Imperial Visions and Revisions

In April 2023, the National Portrait Gallery will present a major exhibition, 1898: The American Imperium (working title), marking the 125th anniversary of the year the United States became an empire with overseas territories. The exhibition explores the events that signaled the culmination of US territorial expansionism: the Spanish-American War (the War of 1898), the joint resolution to annex Hawai‘i (July 1898), and the Philippine War (1899–1902). Through a display of artworks and artifacts from US collections, including at the Smithsonian, and from Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, Hawai‘i, Spain, and the Philippines, The American Imperium will be the first large-scale, comparative study of visual culture from this pivotal era. Our goal is to examine the debates around US imperialism, alongside the experiences of peoples living in the Caribbean and the Pacific and the realities of their loss of self-determination.

For the National Portrait Gallery, a museum that explores the history of the United States through portraiture and visual biography, the significance of an exhibition like this one cannot be overstated. As Director Kim Sajet has often noted, the Portrait Gallery is not a hall of heroes. With that in mind, we are addressing a history that seems at odds with the nation’s foundational ideals and values, such as liberty, freedom, and democracy. While this is not the first time the museum has examined the influence of the United States beyond its continental borders, The American Imperium is unique because of its goal to understand the US empire within problematic, often brutal, contexts.1 It is also the museum’s first exhibition addressing the history of US territories. As co-curators of this exhibition, our approach is informed by our shared expertise in Latin American and Latinx history and art, and in American art and US military history. We consider the topic of US imperialism from the perspectives of active participants of the conquered lands, ranging from collaborators and autonomists to intellectuals who demanded a role in negotiating a new political status. We bring together topics such as land lust, war mongers, resistance fighters, anti-imperialist debates, the modernization of warfare, the commodification of war, medical trials to stop wartime epidemics, and the use of education as an imperial tool. We also deconstruct terms such as “benevolent assimilation” and “pacification” to probe how they mask the transformation of the United States from republic to empire. Within these curatorial parameters, we intend to challenge the notion that the United States was deploying military action in order to liberate nations from the tyranny of Spanish rule.

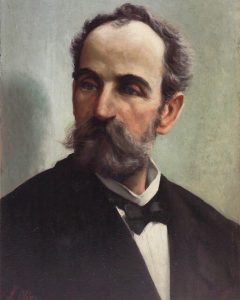

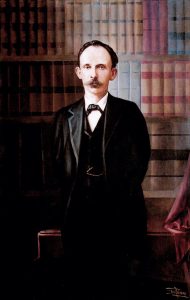

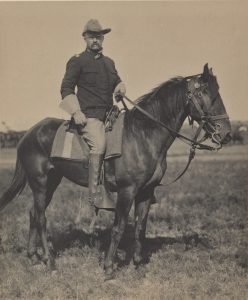

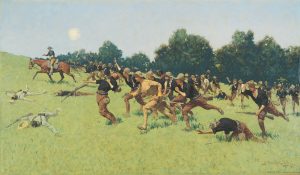

Although objects are subject to change as we confirm logistics, we plan to create an exhibition that charts a debate from a variety of viewpoints. For example, we will counterpose portraits of champions of independence—such as Puerto Rican sociologist and political activist Eugenio María de Hostos (fig. 1), Cuban thinker and writer José Martí (fig. 2), or Filipino revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo (fig. 3)—against commanding images glorifying US warfare, such as the equestrian portrait of Theodore Roosevelt by Pach Brothers’ Studio (fig. 4) or Frederic Remington’s dramatic The Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill (fig. 5). Accompanied by 150-word biographical labels, such juxtapositions problematize popular US narratives of 1898. One such myth centers on a valiant, hypermasculine Theodore Roosevelt leading the Rough Riders to victory over Spanish colonialism in Cuba.

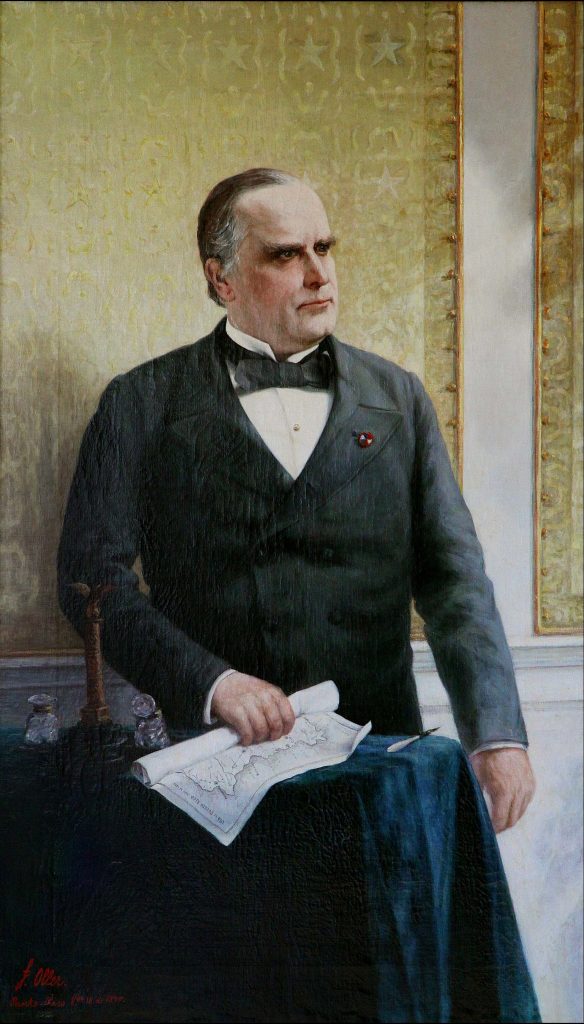

By showing portraits of US, Filipino, Puerto Rican, and Cuban leaders who were either moderate negotiators or hardline revolutionaries, we highlight how nineteenth-century anti-Spanish reformist and independence movements resisted US intervention. These movements are underrepresented in mainstream US history. In Puerto Rico, for example, the US occupation brought about an abrupt end to the self-government inaugurated by the 1897 Autonomist Charter, which Luis Muñoz Rivera and the autonomist movement had fought for through the 1890s. A portrait of Muñoz Rivera by Fernando Díaz Mackenna reminds audiences of this history. In contrast, a portrait of President William McKinley (fig. 6), gripping a map of Puerto Rico, highlights artist Francisco Oller’s perspective. As someone who witnessed and perhaps questioned his island’s political transition from a Spanish to a US colony, Oller also had to secure a living from portrait commissions of the new administration.2 We also include documents such as the 1903 Platt Amendment, which ended US military occupation and established Cuban independence on the condition that the United States be allowed to intervene in Cuban affairs and lease or buy lands for its naval bases. Such documents point to the kinds of congressional actions and Supreme Court decisions that built up the US sphere of influence and codified its empire.

Concurrently in Hawai‘i, imperialists like Lorrin Thurston and Sanford Dole were building upon the decades-long suppression of native self-determination by US missionaries and the plantation-owning elite. Labels accompanying their portraits explain how they led pro-US organizations to dethrone Queen Liliʻuokalani by threat of force in 1893 and establish a Provisional Government. Eventually, Hawai‘i became a territory and then a state. From 1893 on, the display of portraits of King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani (fig. 7) was an act of protest and signaled loyalty to the monarchy. If they had no likeness, people would display quilts with the Hawaiian royal coat of arms instead. The sovereignty movement continues to this day. Although Hawai‘i was not directly involved in the War of 1898, its annexation happened during the war, and the islands served US military purposes as a coaling station and a site of tariff-free trade.

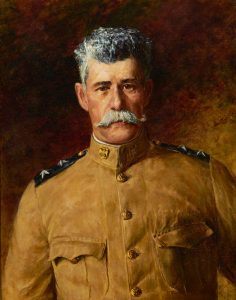

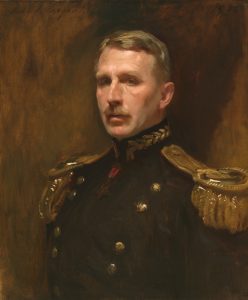

A prolonged conflict in the Philippines followed the War of 1898. Portraits of military figures like Henry Lawton by Charles Harold L. MacDonald (fig. 8) and Leonard Wood by John Singer Sargent (fig. 9) displace the realities of bloody warfare and heroize men who, arguably, had stained military careers. When displayed next to photographs of the carnage of the Philippine War, such paintings point to the abuses of power used during pacification campaigns. Extant portraits—like those of Lawton and Wood—most often represent victors who resided in the continental United States. In light of the absence of portraits of Filipino military leaders, such as General Vicente Lukban, who masterminded guerilla warfare on Samar, we have secured objects, including weapons used by Filipinos.

In addition to collections held within the continental United States, we have traveled to archives and collections in Honolulu, Lihue, metro Manila, Hagåtña, San Juan, Ponce, Bayamón, Madrid, and Seville. Additional trips to Havana and Santiago are pending. In total, we have looked at hundreds of objects from at least seventy-two collections. However, we discovered that many of the artworks and documents in the best condition were those pillaged by American soldiers. Their provenance is a direct consequence of colonialism.For example, in order to fully represent the Filipino experience, we must turn to archives that are, in effect, the spoils of war. As most Filipino archives were destroyed during World War II, the only major collection pertaining to revolutionary Filipino history is held in the Library of Congress. After these documents were seized from Filipino revolutionaries during the Philippine War, Elwell S. Otis, Military Governor of the Philippines and chief strategist of the US occupation from 1898 to 1900, instructed John R. M. Taylor to collate the two hundred thousand original documents and translate them for the US Department of War and the Senate.3 Now known as the Philippine Insurgent Records, the collection was not published until 1968. These documents hold rare and privileged information about guerilla tactics, military philosophy, and a uniquely Filipino understanding of warfare. This is especially important because, to date, there is no authoritative military history of this war from a Filipino point of view. Taylor’s account reveals both a Filipino desire for independence and a history of disunity, due to rivalries, feuds, and factions, including warring villages. The Philippine War remains relevant to contemporary US “peacekeeping” interventions in Southeast Asia.4

The question of how to make ethical use of artifacts that are spoils of war and imperialism remains one of the ironies of 1898: The American Imperium. While we don’t have an answer that will resolve this ethical conundrum, we intend to incorporate language into object labels that identify such materials as resulting from the spoils of war. We also intend to incorporate the voices of native stakeholders into didactic materials and catalogue texts.

There is no single truth to war. As the center of global power shifted from Europe to the American hemisphere at the turn of the twentieth century, Spain saw its colonial empire decimated. Even today, Spaniards refer to the conflict as “El desastre.” Similarly, from the perspective of many Native Hawaiians, Chamorros (natives of Guam), and Puerto Ricans, the exalting US narrative of benevolent conquest in order to establish democracy does not reflect the realities of political disempowerment. Finally, the expansion of military and governmental control beyond US continental borders also galvanized economic and cultural changes in these newly acquired territories. By placing portraits of key figures such as William McKinley, Emilio Aguinaldo, Queen Liliʻuokalani, Luis Muñoz Rivera, and José Martí into conversation with one another, we hope to create discourse about US imperialism. Our comparative visual approach will reveal overlooked intersections and instill new awareness about these histories.

Cite this article: Taína Caragol and Kate Clarke Lemay, “Imperial Visons and Revisions,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10096.

PDF: Caragol and Lemay, Imperial Visions and Revisions

Notes

The authors would like to thank Carolina Maestre for her assistance in researching this exhibition.

- For example, ”Dressed for the Image: Marlene Dietrich” examined the life of Marlene Dietrich in the contexts of World War II and the American intervention and defeat of European fascism, and “Portraits of the World: Korea” highlighted the work of pioneering South Korean feminist artist Yun Suknam and explored connections with US feminist artists who inspired her. ↵

- See Edward J. Sullivan, “Conflicted Affinities: Francisco Oller and William McKinley,” in From San Juan to Paris and Back: Francisco Oller and Caribbean Art in the Era of Impressionism, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 159–78. ↵

- The book’s galley proof, finished in 1906, was published in microform in 1968 by the National Archives. Although the five-volume account was ready for publication in 1906, the Secretary of War, William H. Taft did not approve its publication. This is because it chronicled numerous atrocities that the Filipino leaders committed against their own people. The War Department thus withheld a major documentary record pertaining to the Philippine Revolution and Philippine War because it was thought that it would threaten cordial Philippine-U.S. relations. See James C. Biedzynski, “Taylor, John R. M., The Philippine Insurrection Against the United States,” in Benjamin R. Beede, The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898–1934: An Encyclopedia. (New York: Taylor and Francis, 1994), 537. ↵

- Recent US professional military school publications present the Philippine War in order to help military officers understand guerilla warfare in the Middle East. See Robert D. Ramsey III, Savage Wars of Peace: Case Studies of Pacification in the Philippines, 1900–1902 (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2007). ↵

About the Author(s): Taína Caragol is Curator of Painting and Sculpture and Latinx Art and History at the National Portrait Gallery, and Kate Clarke Lemay is Historian at the National Portrait Gallery