Art, Bananas, Cash: Learning from Banana Craze

PDF: de Laforcade, Art, Bananas, Cash

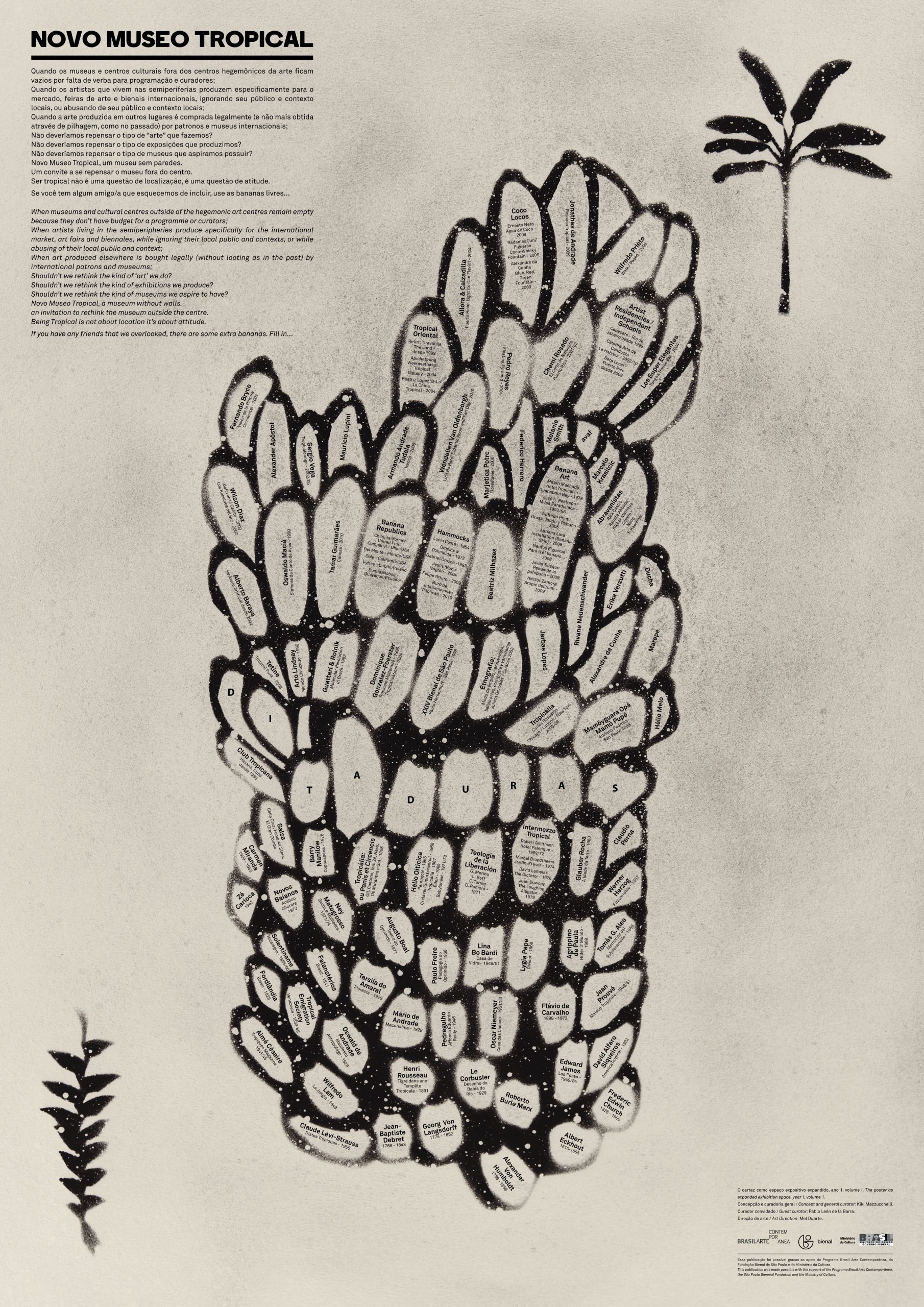

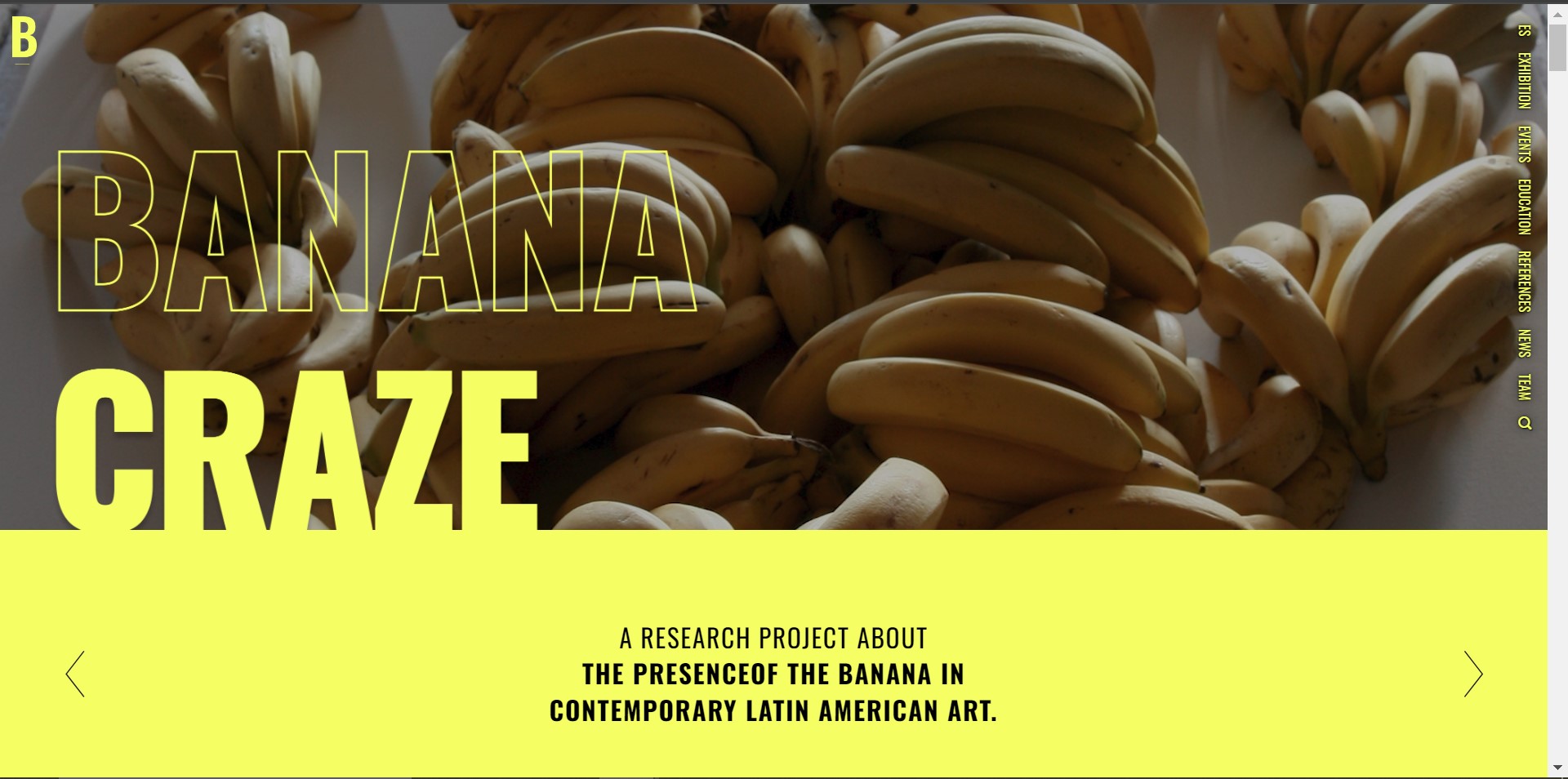

A 2010 diagram by Pablo León de la Barra models the history of art in Latin America on the structure of a banana bunch (fig. 1).1 Banana shapes encircle the names of figures and projects ranging from the seventeenth-century Dutch painter Albert Eckhout to Cuban artist Tania Bruguera’s Cátedra Arte de Conducta (Behavior Art School). The accompanying text invites readers to contribute to the chart by adding missing names to the multidirectional banana clusters. Suggesting the possibility of an ever-expanding rhizome, León de la Barra’s art-historical chart is itself one of almost two hundred works featured in the recent relaunch of Banana Craze, a bilingual digital research project created in 2021 by Juanita Solano and Blanca Serrano, which also takes the banana as a starting point for a hemispheric history of art (fig. 2). Banana Craze explores artistic responses to the political and cultural impact of banana plantations across the Americas, resulting in a multifaceted inquiry into extractive economies. The project is also, as I will discuss, a contribution to an ongoing discussion about extractive approaches to art itself and the possibilities of digital projects as alternative

spaces for critical archival practice.

Banana Craze is divided into three areas of action: an art database that can also be browsed as a digital exhibition, an interdisciplinary educational resource connecting the material to other databases, and an ongoing series of events taking place in person and online. The database focuses on critical artistic approaches to the broad ramifications of the banana trade between 1960 and the present, and it can be browsed alphabetically, chronologically, geographically, and thematically. The thematic function presents the database in a digital exhibition format, foregrounding Solano and Serrano’s curatorial framing. This curatorial framework is articulated through an introductory essay on Banana Craze, descriptions of individual artworks, and short introductions to the three thematic sections, entitled “Violences,” “Ecosystems,” and “Identities” (fig. 3). The “Violences” section brings together artworks that denounce the collusion of foreign multinationals and corrupt governments in the abusive treatment of plantation workers and the disruption of local politics. As is made clear throughout the exhibition, this history prominently features the rise of the United States as a dominant power in Latin America and the Caribbean. “Ecosystems” centers on the impact of monoculture and monopoly on the region’s environmental and social ecosystems, examining how land and life are treated as resources to be extracted for profit, especially in economies dependent on the banana industry. As Solano and Serrano note, the banana is the most consumed fruit in the world, and Latin America and the Caribbean account for 75 percent of global exports.2 Finally, the “Identities” section explores the prominence of the banana in contested expressions of national and cultural identity across Latin American and Latinx groups, as well as in the formation of ideas about race and gender.

This diverse body of work provides the basis for the continuous unfolding of online and offline educational and research activities, which demonstrate the collaborative potential of digital research projects. Banana Craze serves as a teaching resource through the open-access syllabus “Bananas. History, Politics, and Visual Culture.” The syllabus expands the database’s reach by situating it within a broader history that begins with the introduction of bananas to the Americas in the early sixteenth century and provides an interdisciplinary approach to the material. It was produced in collaboration with historian Kevin Coleman, principal investigator of the digital project Visualizing the Americas (launched in 2023), which examines photographic archives pertaining to the struggles of banana plantation workers.3 The syllabus not only draws from both digital databases, but it also connects to other research and activist projects that involve the construction of digital platforms, such as the investigation of land dispossession, paramilitary violence, and banana monoculture in Colombia’s Caribbean coast conducted by the multidisciplinary research group Forensic Architecture (fig. 4).4 Finally, the ongoing production of publications and in-person and digital events—such as films, screenings, lectures, workshops, and smaller physical exhibitions at a variety of institutions—continue to extend this collaborative ethos.

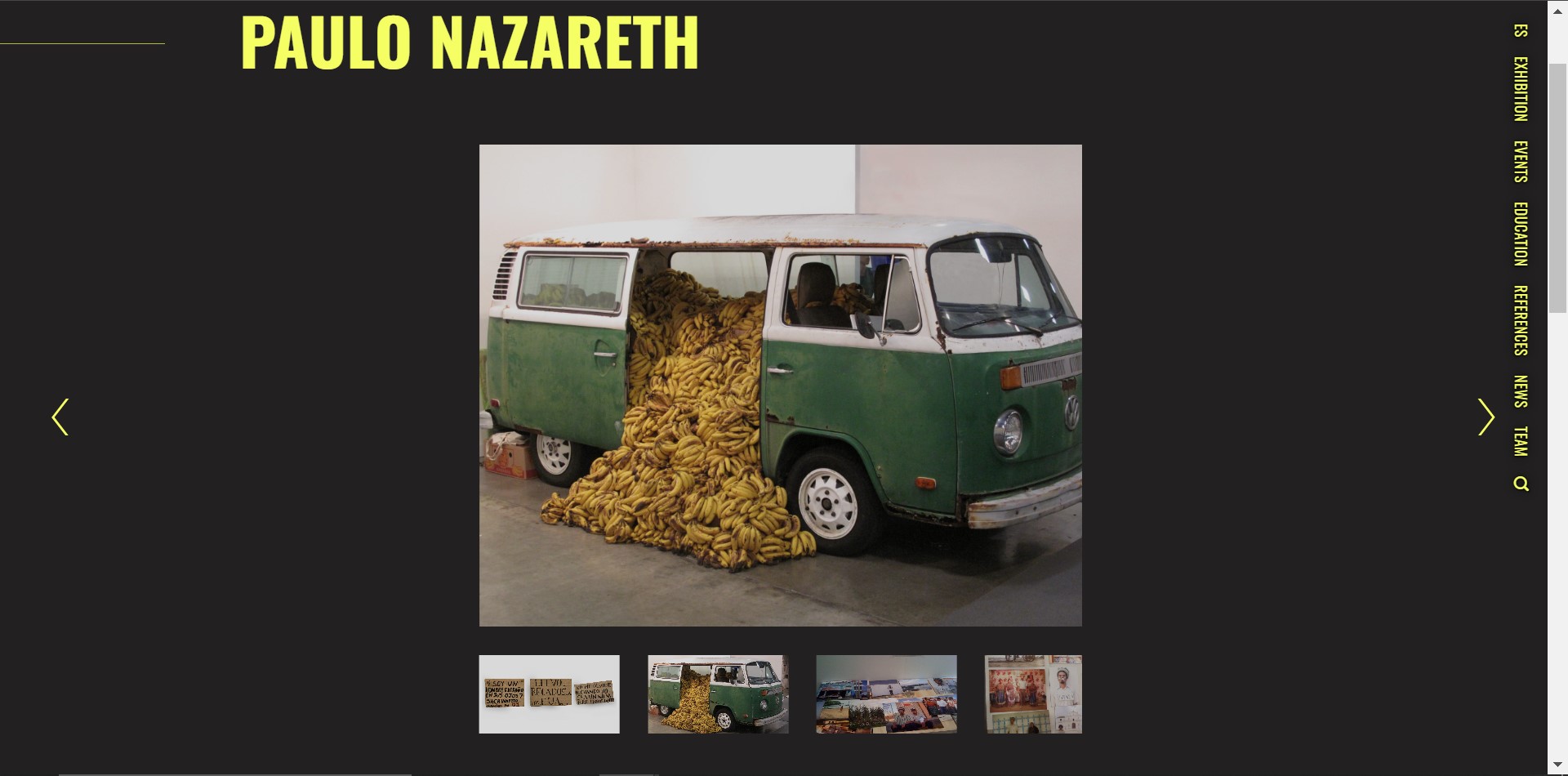

What is at stake in the project, then, is not only the analysis of the banana industry as a case study for the broad ramifications of extractivism or the production of an inventory of artists who provide points of entry into this complex subject; it is also an experiment in the form that such a research project can take. This is pertinent given that the extractive moves studied by the artists in Banana Craze find their corollary in the power imbalances structuring these artists’ relationships to international markets and institutions. While this theoretical framing of the project’s form is not explicitly foregrounded in its textual components, it is an undercurrent of the artistic production that Solano and Serrano have chosen to display. For example, as part of his project Notícias de América (News from the Americas), Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth walked on foot from Belo Horizonte, Brazil, to the 2011 Miami Art Fair, where he exhibited a Volkswagen bus filled with bananas from Guatemala in an installation entitled Banana Market / Art Market (fig. 5). Holding a poster with the inscription “My image of exotic man for sale,” the artist distributed the bananas to the cleaning staff for free while selling them in autographed form to fairgoers. In addition to highlighting the uneven mobility of people and commodities that characterizes the global economy, Nazareth also performed an elision between the banana as commodity and the artist’s work. As Solano and Serrano note in their description of Banana Market / Art Market, Nazareth staged himself as an “object of desire exposed to the exoticizing gaze of the collector,” highlighting “the commercialism of art” and “the imbalances of power that exist between producing and consuming countries.”5

This alignment of art and bananas is also reminiscent, of course, of León de la Barra’s art-historical chart. While playing on the peripheral positioning of Latin American artists in the most influential art-historical visualizations of modern art (such as Alfred Barr’s 1936 “Cubism and Abstract Art”), the chart also responds to the more recent asymmetries involved in the international art market’s appetite for Latin American art. In fact, it was part of a larger project to reimagine the form of art-historical research and curatorial work in view of the art world’s structures of production and consumption. Printed next to the banana bunch, a manifesto for a “Novo Museo Tropical” (New Tropical Museum) asks readers to consider the differential access to resources in art institutions outside of hegemonic art centers and the ever-present pressure on artists in these same regions to produce for the international market.

The chart generated a number of exhibitions, including Novo Museo Tropical, which León de la Barra curated at TEOR/ética in Costa Rica (July 21–September 16, 2012). The exhibition featured artworks and archival materials addressing the political, economic, and cultural repercussions of banana plantations. As such, Solano and Serrano credit it as an important resource for their own research of this subject.6 Yet beyond its focus on bananas, León de la Barra’s project is also a helpful interlocutor in analyzing the significance of new platforms for art-historical research, such as Banana Craze. León de la Barra presented Novo Museo Tropical as “a first approach toward building a new art history” and “an attempt to create an expanded field for tropical manifestations, which de-localizes it from any geography.”7 His contemporaneous “Manual for Exhibition Making in the Tropics” (2011–14) instructs his readers:

Do exhibitions everywhere, in white cubes, in black cubes, in wooden cubes, and in green cubes, in the jungle and floating in the river, in abandoned spaces and in spaces to be built, in the internet. . . . Think of the exhibition as a process, not as a final, perfect, static result. . . . Allow errors, surprises and collaborations to happen within the exhibition.8

León de la Barra was not alone in making this call to reshape art-historical research as an experimental and collaborative process in response to the realities of working in Latin America. In addition to important historical precedents going back to the 1960s, a number of collaborative efforts were emerging at this time with the aim of reinventing archival and curatorial practice in the Latin American context.9

A prominent example is the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Southern Conceptualisms Network), which was founded in 2007 by a group of Latin American researchers invested in reactivating the memory of artistic resistance in Latin America since the 1960s.10 This vast network (comprising about sixty researchers) has produced important collaborative projects that have queried the problems and possibilities involved in the mediation of the archives of Latin American art. As one of the network’s members, Miguel López, remarks, “New market demands for international art circulation, which exist in unequal economic and geopolitical conditions, mark the contradictions that we face today as mediators of cultural production between the South and the North.” Consequently, López writes, the network’s goal has been to create “new conditions for the discussion and preservation of these materials and documents in our own contexts.”11 The network has chosen to remain independent in order to institute new approaches to the geopolitics of archive preservation and presentation in collaboration with arts institutions across the North and South. One of these projects is the digital platform Archivos en Uso (Archives in Use), which organizes and makes available archival materials related to art and resistance in Latin America since the 1960s, in partnership with arts and research institutions in Argentina, Spain, and the United States (fig. 6).12

As these precedents make clear, Banana Craze is part of a field of discourse and practice that has not only reimagined the stories that can be told about artistic production in the Americas but also invented new forms for the presentation of these narratives in an effort to redistribute control over collective memory.13 Hosted by the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia, Banana Craze has been able to explore new networks of solidarity extending beyond the sphere of academic and arts institutions—the texts on its digital platform, for instance, were translated into English by the UK-based nonprofit organization Banana Link, which campaigns for fair and equitable production and trade in bananas based on environmental, social, and economic sustainability.14 The broad relevance of Solano and Serrano’s line of research for current political and environmental struggles creates the possibility for new forms of collaboration. As Banana Craze continues to grow, it will be instructive to see how this experiment reflects on its own structure and form, specifically regarding its potential as a model for sustaining and disseminating art-historical research on matters of political urgency.

Cite this article: Sonia de Laforcade, “Art, Bananas, Cash: Learning from Banana Craze,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18978.

Notes

- The poster was first printed as part of the project O Cartaz Como Espaco Expositivo Expandido, curated by Kiki Mazzucchelli and designed by Mel Duarte. León de la Barra describes it as a response to previous art-historical charts, including Miguel Covarrubias’s “Tree of Modern Art” (1933), Alfred Barr’s “Cubism and Abstract Art” (1936), and Ad Reinhardt’s “How to Look at Modern Art in America” (1946). It is available for download on León de la Barra’s blog, January 25, 2011, https://centrefortheaestheticrevolution.blogspot.com/2011/01/diagrama-tropical-um-poster-bananeiro.html. ↵

- Juanita Solano and Blanca Serrano, “Banana Craze,” Banana Craze, accessed February 18, 2024, https://bananacraze.uniandes.edu.co/language/en/exhibition. ↵

- Visualizing the Americas is a collaborative effort between the principal investigator, Kevin Coleman, and the University of Toronto Mississauga Library. See “About Us: Public History and Decolonizing the Archive,” Visualizing the Americas, accessed February 18, 2024, https://visualizingtheamericas.utm.utoronto.ca/about. ↵

- “Dispossession and the Memory of the Earth: Land Dispossession in Nueva Colonia,” October 12, 2021, Forensic Architecture, https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/land-dispossession-in-nueva-colonia. ↵

- “Paulo Nazareth,” Banana Craze, accessed February 18, 2024, https://bananacraze.uniandes.edu.co/obras/arte,identidades/paulo-nazareth. ↵

- Juanita Solano and Blanca Serrano, “Banana Craze,” Banana Craze, accessed February 18, 2024, https://bananacraze.uniandes.edu.co/language/en/exhibition. ↵

- “Novo Museo Tropical,” TEOR/ética, accessed February 18, 2024, https://teoretica.org/2012/12/31/novo-museo-tropical/?lang=en. ↵

- León de la Barra’s “Manual for Exhibition Making in the Tropics” was first published in C-32 Sucursal: La Ene en Malba, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Malba, 2014). An earlier version appeared in COOOOOOP FANZINE, edited Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Philippe Parreno and Jean-Max Colard, published by Kunsthalle Zurich in 2011.The text is now available at León de la Barra, “Manual for Exhibition Making in the Tropics,” May 28, 2020, Centre for the Aesthetic Revolution (blog), https://centrefortheaestheticrevolution.blogspot.com/2020/05/manual-for-exhibition-making-in-tropics.html. ↵

- Some important precedents in the Brazilian context where León de la Barra has been especially active are the work of curators Frederico Morais and Walter Zanini in the 1960s and 1970s. See Sonia de Laforcade, “Click, Pulse: Frederico Morais and the Comparative Slide Lecture,” Grey Room 73 (Fall 2018): 96–115; Cristina Freire, “A Network of Museums: The Impeccable Dialectic of Walter Zanini,” Art Journal 73, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 20–45. ↵

- Their website is https://redcsur.net. ↵

- Miguel A López, “Micropolitics of the Archive,” Field Notes 2 (December 2012), https://aaa.org.hk/en/like-a-fever/like-a-fever/micropolitics-of-the-archive-part-i-southern-conceptualisms-network-and-the-political-possibilities-of-microhistories. ↵

- Their website is https://archivosenuso.org. ↵

- Other early examples of multilingual digital archival projects developed in this vein include the Documents of Latin American and Latino Art project, initiated in 2002 by the International Center for the Arts of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which focused on developing access rather than acquisition and involved the collaboration of partner institutions across Latin America and the United Staes. See “What is the ICAA Documents Project?,” ICAA, accessed February 18, 2024, https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/page/documents-project. Another notable example is the Hemispheric Institute Digital Video Library, launched in 2005 with a focus on performance practices in the Americas. See “HIDVL Overview,” Hemispheric Institute, accessed February 18, 2024, https://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/hidvl.html. ↵

- “Our Team,” Banana Craze, accessed February 28, 2024, https://bananacraze.uniandes.edu.co/language/en/#team. ↵

About the Author(s): Sonia de Laforcade is Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at Radboud University.