Self-Portraits and Photocopies: Anita Steckel’s Feminist Collage

PDF: Middleman, Self-Portraits and Photocopies

Published in 1978, Copy Art: The First Complete Guide to the Copy Machine opens with the bold statement: “Welcome to the age of Copy Art. Now anyone has the potential to be an artist or designer at the push of a button.”1 Included among the book’s many examples is an illustration of Anita Steckel’s (1930–2012) photocopy work Creation Revisited (1977; fig. 1). In this aggregate image, a nude Steckel soars across Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, riding on the back of a giant bird. “Revisiting” the biblical creation story that omits the female body, Steckel simultaneously addresses that absence and puts herself in dialogue with art history. Exploring the tension between Steckel’s desire for recognition as an artist and her irreverent approach to art making encapsulated by this work, I argue for a feminist interpretation of both her techniques and choices of media, which together posed subversive challenges to the stereotypes of artistic identity with which she contended. Despite the enthusiasm of Copy Art’s authors, Steckel’s appropriation points to the fact that easy-to-use technology alone was not enough to make anyone an “artist.”

The use of mechanically produced, found imagery and its transformation, by her hand, into imaginative fantasies and social critiques were hallmarks of Steckel’s oeuvre. This essay tracks her development of this method in combination with the self-portrait as the key components in expressing her growing feminist activism from the early 1960s through the 1970s. I focus on the public display of her work in five solo exhibitions in and around New York City, bookended by Mom Art at Hacker Gallery from May 21 to June 29, 1963, and Anita Steckel: Collage at Hansen Galleries from April 5 to May 1, 1977, in which she debuted “several hundred works” made with a Xerox machine.

Mom Art, which included a series of found portrait photographs and printed reproductions of famous works of art that Steckel had overpainted to create surreal compositions with social commentary, was Steckel’s first exhibition to showcase her methods of appropriation. The title of the show, Mom Art, put Steckel’s work in conversation with Pop Art while also protesting the category, which the press had all but solidified into a canon of male artists. Of course, Steckel knew that the term “pop” referred to pop culture, but her oppositional label drew out the underrecognized yet blatant sexism of Pop art and its reception. The slippage between the title of the exhibition and one reviewer’s reference to her as a “lady painter” lays bare the double bind for artists of her generation who made work that challenged sexism while also attempting to establish their reputations as artists in the New York art world.2

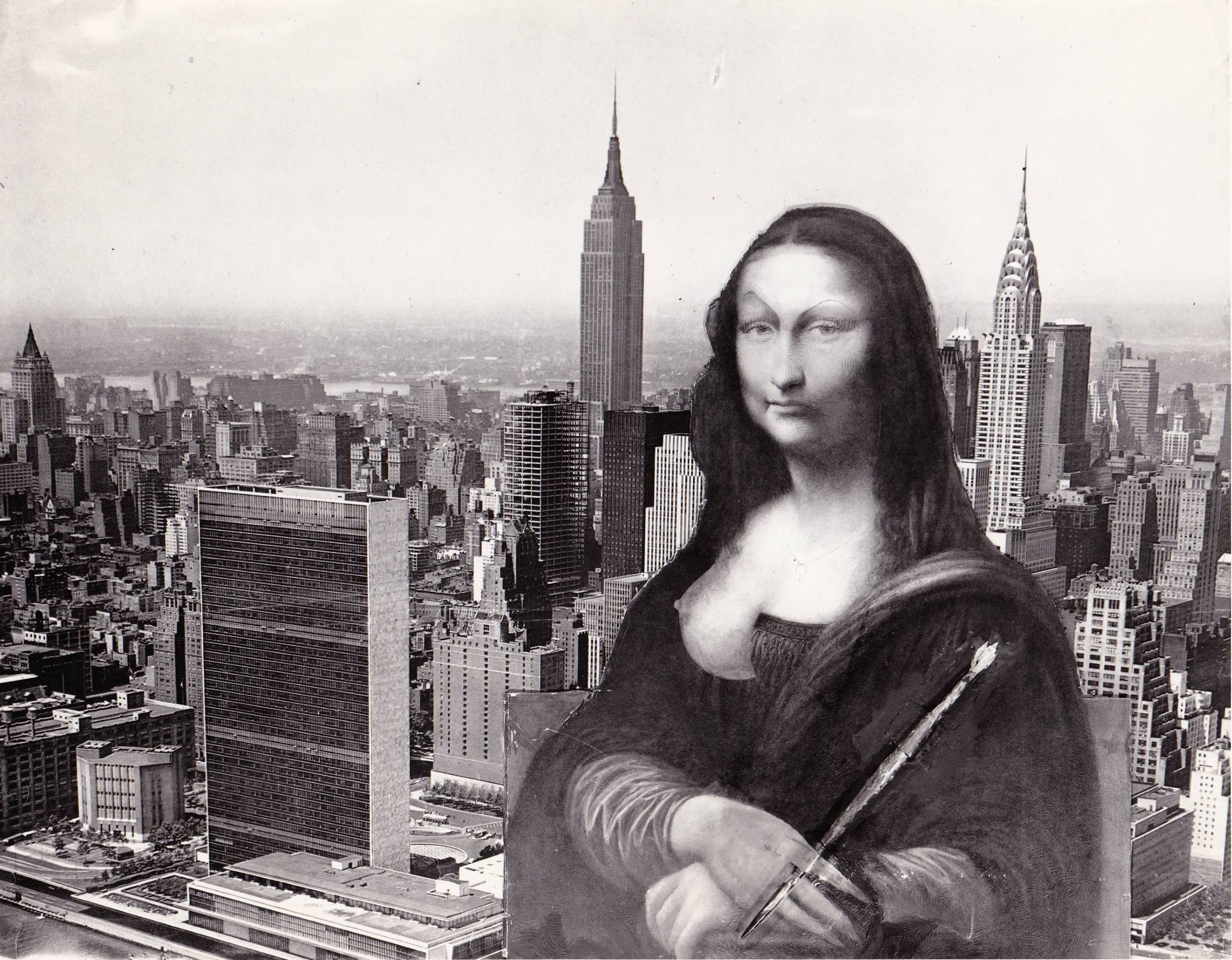

Like the Pop artists, Steckel borrowed from art history and mass culture in her appropriation of reproductions, often with a sense of humor. In Girl Scout (1963), Steckel painted a nude female figure standing atop the heads of the male rowers in a cropped reproduction of Thomas Eakins’s 1872 painting Biglin Brothers Racing. Rather than blending in, the nude “girl scout” stands out, larger than the athletic male bodies, and leads the eye, and perhaps the narrative, in a different direction. Steckel’s additions to vintage photographs altered the subjects in ways that likewise gave rise to new and political dimensions. In Das Wunderkind (1963), Steckel refashioned a photograph of a baby into a humorous commentary on gender and class (fig. 2). Playing with signs of femininity and sophistication, Steckel painted a pair of women’s legs fitted with high-heeled shoes on the infant and surrounded her with fur and lace. Amended with the delicately blended oil paint, the child now sits holding a martini glass with a cigarette dangling from her mouth, raising questions about the absurdity of gender socialization. The colorful decorative endpapers with which she framed the Mom Art montages, including Das Wunderkind, also allude to the social construction of femininity and its association with decorative arts and crafts. Refusing her then-husband’s suggestion to use a plain white mat, Steckel anticipated Miriam Schapiro’s term “femmage”—a type of collage, montage, and assemblage that embraces a history of such techniques as sewing, appliqueing, cutting, and piecing, traditionally assigned as women’s activities.3 However, reviews of Mom Art noted her affinity with Dada (again the irony) and Marcel Duchamp in particular, and Steckel welcomed that association, too. She later conceived her own altered Mona Lisa, but instead of the woman becoming a man, as Duchamp once said of LHOOQ, Steckel’s New Mona Takes the Brush (1973) depicts the painting’s sitter with one breast bared, holding a paintbrush (fig. 3).4 New Mona’s raised eyebrow acknowledges the visual riddle presented to the viewer, whose gaze simultaneously produces and consumes the female artist.

Steckel’s next solo exhibition, at Kozmopolitan Gallery from March 1 to 29, 1969, featured her Multiple Image series (1964–68) and works that she later designated as part of the Giant Women on New York series (c. 1969–73). In the former, she added mixed media to posters made by Personality Posters Manufacturing Company of famous people, including Lenny Bruce, Charlie Chaplin, W. C. Fields, Sigmund Freud, Timothy Leary, Billie Holiday, and others (fig. 4). The imaginative layers of faces and nude figures that Steckel drew on each portrait photograph suggest the inner sexual psyche of her subjects. In some cases, she collaged a photograph of herself overlapping the celebrity faces, possibly her first experiments with incorporating her own image into works that were not strictly self-portraits (three other works in the exhibition were specifically labeled as such).

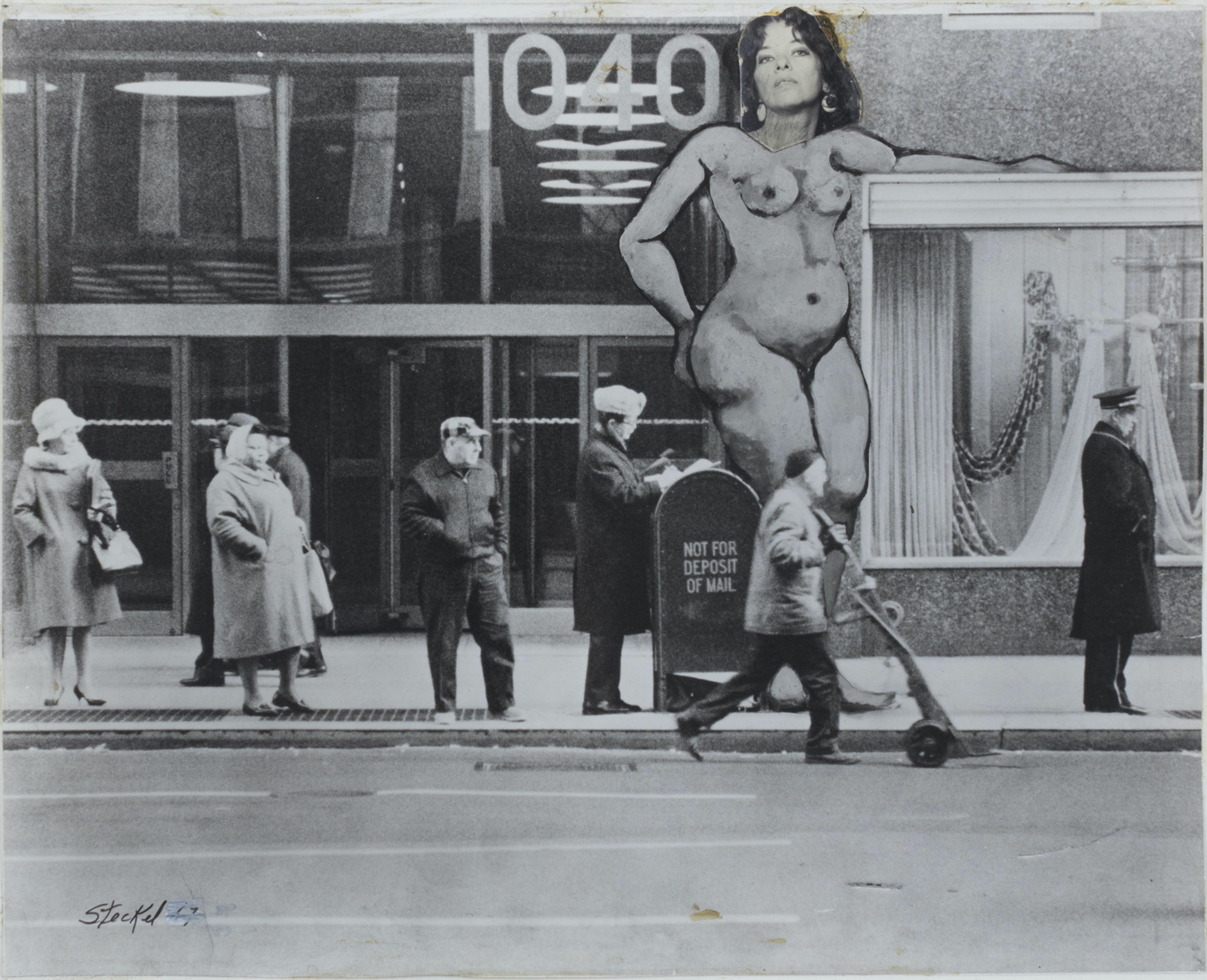

Reviews of this exhibition described Steckel’s “erotic fantasies,” declaring that it was “definitely her women in New York who steal the show.”5 These early versions of the Giant Women were relatively small compositions depicting anonymous female nudes drawn and painted onto found photographs and prints of New York City. In pieces such as Just Waiting for the Bus (c. 1967), the nude overtakes the everyday urban scene, out of scale with her surroundings (fig. 5). She also created black-and-white, approximately 20-by-24-inch reproductive print editions of select montages in the series, making them available in multiples and at a lower price. Indeed, prior to her use of the copy machine, Steckel understood that these images of giant women had a reproducible power that could be amplified through multiplication.

The circumstances of Steckel’s exhibition The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics, at Rockland Community College in Suffern, New York (February 2–25, 1972), pushed her activist spirit in a more organized feminist direction. Having received a phone call warning her not to bring any sexual work for the show if she wanted to be considered for a teaching position at the college, Steckel firmly decided not to “self-censor” despite the consequences of losing the potential of steady income. Furthermore, she chose a title for the exhibition that would make public her political stance. When a local legislator, John Komar, called on the board of the school to close the show, curators, critics, and academics sent letters and telegrams to the president of the college in support of Steckel, urging him to keep the exhibition open. In news footage covering the story, students at the school spar with Komar on the issues of censorship and artistic freedom. The most controversial aspect of The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics was not the female nudes but the abundance of male nudes and phallic imagery. Building on this momentum, Steckel’s next exhibition, Male Nudes (Plain and Fancy) (March 10–31, 1972) at Gallery 10, was noted in the Village Voice as the “first all male nude show by a woman in history.”7 While likely an exaggeration, the statement characterizes the sense of astonishment Steckel’s work elicited.

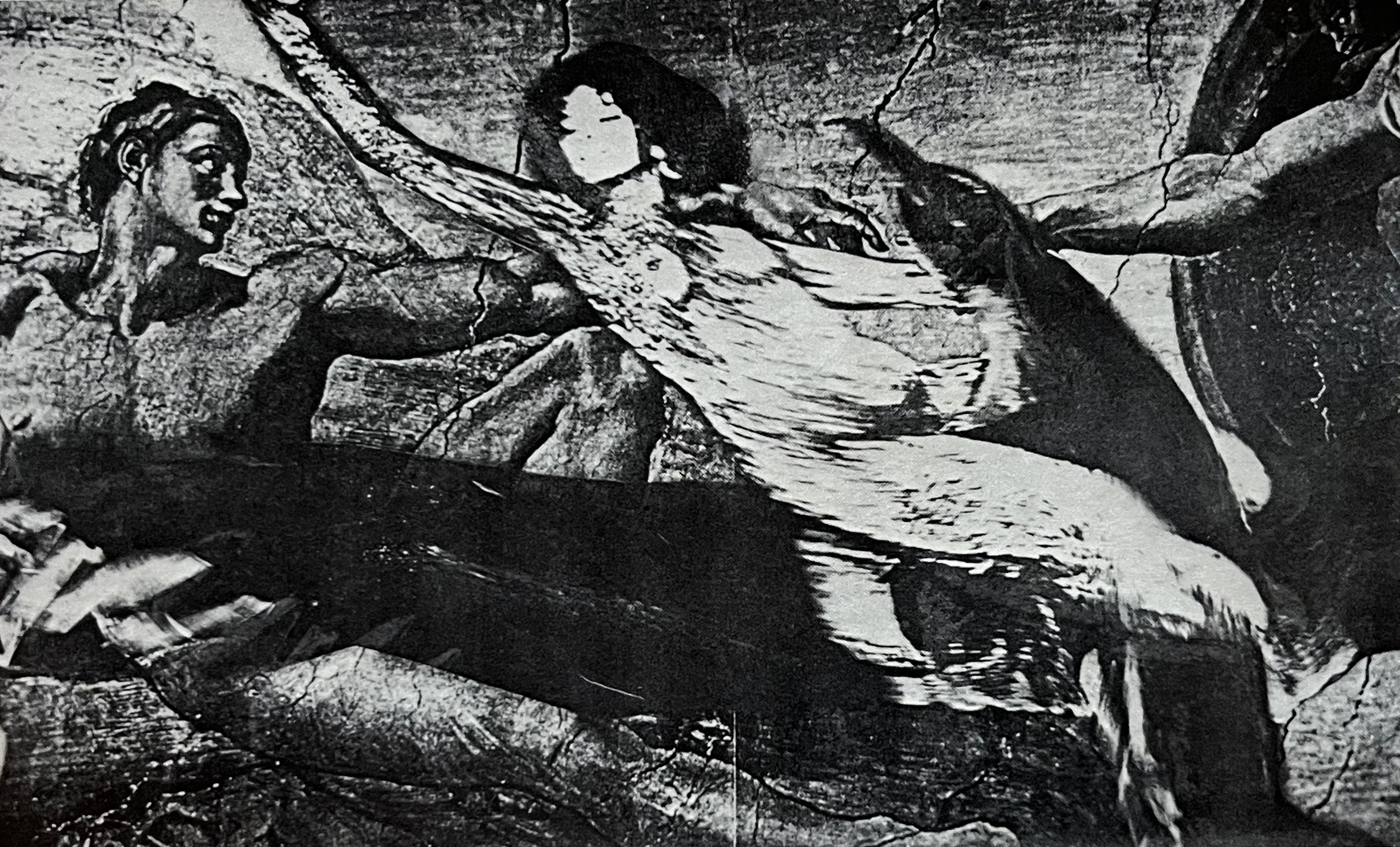

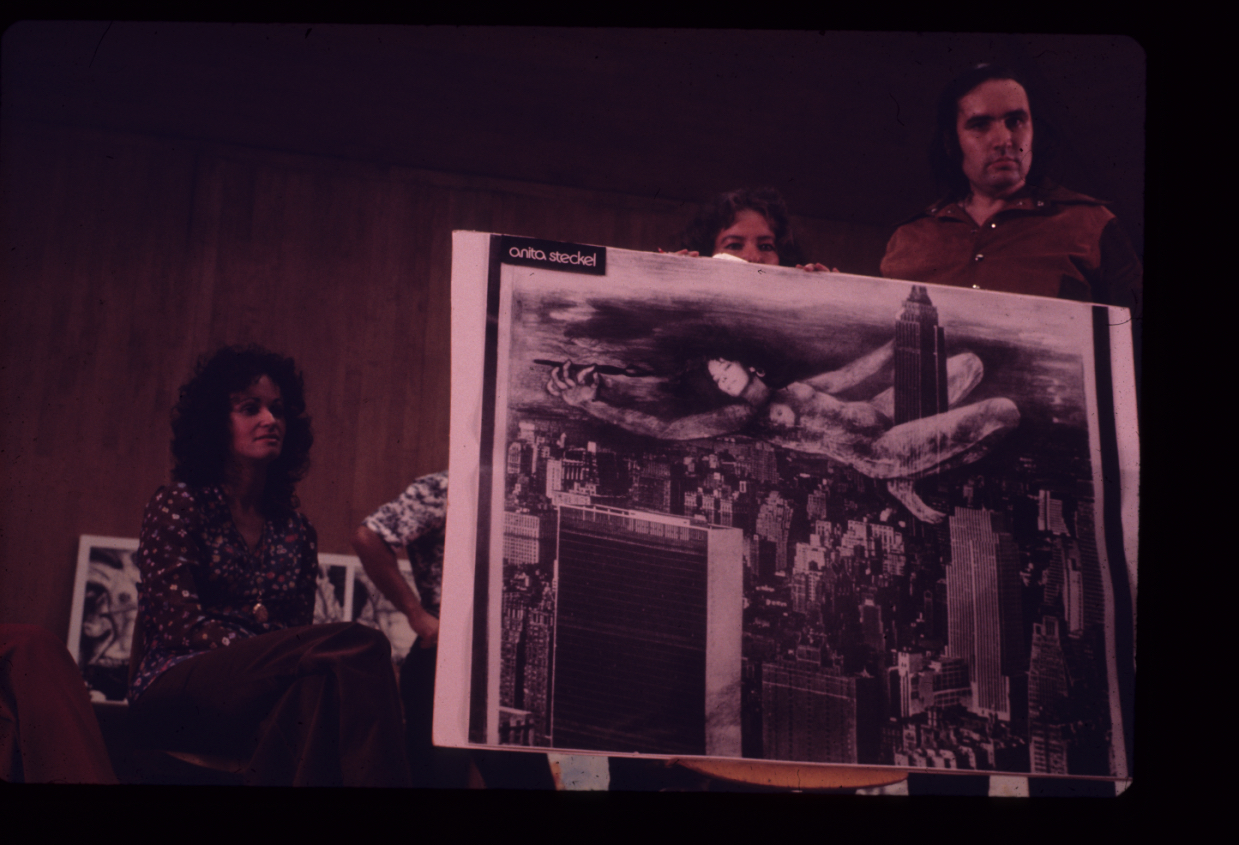

Following the attempted censorship of her 1972 exhibition for its sexual imagery, Steckel recreated her series of female nudes in the city with her own face, culminating as the Giant Women on New York series (c. 1969–74). She titled the series to oppose the condescending term “little woman” and increased the size of her works to approximately three by four feet. To make this final version of the series, she affixed cutout photographs of her face onto black-and-white photographs of the earlier versions (fig. 6). These small photocollages were then rephotographed to create an integrated surface and enlarged (fig. 7). Steckel continued to modify the resulting photographs, adding pencil and other media to their surfaces.

She exhibited the 1973 edition of gelatin silver prints in her NY Woman exhibition at Westbeth Gallery from May 4–28 that year, and she recalled the excited response she received, especially from women who visited the show. Adding her image to the nudes conspicuously incorporated the personal while seeking common ground with other women’s experiences. In Balancing Act (1973), for example, Steckel appears standing on one toe atop a boardwalk railing (fig. 8). Her ambiguous position between the young family and the heterosexual couple sitting on the benches below communicates a tentative displacement while she seems poised to leap into a dimension beyond those social identities. In Murder by Church Sanctioned Illegal Abortion (1973), her figure is crucified on a large white phallus painted onto a church nave. She explained, “In these pictures, the women are outsized, these are giant women. They’re women who have outgrown their roles, that is, the old roles that women have had. And I’m one of these women.”8

Steckel moved into Westbeth Artists Housing in the West Village of Manhattan in 1970. There she was enmeshed in an artistic community that regularly held performances and exhibitions, including several exhibitions of work by women artists. This is also where, along with fellow artists Louise Bourgeois, Martha Edelheit, Joan Glueckman, Eunice Golden, Juanita McNeely, Joan Semmel, Anne Sharp, and Hannah Wilke, she formed the Fight Censorship group.9 The group advocated for the acceptance of all types of sexual art made by women and fought against the gendered double standards of “decency” in galleries and museums.10 Steckel’s archive holds photographs of an appearance the group made with their work at the New School for Social Research in 1973 for a course titled “Pornography Uncovered, Eroticism Exposed.”11 The work Steckel chose to present was Giant Woman on Empire State (1973), in which her outstretched figure rides the building holding a paintbrush in a sweeping gesture over the skyline (fig. 9). Like the others in the series, the female nude appears as an intervention into the city that Steckel would have seen as the capital of the international art world. She insists on her presence not only as a woman but as an artist, signified by the paintbrush in hand. Thus, the same year that the Giant Women on New York series made its debut with her self-portrait nudes, Steckel’s feminist activism entered a new phase. In the following years, she showed in numerous women’s and feminist art exhibitions, and her work was featured in many publications, including Chrysalis, Heresies, Majority Report, Ms., Spare Rib, and Womanart.

Steckel’s combination of the self-portrait and the reproduction in the Giant Women on New York series began to play a central role in the conception of her feminist artwork. She melded these traditionally opposed ideas in art—the self-portrait conceived as individual and original versus the copy as multiple and inexpensive—to form a strategy for asserting an artistic identity that lies beyond this binary. On exhibition, the Giant Women were impressive in scale, but they could also be reproduced and circulated in feminist magazines without losing their iconic force.

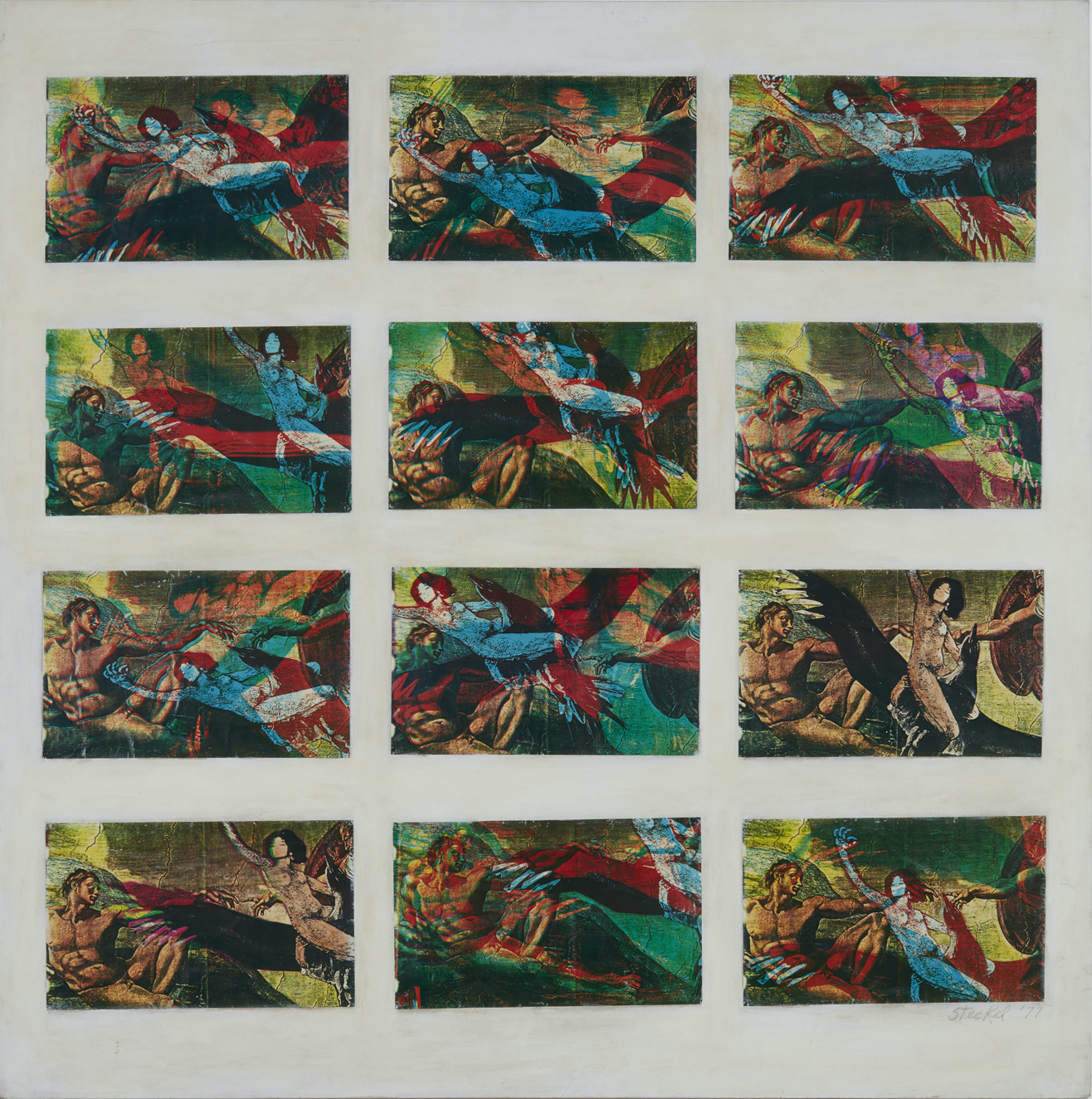

In a subsequent series, The Journey, Steckel transferred duplicated images of herself into new compositional configurations and narratives, in some iterations reusing the nude from Giant Woman on Empire State. Creation Revisited (1977), the Xerox print of a collage in which Steckel’s image, cut from the Giant Woman piece, rides on a large bird flying through Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, is one example (fig. 10). These images, and many like them, were photocopied extensively and in multiple and vibrant colors and then affixed to canvases to create larger compositions. Steckel explained:

I have removed the woman from the empire state building—and placed her-me on a bird. This image—woman on bird/woman in freedom . . . —then goes on a “journey” . . . flying high above New York . . . flying through the Last Supper . . . and most significantly through creation itself. The Journey in this way leads us to a place where history can be remade—woman flying full strength and power where she was denied her rightful place in creation.12

Through the method of collage, Steckel appears in Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, Pablo Picasso’s garden, and flying over New York City, among other environments created with borrowed backdrops. Her statement in Copy Art reads: “It’s really important for women to remake history and see themselves as acceptably part of history since they have been excluded or diminished by male written records. My recent work reflects spiritual and political freedom meshed with art freedom.”13

There is a substantial body of literature on female artists’ self-representation as a strategy for claiming a space for themselves as artists in the 1970s, while at the same time critiquing the history of discrimination and objectification in the discipline.14 Rather than repeat those arguments here, I want to look specifically at how Steckel used duplication and xerographic technologies to create a multitude of self-imagery. It should also be noted that in the Giant Women on New York and The Journey series, the figure’s nude body is rendered by the artist while her head is a photographic representation. Steckel thus addressed the double bind of a female artist working with “the female nude”; she challenged the model/artist divide differently than her peers, such as Hannah Wilke and Carolee Schneemann, whose photographic images of their own bodies were integral to their practice and therefore particularly daring, unconventional, and controversial, even in feminist discourses.

The authors of Copy Art proposed that “thanks to modern technology, copy art may well be the most democratic and spontaneous art form of our time.”15 While the democratic possibilities of photocopying, with its relatively inexpensive and fast methods, have been integral to countercultural production of visual culture, scholarship on art that uses this technology is limited, especially regarding women artists.16 This is not surprising considering the broader history of sexism in art’s reception, alongside the medium’s connections to commerce and conservation issues exacerbated by its ephemerality. It is likely that we have already seen the disappearance of much work produced. Furthermore, copies test the concept of a unique work of art, requiring some sort of external validation. In her review of Experiments in Electrostatics: Photocopy Art from the Whitney’s Collection, 1966–1986, an exhibition organized by Curatorial Fellow Michelle Donnelly at the Whitney Museum of American Art (November 17, 2017–March 25, 2018), Erica X. Eisen draws attention to the large proportion of women artists represented, exploring the underlying political dimensions of the medium. She argues:

Xerography contests the creator-copyist binary that had long been used to devalue the labor of women both in the arts and in the office. These works suggest that replication is an inherent part of creativity that copying itself can be executed in highly original ways. Women artists who made use of copiers in their artistic practice disrupted familiar narratives about the role of women in technological and artistic development, making innovative and often irreverent use of new technologies to create a body of work that tacitly criticizes the traditional dismissal of women’s intellectual capacity for invention.17

In the article, Eisen contrasts the notion of the “artist’s hand” emphasized in Abstract Expressionism with the next generation’s use of the copy, while arguing for a broader definition of what is considered “original.”

Steckel wanted to have it both ways, and she accomplished this in The Journey series by manipulating the pieces of paper as they were being copied by the machine. In “Copy Motion,” the section of Copy Art illustrating Steckel’s work, the text explains, “The most dramatic effects . . . are accomplished on the 6500 color copier which scans each original three times, once for each color [cyan, magenta, and yellow]. The ‘copy motion’ effect on the color machine is, in many cases, unpredictable and breathtaking.”18 (Xerox’s 6500, released in 1973, was the most widely available color copier in the 1970s.) Steckel’s Creation Revisited was made on such a machine by altering the color settings and pulling the image of herself on the bird across the underlying page as the machine ran, causing a blur (see fig. 10).19

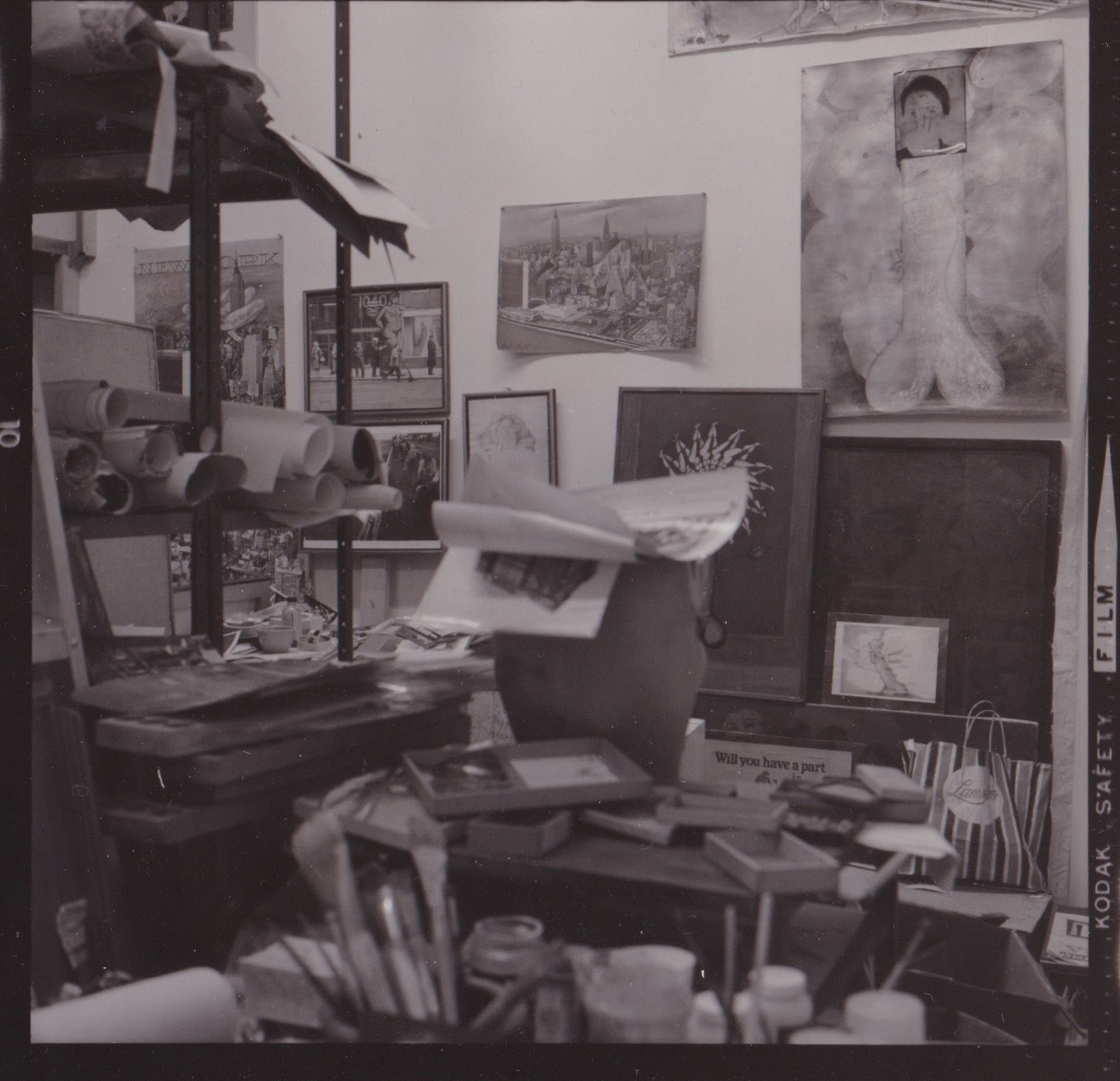

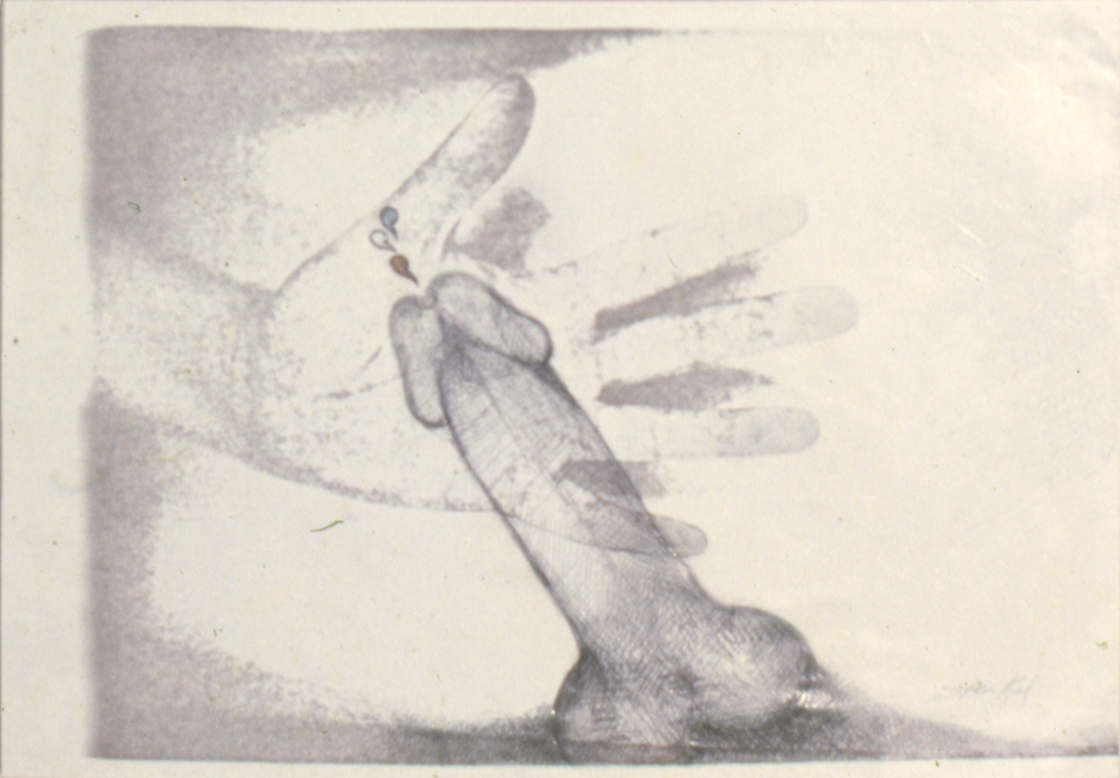

There is evidence in photographs of Steckel’s Westbeth studio that she had begun working with photocopies by the early 1970s, although she could have experimented earlier since black-and-white copy machines had become more accessible in the 1960s. Pictures show xerography prints of hands that Steckel transformed into sexual, figurative drawings, like a Surrealist summoning an image from the unconscious (figs. 11 and 12). In The Man (c. 1970s), she presents the erotic as a political protest, overlaying the outstretched hand with a drawing of an erect penis spewing red, white, and blue sperm. The artist’s hand is indexed in the process of making the image, arguably more directly than in the Abstract Expressionist gesture. In typical Steckel fashion, there is also an irreverence to pressing the hand on the glass or moving the document meant to be copied. Both techniques run squarely against operating instructions for achieving the clearest duplication. Yet the technology allowed her to make the copies by herself, quickly, and in greater numbers, and to manipulate the images during the process, creating an “original” or “unique” work each time.

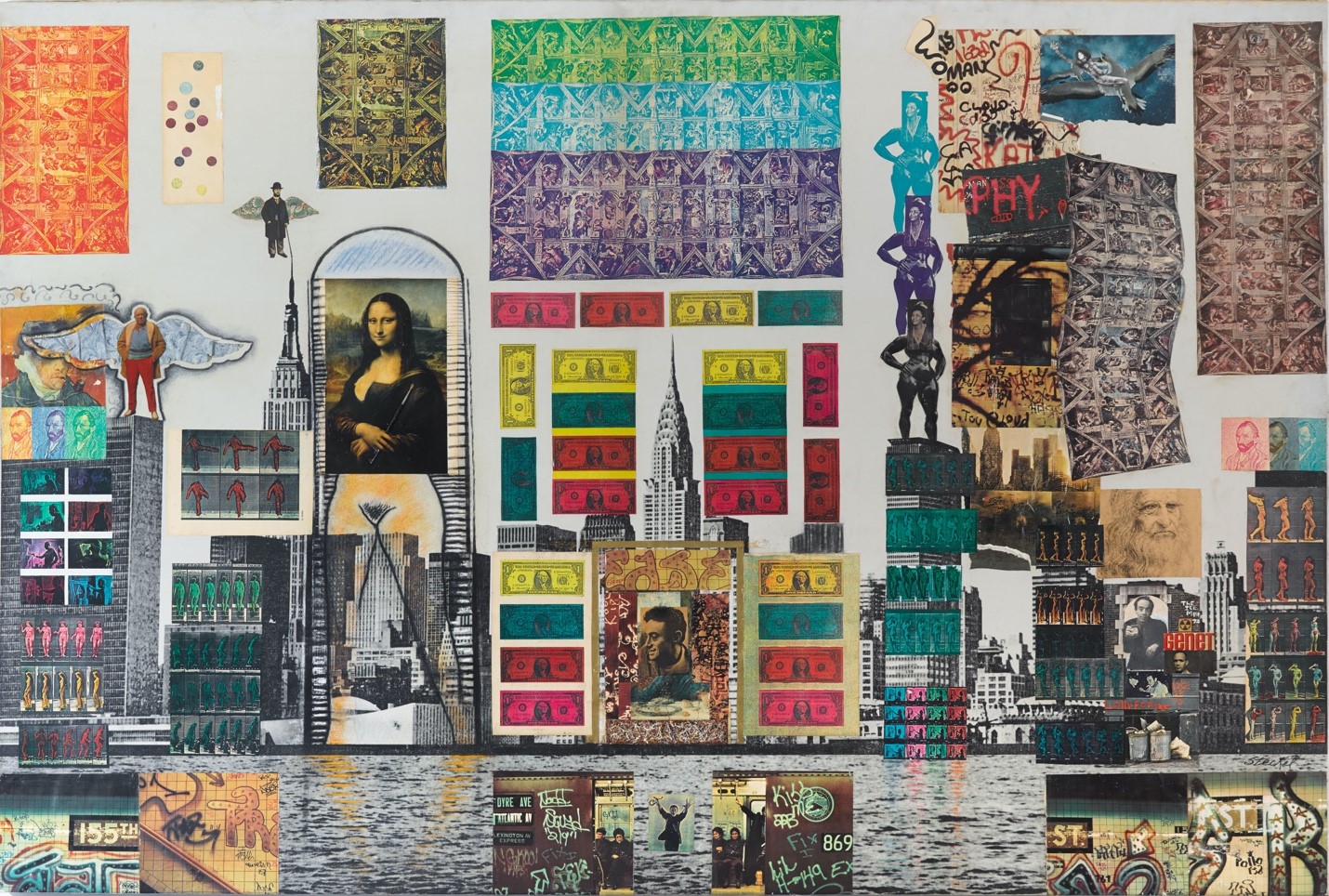

Anita Steckel: Collage, which opened at Hansen Galleries in April 1977, featured a kaleidoscope of these colorful Xerox copies. Installation photographs show copies glued to canvases or thumbtacked to walls, in multiple groupings, creating a DIY aesthetic that captures Steckel’s confident approach to her art, despite limited financial resources (fig. 13). On a table in one corner of the gallery sat four votive-like sculptures made of found images affixed atop wooden blocks and an offering box with dollar bills that Steckel had brightly colored and copied. Among the hundreds of works included in the show were many from The Journey series, in which her figure soars, both clothed and unclothed, over rooftops and through reproductions of historical artworks. Other series featured the faces of famous artists and performers, from Leonardo and Vincent van Gogh to Holiday and Bruce. One wall featured a layout of her Homage to Picasso series, each work a saturated color-copy photocollage adhered to a small canvas. Conversely, on another wall hung graphite drawings on black-and-white Xeroxes of a heterosexual couple in different sexual positions, the Erotica Drawing series (c. 1977). To these explicit yet clinical illustrations from a sex manual, Steckel added pencil drawings of female faces and nudes, layering them with a sense of memory, experience, and sensuality. The serial installations throughout the gallery created expansive and colorful grids, most comprised of letter- or legal-sized paper, across the gallery’s white walls. The sheer number of works (she advertised hundreds) demonstrates both her commitment to the concept and the function of the copy machine.

The zenith of the exhibition was a mural-sized canvas that could be read, in this context, as the fullest expression of Steckel’s identity as an artist (fig. 14). One of her New York Skyline series (1970–80), Collage (c. 1975–77) is an approximately six-by-nine-foot canvas silkscreened with a found photograph of the city that she covered with a mixed-media spectacle of colorful imagery, including multiple fragments of color photocopies. She described the meaning of her repeated use of the New York skyline in Ms.: “I use the ‘cityscape’ because it’s a visual symbol of male power. . . . The city was built by men and run by men, and its profile can be seen as phallic—all those erect, hard structures.”20 Heavily layered with collaged elements, Collage includes numerous art-historical references as well as appropriated pictures of celebrities with whom she felt kinship. In a prominent place in the center of the canvas lies a photo of Bruce overtop Christ’s face in Leonardo’s Last Supper. She often reworked Catholic symbolism into allegories of modern-day persecution, such as this representation of Bruce, who was arrested for obscenity on multiple occasions and became an anticensorship icon for Steckel. She then framed this collage with representations of two rebellious acts against capitalism—cutouts of photos of graffiti and dollar bills Xeroxed in bright yellow, green, red, and magenta. To the left, another Mona Lisa reproduction with one breast exposed holds an actual paintbrush affixed to the canvas. Steckel has painted in a nude body for her from the waist down, challenging the viewer to accept this hybrid image of female nude and artist standing confidently astride the city’s phallic structure.

The significance of Steckel’s statement was recognized by her feminist peers in the late 1970s. In October 1977, Semmel included a version of Steckel’s Creation Revisited in the show Contemporary Women: Consciousness and Content at the Brooklyn Museum of Art School. The exhibition ran concurrently with the touring historical show Women Artists: 1550–1950, curated by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, which in its scope necessarily excluded contemporary art.21 Semmel selected artists active in the feminist movement and whose work reflected “four thematic ideas which occur with uncommon frequency in women’s art: sexual imagery, both abstract and figurative; autobiography and self-image; the celebration of devalued subject matter and media that have been traditionally relegated to women; and anthropomorphic or natural forms.”22 This Creation Revisited iteration consists of a grid of twenty-four Xeroxes on canvas, the top three rows printed in a bright combination of red and yellow hues, contrasting with the black-and-white copies below. The work encapsulates Semmel’s first two themes with sexual and autobiographical imagery, and, I would argue, Steckel’s use of repetition via the Xerox machine can likewise be viewed as a feminist strategy, exploiting another “devalued media” and method.

In a 1977 article in Chrysalis, art historian Ruth Iskin highlighted Steckel’s use of collage as a feminist statement, noting, “Collage provides Steckel with a means of addressing and using available (male) traditions of culture while giving them a feminist twist.”23 As the longer history of photocollage attests, it could be a productive method for rearranging mass media and consumer culture to expose ideologies and create political statements. Not only does photocollage create a space for inserting an oppositional feminist voice, as Iskin suggests of Steckel’s addition of herself into the pictures, but with the use of xerography, Steckel also played with the intersections of replication and creativity. She paradoxically borrowed and repeated images from her own body of work alongside that of canonical artists to assert her identity as a fine artist.

Steckel made numerous versions of artworks by rephotographing or photocopying images and reworking them into what she called “new originals,” a practice in direct defiance of the art market and museum systems that rely on the value of “unique” artworks. Her use of copying processes pushes against the need to authenticate an original while exposing the tie between art and commerce, the collapse of which her rainbow-colored stack of dollar bills suggests. More broadly, her practice challenges the persistence of modernist ideals of authenticity and originality that underpin the art market and perpetuate exclusionary notions of creativity. Steckel adeptly manipulated found imagery to call out these inequities and to insert herself into a history of art from which she felt women had been erased. Yet she made her appropriation of that history the subject of her work by using mass-produced reproductions, mere copies that circulate as signifiers of the male artists’ achievements. She then redoubled her critique by creating series of bold and colorful copies with a Xerox machine, repeatedly picturing herself as the image of an artist.

Cite this article: Rachel Middleman, “Self-Portraits and Photocopies: Anita Steckel’s Feminist Collage,” in “Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist,” In the Round, ed. Ellery E. Foutch, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17516.

Notes

- Patrick Firpo, Lester Alexander, and Claudia Katayanagi, Copy Art: The First Complete Guide to the Copy Machine (New York: Richard Marek, 1978), 7. ↵

- Anita Steckel, “Kind Lady” (letter to the editor), Esquire, December 1963, 16. ↵

- Miriam Schapiro, “Femmage,” in Collage: Critical Views, ed. Katherine Hoffman (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989), 295–315. Also see Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics 1, no. 4 (Winter 1977–78): 6–71. ↵

- Marcel Duchamp, “Dada,” interview with Herbert Crehan, Evidence 3 (Fall 1961): 37. ↵

- Dale Lewis, “Anita Steckel,” New York Free Press, 1969; Al Brunelle, “Anita Steckel,” ARTnews, March 1969, 69. Both articles are clippings in the Anita Steckel papers, Archives of Women Artists, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, Washington, DC. ↵

- See Rachel Middleman, Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018). ↵

- “Male Nudes Shown,” Village Voice, March 30, 1972. ↵

- “Who, What, Where: Feminist Art,” Journal-News, February 5, 1972, 6. Clipping in the Anita Steckel papers. ↵

- Although absent from the first Fight Censorship meeting in Steckel’s studio on March 8, 1973, Judith Bernstein and Barbara Nessim also participated in the group. ↵

- For more on the male body in feminist art and the Fight Censorship group, see Richard Meyer, “Hard Targets: Male Bodies, Feminist Art, and the Force of Censorship in the 1970s,” in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Cornelia Butler et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 362–83. ↵

- On Michael C. Luckman’s course at the New School for Social Research and the Fight Censorship group, see Alison Gingeras, “Anita Steckel and the Fight Censorship Group: ‘The Golden Age of Porn’ Meets Feminist Art,” in Anita Steckel: The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics, ed. Richard Meyer and Rachel Middleman (Stanford, CA: Stanford Art Gallery, 2022). ↵

- Anita Steckel, September 1977. Anita Steckel Estate. ↵

- Firpo, Alexander, and Katayanagi, Copy Art, 104. ↵

- On this history, see, for example, Marsha Meskimmon, The Art of Reflection: Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996). ↵

- Firpo, Alexander, and Katayanagi, Copy Art, 7. ↵

- The recent symposium “Xerography: Women Artists, 1965–1990,” held at the Institut national de’histoire de l’art in November 2021, aimed to address this lack of in-depth study and will hopefully result in a new wave of scholarship. Also see Maymanah Farhat and Jennie Hinchcliff, Positively Charged: Copier Art in the Bay Area since the 1960s (San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Center for the Book and San Francisco Public Library, 2023). For a cultural history of xerography, see Kate Eichhorn, Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016). ↵

- Erica X. Eisen, “The Work of Art in the Age of Xerox Reproduction,” Lady Science, July 1, 2018, https://www.ladyscience.com/the-work-of-art-in-the-age-of-xerox-reproduction/no47. ↵

- Firpo, Alexander, and Katayanagi, Copy Art, 105. ↵

- Anita Steckel, interview with author, January 2007. ↵

- Catherine Houck, “Women Artists Today,” Ms., January 1980, 258. ↵

- Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550–1950 (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976). ↵

- Joan Semmel, Contemporary Women: Consciousness and Content, October 1–27, 1977, exhibition announcement poster, 1977. ↵

- Ruth Iskin, “Anita Steckel’s Feminist Fantasy: The Making of a New Ideology,” Chrysalis 3 (1977): 93. ↵

About the Author(s): Rachel Middleman is Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Art History, California State University, Chico.