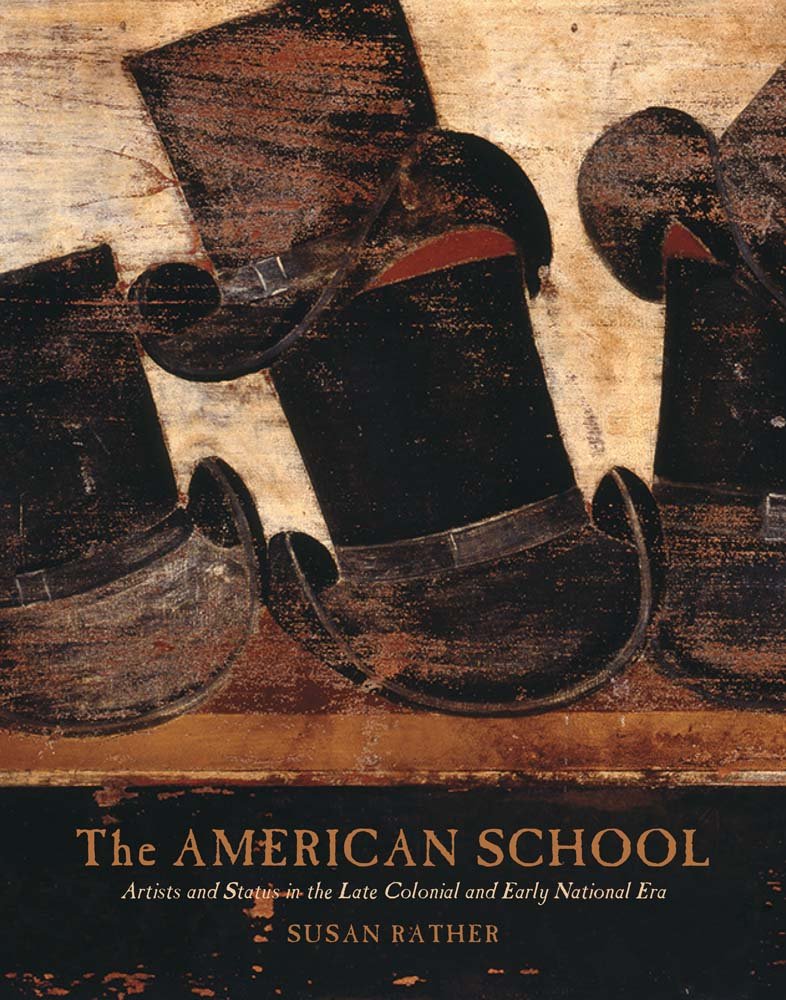

The American School: Artists and Status in the Late Colonial and Early National Era

Susan Rather

New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art, 2016; 316 pp.; 100 color illus.; 80 b/w illus.; ISBN: 978-0-300-21461; Hardcover: $75.00

In her richly documented and illustrated monograph, Susan Rather surveys the lives and careers of several key figures in the history of American art to examine the changing social status of artists in the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century transatlantic world. This book complements an active area of art-historical research, which has seen a significant number of important publications in recent years.1

Rather addresses the status of the artist as attached to the physical demands of the painted medium in order to assess how the combination of social forces and individual artistic efforts at self-definition led to a broad evolution in identity, from the eighteenth-century artist-craftsman, to the gentleman-intellectual of the Revolutionary era, and finally to the modern artist-genius of the early republic. The first part of the book offers three comparative perspectives on the 1760s through close examination of the careers of two canonical artists, John Singleton Copley in Boston and Benjamin West in London, together with a lesser-known figure in American art history: William Williams, a painter active in Philadelphia and New York.

In the first chapter, Rather discusses Copley’s reaction to the social tensions that surrounded the position of artists and artisans working in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic. Starting with Copley’s well-known self-portrait in pastel in contrast to his portrait of Paul Revere, the author convincingly unifies the Boston and London periods in the life of the artist by demonstrating the strength of the painter’s artisanal values throughout his career.

The second chapter examines a fascinating artist who has remained largely outside the mainstream history of American art. William Williams was born in Wales in the second quarter of the century. After moving to the American colonies by way of seafaring, he emerged in Philadelphia as a limner and music teacher in the 1750s. Rather argues that Williams’s presence leads us to question our preconception of what it meant to be an artist in colonial America, as he often branched out of the realm of portraiture to create conversation pieces, landscapes, maritime scenes, history paintings, and paintings for theater productions in Philadelphia and the Caribbean. Whether Williams was an anomaly in the eighteenth-century American art world remains open to question. However, Rather’s study shows that he shared similar concerns with West—whom he allegedly taught in Philadelphia—and Copley. Williams, just like his famous colleagues, manifested the desire to articulate his practice in a larger narrative of art making between craft and the liberal arts.

The third chapter focuses on West’s early career in Italy and London, and on his strategy to build a name for himself in the metropolis of the British Empire. West arrived in London at a time of intense discussion about the status of painting as a liberal art. He was an active participant in the debates that led to the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768, and he would later become its second president. In the 1760s, West capitalized on the spirit of experimentation in the realm of history painting and positioned himself at the forefront of artistic innovation in London by painting a number of North American subjects. At the same time, the painter opened his studio to numerous students, becoming a mentor to a generation of both American and British artists.

The second part of the book considers the role that portrait painting played in the newly founded United States by looking at the representation of painters in New York print culture and at the success of Gilbert Stuart as a portraitist after his return to America at the turn of the nineteenth century. Instead of focusing on the lack of support reported by artists invested in history painting, Rather considers the young republic as a fertile ground for portraiture and for artists ready to embrace this genre. She asserts that artists became important actors in the new republic because the act of portrayal took on particular urgency in the political battles between Federalists and Democrat-Republicans over the future make-up of the new nation. From this perspective, Stuart’s return to America was timely. As an artist who openly professed to dislike anything other than portraiture, he was soon seen as the founding figure of an American school of portraiture.

The central question in Rather’s account is what it meant to be an American artist in the colonial era through the early republic. She specifically calls attention to Stuart’s British citizenship as he worked in America, and she ends the book with an appraisal of the role played by West’s autobiographical works in setting up William Dunlap’s 1834 The Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States. This significant treatise positioned West as a founding figure in the historiography of American art, even though the painter left Pennsylvania at the end of the 1750s, fully adopted Britain as his home, and never returned to his native land.2 Rather’s important questioning of American identity in The American School is both a strength and a limitation. On the one hand, her interrogation identifies the roots of a discourse that have proved tremendously influential on the historiography of American art and situates them within a particular historical moment: when claims over national identity were tied to the social status of artists and the battle over painting as liberal art or craft. This argument, rooted in 1760s London and the Academic training model, was revived in early nineteenth-century America, when the trope of the self-taught artist asserting national authority over European training emerged.

On the other hand, Rather’s monograph remains bound to the dominant narrative it sets out to revise. It participates in a longstanding tendency to anoint northeastern works of art as representative of American colonial painting, understood to be a provincial branch of British culture slowly separating itself out into a national school in the aftermaths of the American Revolution. Indeed, the author dedicates four chapters out of six to Copley, West, and Stuart, and gives priority to three urban centers of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions—Boston, New York, and Philadelphia—while highlighting their relationship with London over any other cultural center of the Atlantic world. On this point, the focus of the book prevents a truly critical examination of the norms that have come to be accepted as the national paradigm. Rather does acknowledge in the introduction that scholarship on the history of the Atlantic world has recently turned attention to the significance of exchanges beyond the Anglo-American Atlantic, and that art historians have started to embrace the exciting opportunities that the South and the Caribbean present to American art history.3 While historians of the Atlantic world have placed connections between late eighteenth-century revolutionary events in the Americas and France and political proceedings that rocked the foundation of Atlantic empires at the forefront, scholars in material culture have called attention to the circulation of objects and ideas across the French, Spanish, Dutch, and British Empires. Archaeologists and historians of architecture, too, have paid greater attention to the South and the Caribbean regions in recent years.4

Rather’s chapter on William Williams emerges as one of the most significant contributions of her book. With connections to Benjamin West, Dutch culture, literary pursuits, and theater productions in Philadelphia and the Caribbean, the life and work of the Welsh-born artist offer tantalizing possibilities for expanding the history and understanding of American eighteenth-century art. Rather’s study of Williams’s career establishes, beyond doubt, the significance of Dutch regional culture for the works he painted in New York at the eve of the Revolution. However, important aspects of his career remain elusive, including his early training after he left Bristol (England), as well as his sojourns in the Caribbean basin. In addition, while very few known works can be attributed safely to Williams, a few manuscript sources combined with Rather’s close study of about a dozen extant paintings supports Williams’s own estimate that his output reached more than 180 canvases. As a recently discovered painting—attributed to a follower of Francis Hayman, but showing many of Williams’s characteristics—suggests, looking for further evidence of the latter’s career is a challenging but not impossible task. The discrepancy between currently known material evidence of Williams’s art and the written record is an apt reminder of both the need for further research and the difficulties one might encounter with the identification of paintings and archives related to artists who, for numerous reasons, are not at the core of the historiography of American art.

The American School is an important and timely intervention into the history of eighteenth-century American art. Attending to the historical construction of the historiography of the field, this extensive study of a significant, although previously underestimated, artist included within the book opens new avenues of inquiry and invites us to reflect on the narratives we write and the relative importance of the material evidence we employ to produce them. Finally, although this is a relatively expensive book, it should be commended for its handsome design, as well as the size and quality of its illustrations.

Cite this article: Marie-Stéphanie Delamiare, review of The American School: Artists and Status in the Late Colonial and Early National Era, by Susan Rather, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1620.

PDF: Delamaire, The American School

- Key related texts include the award-winning book by Margaretta Lovell, Art in a Season of Revolution: Painters, Artisans, and Patrons in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); Marcia Pointon, Portrayal and the Search for Identity (London: Reaktion, 2013); and most recently, Zara Anishanslin, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016). ↵

- William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Designs of the United States (New York: George F. Scott, 1834). ↵

- Maurie D. McInnis, “Little of Artistic Merit? The Problem and Promise of Southern Art History,” American Art 19, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 11–18. ↵

- William Klooster, Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History (New York: New York University Press, 2009); Deborah Krohn and Peter N. Miller, Dutch New York Between East and West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); Dennis Carr, et. al., Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 2015), among others. ↵

About the Author(s): Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire is Associate Curator of Fine Arts at Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library.