A Collaborative Creation of Home: Recognizing the Multifarious Roles and Representations of Jessie Tanner

PDF: Winn, Collaborative Creation of Home

As the son of a prominent bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, Henry Ossawa Tanner was well versed in Scripture and biblical history. Throughout his long and evolving career, the artist returned to religious themes and passages that held personal significance to him, often representing biblical figures and struggles that served as creative meditations for his own challenges, triumphs, and principles. The painter’s connection with the New Testament figure Lazarus has long interested me. It was Tanner’s investment in portraying Lazarus and his sisters, Martha and Mary, that granted me a new perspective on the artist’s work and his personal convictions. I will examine three of Tanner’s paintings featuring Martha and Mary to explore how the artist invited his viewers to reconsider Belle Époque social norms, which privileged whiteness and male prerogatives, by representing a biblical past in which race was unproblematically diverse and ambiguous, but also where women were active contributors and equal participants in the story of Christ.1 I argue that this major transformation in Tanner’s oeuvre occurred after 1899, the year he married Jessie Macauley Olssen.

Tanner first earned international acclaim for his canvas The Resurrection of Lazarus at the 1897 Paris Salon. During the early twentieth century, while the artist’s connection with Lazarus persisted, his focus shifted from the theatricality of the disciple’s resurrection to lessons Jesus shared within Lazarus’s home in Bethany. This change resulted in the creation of three known canvases and several surviving esquisses that portray events from Christ’s visit to the home of Lazarus, Martha, and Mary, recounted in the Gospel of Luke (10:38–42).

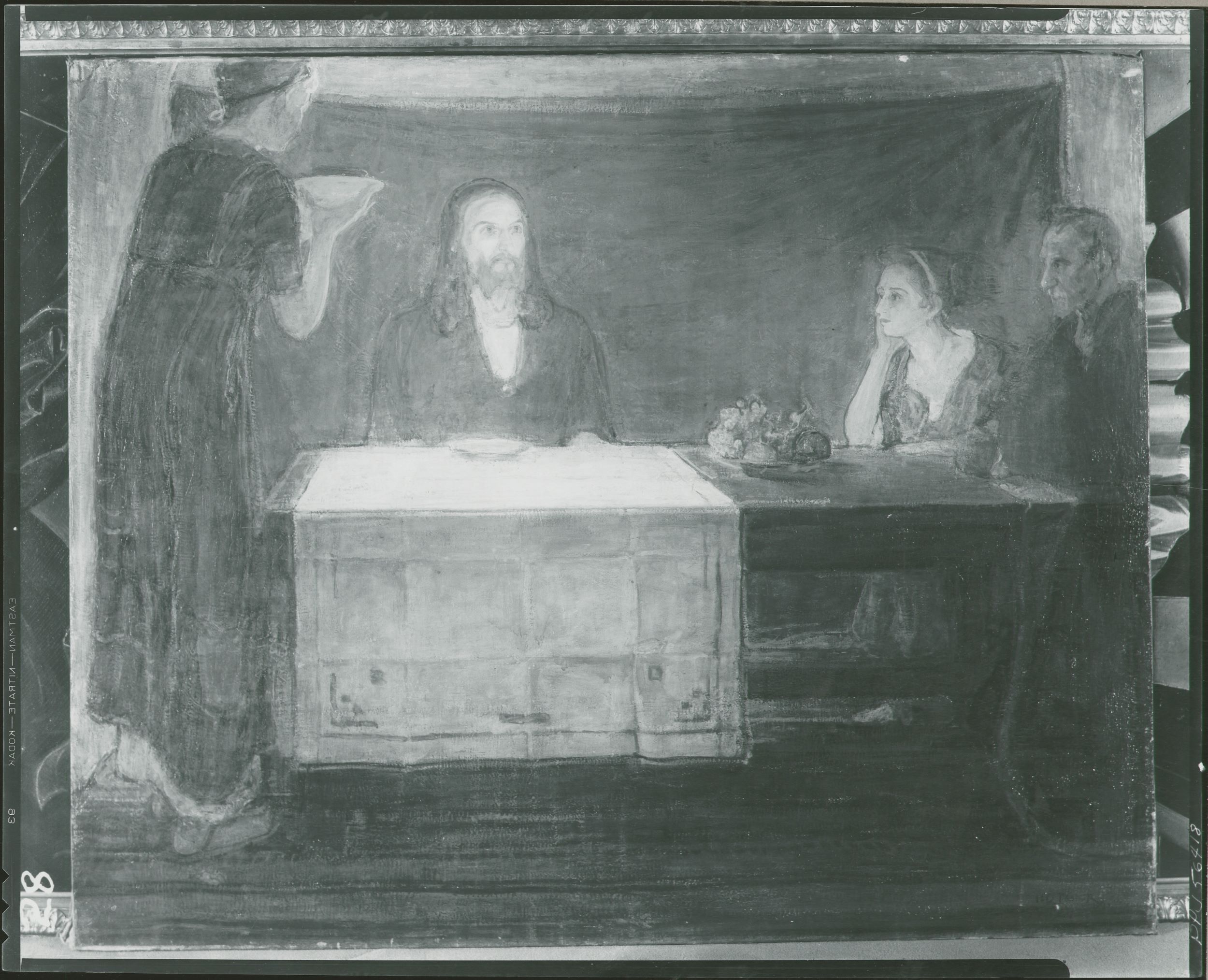

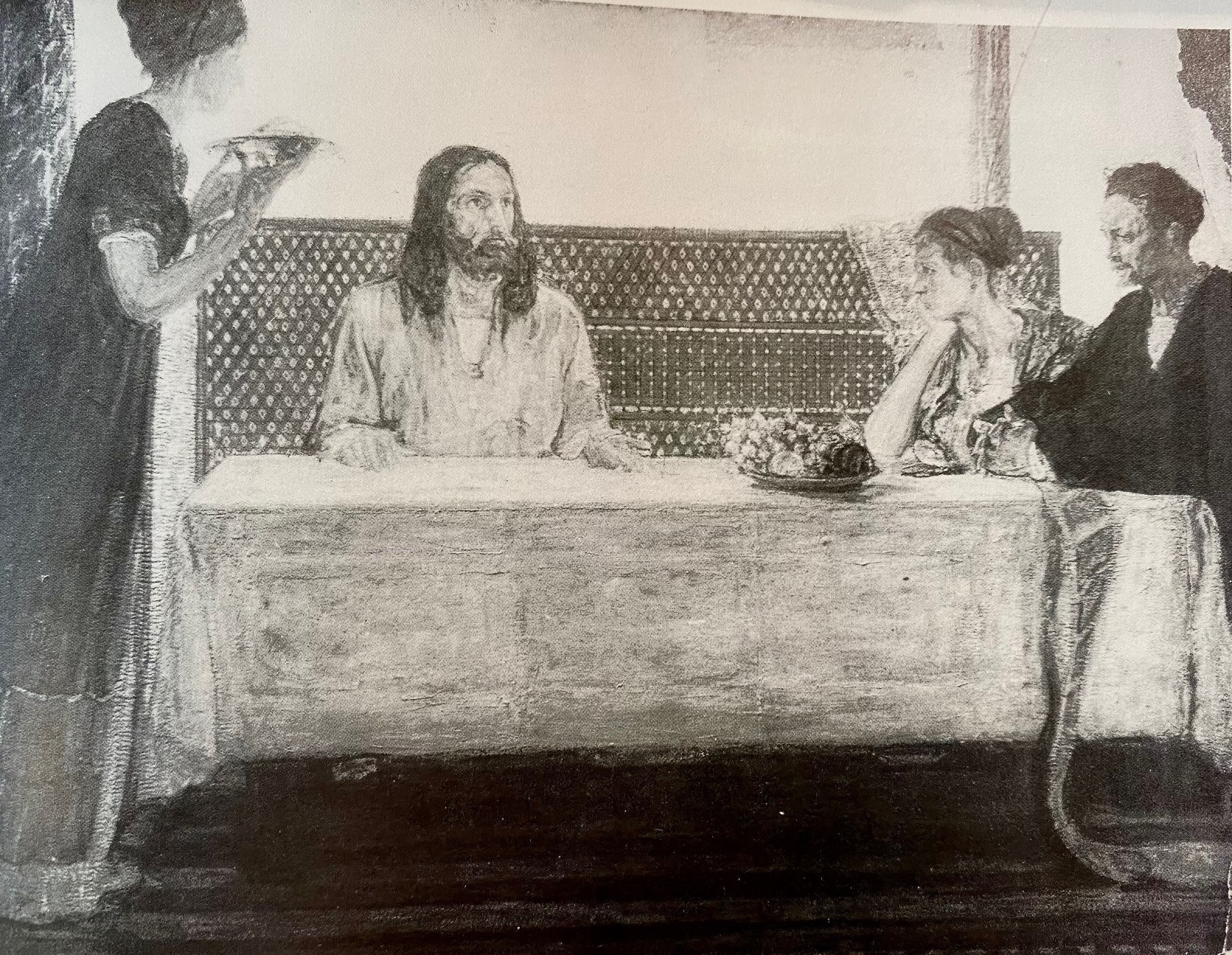

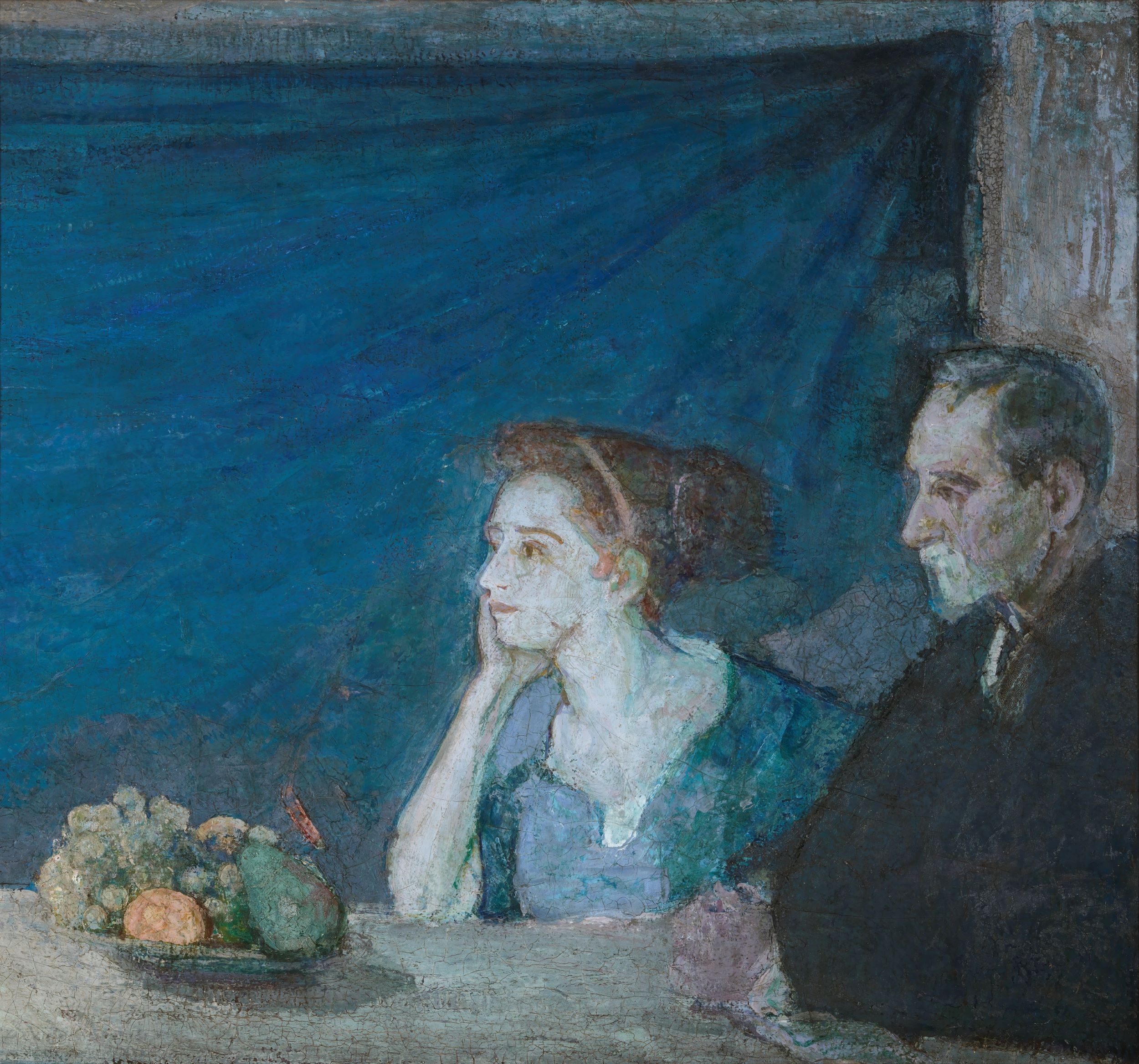

The first and only surviving canvas of this narrative, Christ at the Home of Martha and Mary from 1905 (fig. 1), is now part of the Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection in Pittsburgh. The 1912 and undated versions of Christ at the Home of Lazarus are preserved only through black-and-white archival photographs (figs. 2 and 3). Considering the three works collectively, the extant Carnegie canvas is distinct from these later paintings. Unlike the lost versions, the Carnegie painting is vertical in composition, darker in palette, and—most significantly—omits the figure of Lazarus to feature Martha and Mary’s direct connection to Christ within a shadowy domestic interior.

In examining the heavily worked surface of the canvas and the pentimento located behind the figure of Jesus, it becomes clear that Tanner did not just exclude Martha and Mary’s brother from the composition but chose to erase and paint over the figure of Lazarus.2 Discovering this anomaly within the series of paintings that feature Martha and Mary led me to further questions regarding the artist’s approach to gender within the context of Belle Époque society and a desire to highlight previously unrecognized influences and contributions to his oeuvre.

Tanner’s artistic legacy is now recognized within the study of US and Black histories of art due, in large part, to the groundbreaking scholarship of the late twentieth century and the recent critical exploration of his work in conjunction with the 2012 Modern Spirit exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia.3 The autobiographical connections between the artist’s religious imagery and his struggles to overcome racial inequality have been well established. Recently, Alan Braddock has convincingly argued that the representation of diversity and “hybridity” in Tanner’s biblical narratives, especially as it pertains to the racial identity of Christ, was an artistic strategy in “the displacement and deconstruction of race itself.”4 While the majority of scholarship on Tanner remains centered on the artist’s relationship with religion and racial identity, I aim to expand on Braddock’s approach to the “cosmopolitan” representation of race in Tanner’s imagery to account for the strategic choices he made to include, and often focus on, female figures when portraying the traditionally male-dominated narratives of biblical antiquity.

Considering the Belle Époque social context and goals espoused by first-wave feminism, I am not suggesting that Tanner’s intent was to deconstruct the male/female binary; rather, he sought to encourage gender parity by normalizing and making visible the active participation and contributions of women in his art. The artist’s representation of racial diversity and investment in universals challenged late nineteenth-century notions of racial purity; however, when taking into account the major changes that occurred in Tanner’s life during the turn of the century, there is also the potential to understand the artist’s “cosmopolitanism” as inclusive in its advocacy for gender equality. Scholars have previously made note of Tanner’s affinity for the Virgin Mary and the employment of his wife, Jessie, as a frequent model for these representations. Nevertheless, analyses and explanations as to why the artist made these shifts in his oeuvre and gravitated toward the representation of biblical women during the early twentieth century have yet to be fully explored.5

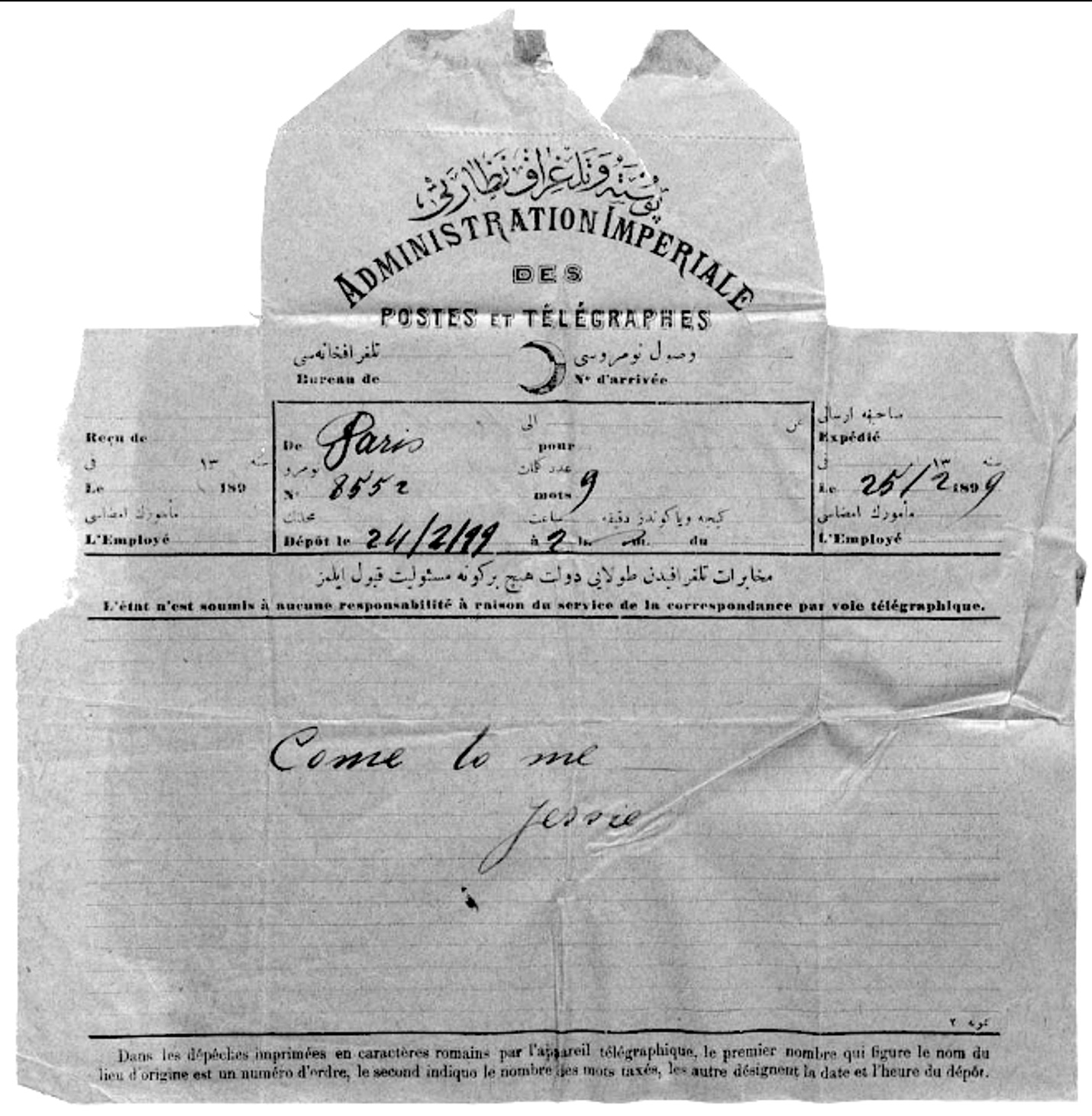

In the spring of 2017, as part of my dissertation research, I endeavored to make my way through the more than 2,500 images that comprise the Tanner papers in the Archives of American Art (AAA)’s digitized collection.6 While this collection is full of invaluable primary-source material, including candid photographs of the artist’s family and circle of friends in both the United States and France, a single document in the form of a telegram sent to the artist from his future wife transformed the way I think about Tanner, his artistic goals, and Jessie’s integral role in his work during the early twentieth century.

The telegram was sent to the artist in late February 1899, from Paris to Jerusalem, during Tanner’s second artistic pilgrimage to the Holy Land (fig. 4). Jessie’s three-word message—“Come to me”—was bold and provocative, antithetical to the artist’s own reserved character, which I had come to understand as practiced and polished but also introverted and even reticent. As my eyes traced their way through the hand-written cursive letters of Jessie’s unguarded request, I thought about how he must have felt reading these words while in a foreign land, thousands of miles away from Jessie. The importance Henry placed on Jessie’s message is evidenced by the way he safeguarded and preserved the original telegram in his personal belongings for the remainder of his life. The document was donated to the AAA among thousands of materials organized by the couple’s son, Jesse Tanner, with his annotation on the back of the telegram: “love letters, trip to Palestine.”7

The intimacy and authenticity of Jessie’s telegram brought into full color the joy, affection, and admiration imbued in so many of the artist’s works that were created during his twenty-six-year partnership with Jessie. She was a consistent presence in Tanner’s art, both literally and figuratively, and was vital in inspiring his investment in the representation of biblical women. In contemplating the effect Jessie’s telegram had on the artist and the couple’s relationship, I now perceive Tanner’s artistic goals as even richer: more than solely acting as visual manifestations of his struggles for racial equality, I believe his works also advocated for the rights and opportunities available to women at the beginning of the twentieth century. Moreover, the question of why Tanner made the decision to remove the figure of Lazarus from the Carnegie canvas and then reintroduce him into subsequent compositions when representing the same Gospel narrative became more nuanced as I explored the artist’s family history and personal correspondences.

Before the artist met his wife in 1898, he was already well acquainted with the intellectual and cultural achievements of women. Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, the artist’s grandniece, provides a detailed account of the Tanner family’s history, highlighting the groundbreaking achievements of the Tanner women who overcame the gender and racial limitations imposed on them to become successful doctors, lawyers, and published authors. Henry Tanner was raised in a home that fostered generations of women to defy the social norms of their time and achieve educational and professional firsts for Black women in the United States.8 This foundational environment, cultivated within his family’s Philadelphia home, set the stage for Tanner’s interest in portraying strong female figures, yet it was his own courtship, marriage, and creation of a home in France with Jessie that seems to have unlocked a deeper, more personal commitment in Tanner’s understanding of the “other sex.”

When Tanner set sail for Europe in 1891, he surely never imagined that he would not return to live permanently in the United States. Early accounts of his time in France offer insight into his struggles and loneliness. In an autobiography published in World’s Work, Tanner confesses:

I felt what it was to be a stranger in a strange land. . . . How strange it was to have the power of understanding and being understood suddenly withdraw! The strangeness of it, perhaps, is what made me feel so isolated.9

To assuage this feeling, the artist threw himself into his work. During the summer of 1898, he traveled to the Fontainebleau Forest to escape the heat and congestion of Paris. It was in the idyllic Barbizon landscape that Tanner first met his future wife.10

Jessie Olssen was a white woman of Swedish American descent who was raised in San Francisco. An accomplished opera singer, she traveled that summer to Germany with her sister for musical studies. When her father’s business required him to return to the United States, the family traveled to Paris and then down to the Barbizon region where they first met Tanner.11 Despite their very different personalities, Jessie and Henry’s encounter must have been agreeable because they arranged to meet again. Marcia Mathews, who published one of the first monographs on Tanner, describes Jessie as, “tall, attractive, and talented. Her warmth and spontaneity were in contrast to Tanner’s gentle reserve.”12 She continues, “The difference in their personalities seems to have acted as a magnet between them.”13 Before long, the two were inseparable.

The couple’s courtship was interrupted in October 1898 when Tanner’s patron, Rodman Wanamaker, suggested he return to Palestine for further study and offered to finance his travel. It seems the artist once again threw himself into his studies, perhaps as a distraction from Jessie’s absence. However, the telegram Jessie sent the artist in late February 1899 makes it clear they had not forgotten about each other. Her message, “Come to me,” eliminated any inhibitions the shy, modest artist may have had in proposing marriage. The couple was reunited in France when Tanner returned from the Middle East in March, and on December 14, 1899, Henry and Jessie were married at Saint Giles-in-the-Fields, Bloomsbury, London.

Through the travels, triumphs, and struggles they shared, the couple’s twenty-six-year relationship and artistic collaboration appears to have been happy. Contemporaries described the complementary nature of their union, defining it as one of “equal talents.”14 Jessie’s outgoing and gregarious character seems to have made Henry not only more sociable but also more accessible to journalists and aspiring artists. It was after their marriage that Helen Cole, writer for Brush and Pencil, provided her US audience with one of the first artistic profiles on Tanner.15 Cole describes Tanner’s work ethic and shyness, which she notes had improved over the years, no doubt due to Jessie’s influence and sociability. Jessie’s role in encouraging Henry to be more accessible advanced his professional standing and social ties with fellow artists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Beginning in 1900, the Tanners spent their summers in the fishing village of Trépied near the coastal artists’ colony of Étaples in northern France. In 1904, Henry purchased property in the village and collaborated with other expatriates to establish the Société Artistique de Picardie. Several US artists took up residence near the couple, forming what became known as the US colony of Trépied. With Jessie’s orchestration, the Tanner home in Trépied became a place for friends, relatives, patrons, journalists, and colleagues to converge. Before the outbreak of World War I disrupted the idyllic and creative synergy of the village, the Tanners were known to frequently host gatherings that established them as pillars of the Trépied community (fig. 5).16

During these prosperous and peaceful years in Trépied, Henry strove to highlight the multifarious roles Jessie played in his life by integrating her likeness and character into his religious imagery. While helping the artist advance his career and create a home in France, Jessie served as muse and model for his biblical works, representing Salome, the Virgin Mary, Rachel, Hagar, Sarah, Mary Magdalene, and Martha.17 The diverse roles Jessie played in her husband’s life and art suggested that she was all of these things to him and more.

After recognizing Jessie’s impact, I began to interpret Tanner’s devotion to portraying Lazarus’s sisters, Martha and Mary, as an homage to the couple’s collaborative partnership. The creation of Christ at the Home of Martha and Mary coincided with the artist’s employment of Jessie as the model for the biblical women in his Mothers of the Bible series for the Ladies’ Home Journal. The similarity in the appearances of Martha and Mary in this composition with photographic images of Jessie (fig. 6) makes it reasonable to attribute her as the model for both sisters. In this painting, Henry references Jessie literally and figuratively. By painting his wife’s physical likeness and presence into the image twice, Tanner visualized Jessie’s intellectual character and her supportive contributions to their home in the erudition and service of the biblical sisters.

The Carnegie canvas (see fig. 1) situates this narrative from the Gospel of Luke within a modest and shadowy but warm and hospitable candlelit domestic interior. To the right, Christ is portrayed in profile, seated across the table from Mary, who appears absorbed by his presence in their home. Christ locks eyes with and extends his hand to Martha, who stands next to her sister with a stern expression and a serving dish in her hands. In the background, behind the figure of Christ within the threshold of an interior archway, Tanner added layers of paint to suggest flickering, mottled candlelight being cast throughout the home.

Despite the heavily worked surface, the pentimento of a male figure—presumably Lazarus—remains visible under the layers of paint in the archway. Tanner’s decision to first include and then paint over the figure is perplexing. While the removal of Lazarus from the Carnegie canvas alone is not substantive evidence for Tanner’s beliefs on gender equality, when taken into consideration with the personal developments in Tanner’s life—most significantly his marriage to Jessie and the couple’s investment in creating a home abroad in France to raise their son—this decision can be understood as one of many in the artist’s work during the turn of the century in which he shifted focus to biblical narratives that included and highlighted women.

For instance, the Gospel of Luke highlights Mary’s desire to learn from Christ, describing her as sitting “at the Lord’s feet listening to what he said.”18 But in the Carnegie canvas, Tanner takes artistic license, diverging from the Gospel by positioning the figure of Mary seated at the table with Christ. In elevating Mary and granting her a “seat at the table,” Tanner’s artistic revision to the Scripture emphasizes not just her worthiness but, by extension, all women’s capacity for intellectual and spiritual pursuits. As he did in other turn-of-the-century paintings of New Testament episodes, Tanner portrayed women as present in these narratives and as active students of Christ, exhibiting behaviors of traditional rabbinic practice reserved for men in first-century Judaism.19 This rejection of gendered social norms is here emphasized by Martha’s frustration and distressed expression due to Mary’s desire to intellectually engage with Christ instead of assisting her with the traditional feminine role of service.

Tanner even created several canvases that present biblical women not just as active learners but as conferrers of knowledge. He used a photographic study preserved in the Tanner papers in which Jessie and the couple’s young son pose as the Madonna and Child (fig. 6) in the creation of Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures (c. 1910) and Christ Learning to Read (1910–14). While Jesus is often portrayed as teaching and imparting wisdom, Tanner chose not only to underscore his personal connection to this series of paintings by employing his wife and child as models but also invested Mary with the responsibility and wisdom to educate Christ, inverting his usual role. The photographic study captures a tender image of Jessie as she sits and embraces her son. The young Jesse leans affectionally into his mother, and with mirrored downcast glances, Jessie guides him through the words on the scroll. The pair are bonded through the transfer of knowledge and the collective acts of listening, seeing, and learning.

By painting over the figure of Lazarus in the Carnegie canvas, Tanner similarly grants the sisters a more direct bond with Christ as they listened and learned. The work’s alternative title, Christ at the Home of Martha and Mary, reinforces the absence of Lazarus by elevating the sisters as the primary characters of the biblical lesson. Considering the socially progressive Belle Époque circles that Henry and Jessie inhabited in France and these recurrent compositional and iconographic experiments, I believe the choices the artist made in the Carnegie canvas reveal his advocacy for women’s access to education and professional opportunities during the turn of the century, a major goal of first-wave feminism.20 In other words, Tanner’s decision to paint over Lazarus could be interpreted as an invitation to his audience to contemplate the gendered roles portrayed by Lazarus, Martha, and Mary in this biblical episode and consider the larger societal questions concerning the position of women and their intellectual capacities.

Dewey Mosby suggests that Tanner’s heightened sensitivity to the feminist movement was awakened during a 1901 trip to England when Henry and Jessie visited the home of Catherine Impey. Impey was a well-known feminist, temperance agitator, anti-segregationist, humanitarian worker, and the founder of the Anti-Caste, a publication that fought against discrimination and segregation. The couple’s time with Impey certainly would have included conversation on contemporary issues of race and gender discrimination, illuminating the intersectionality of these oppressions and potentially crystalizing Tanner’s investment in the representation of women over the next decade.21

Tanner’s understanding of the complexity of intersectional oppression and how to best advance both gender and racial equality led to a modification in how he chose to represent this biblical narrative over different iterations throughout the next decade. In the undated and 1912 versions of Christ at the Home of Lazarus (see figs. 2 and 3), Tanner returns to this religious episode but changes the orientation of the composition and adds the figure of Lazarus to accompany Christ and Mary at a table that expands horizontally through the middle of the canvas. In all three versions of this Gospel story, Tanner cast Jessie in the role of Martha. The later canvases depict a very different Martha from the one exchanging a distressed and tense glance with Jesus in the Carnegie version. In the later paintings, Martha sweeps into the composition from the left, attentively balancing a platter, which she eagerly presents to Christ. In the undated canvas, Jessie’s image is complemented by the figures of Mary and Lazarus, who are modeled by Tanner’s friends and benefactors, Ingeborg and Atherton Curtis.22

In March 2017, as I was studying the works by Tanner in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Luce Foundation Center, I was confronted by what I regrettably believe to be the remains of the original painting, now preserved in the Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Curtis with Still Life (fig. 7).23 Like many painters, Tanner was known to have reused or reworked canvases throughout his career.24 When compared with a photograph of this lost canvas—a document that is among the many valuable images included in the AAA’s Tanner papers—the relative dimensions, comportment of the figures of Ingeborg and Atherton, and the bowl of fruit on the table correspond with that of the study print preserved in the photograph (see fig. 2). According to this image, it appears that the canvas was cut to focus on the images of Ingeborg and Atherton for the Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Curtis with Still Life, transforming the remains of Christ at the Home of Lazarus into a secular portrait.

In the 1912 version of Christ at the Home of Lazarus (see fig. 3), Tanner uses his own image to embody the figure of Lazarus, taking the position of Atherton Curtis in the altered portrait. Although impossible to definitively determine based on the archival images alone, given Jessie’s appearance as both sisters in the Carnegie canvas, it is tempting to recognize her as the model for Martha and Mary in this version of the scene; here her presence would serve as a pendant to Tanner’s self-representation as Lazarus. Like the undated version, the location of this canvas is also unknown, but Clara MacChesney, an artist and journalist for International Studio, provides a description of the painting when it was first exhibited at the 1912 Paris Salon:

Tanner continues to be the poet-painter of Palestine. . . . His large Salon picture shows Christ at supper in the home of Lazarus. Martha standing and in the act of serving at the left. Christ is seated at the center, a self-portrait of the artist is represented at the right with Mary at his side. In the figure of Martha Tanner tries to raise her from the position of a worried housekeeper to that of a human and very sympathetic woman, lovingly serving her master. He considers this one of his most successful figures.25

MacChesney’s description of Martha is perceptive in identifying Tanner’s desire to portray her not simply as a foil to her sister Mary nor as the ideal patriarchal model of woman as attentive and subservient. Instead, as the journalist notes, the artist “raised” Martha’s position, rendering her as more than a servant making her an active participant in the composition, with a humanity and substance equal to that of her siblings seated with Christ. She serves them not out of spite but, as MacChesney recognizes, with “sympathy” and “love.” Here, Tanner’s representation of this narrative once again diverges from the Gospel text, which describes Jesus correcting the assiduous and anxious Martha for criticizing Mary’s desire to learn instead of to serve, stating, “Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her.”26

While the Gospel ultimately elevates spiritual and intellectual pursuits over industriousness, rather than disparage Martha, Tanner emphasizes her contributions as well. Unlike the earlier canvas, Christ at the Home of Martha and Mary (see fig. 1), which situates the figures of Jesus and Martha across from each other, sharing an uneasy and even confrontational gaze, in the 1912 version, the viewer only sees Martha from the back and side, correcting and potentially reversing any of the sternness or disappointment she is described as expressing in the Gospel text and in the earlier composition. I interpret Tanner’s desire to portray Martha actively and attentively serving her siblings and their holy guest with “sympathy” and “love” as an acknowledgment and appreciation of his wife, granting visibility to the ways she labored to nurture the intellectual, creative, and spiritual aspects of their home.

The two versions of Christ at the Home of Lazarus exemplify Tanner’s evolving approach to advancing women’s parity. While the Carnegie canvas attempts to elevate Martha and Mary by painting over Lazarus, Tanner came to recognize that gender equality for women could not be achieved by erasing men, rather by representing women in equal light with equal opportunities and choices. Although speculative, it is appealing to frame Tanner’s subsequent revisualizations of this biblical lesson as his attempt to provide a balanced table and a home where all were invited to contribute their own talents. In these later canvases, Martha serves out of love, and Mary sits with her brother and learns from Christ; both acts are necessary, valuable, and spiritually satisfying.

Tanner’s investment in these biblical sisters recognizes the industriousness and intellectual equality of women, something that he witnessed not only through the accomplishments of his mother, sisters, and nieces but is also demonstrated in Jessie’s own talents, intelligence, and skills as a musician, hostess, and homemaker. By underscoring Martha and Mary’s complexity and contributions, Tanner acknowledges and elevates the diverse and multifarious aspects of his partnership with Jessie.

My ongoing research on Tanner aims to demonstrate how the artist’s work set out not just to dismantle racial inequity and the white/Other binary but to envision a utopian, cosmopolitan existence where gender democracy was also possible. His decision to include women with active agency in biblical imagery, which was historically dominated by representations of men, visualized his principles and communicated the equality and unity offered through Christ’s teachings, a mission that was both inspired and sustained by his partnership with Jessie.

The remarkable women in Tanner’s life were models for the spiritual, cultural, and scholarly vitality that shaped the artist’s investment in the representation of women and how to best advance gender parity. Their exceptional lives, achievements, and contributions to his oeuvre deserve to be recognized. In reflecting on Jessie’s “Come to me” telegram, I have come to appreciate Tanner’s biblical images as not only visual manifestations of struggle and attempts to overcome hardship but also as representations of gratefulness, belonging, and love that were inspired by Jessie’s role in his life. In the coastal community of Trépied, France, the Tanners successfully created a home and community and were no longer “strangers in a strange land.” Jessie Tanner did more than simply support her husband’s artistic career. She was an integral and active collaborator in Tanner’s early twentieth-century biblical imagery, a partner of “equal talents” whose many roles the artist attempted to immortalize in this work through a celebration of biblical women.

Cite this article: Laura M. Winn, “A Collaborative Creation of Home: Recognizing the Multifarious Roles and Representations of Jessie Tanner,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18389.

Notes

I am grateful to Emily Burns, Katelyn Crawford, Elizabeth McGoey, and Oliver O’Donnell for their time and valuable feedback, which has significantly helped to clarify and shape this text.

- On gender relations and women’s roles in Belle Époque France, see James McMillan, France and Women, 1789–1914: Gender, Society and Politics (New York: Routledge, 2000); Susan Foley, Women in France Since 1789 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). ↵

- Dewey Mosby suggests that the figure who was painted over was Judas instead of Lazarus. Mosby believes the artist attempted to combine two Gospel narratives, which are held to have taken place in the same household, into a single painting: Jesus reproving Martha for criticizing Mary for not helping her serve (Luke 10:38–42) and Mary Magdalen anointing Jesus’s feet with expensive oils despite Judas’s believing she should have given the money to the poor (John 12:1–8). See Dewey Mosby, Across Continents and Cultures: The Art and Life of Henry Ossawa Tanner (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1995), 190. ↵

- Key scholarship on Henry Ossawa Tanner from the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries includes Dewey Mosby, Darrel Sewell, and Rae Alexander-Minter, eds., Henry Ossawa Tanner (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1991); Jennifer Harper, “The Early Religious Paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Study of the Influences of Church, Family, and Era,” American Art 6, no. 4 (Autumn 1992): 68–85; Mosby, Across Continents and Cultures; Sharon Patton, African-American Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Marcus Bruce, Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Spiritual Biography (New York: Crossroad, 2002); Richard Powell, Black Art: A Cultural History (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002); Kirsten Pai Buick, “Identity, Tautology, and the Death of Cleopatra,” in Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 133–207; Kristin Schwain, “A School-Master to Lead Men to Christ,” in Signs of Grace: Religion and American Art in the Gilded Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008), 42–70; Anna O. Marley, ed., Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); Naurice Frank Woods Jr. and George Dimock, “Affirming Blackness: A Rebuttal to Will South’s ‘A Missing Question Mark꞉ The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner,’” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 2 (Autumn 2010): 143–46, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn10/a-rebuttal-to-will-souths-qa-missing-question-mark-the-unknown-henry-ossawa-tannerq; Naurice Frank Woods Jr., “Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Negotiation of Race and Art: Challenging “The Unknown Tanner,” Journal of Black Studies 42, no. 6 (2011): 887–905; Naurice Frank Woods Jr., “Embarking on a New Covenant: Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Spiritual Crisis of 1896,” American Art 27, no. 1 (2013): 94–103; Naurice Frank Woods Jr., Henry Ossawa Tanner: Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy (London: Taylor and Francis, 2018). ↵

- Alan C. Braddock, “Painting the World’s Christ: Tanner, Hybridity, and the Blood of the Holy Land,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 2 (Autumn 2004): 12. http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn04/298-painting-the-worlds-christ-tanner-hybridity-and-the-blood-of-the-holy-land. ↵

- In Across Continents and Cultures, Mosby discusses how Henry met and married Jessie and that the couple spoke with Catherine Impey in 1901, but he does not make a connection between these events and the artist’s new interest in the representation of women (44–57). The artist’s investment in representing women has yet to be fully explored, with the exception of Michael Leja’s essay about Tanner’s series in the Ladies’ Home Journal, in “Reproduction Troubles: Tanner’s ‘Mothers of the Bible’ for the Ladies’ Home Journal,” in Marley, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 147–56. ↵

- Henry Ossawa Tanner papers, 1860s–1978, bulk 1890–1937, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter Tanner papers), https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/henry-ossawa-tanner-papers-9229; Laura M. Winn, “The Art of Becoming: Mimicry, Ambivalence, and Orientalism in the Work of Henry Ossawa Tanner and Hilda Rix” (PhD diss., University of Florida, 2018), https://ufl-flvc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01FALSC_UFL/175ga98/alma990368979580306597. ↵

- Telegram from Jessie Olssen to Henry Tanner in Jerusalem, February 25, 1899, box 1, folder 17 (Tanner, Jessie Olssen, 1899, 1918, 1925, “Correspondence”), Tanner papers, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/henry-ossawa-tanner-papers-9229/series-2/box-1-folder-17. ↵

- The Tanner women achieved myriad professional and academic milestones. Henry’s mother, Sarah Miller Tanner, organized the Mite Missionary Society for the AME Church, which was the first of its kind for African American women. Sarah and her daughters were active members in the Pierian Club, which advocated for and supported women’s intellectual pursuits. In 1895, Sarah published two articles: “A Study of Thoreau,” AME Church Review 11 (January 1895): 383–87, which contextualized the Transcendentalist’s writings within the sociopolitical life of early nineteenth-century New England, and “Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,” AME Church Review 12 (October 1895): 283–90. Henry’s sister Halle graduated from the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia and became the first woman of any race to pass the medical boards and practice in Alabama. Halle relocated to Alabama at the invitation of Booker T. Washington, who offered her a position as the resident physician at the Tuskegee Institute. Tanner’s niece Sadie earned a PhD in economics from the University of Pennsylvania and later became the first Black woman to graduate from Penn’s Law School, pass the bar, and practice in the state of Pennsylvania. See Rae Alexander-Minter, “The Tanner Family: A Grandniece’s Chronicle,” in Mosby and Sewell, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 23–33. ↵

- Henry O. Tanner, “The Story of An Artist’s Life, Part II,” World’s Work 18 (June 1909): 11770. ↵

- Most scholars agree that Henry and Jessie met in Barbizon; however, Mosby suggests that they met while Henry was painting landscapes in Cernay-la-Ville, northwest of the Fontainebleau Forest (Continents and Cultures, 46). ↵

- Marcia Mathews, Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 94. ↵

- Mathews, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 94. There are differing perspectives on Tanner’s life and work from his relatives on opposing sides of the Atlantic. Rae Alexander-Minter voiced her dissatisfaction with Mathews’s account of Tanner’s family history, specifically regarding his mother, Sarah Miller, and her enslaved origins, explaining: “Mathews, whose book Henry Ossawa Tanner was published in 1969, talked only briefly with my mother {Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander} and never on this issue. Mathews gained much of her information from Henry Tanner’s son, Jesse, who had lived his entire life in Europe. . . . He had a skewed view of America and particularly of race relations in this country. Certainly the story as told by Mathews is more comforting than the one told by mother, which shows how slavery tore at the fabric of the black family” (“Tanner Family,” 291). ↵

- Mathews, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 94. ↵

- Jean-Claude Lesage, “Tanner, the Pillar of Trépied,” trans. Jane Boyd, in Marley, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 88. ↵

- Helen Cole, “Henry O. Tanner, Painter,” Brush and Pencil 6, no. 3 (June 1900): 97–107. ↵

- Locals of the village, including Myron Barlow’s frequent model Louise Grandidier, joyfully recalled the summers when Henry would bike into Étaples from Trépied on a tricycle, towing Jessie in a little wagon. Lesage, “Tanner, the Pillar of Trépied,” 88 and n. 7. ↵

- Identifiable images of Jessie appear in many of Tanner’s works: The Artist’s Wife (c. 1898; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC), La Saint Marie (c. 1898; La Salle University Art Museum, Philadelphia), Music (1902, painted over with The Pilgrims of Emmaus, now in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris), figures from the Mothers of the Bible series (1900–1903; reproduced in the Ladies’ Home Journal), The Visitation (Mary Visiting Elizabeth) (c. 1909; Kalamazoo Institute of the Arts), The Three Marys (1910; Fisk University Galleries, Nashville, TN), Christ at the Home of Lazarus (multiple versions, but the only surviving canvas in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, c. 1905), Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures (1909; Dallas Museum of Art), and Christ Learning to Read (c. 1911; Des Moines Art Center). ↵

- “As Jesus and his disciples were on their way, he came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to him. She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet listening to what he said. But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to him and asked, ‘Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!’ ‘Martha, Martha,’ the Lord answered, ‘you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her.’” New International Version, Luke 10:38–42. ↵

- In addition to images representing the Virgin Mary teaching a young Jesus in Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures (c. 1910, Dallas Museum of Art) and Christ Learning to Read (1910–14, Des Moines Art Center), I propose that Tanner’s multiple interpretations of Christ walking on the Sea of Galilee include the representation of female followers in the fishing boat. The addition of female figures to this biblical narrative, which was traditionally portrayed by an all-male cast of characters, occurs several times but is most obvious in the etching The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water (1910 restrike; Philadelphia Museum of Art). Tanner portrayed nine apostles in an Étaplean style fishing boat. Separated from the primary figure of Peter, the other eight disciples occupy the hull or sit in the stern of the vessel. Several of these figures are rendered with beards or turbans, indicating their gender as the more traditionally represented male followers of Jesus. However, at the apex of the stern, Tanner arranged a group of three figures. Two of them are identifiable as men, but the third lacks facial hair and is veiled in the convention of Marian imagery, suggesting that the figure is a woman. The veiled head of this female follower of Christ is placed parallel with that of Peter at the front of the boat, formally suggesting a connection between the two, or their equal importance. Additionally, see The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water (c. 1907; Des Moines Art Center) and The Miraculous Haul of Fishes (c. 1913-1914, National Academy of Design). Winn, “The Art of Becoming,” 140–46. ↵

- Although Tanner claimed he never had official pupils, his contributions to the artist colony of Étaples make clear that he served as a mentor to many young artists. I have previously explored Henry Tanner’s role as a teacher and mentor to the artist Hilda Rix. Henry and Jessie volunteered to chaperone the young Australian artist, facilitating her first artistic expedition to Morocco in 1912. The diverse races, nationalities, and genders of the artists who learned from Tanner suggest his belief in equal access to educational and cultural opportunities. Between 1890 and 1937, aspiring Black artists traveled to Paris and Trépied to study with Tanner. These included Annie E. A. Walker, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (whom he once forgot to pick up at the train station), William A. Harper, and William Edouard Scott. When Scott suffered financial troubles while in France, Tanner invited him to stay at his home in Étaples, and under his tutelage, Scott was successful in showing three paintings at the Salon des Beaux Arts at Touquet in 1911. See Winn, “Art of Becoming”; Theresa Leininger-Miller, New Negro Artists in Paris: African American Painters and Sculptors in the City of Light, 1922–1932 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 2. ↵

- See Mosby, Across Continents and Cultures, 50; Mosby, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 152. Given the struggles and historical achievements of the women in the Tanner family, it is reasonable to believe that Tanner’s 1901 meeting with Impey did not introduce him to the concept and complexity of intersectional gender and racial discrimination; it is more likely that this meeting crystalized the artist’s commitment to social justice. This understanding is expressed by Tanner’s father, Reverend Benjamin Tanner, in a letter he wrote to Booker T. Washington, in which Reverend Tanner voices concerns for his daughter’s success in Alabama, demonstrating an awareness of the multilayered oppression Halle Tanner faced as a Black woman attempting to enter the professional medical field: “Of course, we are all anxious about the Doctor. Not that we have any misgivings as to her ability to pass any reasonable and just examination. But we know that both her sex and her color will be against her.” Quoted in Alexander-Minter, “Tanner Family,” 29. ↵

- Mathews, Henry Ossawa Tanner, 90–91. ↵

- I would like to thank Luce Curatorial Fellow Jill Vaum Rothschild and Luce Foundation Center Program Coordinator Bridget Callhan for their time and efforts in helping to confirm that the Curtis portrait held in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection can be connected with the now-lost version of Christ at the Home of Lazarus, which included the figures of Atherton and Ingeborg Curtis. The curatorial file “Henry Ossawa Tanner: Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Atherton Curtis with Still Life, 1983.95.192” describes findings from examination by conservation fellow Barbara Wojcik in 1994: “The radiography of the Curtis portrait provides the connections to the AAA photograph Christ at the Home of Lazarus. The radiograph reveals that underneath the Curtis portrait is a figure group with an oriental screen to the left identical to that in Christ at the Home of Lazarus. The Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Atherton Curtis with Still Life appears to have once been the larger composition seen in the Juley photograph which appears to have been a reworked version of Christ at the Home of Lazarus. . . . It is evident that Tanner reworked the painting entitled Christ at the Home of Lazarus extensively. The severe traction/mechanical cracks are then explained. The remaining question is whether the painting was cut down by Tanner during another attempt to rework the painting, or whether a restorer cut down the painting. . . . {I}t is my opinion that Tanner did not cut down the canvas.” Based on her research, Wojcik believes that the canvas was left in Tanner’s studio until his death in 1937 and was subsequently cut and remounted to sell the work as part of the artist’s estate in the 1960s. ↵

- There is a study for the 1912 version of Christ at the Home of Lazarus painted on the back of the Flight Into Egypt (c. 1923; Metropolitan Museum of Art). Examples in which Tanner has painted over existing compositions include The Pilgrims of Emmaus, which obscures La Musique, a canvas that featured Jessie and her sister at the piano. More recently, Jeffrey Richmond-Moll discovered a lost painting of Judas, which is now Two Disciples at the Tomb (The Kneeling Disciple) (c. 1925, Art Institute of Chicago) (“Henry Tanner’s Judas: The Lost Disciple,” Smithsonian Archives of American Art, By the Archives, November 7, 2018, https://www.aaa.si.edu/blog/2018/11/henry-tanners-judas-the-lost-disciple. ↵

- Clara MacChesney, “American Artists in Paris,” International Studio 54 (November 1914): 27. ↵

- Luke 10:41. ↵

About the Author(s): Laura M. Winn is an Assistant Professor of Art History in Jacksonville University’s Stein College of Fine Arts and Humanities.