“A Harmony in Eggs and Milk”: Gustatory Synesthesia in the Reception of Whistler’s Art

Just think fifty [pastels]—complete beauties!—and something so

new in Art that every body’s mouth will I feel pretty soon water—

—James McNeill Whistler to Helen Euphrosyne Whistler, 18801

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) pursued a zealous campaign to attain recognition for the exclusively visual qualities of art from British viewers accustomed to seeking moral lessons or anecdotal diversion in paintings. Many Victorian critics, however, judged the expatriate American artist to be an opportunistic showman who sought to inflate the value of his art through a variety of publicity maneuvers.2 Among Whistler’s challenges to conventional modes of viewing were the musical titles he gave his works, such as symphony, arrangement, harmony, and nocturne. To liken painting to music was a nineteenth-century device to emphasize the significance of the abstract formal qualities of a painting over its subject matter.3

While existing studies have explored links between Whistler’s art and music, this essay instead identifies and traces a recurring strain of gustatory metaphors in the reception of Whistler’s art that parodied his musical titles by likening his visual productions to food and drink. Through their humor, these gastronomic analogies imply a critique of the artist’s synesthetic titling of his paintings, as sardonically articulated by one critic in 1877: “if music may be called on to assist painting by the aid of its nomenclature, then practically endless fields are opened up. . . . For if music may be made tributary to painting, why not rhetoric, cookery, and perfumery as well?”4 While critics deployed culinary references most apparently to mock the perceived pretension of Whistler’s musical titles, such parodic food imagery further resonated with serious questions about pictorial significance and aesthetic experience that Whistler’s art and its formalist aims stimulated. Food parodies, like musical metaphors, spoke to the powerful effects of nonverbal sensuous experience, thereby providing terms of reference for paintings that eschewed narrative, prioritized the expressive capacity of color itself, and approached abstraction. In contrast to the high cultural connotations of Whistler’s musical titles, however, his critics’ gustatory analogies situated the viewer’s consumption of the abstract qualities of art within the material domain of animalistic bodily impulses and gratification, implying references to unruly and unseemly physical appetites. The humor of these gustatory references depended on tacit complicity with a longstanding hierarchy of the senses in Western culture since Plato and Aristotle, which privileged sight and hearing as “higher” senses positioned above the “lower” senses of touch, smell, and taste.5

The association of Whistler’s art with comestibles in the popular press developed in the 1870s as critics responded to the deliberate strangeness of his paintings and their titles, which synesthetically conflated aural and optical realms by commingling musical and color terminology. When Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother (1871; Musée d’Orsay) was exhibited in 1872, the Daily Telegraph reacted to the stark composition and restricted palette of the painting by likening it to a thin and poisonous soup of “Warren’s blacking, diluted with skimmed milk.”6 Six years later, when Variations in Flesh Colour and Green: The Balcony (1864–70; fig. 1) was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, a reviewer in Punch commented, “From this description an uninitiated person might expect a picture of ‘Bacon and Spinach’ or ‘Ham and Peas’”; later in this satirical piece, the critic demands a “symphony in Something and Seltzer” to drink at the gallery’s restaurant, presumably to settle his stomach from the effects of Whistler’s art.7 Whereas “Bacon and Spinach” and “Ham and Peas” respond to the colors named in the painting’s title without echoing its distinctive structure of a musical term “in” two colors, many other gustatory spoofs of Whistler’s art parodied his synesthetic titles, substituting for the artist’s combination of music and color instead music and food. So, for example, a review of the Dudley Gallery exhibition in 1873 referred to the influence of “Whistler’s symphonies in jam and pomatum, nocturnes in pease-pudding and carraways, variations in what you will.”8 While “pease-pudding and carraways” evokes the perceived formlessness of the Nocturnes through the image of a common pudding of mushy peas, “jam and pomatum”—like the earlier “Warren’s blacking, diluted with skimmed milk”—combines an edible substance with a manufactured product—hair pomade—in a nauseating or toxic compound. Moreover, while the combined textures of gelatinous jam and oily pomade might indeed produce a viscous substance that could be brushed on a canvas, the pomatum further suggests association with Whistler’s well-known dandyism and distinctive coiffure,9 while the jam may allude to the initials of the artist’s full name: J. A. M. Whistler.

In the 1880s, the gastronomic parodies that appeared in the press often reacted to Whistler’s new exhibition designs, which were noted both for the spacious hanging of the works and for the striking repetition of a few key colors in all details of the gallery interior and furnishings. For solo exhibitions in this decade, the artist not only entitled his curated group of works as a whole but also designated his interior decoration of the gallery for each exhibition as a work of art in itself, an “arrangement” in color. The exhibition design for Mr. Whistler’s Etchings at the Fine Art Society in 1883 was entitled Arrangement in White & Yellow; the installation of “Notes”—”Harmonies”—”Nocturnes” at Dowdeswell’s Gallery in 1884 was named as Arrangement in Flesh Colour & Grey; while the installation of “Notes”—”Harmonies”—”Nocturnes” (second series) at Dowdeswell’s in 1886 was Arrangement in Brown & Gold.10 Whistler’s musical title “Arrangement” named each exhibition installation as a harmonious work of art, implying parallels between the installation’s prevailing colors and the key of a musical piece. The Arrangement in White and Yellow etchings exhibition of 1883 attracted particular critical notice, including recurrent gustatory analogies: one critic described the “glare of yellow” as “very irritating to the optic nerves” and likened the public’s experience of entering the gallery to having “cayenne pepper” thrown into its eyes,11 even while other published accounts of the exhibition referred to the gallery attendant in yellow-and-white livery as the “poached egg.”12 A rhyme that appeared in Punch about the exhibition took the form of an imagined dialogue between Whistler and the critic Harry Quilter:

Says JIMMY to ‘ARRY, “You do a lot of scrawls,

And frame them very carefully, and stick them on buff walls,

You deck the place with saffron silk,

And pots the hue of mustard,

A harmony in eggs and milk—”

Says ‘ARRY, “Like a custard!”13

Just as Whistler’s 1883 exhibition had included the so-called poached egg clad in white-and-yellow apparel as a living component of the installation, so too the artist’s Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Grey installation of 1884 featured an attendant in a flesh-color-and-gray outfit, described in one periodical as “a new liver-and-bacon suit of livery.”14 Another published piece referred to the 1884 exhibition as Whistler’s “indigestion in crushed strawberry and verdigris.”15

The implications of these culinary parodies varied in scope: most often, the food and drink analogies responded to the dominant colors of Whistler’s work, following the lead of the actual title of the work that combined a musical term with chromatic elements. A more properly synesthetic type of comparison was based less on color parallels than on the distinctive quality of a food or beverage corresponding to the properties of the art, such as the bubbliness of seltzer evoking the perceived emptiness and frivolity of Whistler’s art, or the sting of cayenne pepper expressing the optical assault of his white-and-yellow gallery decoration. Another writer’s response to Whistler’s Arrangement in White and Yellow installation strikingly combined references to physiological optics and to an edible condiment in order to convey the somatic shock of beholding of this intensely colored interior: “The eye is soon dazed and wearied with the glare of yellow and white; the optic nerve is, in fact, stung as with mustard.”16 Indeed the favored comestible trope in Punch for Whistler’s art was mustard17—a substance that is smeared on bread in an activity not unlike brushing paint on a canvas. The mustard analogy speaks to Whistler’s art in several ways: first, to the color yellow, for the pronounced use of which Whistler was known;18 and second, to the pungency of his defiantly unconventional art, as well as to the sharp, cutting quality of his widely publicized words and persona. Furthermore, mustard taken in quantity functions as an emetic, so this metaphor could suggest that Whistler’s art would generate ill health or physical revulsion in his viewers.

Such implications that Whistler’s art would have unhealthy effects on its viewers respond to the incipient abstraction of his art in the context of debates in Victorian Britain about the nature of aesthetic experience, particularly those addressing how aesthetic perception involves the body and the mind.19 In prioritizing color and other abstract elements of painting, Whistler opened the door to accusations that his art was nothing more than “mere” decoration, providing the viewer with a sensuous experience lacking moral or intellectual significance. For not all Victorian viewers would concur with Walter Pater’s contention that aesthetic experience combines sensory perception with intellectual faculties through what he called the “imaginative reason.”20 While Pater’s famous reference to music as exemplifying the condition toward which all the arts aspire links visual art with the dematerialized intangibility of music,21 the gastronomic spoofs of Whistler’s art instead associate this art with the materiality of food and drink to be consumed by an emphatically embodied viewer.22

As Victorian art critics discussing the unstable position of the aesthetic between sensuous and intellectual domains themselves noted, the fact that another term for aesthetic judgment is “taste” in itself signals a continuity between aesthetics and eating. For John Ruskin, an approach to art that focused on taste was problematic, even immoral, not only in privileging classed standards of judgment inculcated through elite education, but also in prioritizing style over substance and truth. In Modern Painters, Ruskin wrote: “the name which is given to the feeling,—Taste, Goût, Gusto,—in all languages indicates the baseness of it, for it implies that art gives only a kind of pleasure analogous to that derived from eating by the palate.”23 If for Ruskin the association of aesthetic experience was degraded by what he viewed as the “baseness” of gustatory delectation, the critic Philip Gilbert Hamerton did not view connections between eating and artistic aesthesis as discrediting the aesthetic. Instead, when Hamerton described the transformation of animal sensation through “a process of gradual elevation and refinement” into aesthetic perception in his article “Notes on Aesthetics,” he supported his assertion with reference to how “the pleasures of the table” can attain “the domain of the higher aesthesis.”24 For Hamerton, the multiple connotations of taste served to confirm the validity of gustatory aesthetics: “Only the most ignorant criticism would deny that, in quite a serious and artistic sense, there is an aesthetic element in the pleasures of eating and drinking. . . . The very use of the word ‘taste’ in art-criticism is a clear recognition of the analogy between aesthetic perception and the sensations of the palate.”25

In the year preceding the publication of Hamerton’s “Notes on Aesthetics,” the widely publicized Whistler-Ruskin trial of November 1878 had drawn public attention to debates about the merits of painting that based its value and significance on its aesthetic properties—most notably, its manipulation of color. The painting that occasioned Ruskin’s critique, which prompted Whistler to sue the critic for libel, is well known today for its central role in the trial. Whistler entitled the work, in his signature fashion, as Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875; fig. 2): the first part of the title likens the work to a musical nocturne, such as the piano compositions of Frédéric Chopin, and names the color key of black and gold in lieu of a musical reference to a major or minor key. The second half of the title specifies a mimetic referent, in this case exploding fireworks. By positioning the musical component first in his title, Whistler signaled his concern to grant priority to the formal qualities of the painting, followed only secondarily by its representational subject matter. And while Nocturne in Black and Gold does indicate shadowy figures in the gloom of a night scene dominated by a display of fireworks, the painting may first strike the viewer as an animated scattering of dots, flecks, and patches of yellow pigment accenting a dark field layered with veils of paler gray paint. While spatial coordinates are obscured and figures only sketchily adumbrated, the texture of oil paint—varying from densely smeared to thinly scumbled on the wood support—and the range of colors—blacks modulated by grays, and yellows tinged variably with white, green, red, and orange—carry autonomous expressive power.

Whistler’s celebrated Nocturne in Black and Gold exemplifies his anti-academic prioritization of color over line, and of the composition of colors over the depiction of mimetic detail. Such characteristics led critics to deem his paintings unfinished—mere sketches or daubs—and to rail against their perceived formlessness, as in Ruskin’s oft-quoted claim that Nocturne in Black and Gold was a “pot of paint” flung in the face of the public.26 Discomfort with Whistler’s reduction of linear definition—associated in nineteenth-century art theories with intellect, control, and masculinity—to prioritize instead color and the material properties of paint—associated with the senses, the body, excess, and femininity27—may lie behind the antic tone of the gastronomic spoofs of Whistler’s art. Moreover, precedent for mocking the coloristic formlessness of a painting by means of culinary analogies existed in the earlier reception of J. M. W. Turner’s art, which had also challenged viewers with effects of blurriness and visual indeterminacy. As early as 1827 and continuing through the 1840s, critics and other viewers had likened Turner’s paintings to a variety of foods, including curry, jam tarts, sugar candy jellies, pastry, eggs, and lobster salad.28

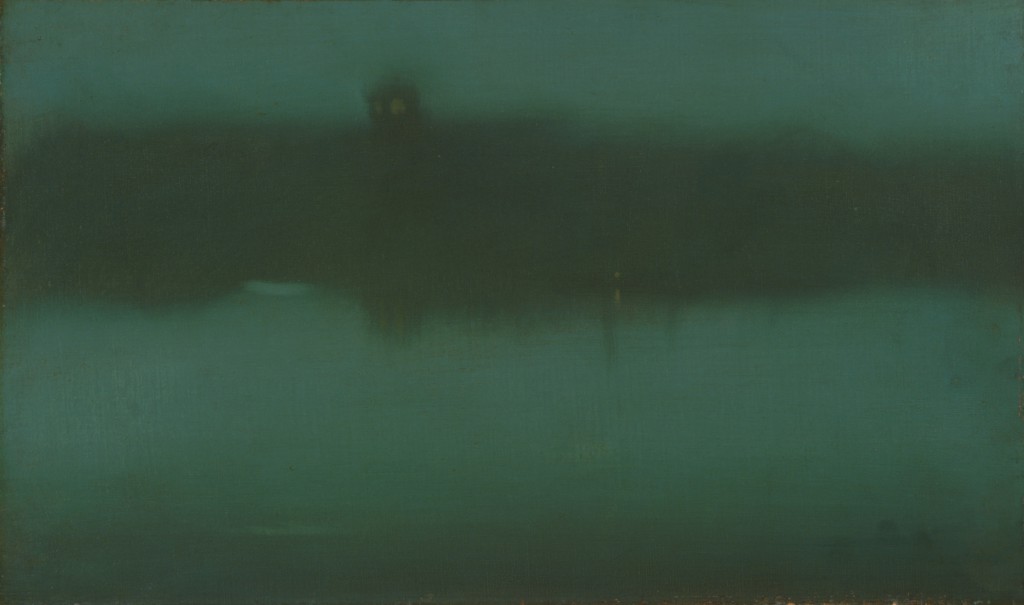

Critics’ disapproval of the coloristic amorphousness of Whistler’s Nocturnes informed their association of his art with food and drink. Many such references were to beverages, which in their liquid formlessness would correlate with the lack of linear clarity and the signs of the paint’s fluidity apparent in Whistler’s paintings. In his canvases after 1870, the artist thinned his paint with an exceptionally fluid medium, which he called his “sauce,”29 a term that metaphorically shifts his painting materials and technique from the studio to the kitchen. For example, Whistler’s Nocturne (1875–80; fig. 3) features paint so diluted by his “sauce” that the canvas appears almost to have been dyed or stained rather than painted, as only the most shadowy indications of buildings along the Thames at night dissolve into a horizontal expanse of dark gray suspended between two soft-edged fields of blue-green. Responding to this distinctive technique of extremely thin paint application, critics likened Whistler’s paintings to such varied beverages as milk, sack and sugar, and sake30—this fermented rice beverage alluding to the elements of Japonisme in Whistler’s paintings, as well as to the material presence of the liquid facture in compositions of pigmented oil thinned by his “sauce.”31 As both sack (or sherry) and sake are alcoholic drinks—one from Spain and the Canary Islands, the other from Japan—these references to intoxicating beverages not only indicate the increasing globalization of food and drink in nineteenth-century Britain but could also evoke the disorienting effects on the viewer of the near-abstraction of such paintings as this Nocturne, in which indeterminacy and blurriness resist clear focus and challenge spatial perception. Even comparisons to solid food could by implied extension of the analogy point toward formlessness, for no matter how ornamented and shaped by molds—then also called “shapes”32—much Victorian food might be, after its consumption, inside the stomach and intestines, all food takes on a condition of formlessness. And, of course, how and where food ends up after ingestion and digestion is in quite a different state and situation from the intellectual and emotional elevation associated with the aesthetic.

While the critical parodies of Whistler’s art as comestibles never directly referred to any bodily process as unseemly as excretion, the gastronomic spoofs often implied that his art was not merely unappetizing but difficult to digest, even nauseating. For example, a critic at Whistler’s 1883 exhibition described the unrelenting repetition of yellow and white as triggering “an attack of ocular dyspepsia” in viewers; this critic further referred to the “artistic biliousness” of Whistler’s decoration of the gallery space, thus evoking association both with aptly-hued yellow bile and with gastric distress.33 Such critical barbs as “ocular dyspepsia” would register sharply with a Victorian audience widely familiar with stomach complaints and inclined to focus on indigestion as the central health problem of the nineteenth century.34 Further metaphoric digestive troubles were reportedly induced in viewers of Harmony in Yellow and Gold, a drawing-room suite on display at the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Showcasing furnishings designed by E. W. Godwin and made by William Watt, Harmony in Yellow and Gold featured decorative motifs—butterflies, blossoms, and stylized cloud motifs—of gold on an intensely lemon-yellow ground painted by Whistler on the imposing central cabinet, as well as the dado and wall.35 A critic visiting the exhibition in Paris joked that those viewing this display would need receptacles at hand for their vomit, implicitly likening the visual experience of the “harmony” to a bumpy ride in a galloping stagecoach: “Whistler has done a harmony in yellow-and-gold . . . which turns bilious people green when they look upon it. The attendants in the section it is in have basins handy now, like the stewards on the mail packets.”36

Stomach distress as a metaphor for the effects of an artistic assault on viewers’ eyes could also be implied by critical parodies that likened Whistler’s art to disgusting combinations of foods. A squib in Punch in 1888, for instance, characterized his art as an unappetizing combination of licorice, tripe, and apple tart: as a fox and an ass admire a “nocturne in yellow and black” by Whistler, the fox exclaims, “‘Oh, what magnificent hues!’ . . . ‘look at that splash of pink liquorice, that daub of shot puce-vermilion tripe, that splutter of tawny-green-gamboge apple-tart!’”37 While the main thrust of this satirical piece is to make fun of Sir John Lubbock’s recently published study of perception in different animal species,38 the fox’s comments also suggest a trisensory synesthetic parody of Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (fig. 2)—the title’s second color demoted from shining gold to simply yellow—that commingles references to gustatory, auditory, and visual sensations: the “splutter” evoking both the explosive sound of fireworks and inarticulate confusion, the “splash” of licorice reminiscent both of Ruskin’s celebrated allusion to paint flinging and of spilled sauce in a kitchen, and the color “gamboge” referring to a resin used both as a yellow pigment in painting and as a medicinal cathartic to purge the bowels. That this synesthetic lampoon surfaces in a parody of Lubbock’s On the Senses, Instincts, and Intelligence of Animals, with Special Reference to Insects signals that culinary spoofs of Whistler’s art touched on questions about the relationship of aesthetics to human sensory capacities—placed in a continuum with perception in other animals after Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution—explored in contemporary scientific as well as artistic and philosophical studies.

The humor of the gustatory parodies of Whistler’s art for Victorian audiences depended on an assumption that food did not constitute a proper art form equivalent in cultural value to music, literature, and painting. Yet while critics used gustatory parodies to deflate what they saw as the pretensions to high art of paintings that abjured morality and intellect in favor of sensuous delectation, such interplay between food and fine art also carried the potential to undermine cultural hierarchies subtended by gender hierarchies. Analogies between food and painting could be employed in other fashions and contexts to elevate cooking to the status of an art, whether produced by French-trained male chefs at restaurants in grand hotels or by female domestic cooks in middle-class homes. While an analysis of the status of cooking as gendered cultural production in Victorian England lies beyond the scope of this essay, one noteworthy example of a growing respect for the culinary arts in late Victorian Britain can be found in Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s “cookery” column, published regularly in the Pall Mall Gazette from 1893 to 1896.39 Pennell, an art critic who was good friends with Whistler and coauthored his biography with her husband Joseph, included many effusive analogies between food and painting in her culinary essays, as in her instructions for preparing sole au gratin: “lay the sole upon this liquid couch; . . . bury it under bread-crumbs, and bake it until it rivals a Rembrandt in richness and splendor.”40 While nineteenth-century terminology broadly reveals that loose associations between the activities of painting and cooking were common—artists mixed paint from “recipes” and spoke of their material techniques as the “cuisine” of painting—Pennell’s culinary writings connect gastronomy and painting in a notably deliberate fashion. More specifically, phrases that echo Whistler’s synesthetic titles surface in Pennell’s cooking column, as when she describes poached eggs on a purée of mushrooms as “a harmony in soft dove-like greys and pale yellow” or calls bouillabaisse “A Symphony in Gold.”41

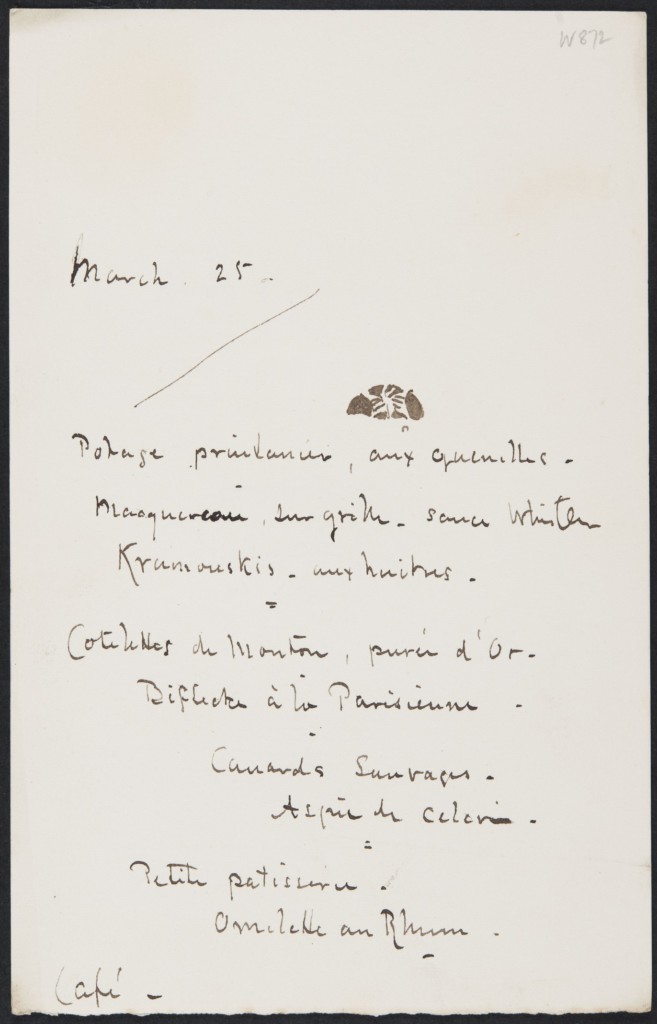

Attentive to the decorative as well as gustatory properties of food, Whistler encouraged the perception of correspondences between his cooking and his paintings, as when he offered green-tinted butter to harmonize visually with his blue-and-white porcelain.49 The porcelain plates on which the artist served and ate his meals constituted another link between aesthetics and eating: as one of the most avid collectors of Chinese porcelain in Britain in the 1860s, leading the way for what became the vogue of “Chinamania” in subsequent decades, Whistler had long asserted that porcelain plates, bowls, and cups were not only things from which to eat and drink but exemplary works of art.50 If for Whistler a blue-and-white plate was both useful and beautiful, so too were the gustatory compositions placed upon it. Another one of the artist’s handwritten menus in French names herrings as a “note rouge,” fish cakes “en harmonie,” and mutton cutlets with a “purée d’Or”—a golden purée, perhaps of carrots or turnips—to combine musical terminology with color references in a fashion that echoes the musical titles he gave his paintings.51 Thus, while Whistler’s detractors employed food parodies to denigrate his art, the artist suggested correspondences among colors, sounds, and flavors to promote the aesthetic value of both his formalist paintings and his fine cooking.

Whistler’s use of language to evoke synesthetic connections among the three sensory domains of seeing, tasting, and hearing occurs not only in the menus for his dinners but also in his titling of one painting from 1883 or 1884 as An Orange Note: Sweet Shop (fig. 5). This title’s punning allusions to the multiple connotations of “orange” and of “note” suggest an amalgamation of delicious color, sound, and taste in this oil on panel—the vivid color orange consorting with the imagined taste of the oranges in the shop window; the sweet sounds of musical notes conflated with the artist’s visual notation of morsels of color. An association of seeing with eating is further promoted by the strikingly small size of the painting: measuring less than five inches high and eight-and-a-half inches wide, this painting as a material object would easily fit on a dinner plate. To extend the metaphoric association of eating with visual consumption further, this diminutive painting could conceivably rest inside a viewer’s abdominal cavity. Whether processed literally by the viewer’s brain or metaphorically by their stomach, the painting registers the color of the citrus fruit in the window like a musical note that accents the warm gray harmony and is echoed by the red dress of the child held by a woman or girl in the doorway, the human expression of their faces blurred into obscurity to prioritize instead the colored patches of dress, pinafore, and apron. Shape, as well as color, contributes to the visual feast of the image, as the dark oblongs of window and doorway at left and right are balanced against each other on the shop’s façade, which runs not quite parallel to the picture plane, so that a delicate tension exists between pure planarity and deliberately shallow pictorial space. The curving edges of the foil that negatively defines the artist’s butterfly signature at the left echo the rounded shapes of the oranges, which provide a visual counterpoint to the geometric grid of the mullioned window, the horizontal row of vertical canisters of sweets above the fruit, and the square shape that suggests a box in the window’s lower corner. Whistler’s paint handling adds further richness to the visual delicacies of the painting, as the active play of visible brushstrokes animates the representation of the flat façade. In these ways, the elements of color, shape, composition, and facture come together in this work, which—through its assertively small scale that demands physically close viewing—seeks intimate connection with an embodied viewer who feels, thinks, sees, and tastes.

Although increasing numbers of art critics, collectors, and other viewers in the 1890s came to appreciate the optical succulence of Whistler’s art, writers still occasionally employed gustatory analogies to mock the artist and his art. An especially elaborate parody of Whistler’s art as gastronomy unfolds in a short text by H. G. Wells, published as “A Misunderstood Artist” in The Pall Mall Gazette in 1894, a time when Elizabeth Robins Pennell’s “Wares of Autolycus” column appeared regularly in the same publication. The central character in Wells’s tale is an “artist in cookery” who describes his gastronomic compositions in unmistakably Whistlerian terms: in one instance, “some curious arrangements in pork and strawberries, with a sauce containing beer . . . a beautiful Japanese thing, a quaint, queer, almost eerie dinner,” and in another, “some Nocturnes . . . with mushrooms, truffles, grilled meat, pickled walnuts, black pudding, French plums, porter—a dinner in soft velvety black.”52 Moreover, the artistic ambitions of the cook are clearly modeled on Whistler’s widely publicized aesthetic stance and artistic elitism. In terms that resonate with Whistler’s scorn for art preoccupied with “usefulness” and “virtue”53—an Aestheticist position philosophically rooted in Immanuel Kant’s distinction of the beautiful from the good—the cook declaims that cooking is “The noblest [art]. . . . But sorely misunderstood; degraded to utilitarian ends.” Key issues at play in analogies between food and art surface when the cook declares, “Our function is to make the beautiful gastronomic thing, not to pander to gluttony, not to be the Jesuits of hygiene.”54 For the three clauses of this sentence correspond to the three terms—the beautiful, the agreeable, and the good—that Kant distinguishes from one another in his analysis of aesthetic judgment.55 In the cook’s assertion, the “beautiful gastronomic thing” is opposed to food that would serve either the unthinking sensuous indulgence of gluttony, an excessive variant of Kant’s “agreeable,” or the improving purposes of hygiene and health, a version of Kant’s “good.”

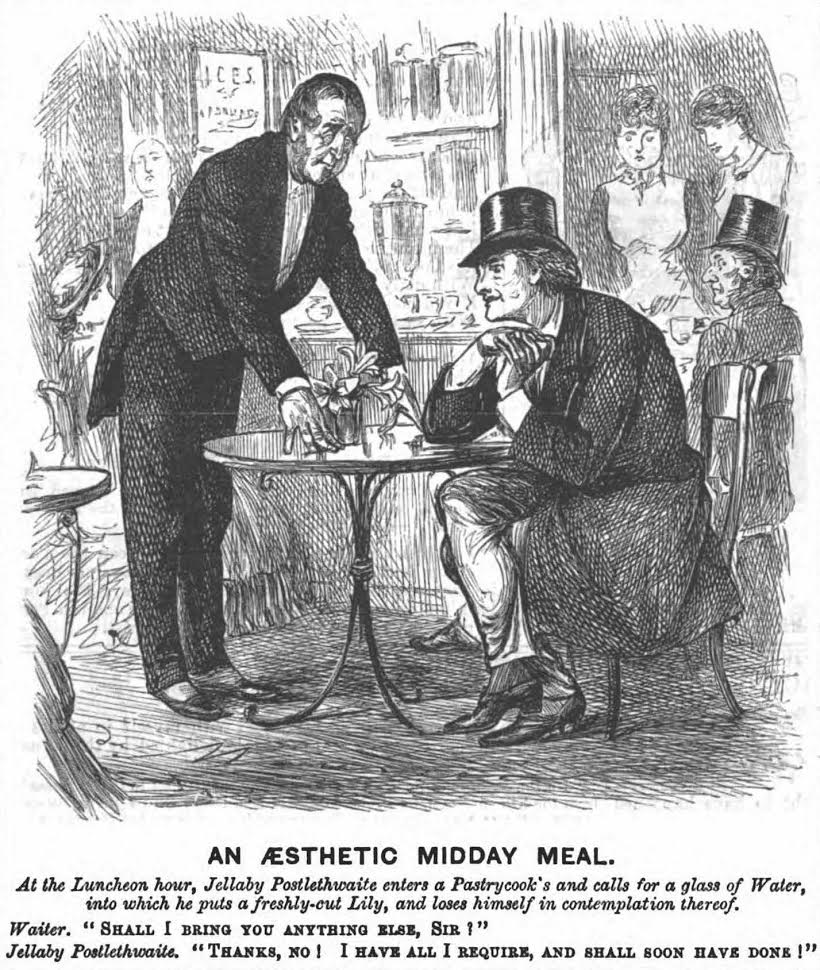

While this essay has focused on how gustatory parodies of Whistler’s art aimed to collapse the beautiful into the merely agreeable, we might further consider how such satirical play with gastronomy and gustation could complicate or blur distinctions between the beautiful and the useful or mediately good. We might, for example, consider the implications of George du Maurier’s Punch cartoon of 1880, An Aesthetic Midday Meal (fig. 6), in which the Aesthetic poet Jellaby Postlethwaite lunches by feasting his eyes on the blossoms of a lily. The seated poet bends toward the lily with his hands clasped as if in prayer: by conjoining this body language with the scenario of consuming a meal at a restaurant or pastry cook’s establishment, du Maurier’s cartoon represents the aesthetic experience of visual beauty as a funny hybrid of spiritual contemplation and eating lunch. While the poet’s incongruous behavior in the cartoon may amuse us as its viewers, du Maurier’s image—like Victorian critics’ gustatory spoofs of Whistler’s art—touches on significant aspects of Aestheticism, since a combination of the sensuous or bodily with the intellectual or spiritual is central to definitions of the aesthetic. With respect to distinctions between the beautiful and the useful, the cartoon also amuses because we know that a person cannot live on a diet of beauty—yet perhaps our engagement with the captioned image involves a further level of response, as a part of us may feel that in some way beauty is essential to sustain life. The categorizations of philosophy might give way, in our bemused attention to du Maurier’s image, to a less clearly defined mixture, for which no quantifiable recipe exists, of both being aware of the theorized uselessness and knowing the felt necessity of beauty.

Cite this article: Aileen Tsui, “‘A Harmony in Eggs and Milk’: Gustatory Synesthesia in the Reception of Whistler’s Art,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1607.

PDF: Tsui, A Harmony in Eggs and Milk

I would like to thank Guy Jordan and Shana Klein for their editorial comments and thoughtful suggestions.

- The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler, 1855–1903, Margaret F. MacDonald, Patricia de Montfort and Nigel Thorp, eds., online edition, University of Glasgow (http://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence). Whistler to Helen Euphrosyne Whistler (February 20/March 1880), University of Glasgow Library, Whistler Collection, Special Collections (hereafter, GUL) W684; University of Glasgow Library system number (hereafter, GUW) 06690 (accessed June 15, 2017). ↵

- For the reception of Whistler’s art, see Catherine Carter Goebel, “Arrangement in Black and White: The Making of a Whistler Legend,” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 1988). For representations of Whistler’s persona, particularly in the American press, see Sarah Burns, “Performing the Self,” in Inventing the Modern Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 221–46. The present article focuses on the reception of Whistler’s art chiefly in British periodicals. ↵

- Existing studies of Whistler’s painting locate the artist’s use of musical analogies in the context of Romantic and Symbolist privileging of music as a model for abstract art. See Suzanne Singletary, James McNeill Whistler and France: A Dialogue in Paint, Poetry, and Music (London: Routledge, 2016). ↵

- “Whistler: A Fantasia in Criticism,” London, August 18, 1877, 62. ↵

- See Carolyn Korsmeyer, Making Sense of Taste: Food and Philosophy (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999). Gender associations play a significant role in this hierarchy, linking the “higher” senses with masculinity and the “lower” senses with femininity. ↵

- “Exhibition of the Royal Academy,” Daily Telegraph, May 4, 1872, 5. ↵

- “Our Guide to the Grosvenor Gallery (First Visit),” Punch, June 22, 1878, 286. ↵

- “The Dudley Gallery—Seventh Annual Exhibition,” Building News and Engineering Journal 25 (November 28, 1873): 605. ↵

- For Whistler’s sessions at the hairdresser, see Mortimer Menpes, Whistler as I Knew Him (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1904), 33–35. ↵

- On Whistler’s exhibition designs, see Kenneth John Myers, Mr. Whistler’s Gallery: Pictures at an 1884 Exhibition (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2003). ↵

- Unidentified clipping in University of Glasgow Library, Whistler Press Cutting book 3:44; hereafter, GUL PC. Microfilmed by Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, reel 4687, frame 0216; hereafter, AAA. ↵

- London Weekly Register, February 24, 1883; Country Gentleman, 1883; The Pictorial World, March 31, 1883; as cited in “Mr. Whistler’s Galleries: Avant-garde in Victorian London,” Resource Library Magazine, 2003, http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/4aa/4aa170.htm (accessed May 26, 2017). ↵

- “Private and Confidential,” Punch, March 10, 1883, 110. ↵

- GUL PC 6:55 (AAA, 4687, 0553). ↵

- Clipping labeled as Society, May 17, 1884, GUL PC 8:7 (AAA, 4687, 0624). ↵

- “Mr. Whistler’s Fiasco,” GUL PC 6:46 (AAA, 4687, 0543). ↵

- See “Posters for Posterity,” Punch, April 30, 1881, 196; “An Arrangement in Condiments,” Punch, March 3, 1883, 102; and “‘Arry (With Tom and Dick) at the Grosvenor Gallery,” Punch, January 10, 1885, 24. ↵

- See Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties: A Review of Art and Ideas at the Close of the Nineteenth Century (London: G. Richards, 1922), 46–47. ↵

- See, for example, Judith Stoddart, “Pleasures Incarnate: Aesthetic Sentiment in the Nineteenth-Century Work of Art,” in Aesthetic Subjects, ed. Pamela R. Matthews and David McWhirter (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 70–98. ↵

- See Walter Pater, “The School of Giorgione” (1877), in The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry, 4th ed. (1893; repr., New York: Dover, 2005), 92: “the ideal examples of poetry and painting being those in which . . . form and matter, in their union or identity, present one single effect to the ‘imaginative reason,’ that complex faculty for which every thought and feeling is twin-born with its sensible analogue or symbol.” ↵

- Ibid., 90: “All art constantly aspires toward the condition of music {italics in original}.” ↵

- For nineteenth-century theories of embodied vision, see Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990). ↵

- John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 3 (1856), in The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, Library Edition, 39 vols. (London: George Allen, 1903–12), 5:96. ↵

- P. G. Hamerton, “Notes on Aesthetics: I,” Portfolio 10 (1879): 122. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ruskin, Fors Clavigera (July 1877); as quoted in Linda Merrill, A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992), 47: “I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Read together with the culinary parodies of Whistler’s art, Ruskin’s metaphor takes on added resonance as the Victorian term “paint-pot” may suggest association with the “stew-pot” simmering in a Victorian kitchen. ↵

- For a frequently cited instance of nineteenth-century assertions that drawing as a masculine property of art is superior to color as feminine, see Charles Blanc, Grammaire des Arts du Dessin (Paris: Jules Renouard, 1867), 22. ↵

- For specific references, see John Gage, J. M. W. Turner: A Wonderful Range of Mind (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 3–5, 244; and Walter Thornbury, The Life of J. M. W. Turner, R.A., vol. 2 (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1862), 195–96. ↵

- See Elizabeth Robins Pennell and Joseph Pennell, The Life of James McNeill Whistler (London: William Heinemann; Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1908), 1:164. ↵

- Chelsea in Ice (1864; Colby College Museum of Art) was described as “a flood of milk” in “Rembrandt, Titien, Vélazquez, Et Cie. Whistler, Successeur,” Punch, April 9, 1892, 180. Whistler’s paintings were likened to “sack and sugar” in “The Grosvenor Gallery,” Illustrated London News, May 12, 1877, 450. Punch likened “that Fugue in blue-major, with pizzicato background” to “Saki out of a six-mark jar”; see “The Studios: ‘Round First,’” Punch, March 17, 1877, 109. ↵

- For technical analysis of Whistler’s “sauce,” see Joyce H. Townsend, “Whistler’s Oil Painting Materials” and Stephen Hackney, “Colour and Tone in Whistler’s ‘Nocturnes’ and ‘Harmonies’ 1871–72,” in Burlington Magazine 136 (October 1994): 692–93 and 696–97. ↵

- For example, see Isabella Mary Beeton, The Book of Household Management (London and New York: Ward, Lock and Co., 1888), 452, 1134. ↵

- GUL PC 6:45 (AAA, 4687, 0542). ↵

- See Ian Miller, A Modern History of the Stomach: Gastric Illness, Medicine and British Society, 1800–1950 (London and New York: Routledge, 2016). ↵

- See Susan Weber Soros, The Secular Furniture of E. W. Godwin, with Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), 226. ↵

- GUL PC 7:11 (AAA, 4687, 0588). ↵

- “‘Less Than (Man) Kind.’ A Lubbocky Sort of Fable,” Punch, January 28, 1888, 40. ↵

- Sir John Lubbock, On the Senses, Instincts, and Intelligence of Animals, with Special Reference to Insects (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1888). ↵

- Selections from Pennell’s column in the Pall Mall Gazette were published as The Wares of Autolycus: The Diary of a Greedy Woman (London: John Lane, 1896) and in another edition, The Delights of Delicate Eating (New York, Akron, Chicago: Saalfield, 1901). On Pennell’s culinary writings, see Talia Schaffer, “The Importance of Being Greedy: Connoisseurship and Domesticity in the Writings of Elizabeth Robins Pennell,” in The Recipe Reader: Narratives–Contexts–Traditions, ed. Janet Floyd and Laurel Forster (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2003), 105–26. ↵

- Pennell, The Delights of Delicate Eating, 93–94. ↵

- Ibid., 148, 97. ↵

- See Menpes, Whistler as I Knew Him, 52: “Whistler cooked, as he painted, with marvelous skill and genius.” See also Margaret F. MacDonald, Whistler’s Mother’s Cook Book, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995). ↵

- The Pennells relate that Whistler’s old friends from West Point remembered “his fondness for cooking and the excellence of his dishes,” as quoted in Pennell and Pennell, The Life of James McNeill Whistler, 1:36. ↵

- More than one hundred menus written by Whistler exist in the archive at University of Glasgow. According to Charles Augustus Howell, “Whistler wrote out a menu every morning—these he treasured as if they were drawings.” Note by Howell below Whistler’s menu of December 18 {1876} (Correspondence, GUL LB 11/112; GUW 02813; accessed June 15, 2017). ↵

- “Lettres de Londres: L’exposition internationale des inventions,” L’Art Moderne, August 30, 1885, 281 (my translation into English): “Chacun sait, d’ailleurs, que si l’auteur des Symphonies et des Nocturnes est un des plus grands artistes de l’époque, il est aussi le premier cuisinier de son temps. . . . S’il n’est pas donné à tout le monde de peindre comme Whistler, il est plus difficile encore d’égaler son génie culinaire.” ↵

- Ibid. “Qui ne connait à Londres la sauce Whistler, cette sauce d’un jaune si délicat et d’un goût si parfait que nul, sauf le peintre, ne la réussit jamais?” ↵

- Correspondence, March 25 {1876}, GUL W872; GUW 06883 (accessed May 26, 2017). ↵

- Pennell, The Delights of Delicate Eating, 163–64. ↵

- Menpes, Whistler as I Knew Him, 52, describes Whistler offering “tinted rice pudding” and “butter stained apple-green” to harmonize with “the blue of one’s plate.” ↵

- Walter Dowdeswell noted in Whistler’s studio a “table covered with old Nankin china—for use as well as for sight”; quoted in Pennell and Pennell, The Life of James McNeill Whistler, 2:27. On Whistler and Chinese porcelain, see Aileen Tsui, “The Painter as Collector: East Asian Objects and James McNeill Whistler’s Abstracting Eye,” in Inventing Asia: American Perspectives Around 1900, ed. Alan Chong and Noriko Murai (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2014), 116–31. ↵

- For the full menu of this meal from 18 January {1876}, see Correspondence, GUL W860; GUW 06871 (accessed June 15, 2017). ↵

- {H. G. Wells}, “A Misunderstood Artist,” Pall Mall Gazette 58, no. 9235 (October 29, 1894): 3. For Wells’s views of Whistler, see Robert Slifkin, “James Whistler as the Invisible Man: Anti-Aestheticism and Artistic Vision,” Oxford Art Journal 29, no. 1 (2006): 53-75. ↵

- See Whistler, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (London: William Heinemann, 1890), 137. ↵

- {Wells}, “A Misunderstood Artist,” 3. ↵

- Immanuel Kant, “Analytic of the Beautiful,” in The Critique of Judgement, trans. James Creed Meredith, ed. Nicholas Walker (Berlin, 1790; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 35–74. ↵

About the Author(s): Aileen Tsui is the Nancy L. Underwood Associate Professor of Art History at Washington College, Chestertown, Md.