Note to Self: An Artist’s Reflections on Black Girlhood

In the wake of the US Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, rights to bodily autonomy and self-possession seem ever more precarious for women and girls—Black women and girls in particular. Encroachment upon the liberties of women and girls is not a new subject of art making; however, I am intrigued by modes of reclamation that Black women artists have harnessed through memory work that centers on girlhood and, by extension, motherhood. In the face of dispossession, in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson and beyond, Black women artists have consistently found ways to restore themselves, often through a return to their youth.

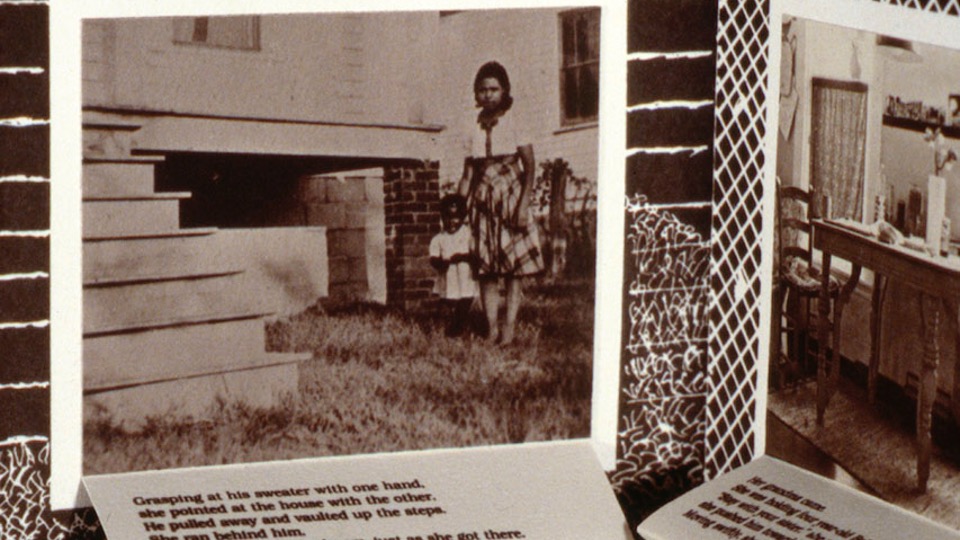

Artist Clarissa Sligh returned to the space of her childhood for artistic inspiration and healing. For months, Sligh pored over family snapshots, finding pieces of herself long buried. Cutting, pasting, and annotating family photographs, Sligh began her practice as a visual griot and quotidian archivist out of a desire—truly, a necessity—to reclaim her youth and past from the clutches of time. In her prints, books, and installation works, Sligh repossesses her body, her memories, and her truths through a literal reconfiguration of remnants from her past. The resulting works, including Sligh’s 1988 debut book project, What’s Happening With Momma?, demonstrate the power of world-building from the vantage point of girls—a practice that remains underexamined within the context of Black feminist art histories (fig. 1).

Folding out into the reader’s space, Sligh’s house-shaped accordion book delves into an intimate moment of innocence lost and knowledge gained. The reader enters the interior life of the artist, known to her family as “Skookie,” as she grapples with the birth of her younger sibling. The grisaille-toned photographs evince the wear of time and emblematize faded memories, further crystallized through the handwritten text that cascades down the folded strips of paper that mimic stairs. The dynamic form resembles the suppression of memory. Once compressed and stored away in the recesses of one’s mind, these memories are later allowed to unfold; they are pieced back together through images and narrative.

In recounting the birth of her younger sibling, Sligh privileges Skookie’s vision—we are not merely onlookers, but rather we see the world through her eyes. We enter her world as it is being turned upside down. The lack of direct correlation between image and text evokes jumbled moments, disheveled in the mind, that Sligh continuously attempts to grasp as she moves through her exploration of past experience. Beneath a snapshot of Sligh and her mother (fig. 2), she writes, “Inside the house, her momma’s screams and moans of agony flowed through the walls.” We recognize that we are limited to Skookie’s recollection, and Sligh does not seek to reconcile these gaps with knowledge later acquired. Instead, we are intentionally refused visual entry into the scene of the birth and left to draw our own conclusions. Sligh conjures the world of Skookie and allows us to witness the unease of not knowing and of coming of age. The form of the text embodies the trouble of memory—disjunctive, dwindling, always just beyond our grasp.

In a moment when Black women and girls’ precarious relationship with civic sovereignty is placed front and center in national political discourse, their work, their voices, and their reflections need to be recognized. I focus on What’s Happening with Momma? to engage the memory-work enacted by Sligh and to consider the importance of Black women’s evocations of girlhood through embodied memory. Sligh carries us through a disquieting experience of childbirth that shakes Skookie to her core. Her life is forever transformed, which we come to understand through the final passage, in which Skookie—body and mind worn from the whole ordeal—becomes not only a sister but a mother in her own right. The ending articulates the troubled boundary between girl and woman that often removes girls—especially Black and Brown girls—from the aegis of childhood innocence. What’s Happening with Momma?, as a work of memory and reclamation, elucidates the powerful connection between girlhood and womanhood that scholars of art history must further explore.

Cite this article: Kéla Jackson, “Note to Self: An Artist’s Reflections on Black Girlhood,” in “Art and Reproductive Rights in the Wake of Dobbs v. Jackson,” Colloquium, ed. Keri Watson and Katherine Jentleson, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15285.

About the Author(s): Kéla B. Jackson is a PhD candidate in the History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University