Arabian Nights in the Mississippi Delta: The Embroideries of Ethel Wright Mohamed

Embroiderer Ethel Wright Mohamed (1906–1992) was many things: the proud wife of a Syrian immigrant, a mother of eight, an entrepreneur, and a philanthropist. Born and raised in Mississippi, Ethel, a white Baptist woman, met Hassan, a Syrian Muslim man, in 1923. He was the love of her life. As the family tells the story, Hassan came to the bakery Ethel worked at in Shaw, Mississippi, every day. One day, Ethel quipped he must really like bread. Hassan responded he really liked her. The two wed in April of 1924, raised their family in Belzoni, Mississippi, and were married forty-one years.1 Mississippi and Hassan are the threads tying together Ethel’s biography and embroideries, which were inspired by her memories.

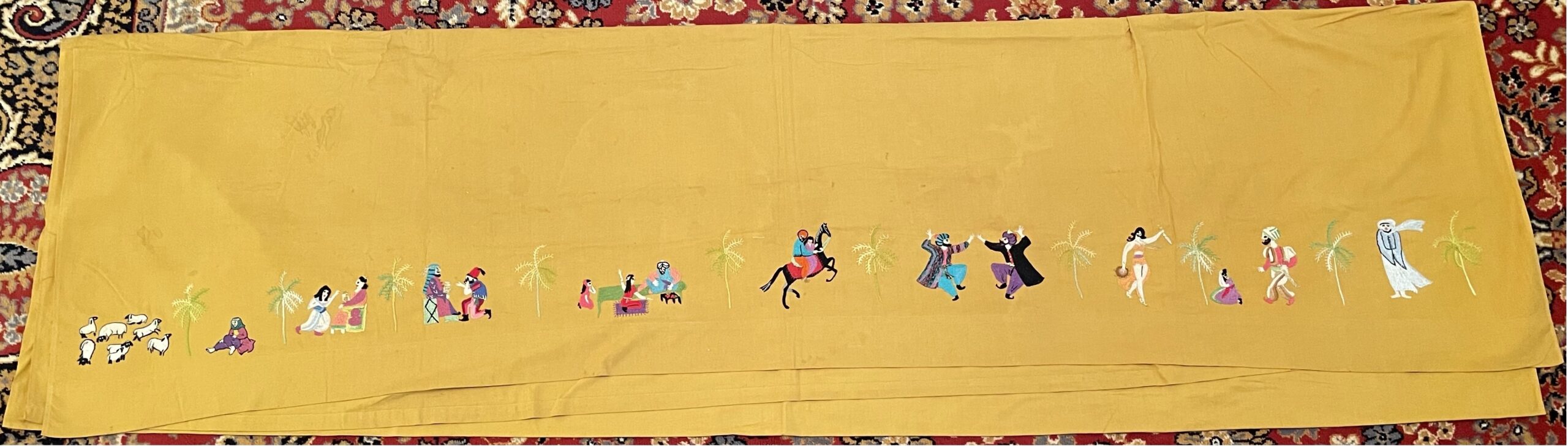

In a flat sheet titled Arabian Nights (1964), Ethel makes visible the global and local dynamics shaping her embroideries. Stitched on gold fabric, ten vignettes are separated by barren date trees embroidered in shades of green to imply the moving sun and passing day (fig. 1). The vignettes appear side by side, like illustrations in a book. She depicts wandering sheep, lone individuals, people prostrating themselves, gift giving, men dancing, a woman with a tambourine, a rearing steed, and two girls listening. Her characters have limited facial expressions, perhaps due to the thick thread. Instead, distinct personalities come alive through vibrantly colored clothing stitched in blocks. These characters are oriented so the sheet’s user could see them.

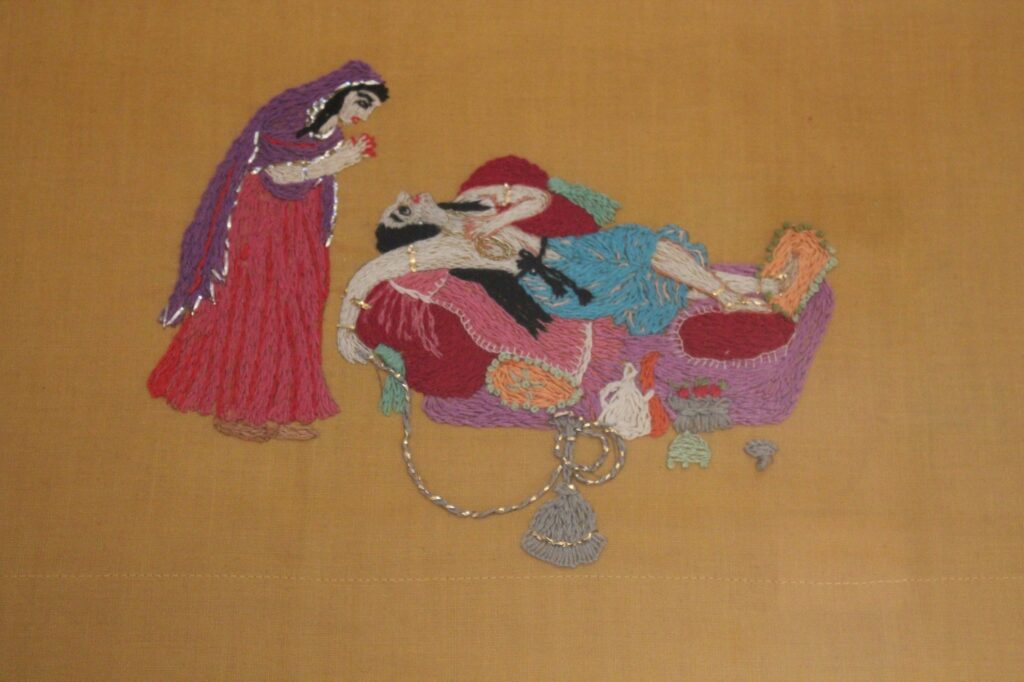

Two gold pillowcases accompany the flat sheet. The first depicts a supine woman wearing aqua blue pants, languishing on a chaise, holding her pipe. Another woman, dressed in a pink dress with a lilac veil and distinguished by her rose-red nails and lipstick, stands over her (fig. 2). Each stitch, comprised of thick thread, forms a lined portrait akin to etching. The second pillowcase depicts two men seated by a gameboard, enjoying their pipes while surrounded by date trees (fig. 3). Two small brown cows and two saddled horses overlap with the foliage, suggesting they are tied to the trees. The green and red dots below the board are colored game pieces. Individual stitches are visible yet continuous, making the folds of the clothing echo the fabric. The two women and date trees are repeated, unifying motifs throughout the scenes.

Across the set, Ethel references two places significant to her family: Mississippi and Lebanon. The gold-ground fabric was found in Mississippi and repurposed, embedding the object in the Delta. The date trees, native to the Middle East, allude to Hassan’s family home in Lebanon. Ethel would likely have seen date trees when she traveled with Hassan in 1949 to celebrate their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. The two went on a six-month journey from Mississippi to Saraain, Lebanon, which was the first time Hassan returned home after emigrating. The trip was Ethel’s idea, to relieve Hassan’s homesickness, but it also offered her new insight into Hassan’s life. In her journal, Ethel wrote about seeing Damascus as an “Arabian Nights dream,” yet there was no place she and Hassan would rather be than home in Mississippi.2 When they returned, the two regaled their children with tales of their world travels. The date trees frame each scene while standing in for the confluence of factors shaping Ethel’s rendering of The Arabian Nights: Hassan’s home, the foliage described in the book, Ethel’s memories of home and abroad, and their shared role as storytellers. But what do representations of The Arabian Nights, a compilation of tales from the Middle East, in the work of a little-known Mississippi embroiderer tell us about midcentury Mississippi, immigration, family, and home? And how is this complicated by the state’s history as a home for Arab immigrants and a site of racial terror in the twentieth century?

Through oral histories with the Mohamed family and archival findings, I argue that Ethel’s Arabian Nights is a hybrid between a documentation of memory, a reinterpretation of stories, and a material embodiment of the potentialities of life in the Mississippi Delta. Ethel’s stitchery shows the way Hassan retained and transmitted his Syrian background through storytelling, a process Ethel recalls through craft. Scenes from The Arabian Nights embroidered onto found fabric are imbued with a local, personal significance, reflecting the ways Hassan’s culture took new forms in the Delta diaspora. Ethel aimed to preserve Hassan’s culture and their family histories after their deaths through embroidery, rendering the object a conduit for telling a story about Ethel and Hassan’s experiences making a home for their interconfessional, intercultural family in the Mississippi Delta. In turn, I begin to parse the contradictions between the paradisiacal utopia Ethel envisioned in her Arabian Nights as she reflected on intimate family moments and the violent racial realities of the Jim Crow South.

I therefore resituate Ethel’s Arabian Nights within the Delta through a multilayered reading that is attentive to memory, history, storytelling, interpretation, and their dissonances. While one impulse might be to read these scenes as literal illustrations, the original tales should be understood as a framework for interpretation. By framework, I mean that Ethel’s embroideries are not one-to-one reproductions, but metonyms for recurring characters, tropes, and systems of meaning. Hassan was illiterate and could not read to his children from books. Instead, he retold tales he likely heard from family and friends. As such, there is a sense of ambiguity between Hassan’s storytelling as source material, Ethel’s visual interpretation, her creative liberties, and the way audiences see the embroideries today. The Arabian Nights is also not one standard text, but a compilation that evolved throughout the twentieth century, shaped by European writers. A metonymic reading similarly accounts for key features of Ethel’s embroideries, such as the way her work documents her memories, explores her family history, and teaches lessons through moralizing tales.3 Ethel did not explain what her Arabian Nights meant, which further opens up the possibility of different literary, personal, local, and global readings. For these reasons, Ethel’s Arabian Nights should be reconceptualized as an episode of storytelling about one family who made their own “Arabian Nights” in their Mississippi Delta home and about Ethel’s memories thereof as they evoke fantasy, imagination, and nostalgia.

Fabricating the Arabian Nights

One particular scene illustrates the embroidered set’s narrative structure, uncovering the way the fabric became a site for place and mythmaking, constructed through Ethel’s needle, while uncovering her view of both past and present. Located left of center on the flat sheet, a vignette features two attentive young girls sitting on the floor next to a man lying on a chaise wearing a multicolored outfit (fig. 4). The nearby table abounds with ripe, cherry-red dates with stems of petite green foliage. The young girl to the left wears a pink dress, each thread of which is visible. Her unique attire alludes to her identity and personality as someone distinct from those around her. She rests her head in her hand, her elbow close to the chair, as if she is holding herself up. The girl kneeling closest to the man is depicted with more detail. She is clad in a vibrant red dress (the same color as the dates), a gold belt, and bracelets along her arms. Ethel shows her seated on a purple rug with arms outstretched, as if eagerly reacting to the moment. Ethel frames this scene with two date trees whose tonalities evoke the sun’s shifting rays while separating this moment from other vignettes.

The simplistic figural rendering conflates two moments of storytelling, interweaving The Arabian Nights and life in the Mississippi Delta. As cued by the work’s title, Ethel presents her vision of a scene from The Arabian Nights that alludes to the tales’ premise. In The Arabian Nights, the protagonist is Shahrazad, a young girl who tells stories to King Shahryar to save herself and other women from the violence he enacted on his wives. Shahrazad’s request, as she seemingly embarked upon a path to her own death, was that her sister, Dunyazad, be permitted to spend Shahrazad’s last night with her. The king obliged, and Dunyazad watched her sister’s narrations.4 Each night, Shahrazad’s tales captivated the king, so he did not kill her; in this way, she saved herself and many others. What was expected to last a few nights went on for one thousand and one nights, hence the book’s alternate title. In Ethel’s embroidery, Shahrazad is likely the girl in red, and Dunyazad in pink.

On one of the pillowcases, Ethel portrays a similar scene of two women (see fig. 2). One appears in a bright pink dress and watches over another woman in blue pants, who reclines with her pipe. Hassan used this pillowcase, which is now framed and hangs in Ethel’s bedroom. On the back of the frame, Ethel wrote, “Schezerade [sic], Arabian Nights.” This is the only instance in this embroidered set where Ethel described her subject, which, along with the similarities between the two girls across the sheet and pillowcase, confirms that Shahrazad and Dunyazad are indeed pictured.

The Arabian Nights has a dual significance related to Hassan’s biography and the Mohamed home in Belzoni. Hassan was an avid storyteller who relayed tales from The Arabian Nights to his children.5 While the family recalls some of these stories, many are unknown, and Ethel did not write all of them down. Instead, Ethel embroidered pictures summarizing Hassan’s storytelling, revealing the way she remembered these family moments. As such, the vignette on the sheet can also be read as Hassan telling stories while his daughters listen, an act that occurred daily in their home (see fig. 4).

Understanding this scene as an intimate family moment imbues a global narrative with local significance, complicating ideas of storytelling, narration, and tradition. Hassan is the narrator just as much as Shahrazad. Shahrazad and Hassan merge as they both tell stories to prolong their lives. Shahrazad tells tales to ensure her survival, while Hassan narrates anecdotes from his life and other tales to create family memories that will carry on his legacy in his adopted homeland. Ethel’s embroidery visually documents the interplay between factual happenings and fictional tales permeated by a longing to return to these family moments. Such slippages between narrator, protagonist, and character allow Ethel to tether The Arabian Nights to the Mississippi Delta.

As its creator, Ethel condenses complex narratives and histories into a concise picture, positioning herself as narrator. She selects and orders stories in the same manner as Hassan, a process complicated by witness, memory, and fantasy. Ethel depicts her happy recollections of witnessing Hassan’s storytelling. She stitches what she remembers, blurring fact and fiction, reality and fantasy, positioning Hassan as the protagonist and Shahrazad as another character, while overlooking unhappy moments. In hindsight, knowing that she watched Hassan’s health continue to deteriorate while she embroidered, her fabrics also reveal a nostalgic fantasy for a bygone time of health and happiness. By visualizing these overlapping narratives, Ethel extends her life as the holder of memories, creating a record of the way she saw her home, family, and life in the Delta while reflecting on the way Hassan’s Syrian heritage shaped her environment and experiences.

The process by which Ethel constructed stories in her embroideries parallels the way The Arabian Nights was also fabricated over time. As Dwight Reynolds explains, there are fragments of The Arabian Nights dating to early ninth-century Syria, as well as tenth-century accounts of the story in Arabic literature.6 Early editions, however, likely only contained two to three hundred nights of storytelling. The manuscript’s transformation into one thousand and one nights results from Antoine Galland, the text’s translator, who may have taken creative liberties by adding or editing stories.7 Tales from The Arabian Nights are frequently adopted, adapted, and extrapolated upon, a historical malleability that echoes the way Ethel selected, edited, and visualized her memories in images, invoking the carefully fabricated nature of both images and stories.

Just as The Arabian Nights incited fantasies about the Middle East, so too did Ethel’s interpretation. Ethel explains in her journals that, at the time of the work’s making, Hassan was sick, and since he often felt bad, she wanted to make him smile by reminding him of his home.8 She chose The Arabian Nights to remind Hassan of Lebanon and his Syrian background. The text becomes a metonym for Hassan’s culture, and the collection of folktales represents the history of storytelling in the Middle East. The fabric also becomes a means to invoke the book’s broader themes. Gold frequently appears in The Arabian Nights as an object of exchange or ornament. Gold also references Ethel’s memory and her world travels with Hassan; when she went to Florence with Hassan on her way to Lebanon, she wrote about how much she loved the gold on the art.9 Laying the sheet on Hassan’s bed was also significant: his bed was one of the first things he owned after arriving in Mississippi. He took it with him when he moved, a tangible sign of his success.10 The sheets and the bed draw together what was most important to Hassan: his family, his home, and his culture. While Ethel recalls her journey to the Middle East and Hassan’s storytelling through the sheet, its location on Hassan’s bed literally and metaphorically returns the narrative to their Mississippi home, intertwining their life experiences into one object.

The amorphous, fluid nature of The Arabian Nights was the perfect vessel for Ethel to overlay her reminiscences of life in Mississippi. The work was about her memory of Hassan telling stories, family time, world travels, and the fantasy of a better era. In a manner similar to the way the original tales romanticized an imaginary world, Ethel projects a fantasy of a peaceful, jovial Mississippi. In this way, historical factors, such as the European transformation of The Arabian Nights and violent segregation in the South, faded in favor of more rosy memories. Just as the one thousand and one nights portray a homogenous notion of the Middle East, Ethel’s interpretation of Syrian culture condenses a complex history and region into an act of storytelling to illuminate her point of view. Arabian Nights comes to represent what Hassan brought to Mississippi, a culture that became local, close, and familiar to Ethel. By using a needle and thread on remnant fabric, Ethel captured subjective emotions and sentiments, things that were fleeting, intangible, and affective, now given material form through embroidery.

Re-Fabricating the Arabian Nights

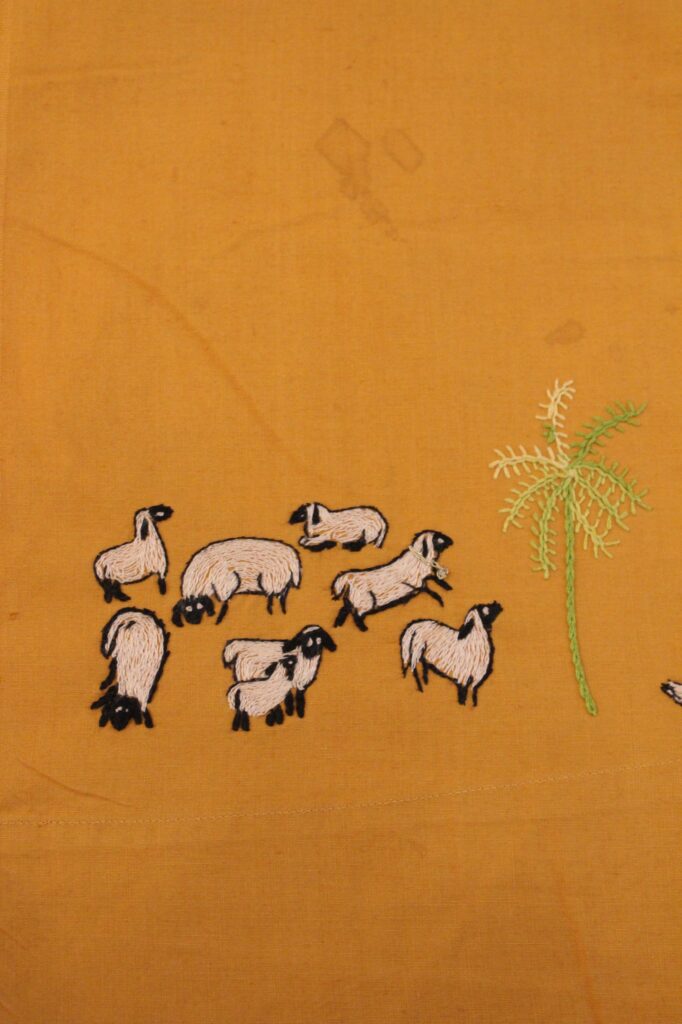

The first vignette on the bedsheet brings together Hassan’s Syrian culture and the Mississippi home he and Ethel shared while eliding other histories. Ethel depicts eight wandering sheep against a landscape of date trees (fig. 5). She outlines their bodies in black and flattens the wool into straight lines of thick white stitches. Next to the flock, a figure rests alone under a tree similarly colored in shades of white, yellow, and green to imply the sun’s movements (fig. 6). The figure’s vibrant attire echoes the overarching palette: a turquoise head covering, a bright pink robe, and purple pants. The body shape and coarse facial features obfuscate the character’s gender; however, the lack of visible hair suggests the figure is a man.

Sheep appear throughout The Arabian Nights, described as sustenance, referenced when shepherds guard their flocks, or killed as gifts. Likewise, individuals frequently wander open landscapes, such as in a story about a wealthy merchant who rests under a tree. By depicting common motifs from The Arabian Nights, Ethel designs open-ended narratives. The sheep and the man also relate to Hassan’s life. Hassan’s family in Saraain tended sheep, making these animals a reference to those he loved and missed.11 Ethel also points to her eight children, each of whom had a “Syrian” middle name.12 Just as caretakers watch over their sheep in The Arabian Nights, Hassan tended to his children. Ethel’s stitches transform the sheep from animals into symbols for family, near and far.

The lone man can also be seen as Hassan, who arrived at Ellis Island in 1911 from Saraain, a small village in Lebanon, ninety minutes from Beirut near the Syrian border.13 Hassan is sometimes described as Lebanese, perhaps because Saraain is in today’s Lebanon, yet he called himself Syrian, and the family reaffirms this identification.14 Hassan did not speak English when he emigrated. After arriving in the United States, he worked as a peddler, selling whatever he could to survive in New York, then in Clarksdale and Shaw, Mississippi.15 Hassan moved south in pursuit of economic opportunities, stopping to rest under the shade of trees during his travels. Ethel frequently described his journey orally and visually. Through her embroidery, Ethel fused the lone man from The Arabian Nights with Hassan’s peripatetic early life in the United States.

Ethel described Hassan’s immigration story as a search for the “American Dream,” an opportunity to prosper and obtain a better life.16 His decision followed the path of many Arab immigrants who settled in the US South beginning in the late nineteenth century.17 Arab populations in Mississippi divested from cotton in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, instead ensuring their livelihoods as peddlers, and later, store owners.18 The earliest Arab peddlers in the South traveled and sold goods to Black and white farm families. While the exact number of Arab peddlers is unknown, they were often the only ones to offer credit to Black families and continued to do so when they opened stores beginning in 1908.19 By selling across the color line, despite segregationist laws, these merchants—including Hassan, and after his death, Ethel—both relied on Black customers and upheld fair practices while white-owned stores remained segregated.20

In the United States, Arab populations occupied a precarious racial position somewhere between white and non-white, which allowed them to traverse Black and white spaces. While Arab peddlers thrived economically in the Jim Crow South, they had to navigate shifting racial boundaries carefully. James G. Thomas Jr. describes the region as a “caste-based, Jim Crow Delta,” where the ambiguous racialization of Arab residents invoked an uncertainty that was formative to their economic opportunities.21 The US Naturalization Act of 1790 made American citizenship contingent on whiteness.22 The cases of Ex Parte Dow (1914), In re Dow (1914), and Dow v. United States (1915) designated Syrians as white in contrast to the non-whiteness of Iranians.23 Notably, this excluded Muslims until 1944 with the court decision Ex Parte Mohriez.24 These court cases, among others, indicate the ways shifting legal consensuses constructed and affirmed racial hierarchies that likely affected Hassan’s movement throughout the segregated South.

While Hassan and Ethel did not document their perceptions about the way race shaped lived experience, the legalized white racialization of Syrians, like Hassan, afforded him certain privileges. For example, Hassan’s contingent racial status allowed him to marry Ethel and build a life in Mississippi despite the prevalence and impact of miscegenation laws. The US Supreme Court did not rule against state laws that made interracial marriage unconstitutional until 1966. In Mississippi, voters did not repeal the state constitution’s 1890 ban on interracial marriage until November 3, 1987. Whiteness made Ethel and Hassan’s life in the Delta possible, even as their lives were affected by the continual renegotiation of racialization. While their marriage was uncommon, there is no evidence indicating that they discussed leaving Mississippi, suggesting it was their chosen home for their family.25 Ethel’s position as a white woman also afforded her the privilege to move freely in the South and likely offered Hassan some additional sense of safety.

While Hassan gained the legal privilege of whiteness soon after arriving in the United States, his religion complicated this status. Legal rulings around whiteness excluded Muslims, meaning Hassan’s position was contingent on him not mentioning that he was Muslim. He did so only intermittently. For example, Hassan courted Ethel through conversations with her father, a Baptist preacher, in which Hassan told him about being Muslim and his home in Lebanon.26 During their marriage, Ethel attended the nearby Baptist church, and Hassan remained a practicing Muslim. He could not read the Qur’an, but he knew its contents. Every week, Ethel summarized the Baptist sermon, and Hassan offered a Qur’anic parallel in return.27 Ethel’s journals, however, do not record the nuances of navigating an interconfessional, intercultural marriage in the Jim Crow era or what tensions may have emerged.

While Hassan safely and prosperously maneuvered the racial politics of the Delta, not all Arab peddlers were exempt from racial violence. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) reports that between 1882 and 1968, 4,743 lynchings occurred in the United States. Of these, 581 occurred in Mississippi alone, the highest number during that period.28 In 1885, an Arab peddler in Mississippi was nearly lynched over a misunderstanding; his life was saved when another Lebanese peddler intervened.29 By the 1950s, retaliations against the momentum of the Civil Rights Movement brought renewed violence to the region.30 In 1955, fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was lynched roughly forty-five miles away from the Mohamed home where Ethel tended to her eight children and supported Hassan while he managed his dry-goods store. Such violence was informed by white supremacy, anti-Black racism, and xenophobia, all occurring within Hassan’s mercantile terrain. While no instances of physical violence against Hassan are recorded in Ethel’s journals or embroideries, it does not mean that Hassan never experienced discrimination, harassment, or negative ramifications for being Arab in the Delta. Personal histories related to the interstices between his legal racial status and lived experience are yet to be uncovered.

The white thread Ethel used for the lone figure’s body, then, suggests more than a metonym for Hassan’s identity (see fig. 6). Rather, the color acts as a metaphor for the racial, legal, and social hierarchies that shaped Hassan’s life in the Delta. White also indicates one aspect of Hassan’s way of being in the world as a Syrian Muslim man in relation to Ethel’s white Southern Baptist identity. His contingent whiteness enabled them to have their life in the Mississippi Delta. In her embroideries, Ethel represents her perspective of the Delta as a convivial region and the ideal place for their family, where Hassan could be Muslim and share his Syrian heritage. The utopia Ethel remembers contradicts the way history understands the region, conveying a fantasy of the Delta as liberated from economic depression, segregation, racism, and violence, an alternative world materialized from her memories.

Fabricating a Story Now

Located in the Mohamed family’s home, Mama’s Dream World: The Ethel Wright Mohamed Stitchery Museum in Belzoni, Mississippi, now preserves Ethel’s idealistic version of Mississippi history by highlighting the way Ethel and Hassan saw the Delta as an enclave of intercultural acceptance and fiscal prosperity, despite the racial violence of the Jim Crow era. The pillowcase of Shahrazad and Dunyazad is displayed there (see fig. 2) along with another pillowcase made in 1965 titled Arabs (4 Men Smoking Pipes) (fig. 7), located in Hassan’s bedroom, where he spent his final days. Both are typical of Ethel’s colorful, imaginative pictures inspired by her memories and perspective about the world. The museum, which Ethel played a role in founding in the late 1970s with her children before her passing in 1992, positions Ethel as the ultimate narrator and storyteller. By hanging these works in a museum dedicated to her, Ethel shapes the family story and legacy for the public.

Through stories and stitcheries, Ethel shares her knowledge and interpretations of Hassan’s culture and memories about life in the Delta. Hassan’s culture and her knowledge of The Arabian Nights also became key elements of later work, such as The Mosque (1971), The Late Lunch (n.d.), The Ancient Hunter (1975), and The Beautiful Horse (1978–79). Through imagery related to the Arab world, Ethel adopts a role as carrier of Hassan’s culture after his death. Her craft is a means to outline and share what Hassan brought to Mississippi from Lebanon and explain to others how aspects of his culture took new form in the Delta. Her choice to adopt and adapt what she saw as Arab iconography did not prompt questions of positionality but was seen as an effort to pass on family history.

As tales from abroad told in the Mississippi Delta, Ethel’s embroidered Arabian Nights exposes a complex interplay between stories and recollections, and the intersection of the local and the global. Ethel’s stitches do more than document her memories or illustrate a historical tale from the Middle East. By stitching these stories onto something Hassan held in his final months, the people and experiences he valued most were given a material proxy in an ode to his homeland, the couple’s travels, and the stories he told their children. Ethel’s fabrics bound together body and memory, stitching the many threads of their life into something he cherished before his passing. Through her carefully embroidered scenes, Ethel wove together a world between Lebanon and Mississippi, linking a global story and local memory. While reflecting on the past, Ethel similarly imagined a happy, prosperous, and violence-free future for her children and grandchildren. Such a rereading of Ethel’s embroideries results from reconsidering the confluence of factors shaping the creations of a global, cosmopolitan woman like Ethel and envisioning the ways the global takes root in unexpected places.

Cite this article: Rachel Winter, “Arabian Nights in the Mississippi Delta: The Embroideries of Ethel Wright Mohamed,” in “Art History and the Local,” In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13227.

Notes

This research was supported by a Craft Research Fund grant from the Center for Craft.

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author, Belzoni, Mississippi, May 2021. The Mississippi Delta, or Yazoo-Mississippi Delta, is a region in northwest Mississippi between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, encompassing cities like Belzoni, Clarksdale, Indianola, Shaw, and Yazoo City. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author; Ethel Wright Mohamed’s journals, The Ethel Wright Mohamed Stitchery Museum, Belzoni, Mississippi; hereafter Mohamed’s journals. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author; Mohamed’s journals. ↵

- The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights, trans. Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons (London: Penguin, 2010), preface to night 1. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author. Ethel wrote about some of Hassan’s stories, such as “Girl with the Iron Hand,” “The Magic Horse,” “The Man in the Net,” and “The Late Lunch.” See William R. Ferris, Local Color: A Sense of Place in Folk Art (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982), 120. ↵

- Dwight F. Reynolds, “A Thousand and One Nights: A History of the Text and Its Reception,” in Arabic Literature in the Post-Classical Period, ed. Roger Allen and D. S. Richards (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 270–71. ↵

- Reynolds, “A Thousand and One Nights,” 272–78. ↵

- Mohamed’s journals. ↵

- Mohamed’s journals. ↵

- Mohamed’s journals. ↵

- Ferris, Local Color, 105. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author. For a list of these names, see Joseph Schechla, “The Mohameds in Mississippi,” in Taking Root: Arab-American Community Studies, ed. Eric Hooglund (Washington, DC: American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, 1985), 2:59–68. ↵

- Schechla, “The Mohameds in Mississippi,” 2:60–61. Hassan’s immigration record can be found on the Ellis Island Foundation website. When Hassan emigrated, he left a territory of the Ottoman Empire, now in Lebanon, which was formerly a province of Ottoman Syria. See Carl L. Bankston III, “The International Immigrants of Mississippi: An Overview,” in Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi: The Twentieth Century, ed. Shana Walton and Barbara Carpenter (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 26. Bankston adds that many Syrians were misclassified as Lebanese. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author. For instances where Hassan is erroneously described as Lebanese, see Charlotte Capers and Olivia P. Collins, eds., My Life in Pictures: Ethel Wright Mohamed (Jackson: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 1976). ↵

- Capers and Collins, My Life in Pictures. For a more thorough account of Hassan’s immigration and an alternative history of the Mohamed’s life in Mississippi, see Schechla, “The Mohameds in Mississippi.” ↵

- Ethel Wright Mohamed, “An Oral History of Southern Agriculture,” National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 1987. ↵

- Bankston, “The International Immigrants of Mississippi,” 22, 26; Stacy Fahrenthold, Between the Ottomans and the Entente: The First World War in the Syrian and Lebanese Diaspora, 1908–1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 14–22. Here, “Arab” encompasses Lebanese and Syrian populations. ↵

- Fahrenthold, Between the Ottomans and the Entente, 26; James Thomas, “Mississippi Mahjar: The Lebanese Immigration Experience in the Delta,” in Walton and Carpenter, Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi, 174. ↵

- Thomas, “Mississippi Mahjar,” 173–77, 184. ↵

- Thomas, “Mississippi Mahjar,” 178–82; Shana Walton, “Introduction: Ethnicity in Mississippi; Stories Worth Telling,” in Walton and Carpenter, Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi, 4. ↵

- Thomas, “Mississippi Mahjar,” 172–83; Walton, “Introduction,” 3–4. ↵

- Neda Maghbouleh, The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017), 17. For a more thorough description of these rulings beyond Maghbouleh, see Fahrenthold, Between the Ottomans and the Entente; Sarah M. A. Gualtieri, Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009). ↵

- Maghbouleh, The Limits of Whiteness, 17–18. ↵

- Immigration quotas remained for Muslims until 1952. ↵

- Thomas, “Mississippi Mahjar,” 185. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author. ↵

- The Mohamed family, conversation with the author. Ethel also gained knowledge about Islam and other religions by copying the encyclopedia. ↵

- William I. Hair and Amy Louise Wood, “Lynching and Racial Violence,” in The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. Thomas C. Holt, Laurie B. Green, and Charles Reagan Wilson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 24:89; Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 3, 261; “History of Lynching in America,” NAACP, accessed March 1, 2022, https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-america. ↵

- Terence Finnegan, “Lynching and Political Power in Mississippi and South Carolina,” in Under Sentence of Death: Lynching in the South, ed. W. Fitzhugh Brundage (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 194. ↵

- Stephen A. Berrey, The Jim Crow Routine: Everyday Performances of Race, Civil Rights, and Segregation in Mississippi (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 141; Yasuhiro Katagiri, Black Freedom, White Resistance, and Red Menace: Civil Rights and Anticommunism in the Jim Crow South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014), 185. ↵

About the Author(s): Rachel Winter is Assistant Curator at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University.