Artistic Journeys: Assignments Engaging Primary Source Materials

Imagine taking one of my courses, either American Art of the Fin de Siècle or American Modernism: Alfred Stieglitz’s America. You have been assigned to enter the mindset of an artist of Gilded Age America or the modernist circle surrounding Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and to have that individual travel to the major cultural event of the age, whether or not there is actual evidence that he or she did so: to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition or the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art (the Armory Show). Your task is to understand how the artist you choose as your virtual guide through the course would have responded to these groundbreaking events.

As your Gilded Age artist—Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942), for example—encounters the White City, you seek to capture her voice in a series of imagined letters, diary entries, articles for contemporary art journals or newspapers, painted or drawn sketches, notes on period postcards, or a combination of all of the above. A similar approach might be employed as you write about your American modernist, whether Marguerite Zorach (1887–1968) or one of the spectacle co-organizers, Arthur B. Davies (1862–1928), as they react to both the avant-garde and not-so-daring art on display at the 1913 Armory Show. Central to your artist’s Armory Show response will be his or her engagement with the diverse critical commentary circling the exhibition, as well as the individual works of art deemed intriguing enough to be reproduced on a postcard or caricatured in a cartoon, such as Marcel Duchamp’s notorious Nude Descending the Staircase, No. 2 (1912; Philadelphia Museum of Art) or William Glackens’s semi-placid Family Group (1910/11; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC).

Engagement with the art and artists of these cultural events does not end with this assignment, however; there is a more comprehensive overarching principle of the artistic journey. You will also design a virtual exhibition, with images and primary source material synthesizing the output of all the artists presented in the course with the point of view and contribution of your individual research artist.

The Visual Essay Exhibition Project (VEEP) aims to involve you from the first day in the art, ideas, writings, influences, and mindset of the primary course material and of your individually chosen research artist. You will create a virtual exhibition to be displayed in approximately fifty to sixty-five PowerPoint pages (or a similar software program) of juxtaposed images and quotations from the period, including those by your artist. Included in these pages are images of the period building that houses the exhibition along with gallery floor plans, with exhibition themes noted. You will write a ten- to fifteen-page guide to the exhibition highlighting the ideas conveyed by juxtaposition of quotations and images, including five works from the Georgia Museum of Art. The Virtual Exhibition will of necessity incorporate material explored in the previous assignment of the research artist traveling to the defining cultural event of the course. By the end of the class, the first assignment has dovetailed into the last (see appendices A & B).

If this seems daunting, you simply mirror many a student of my thirty-one years of assigning this two-part project. Yet after the VEEP has been turned in, students invariably concede that they learned more from this assignment than from a traditional research paper or final exam; many even confess their enjoyment of the process. Frequently, the VEEP reappears in applications for museum internships and even graduate programs. Immersion in course material, readings, and individual artists combined with creative juxtapositions of primary sources and images—both works of art and cultural artifacts—produces exciting, imaginative exhibitions that are not constrained by the logistics of actual exhibition curation: budgets, borrowing approvals, size constraints, or even buildings for the exhibition venue that may no longer exist. Students learn about the art and its cultural, political, and social contexts in a profound way and become intellectually invested in an individual artist of their choosing.

In many ways, these artistic journeys reflect, and even reenact, the lecture-discussion sessions of the course. Each of these two courses is organized thematically. The World’s Columbian Exposition serves as the foundation for American Art of the Fin de Siècle, which begins with an overview of the fair and then turns to various themes relevant to the art on display. These broad themes—such as “Memory and Nostalgia,” “Cosmopolitan Beauty,” “Orientalism,” “Sacred Goddess and the New Woman,” “The Heroic Present, Being Big and the Crisis of Masculinity,” “The American West Conquered,” and “Mind Cure: Spirit Seekers”—stimulate the choice of exhibition sections in each student’s VEEP.

The Armory Show is likewise presented early in my American Modernism course. This course, also arranged thematically, proceeds from “Alfred Stieglitz and Turn of the Century Art Nouveau Aesthetics” to “Modernist Institutional Invasions: the Photo-Secession, 291, and the Armory Show,” “New York City as Modernist Vision,” “Transcendental Equivalence, Theosophical Visions, Emersonian Enlargement and the Élan Vitale,” “Going Primitive and Amerika,” “New York Goes Dada,” and “The Machine Age and the World of Tomorrow.” Ideally, each student’s research artist would fit into each of these sections, but this is not always the case. For the VEEP in either course, therefore, students must first incorporate the artists presented in the lectures, and then find appropriate opportunities for comparison with their research artist, although there may be themes in which their artist is entirely absent.

Primary sources appear in virtually every class lecture, and my PowerPoints provide a model for the students’ VEEP while also presenting material for their artists to respond to as they take their own artistic journeys. Primary sources can comprise many things, including works of fine art, magazine advertisements, popular illustrations and cartoons, posters, postcards, piano music sheet covers, and other ephemera, as well as commercial photographs such as stereographs, cartes de visite, and guidebook images. Period quotations drawn from primary sources such as letters, magazine articles, guidebooks, novels, poetry, and aesthetic, political, social, or religious writings also accompany the images. In addition to engaging students in close interpretive analyses of the visual material, class time involves interpreting how the quotations illuminate artistic motivations or expand our understanding of paired works of art. This juxtaposition of text and image primes the students for their VEEP, which must include an amalgamation of primary sources with images on every page.

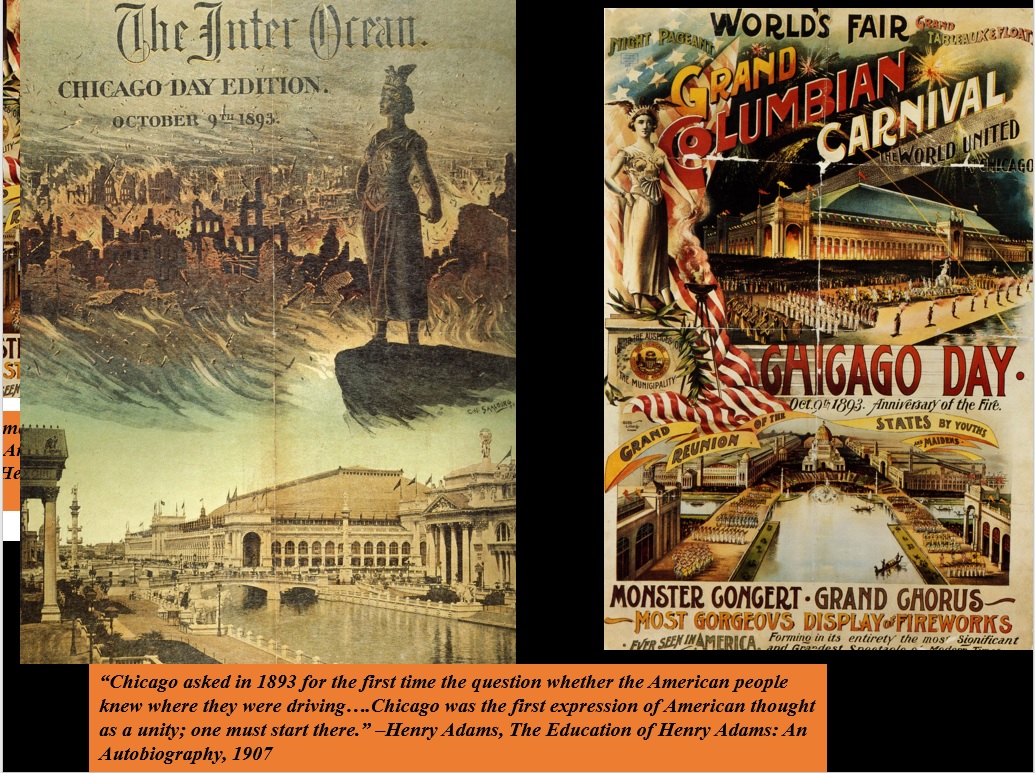

For example, in the first section of the American Art of the Fin de Siècle course, the supplement cover of The Inter Ocean: Chicago Edition, dating from October 9, 1893, is placed on the viewer’s left of the PowerPoint slide, with its personification of Columbia overlooking the charred ruins of the Chicago Fire of 1871 revitalized into the White City (fig. 1). Filling the right side, a color broadside of Columbia watching a nighttime parade in front of the Manufacturer’s Building advertises the Grand Columbian Carnival for Chicago Day, October 9, in which “the world united in Chicago,” and a banner announcing “a grand reunion of the states by youths and maidens” floats above the Court of Honor. The broadside promises a “monster concert,” “grand chorus,” and the “most gorgeous display of fireworks ever seen in America forming in its entirety the most significant and Grandest Spectacle of Modern Times.” Such bravado was not unusual in the tourist placards for the fair. It also echoes other statements of the time that elevated the World’s Columbian Exposition as third in national importance after the American Revolution and the Civil War. Juxtaposed with these two images of Chicago Day is a quotation by Henry Adams from his 1907 autobiography, which reiterates the conception of national rebirth after the division of war: “Chicago asked in 1893 for the first time the question whether the American people knew where they were driving. . . . Chicago was the first expression of American thought as a unity; one must start there.” 1 This statement resonates with the idea conveyed in the images of Chicago transmuting from ashes into the White City, as well as the promotional language used to drive visitors to the city and the fair.

In response to this presentation, students might reuse Adams’s quotation in their VEEP and juxtapose it with completely different images: an Impressionist interpretation of the Court of Honor, perhaps, or photographs of Louis Sullivan’s soaring Chicago skyscrapers, or something farther afield that requires inspiration as well as independent research to make an unexpected connection. As students assume their artist’s voice, they may choose to respond to Adams’s consideration of the fair as a monumental realization of Americanness in a diary excerpt or even a newspaper editorial. By using this quote in the first-person travel narrative and the VEEP, the essential ideas of the World’s Columbian Exposition and its importance to Gilded Age America is creatively assimilated into the student’s consciousness. And they learn about Henry Adams.

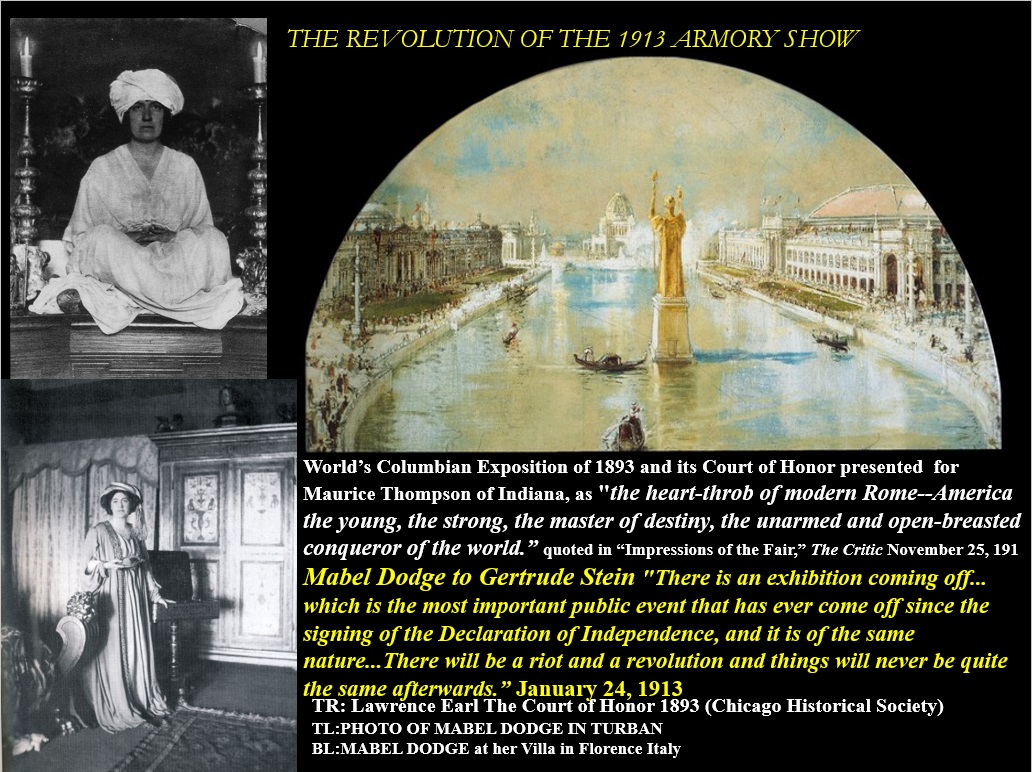

The Armory Show appears early in the American modernism course also, in the second section, within the context of the formation of the Photo-Secession movement by Stieglitz and Edward Steichen (1879–1973), which features the artistic transformations of modernism in photography as related to the other arts. To set the stage for the Armory Show, my opening slide juxtaposes two images of Mabel Dodge, one as Buddhist afficionado and the other as fashionable Florentine socialite, with Lawrence Earl’s watercolor of the World’s Columbian Exposition’s Court of Honor (fig. 2). Underneath Earl’s painting, a quotation by Maurice Thompson of Indiana praises the White City as an embodiment of “the heart-throb of modern Rome—America the young, the strong, the master of destiny, the unarmed and open-breasted conqueror of the world.”2 Below Thompson’s quote, Mabel Dodge’s famous letter to Gertrude Stein exuding the revolutionary significance of the upcoming Armory Show offers a counterview: “There is an exhibition coming off . . . which is the most important public event that has ever come off since the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and it is of the same nature. . . . There will be a riot and a revolution and things will never be quite the same afterwards.”3 The contrast between the exhibitions indicated by these divergent statements is further demonstrated in a series of PowerPoint slide comparisons of works of art displayed at the World’s Columbian Exposition and at the Armory Show, highlighted by quotations of critical responses. For example, John Singer Sargent’s painting Miss Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth (1889; Tate Britain) riled viewers at the world’s fair with its seemingly barbaric patterns, femme-fatale hair that never seemed to end, and the subject’s audacious, invented gesture of crowning herself, but it did not provoke the accusations of artistic arson, rape, and murder that Henri Matisse’s “toad-like” Blue Nude did (1907; Baltimore Museum of Art). Sargent irked some at the exposition, but Matisse became the most hated artist of the Armory Show.In addition to these focused examples, by including the newspaper pages of art criticism, illustrations, and cartoons about the fair or exhibition in my lecture PowerPoints, students are encouraged to analyze them and then asked to imagine their individually assigned artists responding to them as they attend the events.

In my American Art of the Fin de Siècle class, undergraduate Charlotte Gaillet mined not only the several art-historical monographs on her chosen artist, Cecilia Beaux, but she also found a more intimate view and a clearer sense of her artist’s voice in the Archives of American Art, where she happily hit the jackpot of full digitization. Reading letters, diaries, academic papers, poems, and printed documents pertaining to Beaux’s life sparked Charlotte’s imagination as she began to craft Beaux’s imagined diary entries and letters responding to the World’s Columbian Exposition’s Court of Honor, Wooded Isle, Midway Plaisance, and Woman’s Building, as well as the various works of art and cultural entertainments on display. Few of the primary sources related to Beaux in the archives, however, are credited to the years surrounding the world’s fair. Instead of employing the archives to cite specific accounts from Beaux’s writings about the exposition, the archives served as a starting point to gauge the tone and style of Beaux’s writing that then translated into the crafted entries of Charlotte’s project. Specific documents that contributed to the imagined responses of Beaux to the fair included Beaux’s diaries from 1875 to 1877 and 1905, which provided a model for how Beaux maintained a descriptive diary of her everyday life. Letters to Beaux’s sister Aimee Ernesta “Etta” Drinker (1852–1939), describing her time in Paris in 1888 and 1889, offered a means of emulating her correspondence of the time period so that Beaux could explain her reactions to the various exposition displays in fictive letters to family members and friends.

Two documents in the archives that directly relate to Beaux’s experience of 1893 added authenticity to Charlotte’s narrative of Beaux’s artistic journey to the fair. J. C. Nicoll’s letter of April 6, 1893, from the National Academy of Design, notifying Beaux that she had been awarded the Dodge Prize at the annual exhibition, along with remuneration of three hundred dollars, testifies to Beaux’s national artistic standing as she makes her way to the exposition to see her own oil paintings on display in the Palace of Fine Arts and the Woman’s Building. Even more exciting, the actual non-transferable admission ticket to the Palace of Fine Arts that Beaux possessed, dated October 14, 1893, with her name written on it, and torn in half, proves that Beaux physically attended the fair.4

In Charlotte’s paper, Beaux relates her artistic journey to the many acres of the exposition through several diary entries beginning on October 9, 1893, and ending at the art exhibitions on October 14. Beaux often rated her days in her diary entries, so Charlotte ends Beaux’s first day with the assertion, “Today was a good day.”5 Interspersed letters to family add a more intimate dialogue to the adventure. Arriving by train, Beaux muses in her fictive diary not only about her anticipation of the wonders of the fair, but also on where she would like to take her career after her return from Paris in 1889:

A warm, bright day. I traveled by train to arrive in Chicago to experience the most talked about event of the year, the World’s Columbian Exposition at Jackson Park. Many of my friends who have sent postcards from the fair explain it as a feat of the century, and as a culmination of America’s past with a nod to the future progression of the country. After studying in Paris from 1888–89, I have been struggling with my return to America. I want to stray away from portraiture; however, the choice to be a portrait painter was a practical decision of familial obligation. My family was once concerned when I moved from porcelain painting to canvas painting, so I am sure this move away from portraiture will cause much unrest in the Leavitt household. I must be sensible in my career, allowing for a steady earning to compensate for the misfortunes of my father and mother’s side of the family.6

Charlotte, drawing upon her research on Beaux, uses her artist’s journey to convey her artistic struggles and feelings about female independence, along with specifics about the fair. One especially clever example, echoing an illustration I showed in class, involves Beaux recounting being “transfixed” by two women taking pictures with Brownie cameras that they had purchased from the Eastman Kodak stand in the Manufacturer’s and Liberal Arts Building. Charlotte uses Beaux’s voice to ruminate on how the photographic act freed women, as the advertising at the time asserted:

I felt as though taking pictures of the fair was a way for these women to immortalize the independence they experienced while strolling through the World’s Columbian Exposition. Not only were the photographs providing memorabilia of the sites the women saw, but [they] also provided a visual representation of the progression women have made in society.7

Beaux’s concern about how women negotiated the growing dangers of urban society is further related as she recalls the rumors about young women visiting the fair and then mysteriously disappearing. She notes that without a chaperone, she needs to be extra careful “against the criminal elements of society.” Here, Charlotte ably inserts the realities of the American serial killer, H. H. Holmes, who terrorized the World’s Columbian Exposition, as told in the course’s required text, Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City.8

Most of all, Charlotte’s extensive consultation of primary source guidebooks, such as Martin’s World’s Fair Album-Atlas and Family Souvenir and Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed, direct Beaux to plan out her visit, just as the millions of visitors to the fair did, recounting the facts and responding to the judgments about the exposition displays asserted in their pages. Writing to her friend May Whitlock, Beaux compares Chicago’s fair to the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, which they both visited, noting the competing marvels of Eiffel’s Tower and Ferris’s Wheel and concluding that the latter embodied the continuity of life with a welcome assertion of technological progress.9 In Charlotte’s excellent paper, Beaux’s artistic journey to the World’s Columbian Exposition reveals a broad knowledge about the fair and a deep understanding of the issues at stake for the independent female artist seeking to make her aesthetic mark on American soil.

The Armory Show inspired artistic journeys that likewise confronted a changing world, though one seemingly more chaotic and jarring than the World’s Columbian Exposition. Using the various online links to primary sources for the Armory Show, especially those housed by the Archives of American Art, with its many catalogues, brochures, postcards, letters, and artifacts, along with individual artist sources, graduate student Erin Riggins created a series of fictive diaries by Marguerite Zorach about her participation in this monumental cultural event. Marguerite, along with her husband, William Zorach (1887–1966), found their oil paintings, Study (no. 782), Portrait (no. 783), and An Arrangement (no. 784) accepted by the Armory Show Domestic Committee, and upon settling in New York after their marriage on December 24, 1912, were able to attend the exhibition. Erin set up her diaries by positing “the recovery of Study from a New York flea market,” noting how this long-lost painting, which was actually exhibited at the Armory Show, “provides a significant piece of the puzzle regarding American women artists’ representation at the ground-breaking exhibition. . . . Zorach’s writings provide valuable insight from a necessary, and, thus far, absent, perspective—that is, the woman artist’s perspective—into what has been considered one of America’s ‘great awakenings.’”10 Erin then provided a table of contents for Zorach’s “recovered diaries” with appropriate dates: “The Acceptance Letter”; “The Opening”; “Visiting 291,” “The Americans”; and “The French (Henri Matisse).” For example, the entry for January 31, 1913, remarks on the artist’s hopes for a better reception from the public and critics than she received in California, and it notes, “I’ve seen what seems like hundreds of advertisements in the papers in the single month I’ve been in New York.”11 Erin’s Zorach diaries present a lively and personal response to individual works exhibited at the armory as well as to the press and critical coverage of the exhibition. She used Zorach’s invented diaries to express the inevitable frustrations American artists felt at viewing the art of their European contemporaries and reading the critical response to art on both sides of the Atlantic:

March 17, 1913. William brought home this month’s issue of Arts & Decoration this afternoon.1 I did not expect to be mentioned—William and I haven’t had a chance to establish ourselves in New York yet—but nonetheless, I flipped through frantically searching for coverage of American artists with a small, secret hope that the name ‘Zorach’ would catch my eye. . . . What I found regarding the American showing at the armory at times made my blood boil, while at other moments I found myself nodding my head in absolute agreement. We American artists are embarking upon a renaissance, but it can only be one that is entirely ours. Of course, we seem tame next to the French. When you set one nation’s art as the standard, anything else is doomed to pale in comparison. By pointing us to Europe’s avant-garde in an attempt to show us what they expect of their pre-meditated artistic revolution, the critics have stopped us dead in our tracks. There can be no planning ahead or imitating of another nation in the creation of an American modern art. If one seeks an exclusively American art, one must put on an exclusively American show. We will innovate rot and decay if we have to; the point is that it will be our rot and decay.

1 The March 1913 issue (Vol. 3, No. 5) of Arts & Decoration was devoted entirely to coverage of the Armory Show.

Erin’s notes trace how she crafted this entry from primary sources of critical response and Zorach’s own writings.

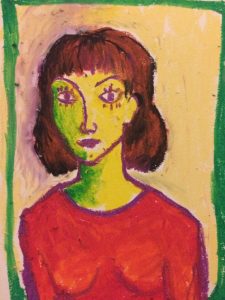

Finally, because Erin wanted to recreate Zorach’s lost painting based on its only description in an unfavorable review by the New York American, Erin created her own reproduction of Study. As Erin notes in her citations, Zorach received an unfavorable New York American review by Aloysius P. Levy, in which he wrote of the sickly nature of her portrait’s subject: “In the ‘study’ by Marguerite Zorach, you see at once that the lady is feeling very, very bad. She is portraying her emotions after a day’s shopping. The pale yellow eyes and purple lips of her subject indicate that the digestive organs are not functioning properly. I would advise salicylate of quinine in small doses.”12 Illustrated here is Erin’s attempt to recreate this lost work by Marguerite Zorach (fig. 3).

As these few examples attest, students are truly inspired by assignments engaging primary sources and the opportunities that resources such as the Archives of American Art and myriad online collections afford them to enter into the mindsets of artists and to relive history. They come to a deeper understanding of key cultural events and an individual artist’s experience, and they have a lot of fun on this journey—and to be honest, so do I.

Appendices

Appendix A: Charlotte Gaillet, “Nostalgic Progression: Coping with the Fin de Siècle in America,” Visual Essay Exhibition Project for American Art of the Fin de Siècle, Fall 2018, https://1drv.ms/p/s!AtVc8OWUs1CCbA3ibHjCDE9xZws

Appendix B: Erin Riggins, “Stateside Modern: Marguerite Zorach and the American Modernists,” Visual Essay Exhibition Project for American Modernism: Alfred Stieglitz’s America, Fall 2017, https://1drv.ms/p/s!AtVc8OWUs1CCcRy7n2R1ZvnJAss

Cite this article: Cite this article: Janice Simon, “Artistic Journeys: Assignments Engaging Primary Source Materials,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2302.

Notes

- Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams: An Autobiography (1907; reprint, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1918), 343. ↵

- Maurice Thompson of Crawfordsville, Indiana, cited in “Impressions of the World’s Fair,” The Critic, 20, no. 614 (November 25, 1893): 334. ↵

- Mabel Dodge to Gertrude Stein, January 24, 1893, quoted in Martin Green, New York 1913 (New York: Collier Books, 1988), 95. ↵

- J. C. Nicoll to Cecilia Beaux, New York, April 6, 1893, Cecilia Beaux Correspondence 1890–95, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. See the ticket to World’s Columbian Exposition, Palace of Fine Arts, with handwritten name, Cecilia Beaux, October 14, 1893, Box 3, Folder 13. ↵

- Charlotte Gaillet, “Cecilia Beaux Travels to the World’s Columbian Exposition,” October 8, 2018, paper submitted for ARHI 4420 American Art of the Fin de Siècle, University of Georgia, 6. ↵

- Gaillet, “Cecilia Beaux Travels to the World’s Columbian Exposition,” 3. ↵

- Gaillet, “Cecilia Beaux Travels to the World’s Columbian Exposition,” 10. ↵

- Erik Larson, The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America (New York: Vintage Books, 2003). ↵

- Gaillet, “Cecilia Beaux Travels to the World’s Columbian Exposition,” 16. ↵

- Erin Riggins, “An American Woman at the Armory: The Untold Story of Marguerite Zorach (1887–1968),” October 30, 2017, paper submitted for ARHI 6440 American Modernism: Alfred Stieglitz’s America, University of Georgia, 2. ↵

- Riggins, “An American Woman at the Armory,” 3. ↵

- Quoted in Riggins, “An American Woman at the Armory,” 10n27. ↵

About the Author(s): Janice Simon is the Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Associate Professor of Art History at the Lamar Dodd School of Art, University of Georgia