Norman Parish’s Historical Gyrations

PDF: Lobel, Norman Parish’s Historical Gyrations

When I first read Panorama’s call for short essays highlighting artists who “have embraced, critiqued, or reformulated iconic American symbols in their practices,” my mind instantly flew to one particular work of art: Norman Parish’s Gyrations of American Gothic (fig. 1).1 Parish’s painting is a simultaneous reworking of and rebuke to one of the most iconic images of twentieth-century American art, one that has been shown in countless art history lectures, has appeared in numerous survey textbooks, and has inspired untold pop culture riffs and parodies. Gyrations of American Gothic is not just a racial recasting of Grant Wood’s famed Regionalist picture, with the Black couple at right replacing Wood’s tight-lipped Midwestern farming pair, inasmuch as Parish significantly expanded the composition into a much wider, horizontal format, offering up many more figures and motifs in the process. In so doing, the artist made clear that his interest was not simply a painterly revision of Wood’s earlier effort but rather a broader critique of putatively American national symbols. Hence the inclusion of the flag, which takes up much of the composition’s lower left quadrant, and the young man with his fist raised in an immediately recognizable Black Power salute, which simultaneously echoes and serves as a rejoinder to the Statue of Liberty’s similar pose just to the right.

Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 in. DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center. Courtesy of the artist’s estate

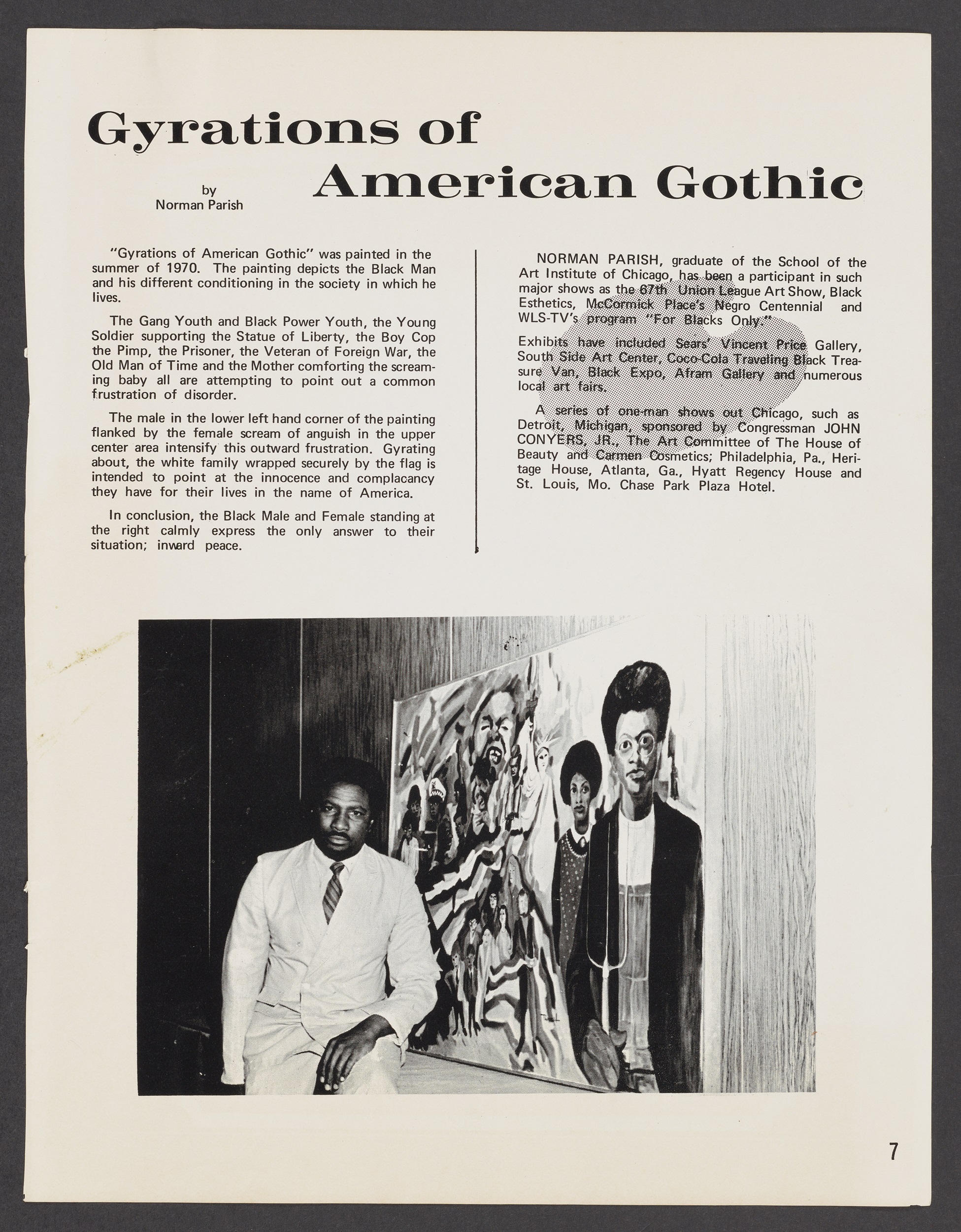

Gyrations of American Gothic was clearly an important work for its maker. Parish had himself photographed with the painting, staring directly out at us not unlike his Grant Wood–derived protagonist (fig. 2), and he additionally wrote an explanatory text to accompany the work. The latter detailed how the picture was an attempt to convey particular aspects of Black American life, from the experience of such varied emotions as peace, frustration, and anguish to the awareness of racial disparities, which Parish described as “the Black Man and his different conditioning in the society in which he lives.” (Parish’s gendered language, and the smaller size he gave to the farmer’s female companion, suggest he was approaching things from a distinctly masculine perspective.) The text makes clear that the effects of racism, and the differential treatments afforded to Black and white Americans, were central to the artist’s iconographic approach, as when Parish explains how “the white family wrapped securely by the flag is intended to point at the innocence and complacency they have for their lives in the name of America.”

While Wood’s picture is known by the vast majority of people through photographic reproductions (as well as through its many spoofs and pastiches), Parish, for his part, must have known it firsthand, even intimately. Wood’s painting had been in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago since 1930 (the year it was made), and so Parish, who had been a student at the School of the Art Institute, would have had plenty of opportunity to view it directly and up close. At the same time, Gyrations filters that immediate contact with a well-known work by a white artist through Parish’s deep involvement in the Black art scene in Chicago, including his role in the creation of, and subsequent controversy around, the Wall of Respect, an important 1967 community mural project on Chicago’s South Side.2

This Colloquium asked for something further—not just the highlighting of such revisionist works but also some comment on what we might learn from them. What, then, might Parish’s picture teach us? In the simplest terms, we might consider that Parish was pursuing an artistic strategy not dissimilar to what both curators and art historians do in their professional roles: he was looking back at a historical work of art and reframing it in ways that made it newly relevant and resonant in and for the present. And he was doing so with not just any artwork but one which by that point had become practically synonymous with American national identity. He was also highlighting how the meanings of such symbolically resonant artworks were not static but inevitably changed over time, as shifts in the broader culture led to different audiences and new interpretations. He was using the image in a way Wood almost certainly could never have imagined, reshaping it into a searing indictment of the nation’s continuing history of racism and Black citizens’ response to that painful and shameful legacy. As such, Parish’s effort is not so much a rejection of Wood’s picture as a creative reworking of it, an intervention into art history to make it usable for himself and his community in the present. In the end, isn’t that basically what curators and art historians find themselves tasked with doing, over and over and over again?

Cite this article: Michael Lobel, “Norman Parish’s Historical Gyrations,” in “American Artists x American Symbols,” ed. Katherine Jentleson, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19346.

Notes

- While some sources give the painting’s date as 1969, a period text written by Parish, now held in the artist’s papers at the Archives of American Art, clearly states that it was “painted in the summer of 1970”; see Norman Parish, “Gyrations of American Gothic,” undated clipping, Parish Gallery records, box 7, folder 2, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. For the 1969 date, see Evan Carter, “Past Time Has Come Today,” New Art Examiner 33, no. 2 (November–December 2018), 7. My thanks to Norman Parish III and Rebecca Zorach for helpfully supplying further information about the dating of Gyrations of American Gothic. ↵

- On Parish’s role in the Wall of Respect and the subsequent controversial whitewashing of his contribution to the mural, see Rebecca Zorach, Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965–1975 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). ↵

About the Author(s): Michael Lobel is professor of art history at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY.