Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archeology of Memory

PDF: Arellano Vences, review of Amalia Mesa-Bains

Curated by: María Esther Fernández, artistic director of the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, and Laura E. Pérez, professor and chair of UC Berkeley’s Latinx Research Center

Exhibition Schedule: Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, CA, February 4–July 23, 2023; Phoenix Art Museum, November 2023–March 2024; El Museo del Barrio, April–August 2024; San Antonio Art Museum, October 2024–January 2025; and the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Arts and Culture, March–August 2025.

Catalogue: Amalia Mesa-Bains: The Archaeology of Memory, ed. Laura E. Pérez and María Esther Fernández (Berkeley: UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive & Oakland: University of California Press, 2023)

As I entered the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive to visit Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archeology of Memory, I felt at home—embraced by the deluxe surfaces that make up the first chapter of Mesa-Bains’s celebrated series, Venus Envy. For many of us—children of working-class Mexican Catholics—the coalescence of silky satin textiles, lace, pearl rosaries, beaded candles, intricate altars, and a Patrón tequila bottle are an alchemic remedy to homesickness. This visual splendor of Chapter I: First Holy Communion, Moments Before the End (fig. 1) evokes the Baroque-esque paisa panaché1 that many of us reserve for regal festivities scheduled in accordance with Catholic sacraments (ex., el bautizo/baptism). From an early age, we get lost in closets, selecting and repurposing clothes, then dressing to impress in gleaming textiles and an array of shiny accessories. We partake in what Jillian Hernandez calls an “aesthetic of excess” to “make oneself hypervisible, but not necessarily in an effort to gain legibility or legitimacy”2—instead, we assert our personhood for ourselves through these affirmations. This exhibition is, for us, about belonging.

This is the inaugural retrospective dedicated to the influential Chicana artist and intellectual Amalia Mesa-Bains, and, for the first time, Venus Envy has been presented in its entirety, as a series that narrates significant episodes in Mesa-Bains’s life in four chronological chapters.3 Chapter I: First Holy Communion, Moments Before the End is divided into three parts: the Boudoir Chapel, Museum of the Self, and the Hall of Mirrors. They respectively spatialize the narratives of the bride, the nun, and the virgin. The sumptuousness of Chapter I is multiplied by Hall of Mirrors, set along a singular wall, reflecting the colorful accent walls and luminous surfaces of the installation. Museum visitors appear to serendipitously walk in and out of the mirrors, and newer arrivals are animatedly lured into the exhibition.

A concept that runs throughout the exhibition is domesticana, a term developed by Mesa-Bains. Domesticana is an aesthetic modality that attests to the artistic counternarratives of the domestic vernacular that have been historically attributed to Chicana women.4 As Jennifer A. Gonzalez aptly describes, domesticana is “the method by which the complex material iconography of a gender-specific domesticity is brought into the public space of exhibition to actively construct a new ideology and iconology of display.”5 It is often regarded as a feminist iteration of rasquachismo—a Chicano sensibility “rooted in resourcefulness and adaptability yet mindful of stance and style.”6 In First Holy Communion, Moments Before the End, objects central to institutionalized Catholic sacraments are organized along with a pantheon of Chicana icons, mystic writings, the Aztec goddess Coatlicue’s apparition on a vanity mirror, and personal mementos, including photographs and artworks of and by Mesa-Bains’s peers. This critical amalgamation crafts a visual Chicana feminist text reminiscent of Sylvia Morales’s short film Chicana (1979). As in Morales’s Chicana, Mesa-Bains embraces pre-Columbian and colonial ancestral connections as foregrounding the achievements of Chicana and Mexican women from social movements, calling on a feminist collective memory of resilience.

The presentation of Venus Envy continues in the following gallery, where the opened eaves of an emerald armoire expose a set of lustrous garments with floral motifs that welcome visitors into Chapter II: The Harem and Other Enclosures (1994/2022). This chapter is spatially conceived in three distinct sections: The Harem scrutinizes marriage and notions of sisterhood under patriarchal religious societies; The Library of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz pays homage to the feminist intellectual legacy of Sor Juana (1648–1695), who critiqued sexism in New Spain; and The Virgin’s Garden personifies the Virgin of Guadalupe through a carnal presence alluded to by a suite of outfits that are ready and available for her next outing (fig. 2).

Unlike the cloaks that hang in The Virgin’s Garden, the Vestment of Copper and Vestment of Feather in Chapter III: Cihuatlampa, the Place of the Giant Women (1997) do not fit an armoire or a closet (fig. 3). They are beyond life-size, retrofitted for a body that knows no bounds. For this chapter, Mesa-Bains references Cihuatlampa, the Aztec realm designated to women who died giving birth, and the feminist legacies of Amazon warrior women in Greek mythology.7 The imposing monumentality of these garments goes beyond the corporeal; they allude to the disdain wielded toward women who, like Mesa-Bains, defy docility and are deemed to be “too much.” As Mesa-Bains stated to Lowery Stokes Sims in a conversation for the exhibition catalogue: “It’s not even about the[ir] size. It’s about their brains, about their actions, about their advocacy, about their fearlessness.”8 It’s about the combative ways in which communal care can manifest, whether as spirits of childless Aztec women in hopes of displacing their motherly instincts, or as Amazons, whose “myths” have recently been attributed to the histories of Scythian women fighters of the Eurasian Steppe.9

The last of the Venus Envy chapters, Chapter IV: The Road to Paris and its Aftermath, The Curandera’s Botanica (2008/2023), deals with Mesa-Bains’s own healing journey following a near-fatal accident.10 In this particular installation on the medicines of a curandera, or traditional healer, Mesa-Bains presents healing as “the space between life and death.”11 The work contains the wondrous materiality associated with Western and non-Western healing practices. A metal multi-shelved cabinet capped by an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe houses personal mementos, while glass beakers and other scientific tools are splayed atop a metal laboratory table interspersed with devotional and healing objects found in botanicas (small spiritual goods stores). Notably, artifacts pertaining to Afro-Caribbean religious practices, such as candles dedicated to the Yoruba deity Chango, are also found in this installation. They allude to her late friend and “soul brother in the making of art of the sacred,” the gay Afro-Cuban American artist Juan Boza Sánchez (1941–1991), who introduced Mesa-Bains to the elements of his Santería faith and Afro-Caribbean botanicas.12 As a memorial across cultures on spiritual healing, the closing chapter of Venus Envy charts the future of domesticana as domesticanx, an intersectional version of the term encompassing queer and Latinx feminisms as elaborated by curator Susanna Temkin in her recent show Domesticanx at the Museo del Barrio.13

Various beautiful gestures of remembrance characterize the remaining works in the exhibition, such as the inclusion of the late Yolanda López’s Guadalupe series (1978) and photographs of Judith F. Baca as La Pachuca (1976). The exhibition closes with An Ofrenda for Dolores del Rio (1983/2023), an altar installation within a narrow niche from which pink curtains sensually flare out onto the protruding walls of the enclosure. In its first iteration, the installation included bobby pins from Yolanda López and a comb from artist Carmen Lopez Garza, as well as her mother’s powder puff.14 The shimmering, suspended curtains poetically reflect the brilliance of the installation surfaces and that of Dolores del Rio—the first major Latina crossover star in Hollywood, who abandoned the American film industry at the height of her success for Mexican cinema after becoming disenchanted by sexist typecasting.

Mesa-Bains’s installations, and by extension her retrospective, attest to the humanistic potential of narrative art. In a conversation with the Los Angeles–based artist Sandy Rodriguez, Mesa-Bains remarked that access to Indigenous histories and knowledge was not readily available to many Chicanas, and so they “imagine[d] what that was like.”15 That is, she authors a narrative along the formal qualities of literary genres such as speculative nonfiction, incorporating personal and historically charged objects not to document memory but to evoke it. This is both a thematic concern and a conceptual narrative form that provides hope while enduring times of uncertainty.

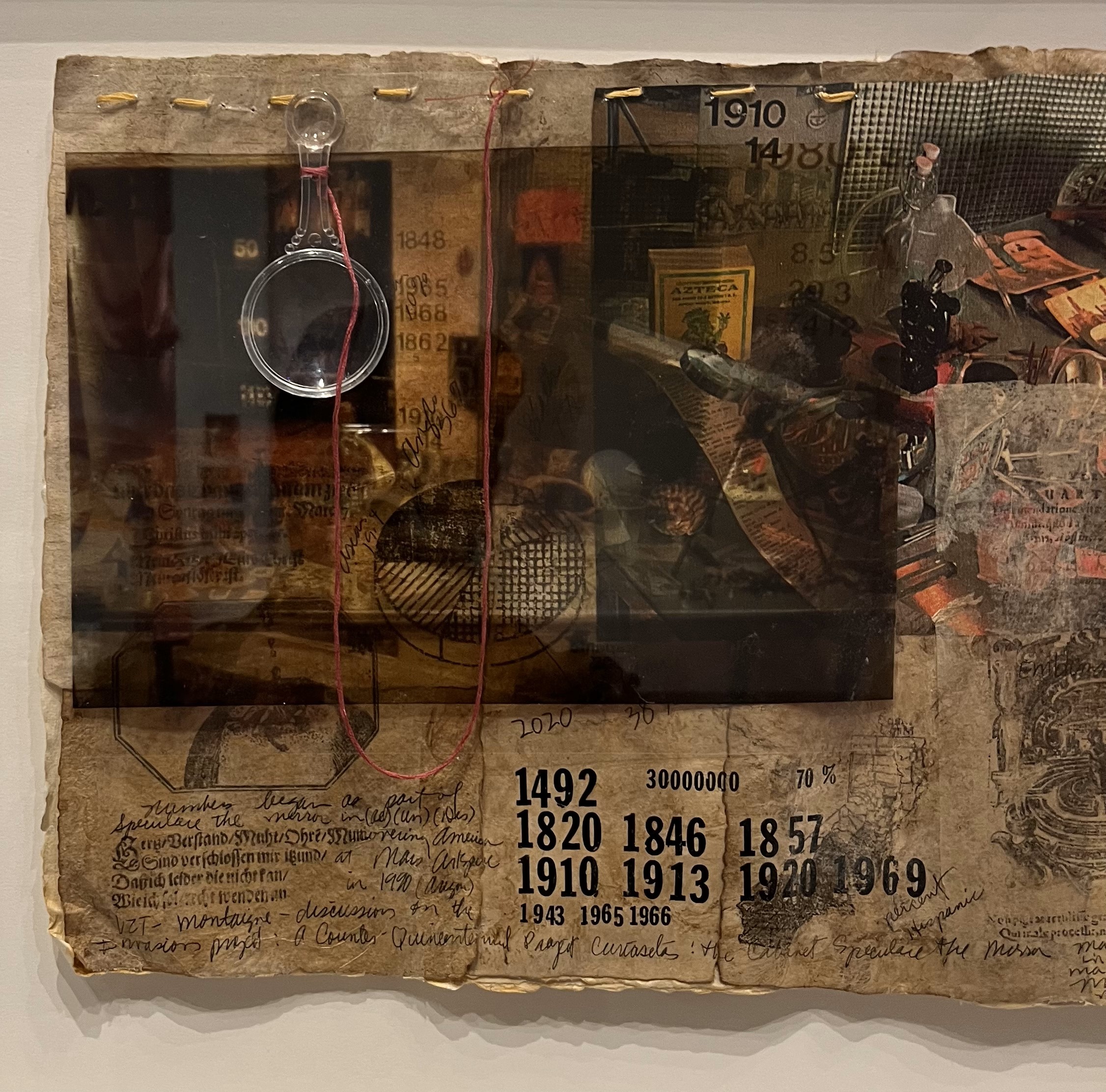

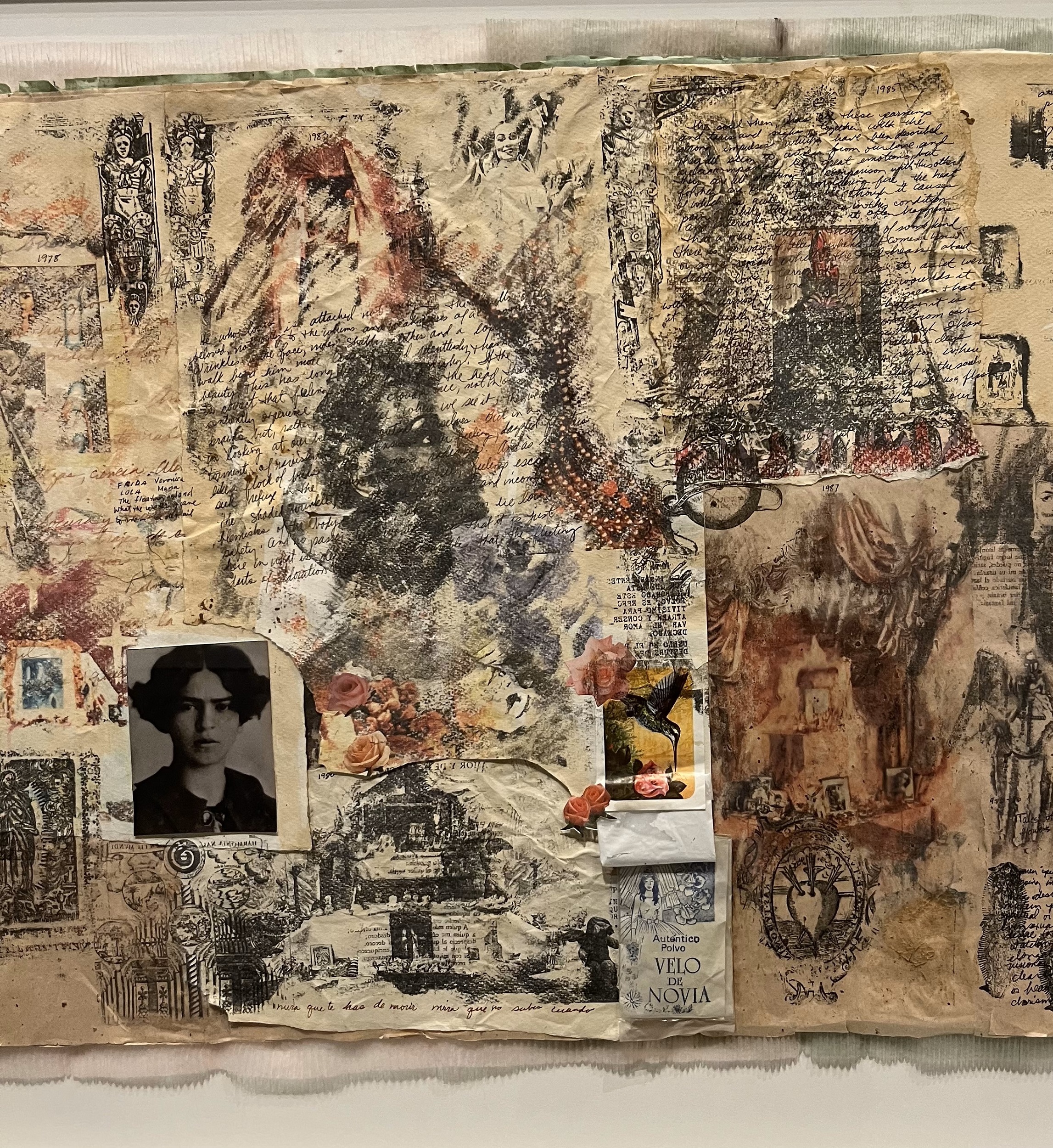

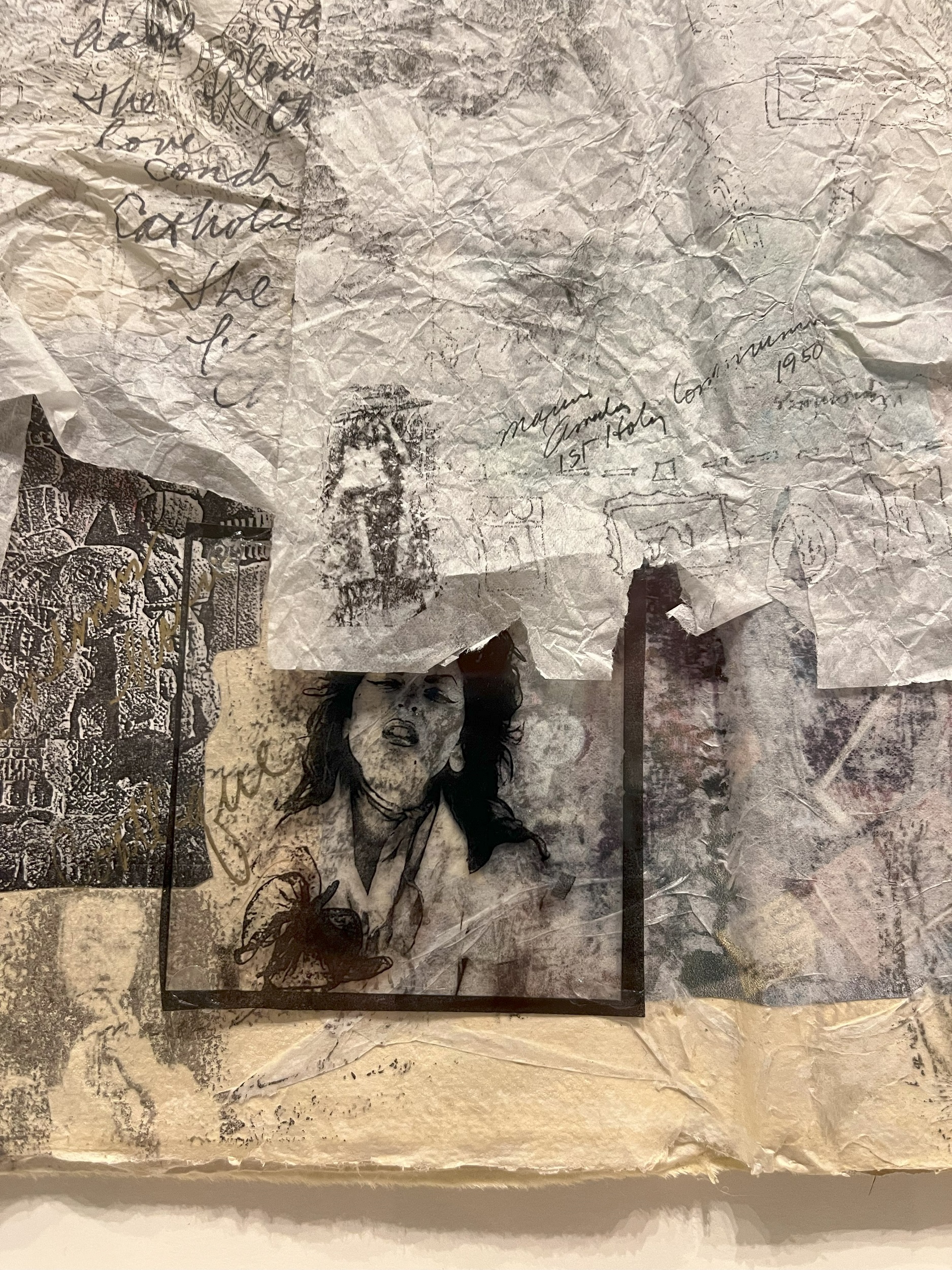

Mesa-Bain’s investment in a feminist collective memory sees her working along with and against archives. Her practice formally echoes Saidiya Hartman’s critical fabulations as she contends with the racist and patriarchal historical treatment of women of color.16 As is the case for Hartman, narrative restraints are essential to Mesa-Bains’s work. In the exhibition, these come in the form of visual ruptures. The more apparent of these are rendered via the sparkle of glistening and reflective materials, as well as through ornate textiles that often possess radiant qualities of their own. There is also an opacity to the sedimentary-like stacking of Mesa-Bains’s altar installations and various works on paper, such as Codex Goddesses, Virgins, and the Holy Communion (figs. 4–6), that does not grant closure to the livelihoods and relationships established across the exhibition. As much as these enclosures have historically sought to affirm a cis-hetero-patriarchal logic, it is precisely in these spaces where women have negotiated ways of being and created meaning that exceed the physical restraints placed on them. The survivalist kinship that Mesa-Bains threads through her reconceptualization of these settings results in an embracive and nurturing domesticanx counternarrative that reestablishes the sacredness of home and family. Mesa-Bains’s long-awaited retrospective graciously reminds us that “Memory heals the wounds of those who came before us.”17 As such, perhaps during your visit, you too might find some ease to what ails you.

Cite this article: Javier Arellano Vences, review of Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archeology of Memory, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17553.

Notes

- Paisa panaché: a modality and aesthetic of excess that fuses Western/ranchero fashion with baroque prints such as those found in Gianni Versace’s Summer 1992 collection. It is a proto-Buchon aesthetic that became prominent in Southern California and disseminated broadly to other regions within the United States and Mexico. The style was shaped mainly by the popularity of the corrido icon Chalino Sanchez and other Mexican and Mexican American musicians of the 1990s, who took on a dynamic and contemporary fashion style that expressed a sense of elegance and decadence without disavowing their rural familial origins. ↵

- Jillian Hernandez, Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 11. ↵

- For more, see Jennifer A. González, Venus Envy: Chapters I–IV (Mendocino, CA: Moving Parts Press, 2022). ↵

- Amalia Mesa-Bains, “‘Domesticana’: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache,” Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies 24, no. 2 (Fall 1999), 160. ↵

- Jennifer A. González, “Amalia Mesa-Bains: Divine Allegories,” in Subject to Display (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 134. ↵

- Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, “Rasquachismo: A Chicano Sensibility,” in Chicano Aesthetics: Rasquachismo (Phoenix, AZ: MARS, Movimiento Artístico del Rio Salado, 1989), 5. ↵

- Amazon was also the name of a feminist women’s publication based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from 1972 to 1974. Notably, their second issue covered the arrest of the Chicana leader of the Milwaukee Prisoners Solidarity Committee (PSC), Benita Orozco, following her involvement in demonstrations against the Attica massacre in September 1971. For more, see Amazon: A Feminist Journal (1972–1974) Women’s Studies Archive, https://wislgbthistory.com/media/print/amazon.htm. ↵

- Amalia Mesa-Bains and Lowery Stokes Sims, “In Conversation: Amalia Mesa-Bains’s Feminisms,” in Amalia Mesa-Bains: The Archaeology of Memory, ed. Laura E. Pérez and María Esther Fernández (Berkeley: UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive & Oakland: University of California Press), 59. ↵

- Theresa Machemer, “Tomb Containing Three Generations of Warrior Women Unearthed in Russia,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 30, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/tomb-containing-three-generations-amazon-warrior-women-unearthed-russia-180973877. ↵

- Amalia Mesa-Bains, “Sixty Objects in My Art Life,” in Amalia Mesa-Bains: The Archaeology of Memory, 29. ↵

- Mesa-Bains, “Sixty Objects in My Art Life,” 29. ↵

- Mesa-Bains, “Sixty Objects in My Art Life,” 3.; Mesa-Bains met Boza Sánchez in the 1980s while organizing the exhibition Ceremony of Memory at the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art in New York. ↵

- Ivana Cruz, “Exploring the Idea of Domesticanx Through Art,” W Magazine, February 6, 2023, https://www.wmagazine.com/culture/domesticanx-museo-del-barrio-museum-artist-interview. ↵

- María Esther Fernández, “Amalia Mesa-Bains: Storytelling and the Archeology of Memory,” in Amalia Mesa-Bains: The Archaeology of Memory, 14. ↵

- “In Conversation with Amalia Mesa-Bains,” roundtable discussion with Amalia Mesa-Bains, Jennifer A. González, Sandy Rodriguez and Adriana Zavala, UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, CA, February 18, 2023. ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26 (June 2008): 1–14. ↵

- Amalia Mesa-Bains, “Neo Hoodoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith,” accessed April 1, 2023, https://amaliamesabains.com/exhibit/neo-hoodoo-art-for-a-forgotten-faith; Amalia Mesa-Bains, Healing Book, in Venus Envy Chapter IV: The Road to Paris and its Aftermath, The Curandera’s Botanica (2008/2023). ↵

About the Author(s): Javier Arellano Vences is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art & Art History at Stanford University