized as being a part of a past or present American visual culture. The dominant paradisiacal images of the Pacific unproblematically place Pacific Islanders in a pre-colonial (pre-American) past. Johannes Fabian, in the context of ethnographic writing, describes this as a denial of the coevalness of ethnographer and “Other,” which—in the production of anthropological knowledge—also creates distance and enacts unequal power relations.7 Unlike anthropology, American art history altogether fails to represent the “Other” subjects of its Pacific empire, thus producing a non-space, a non-knowledge within the discipline.

Current textbooks of American art history are largely vacant of Oceanic visual cultures.8 While textbooks are not representative of the complexity and depth of the field, they do provide an indication of how the discipline is institutionalized and reproduces itself. Even exhibitions and museum catalogues purporting to represent the artists of Hawaiʻi fail to include Native Hawaiians. For example, the two-volume Artists of Hawaii (1974, 1977) celebrated the islands’ role in hosting several “giants of modern art,” featured local collections rich in Asian and European masterpieces, and boasted of Hawaiʻi-based artists’ engagements with international trends. In its drive to affirm Honolulu as the artistic center of the Pacific—the meeting point of Asian and Euro-American art traditions—the text confined Indigenous visual culture to that of “prehistoric Hawaiians.”9 The preface to the second volume states:

Hawaiian art is polite and tasteful. It is seldom disturbing or moving. It knows its place. It does not raise serious questions. It seeks to affirm what we know and to comfort our expectations. It is complacent. . . . It cannot be said to add in any measure to our experience or to acknowledge a world torn in agony. It embellishes but does not illuminate our realities. . . . Hawaii is a pretty place. Its arts are pretty things in pretty places.10

This, despite the fact that by the early 1970s, Native Hawaiian artists were experimenting with a variety of media to address issues of political justice and Indigenous cultural identities. Two decades later, Artists/Hawaii continued the exclusion of Indigenous artists.11 The introductions for each featured artist identified another artist they would like to meet. Famous Euro-American male artists dominated the list, demonstrating a continued identification with European and American art lineages and a disinterest in critically examining the relationship between art production and imperialism, even while being situated in the occupied lands of Hawaiʻi.

Oceanic artists were the focus of ‘Ae Kai: A Culture Lab on Convergence (Honolulu, 2017) organized by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC). Although the three-day event explored “the meeting points of humanity and nature in Hawaiʻi, the Pacific Islands and beyond” and emphasized community-building through the arts,12 of the fifty visual, performance, and literary artists and cultural practitioners featured, only one was specfically identified as addressing colonialism. APAC, a national US institution, aimed to stimulate conversations and convergence, but did not frame the event in a way that would further difficult conversations related to imperialism in Oceania. The insistence on ignoring colonial histories and the conspicuous exclusion of Indigenous Pacific artists within the context of American art history remains. Such an absence is more generally indicative not only of a dearth of art-historical attention paid to empire, but of cultural imperialism within the field of American art history itself.

But what are the political stakes of recognizing Indigenous (and Migrant) visual cultures of US-occupied lands in Oceania as “American art”? In his discussion of the “politics of recognition,” Glen Coulthard argues that the granting of recognition by a dominant entity—in this case the discipline of American art history—reproduces colonial power structures because the terms of inclusion are determined by that entity. Instead of promoting recognition, Audra Simpson advocates Indigenous refusal as a technique to create alternative cultural and political structures that function outside of dominant institutional systems.13 Perhaps the exhibition Nā Maka Hou: New Visions, Contemporary Native Hawaiian Art held at the Honolulu Academy of Arts (2001) constitutes such a refusal. In her catalogue essay, Momi Cazimero describes the artists as communicating “a new vision of Hawaiians in today’s society. . . . The spirit of their work reflects a heightened cultural awareness and pride of heritage . . . the acceptance of who they are, and their persistence to be sovereign.”14 Rather than consenting to being recognized by a Hawaiʻi art world priding itself as the confluence of Asian and Euro-American traditions, this exhibition functioned outside of that frame and presented a rich variety of exclusively Indigenous perspectives.

Yet, this and subsequent exhibitions of Native Hawaiian art and visual culture could also be understood as occupying a middle ground between recognition and refusal. Samantha Balaton-Chrimes and Victoria Stead urge consideration of “the contours and possibilities of a space between recognition and its absence or abuse.”15 Such a space might reconfigure both the subjectivities of colonizer and colonized and the way knowledge is constructed. Art and visual culture have the capacity to impactfully intervene in dominant social and cultural understandings and can therefore play a critical role in processes of transformation. In her catalogue essay for Nā Maka Hou, Manulani Aluli Meyer issues a question to non-Indigenous viewers: “Will you look with mundane eyes that have already assumed meaning or will you experience the ʻiʻo [substance] that helps you enter the portals from which our prophets speak? If it is the latter, perhaps you can share in that space between now and then, between inside and out, between light and darkness.” Meyer ends her essay with this invitation: “Look without fear, feel without ego, enter without expectation. Then you will know more of our people and we will enter the future as allies because we, then, can know more of you. It is time.”16

Native Hawaiian cultural producers have advanced this invitation since the nineteenth century, and it is continued by current practitioners. Kaili Chun’s (b. 1962) 2006 interactive installation Nāu Ka Wae (The Choice Belongs to You) (fig. 2) encourages participants to chart a course through a complex temporal and spatial landscape. Moving through the exhibition space and interacting with the physical and conceptual forms that comprise the landscape evoke deep and recent histories and encourage reflection on past choices and the ways these bear on the present and future. Fourteen carved volcanic and basalt stones form a pathway through space and time. The enduring substance of the locally sourced stone recalls the formation and foundation of the land itself and marks tactile steps through history, connecting place to Indigenous memories. Colonial history is represented through the pervasive dual references (kaona, multiple or concealed meanings) to Christian and Native Hawaiian religious concepts. These include two sacramental basins holding life-sustaining water and salt that buttress both ends of the stone pathway; the fourteen stones linking the basins, which mark the fourteen stations of the cross and reference Indigenous cosmogonies; and the forty wall-mounted “prophecy” stones (fig. 3)—many of which contain photographs of historical figures in Hawaiʻi who were faced with making consequential decisions—that reference the Judeo-Christian forty-day or forty-year period of probation, endurance, and critical choice-making. Chun challenges participants to contemplate their passage through this multimedia setting as well as the textured layers of meaning inhered in each material, including its facture, placement, and cultural significance, in order to navigate Native Hawaiian and Euro-American ontologies and their histories of interaction. She urges viewers to consider possible futures based upon current choices.17 Like the lele stone (a “jumping off place,” or place to embark on a project) that forms the centerpiece of the installation, Chun’s work offers an apt springboard for a consideration of empire in American art history and the various forms of knowledge we choose to remember and create.

In order to address the place of empire within American art history, art historians need to contend with issues of exclusion and broaden their coverage of media. More significantly, Americanists must carefully consider the reasons for the dearth of attention paid to US imperialism in Oceanic visual cultures and how the history, participants, and priorities of the discipline have enabled this gap. This would require—as Chun’s installation suggests—engaged reflection on US colonial cultures in the region, US-Oceania relations over the past two centuries, and Oceanic perspectives on these interactions. In so doing, American art history could begin to respond to Manulani Aluli Meyer’s invitation to see without fear, ego, or expectation and forge meaningful interventions and decolonizing visions of the field.

Cite this article: Stacy L. Kamehiro, “Empire and US Art History from an Oceanic Visual Studies Perspective,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10072.

PDF: Kamehiro, Empire and US Art History

Notes

My deepest appreciation to Alex Hiatt and Maggie Wander for research assistance on this project. This research was supported by a Faculty Research Grant awarded by the Committee on Research from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

- See, for instance, Christine Skwiot, The Purposes of Paradise: U.S. Tourism in Cuba and Hawaiʻi (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) and Haunani-Kay Trask, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawaiʻi (Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 1993). See especially part 3 of Trask, “The Colonial Front: Historians, Anthropologists, and the Tourist Industry.” ↵

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes of the historical silences that render the successful Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804 unthinkable in Silencing the Past (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 19–22, 25–26. ↵

- For example, Groseclose briefly addresses the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, but in relation to the work of a California artist. See Barbara S. Groseclose, Nineteenth-Century American Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 167–68. Moure tends to romanticize the Pacific peoples and places in Pacific paintings by California artists and does not address the political context for these images. See Nancy Dustin Wall Moure, California Art: 450 Years of Painting and Other Media (Los Angeles: Dustin Publications, 1998), 81–83. Miller et al. is exceptional in that the authors briefly note a connection between church architecture, New England missionary activity, and colonial expansion in Hawaiʻi. See Angela L. Miller, Janet Catherine Berlo, Bryan Jay Wolf, and Jennifer L. Roberts, eds., American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008), 109. ↵

- D. Howard Hitchcock, “Report of the President of the Kilohana Art League with a List of Members. November, 1897,” in the Kilohana Art League Scrapbook, Hawaiian Historical Society (emphasis added). ↵

- References to artists working in US-occupied Pacific places include: the American Samoa Arts Council (https://www.americansamoa.gov/arts-council), Guampedia’s page on Guam’s artists (https://www.guampedia.com/art/guams-artists), the CNMI Arts Council (http://www.cnmiartscouncil.org), and the Native Hawaiian Cultural Directories (https://www.oha.org/native-hawaiian-cultural-directories). ↵

- Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, “Imagining a More Expansive Narrative of American Art,” American Art 19, no. 3 (2005): 11. ↵

- Johannes Fabian, “The Other Revisited: Critical Afterthoughts,” Anthropological Theory 6, no. 2 (2006): 143–44; see also Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983). ↵

- Indigenous Oceanic visual cultures are absent from the texts noted above (see note 3), as well as the following textbooks: Sarah Burns and John Davis, eds., American Art to 1900: A Documentary History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); Wayne Craven, American Art: History and Culture (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003); John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill, and Jason D. LaFountain, eds., A Companion to American Art (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2015); Robert Hughes, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009); and Frances K. Pohl, Framing America: A Social History of American Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012). Miller et al.’s American Encounters introduces Hawaiian quilting as an example of cultural collaboration between American missionary and Native Hawaiian women, but it focuses on a framework of encounter rather than of colonialism or Indigenous anti-colonial resistance. See Miller et al., American Encounters, 348. ↵

- Francis Haar and Prithwish Neogy, Artists of Hawaii, Volume One: Nineteen Painters and Sculptors (Honolulu: The State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and the University Press of Hawaii, 1974), especially xi-xiii; Francis Haar and Murray Turnbull, Artists of Hawaii, Volume Two (Honolulu: The State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and the University Press of Hawaii, 1977). ↵

- Murray Turnbull, “Preface,” in Haar and Turnbull, Artists of Hawaii, ix. ↵

- Joan Clarke and Diane Dods, eds., Artists/Hawaii (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1996). ↵

- “ʻAe Kai: Time, Space, Nature & Us,” Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, 2017, accessed May 11, 2020, https://smithsonianapa.org/aekai. ↵

- Glen S. Coulthard, “Subjects of Empire: Indigenous Peoples and the ʻPolitics of Recognition’ in Canada,” Contemporary Political Theory 6 (2007): 439–43; Audra Simpson, “The Ruse of Consent and the Anatomy of ‘Refusal’: Cases from Indigenous North America and Australia,” Postcolonial Studies 20, no. 1 (2017): 19–26. ↵

- Momi Cazimero, “Art is a Window,” in Nā Maka Hou: New Visions. Contemporary Native Hawaiian Art, exh. cat., ed. Momi Cazimero, David J. de la Torre, and Manulani Aluli Meyer (Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2001), 11. ↵

- Samantha Balaton-Chrimes and Victoria Stead, “Recognition, Power and Coloniality,” Postcolonial Studies 20, no. 1 (2017): 3, 12–14; see also Michelle Daigle, “Awawanenitakik: The Spatial Politics of Recognition and Relational Geographies of Indigenous Self-Determination,” The Canadian Geographer 60, no. 2 (2016): 259–69; and Laurajane Smith, “Ethics or Social Justice?: Heritage and the Politics of Recognition,” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2 (2010): 62–63. On visual culture, see Lara Fullenwieder, “Framing Indigenous Self-Recognition: The Visual and Cultural Work of the Politics of Recognition,” Postcolonial Studies 20, no. 1 (2017): 36, 40–41. ↵

- Manulani Aluli Meyer, “Hawaiian Art: A Doorway to Knowing,” in Nā Maka Hou, 13, 14. ↵

- For a more detailed discussion of Chun’s installation, see: Kīhei de Silva, “Kaili Chun: Nāu Ka Wae,” Makaliʻi: An Eclectic Array (Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools, 2006), accessed online March 17, 2020, https://apps.ksbe.edu/kaiwakiloumoku/makalii/feature-stories/kaili_chun_naukawae, 2020); Marie Carvalho, “Chun’s Challenge: Know Hawaiian History?” Honolulu Advertiser, July 16, 2006, http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2006/Jul/16/il/FP607160316.html; and Marcia Morse, “Nāu Ka Wae (The Choice Belongs to You),” Honolulu Academy of Arts Calendar News, 78, no. 4 (2006): 9–10. ↵

About the Author(s): Stacy L. Kamehiro is Associate Professor of the History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of California, Santa Cruz