Renée Ater

In the context of the recent Confederate memorial debates, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, directly challenges the heroic narrative of the Confederacy as an honorable struggle and the idea that slavery was a benevolent institution. Instead, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the creators of the memorial, empathetically assert that slavery and racial terror lynchings were carried out in the name of white supremacy and hate. Upending the validity of the Lost Cause ideology, the memorial asks us to consider lynching of African Americans as an essential and unavoidable aspect of American history. The power of the memorial lies in its solemn insistence that we must acknowledge and recognize the black victims of lynching in order to find redemption as a nation. Black lives matter here in a fundamental way.

The memorial opens with a quotation in bronze letters from Martin Luther King Jr., placed along a wooden slat wall that reads: “True Peace Is Not Merely the Absence of Tension, It Is the Presence of Justice.” This quotation frames the meaning of the memorial and the overall activist mission of EJI, who are “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.” The memorial space is unidirectional, with visitors passing King’s remarks to begin a slow climb up the gently sloped landscape. This quotation sets up the longue durée of the black freedom struggle that undergirds the memorial: the push for civil rights and equality are traced from slavery to sharecropping and tenant farming to convict leasing to segregation to the battle against mass incarceration of African Americans.

As visitors begin the climb to the memorial, they encounter a series of large gray plaques with white lettering that outline a brief history of slavery, labor exploitation, racial violence, and mass incarceration. The texts pull no punches—visitors are meant to confront the difficult historical facts of slavery and lynching before they enter the memorial. In front of the first plaque, the artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo has created a multifigure, standalone monument to the transatlantic slave trade. Entitled Nkyinkyyim Installation (2018), this work presents eight seminude African figures that are enchained for the harrowing journey to the coast for transportation across the Atlantic. Based on the slavery memorial in Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania, Akoto-Bamfo’s memorial evokes the abjection of slavery with its anguished expressions, chained bodies, and slashed backs. After walking past this sculpture, another large wall plaque informs visitors that white citizens murdered four thousand–plus African Americans between 1877 and 1950. The label reads, in part, “Racial terror lynchings were directly tied to the history of enslavement and the re-establishment of white supremacy after the Civil War.”

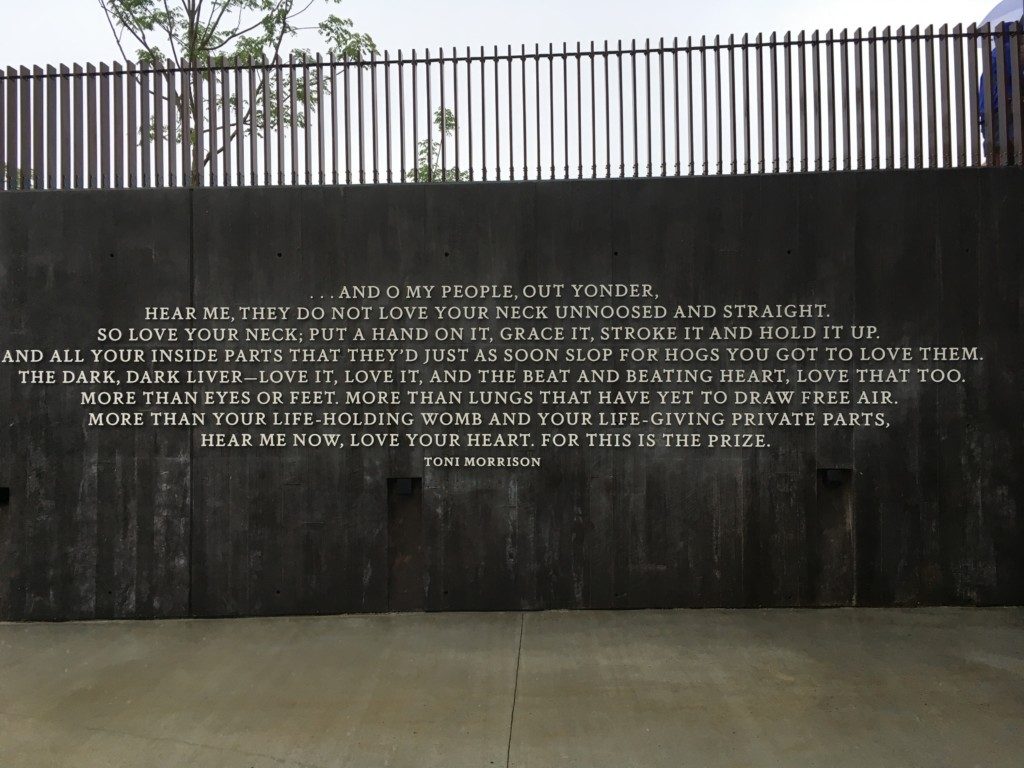

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is intentionally conceived as a sacred space for recognition of the dead, many of whom remain unnamed. Visitors are informed on numerous signs that “this memorial is a sacred space” and to act accordingly. The temple-like structure of the memorial is deeply affective in that it provides an evocative space that encourages visitors to locate themselves within the past in order to find personal, familial, and national healing in the present (see www.reneeater.com/on-monuments-blog). In the interior, the hanging rusted steel steles are a gut-wrenching reminder of black bodies hanging from trees, bridges, and platforms. Etched on each stele are the counties and states as well as the names of individuals and the dates of their murders. It is a memorial that tears at the heart, for in its naming of individuals and locations, it makes real that which had been hidden or obscured in the past. It asks us to remember, to fight for justice, and, surprisingly, to open our hearts to love, exemplified in a final quotation from Toni Morrison’s Beloved that graces a wall as visitors exit the main memorial:

And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up. And all your inside parts that they’d just as soon slop for hogs, you got to love them. The dark, dark liver—love it, love it, and the beat and beating heart, love that too. More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. More than your life-holding womb and your life-giving private parts, hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize.1

Cite this article: Renée Ater, untitled essay, “Bully Pulpit,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1635.

PDF: Ater, Bully Pulpit

Notes

- Toni Morrison, Beloved (1987; New York: Vintage Books, 2004), 104. ↵

About the Author(s): Renée Ater is Associate Professor Emerita of American Art at the University of Maryland.