Beatrice Glow and the Botanical Intimacies of Empire

A digital print on silk by Beatrice Glow depicts a tobacco plant surrounded by archival images of the slave ship hold and coffle. Tobacco (fig. 1) refuses conventional expectations for a work of “Asian American” art. Instead of centering histories of Asian migration, it centers the materiality of the tobacco flower, surrounded by symmetrical tendrils of leaves and smoke interspersed with images of enslaved Africans. From a distance, the images of Atlantic slavery resolve into the botanical images: the coffle is aligned with the framing pattern of leaves; the diagrams of the hold could be large leaves emerging from beneath the flower. Tobacco—which appears here as both plant and intoxicating clouds of smoke—is also paired with the silk fabric on which it is printed, bringing together two highly mobile “global luxury products.”1 When Glow included this work in a 2017 solo exhibition at the James B. Duke House (the former home of the American Tobacco Company founder, now home to the New York University Institute of Fine Arts), she critically juxtaposed the opulent institutional setting, evident in the gilded molding and crystal chandeliers, with the material and corporeal sources of that opulence.2

Placing documents of the slave trade alongside the material sensuality of silk and the intoxicating effects of tobacco smoke—products originating in China and the Americas—Glow’s work refuses to reproduce narratives of Asian American cultural nationalism that critics and activists have shown to be complicit with the anti-Black, settler-colonial state; instead, it suggests that the histories of dispossession, enslavement, and exploitation that gave rise to tobacco and silk as global luxury products provide some shared (if also deeply uneven) common ground between Indigenous, Black, and Asian histories under racial capitalism.3 As Susette Min observes in Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art, there is:

an expectation for cultural works labeled “Asian American” to represent Asian American history and experiences that have been occluded due to injunctions, laws, and misrepresentations, all of which have disenfranchised Asian Americans from determining and shaping their own destiny, identity, and culture.4

Like the works that Min discusses, Tobacco exemplifies a subjectless Asian American practice that “shift[s] the categorical aims of Asian American art away from a politics of recognition to a reformation of perception, reorienting the futurity of Asian American art.”5 By decentering the immigrant subject, Glow is able to trace a range of material exchanges that extend from the molecular scale of biochemical responses to the transnational scales of bioprospecting and commodity exchange.

Tobacco highlights one of Glow’s central themes: the ways in which global histories of empire and conquest—especially those that extend into and across the Pacific Ocean—have been entangled with plants. Alongside the human migrations that have long been the focus of Asian American scholarship and culture, plants have played a profound role in reshaping ecological and social relations on both sides of the Pacific, and throughout Oceania. Scholars of the “botany of empire” have shown how imperial and colonial projects were fueled by bioprospectors seeking botanical specimens and Indigenous botanical knowledge that might be exploited for profit, often through medical, culinary, or cosmetic commodities that materially interact with users’ bodies; meanwhile, scholars of “ecological colonialism” have traced how colonial terraforming—through invasive species, mass extinctions, plantations, and other modes of intensive agriculture—profoundly transformed Indigenous ecological relationships.6 Along with tobacco, Glow’s work has investigated the colonial histories and sensuous human experiences produced from botanical materials, such as nutmeg, black pepper, cacao, cinnamon, opium, and tea.

This essay focuses on how one of Glow’s major installations, Aromérica Parfumeur (2016), engages the embodied senses (in particular, smell) to critically stage the botanical intimacies of empire. Taking the form of a perfume gallery in a Santiago, Chile, shopping mall, Aromérica Parfumeur draws on the colonial histories of plants to both expose and decolonize the historically sedimented networks of racial and colonial violence that underlie bourgeois olfactory practices. In tracing the colonial geographies of plants (and of the sensory experiences enabled by plants), Glow’s artworks collapse the vast scales of settler colonial occupation and imperial conquest into the intimate scales of embodied experience and the molecular exchange of breath or scent. By centering intimate scenes of encounter with botanical products historically entangled with colonial, imperial, and racial dispossessions, her work offers an approach to understanding the “intimacies of empire” at the levels of interspecies entanglement and chemosensory perception.7

Through immersive works such as Tobacco and Aromérica Parfumeur, Glow addresses the sensuous and multispecies dimensions of imperial intimacies—the material interactions with the more-than-human world that have both shaped and been shaped by human migrations and relationships. Scholar Lisa Lowe documents how Asian immigration—along with many other processes of “racial governmentality”8—came into being amid the transnational, cross-racial migrations and intimacies produced as a result of capitalism’s constitutive dependence on the extraction of value through racialized dispossession and exploitation, even as national and colonial archives obscured those unruly connections. Similarly, Glow excavates “the often obscured connections between the emergence of European liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.”9

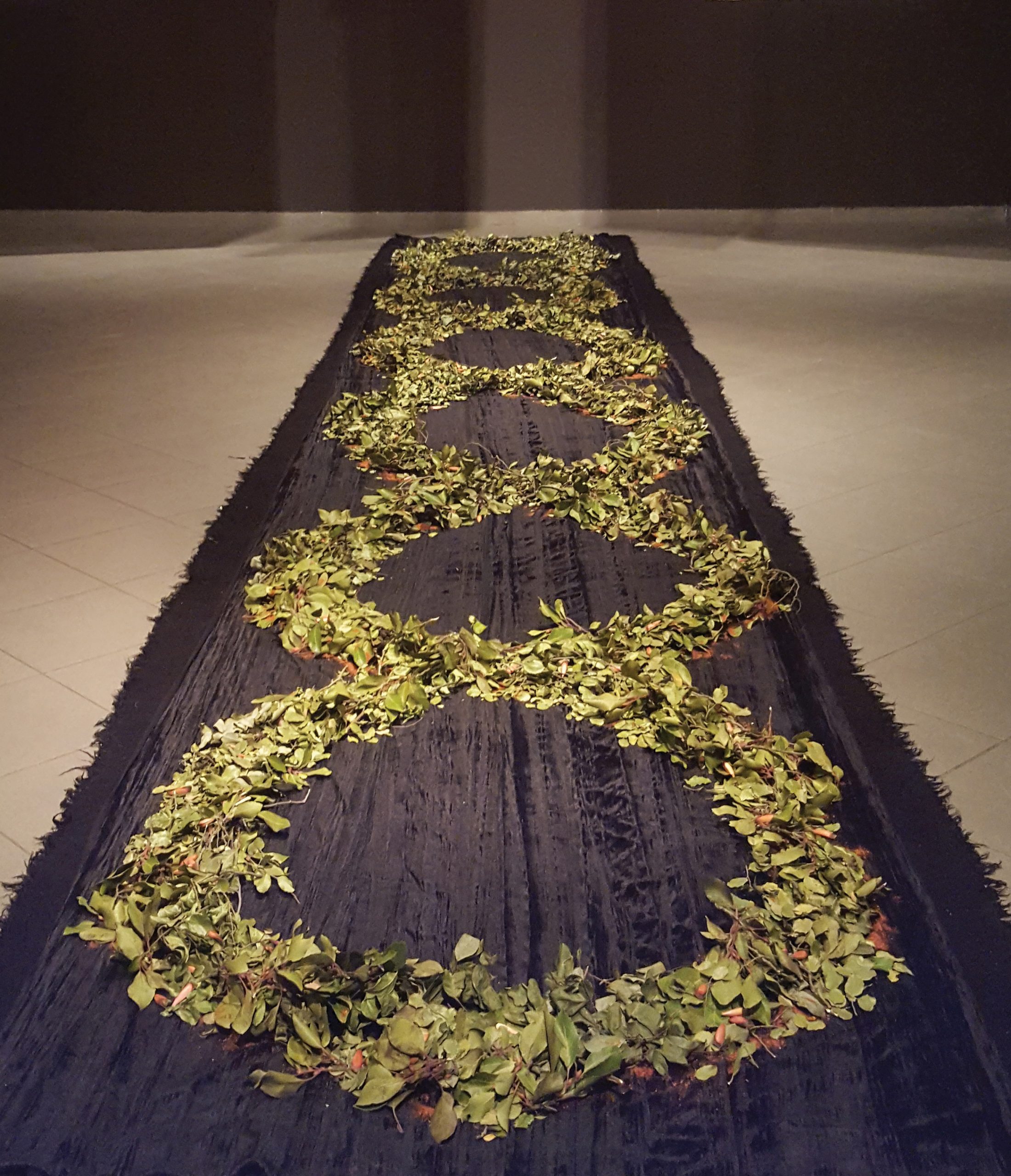

Sited at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile’s gallery in the Mall Plaza Vespucio, the installation Aromérica Parfumeur immediately confronted visitors with the violent histories of settler colonialism and imperialism that underlie the institutions of the shopping mall and the art museum. The installation motto—“Ad Loca Aromatum, Desde 1492” (Navigate to Places Where Spices Are, Since 1492)—underscored the desire for access to aromatic spices that motivated Christopher Columbus’s voyages, as well as the transoceanic ecological transformations known as the Columbian Exchange and the genocide that these voyages set in motion (fig. 2). Inside the gallery, visitors encountered an array of multisensory works, including a reproduction of Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map titled Ad Loca Aromatum, empty perfume bottles, embroidered silk shawls featuring illustrations of spices (including Tobacco), an altar of leaves arranged in the shape of a double helix, and a series of bottled scents accompanied by graphic posters (fig. 3). The retitled image of Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia contrasts the apparent visual distance of the rationalized cartographic grid with the rapacious olfactory desires of colonial “spice hunters.”

Glow’s perfumes, displayed in matching sets of bottles and bell jars atop lightboxes, appealed to visitors’ olfactory curiosity: lifting a bell jar enabled visitors to smell a sample of each perfume. At the same time, the perfumes and accompanying posters drew attention to the colonial regimes of extraction that enable the production of commodified fragrances and culinary spices. For bourgeois consumers who have historically been concentrated in the west (and whose numbers have been growing in Global South nations such as Chile), perfume functions as a mark of distinction within the context of bodies and spaces that are otherwise painstakingly deodorized.10 In addition to atmospherically delineating distinctions such as class, race, and gender, it catalyzes social and sexual intimacies. Glow’s focus on spices also highlights olfaction’s vital role in gustatory taste (through retronasal receptors as well as olfactory receptors on the tongue), and therefore to the more-than-human intimacies of eating as a process that remakes both individual bodies and social relations. Smell—a sense frequently disparaged in the history of western aesthetics as excessively intimate, visceral, and immersive—is elevated by perfume and rationalized by chemical synthesis into a powerful tool for sustaining social hierarchies. The sense of smell has been a subject of extensive research by marketing experts interested in exploiting its powerful connections to memory, instinct, and identity. As a result, scented products now extend far beyond personal perfumes, permeating the spaces of everyday life. Despite this profound and understated influence, olfaction enjoys at best a marginal position among art historians, critics, and curators.11 Glow’s multisensory practice challenged visitors to interrogate the spatially vast and historically deep origins of everyday olfactory pleasures and intimacies—the violent histories that have rendered available the odorants and spices we regularly take into our bodies.

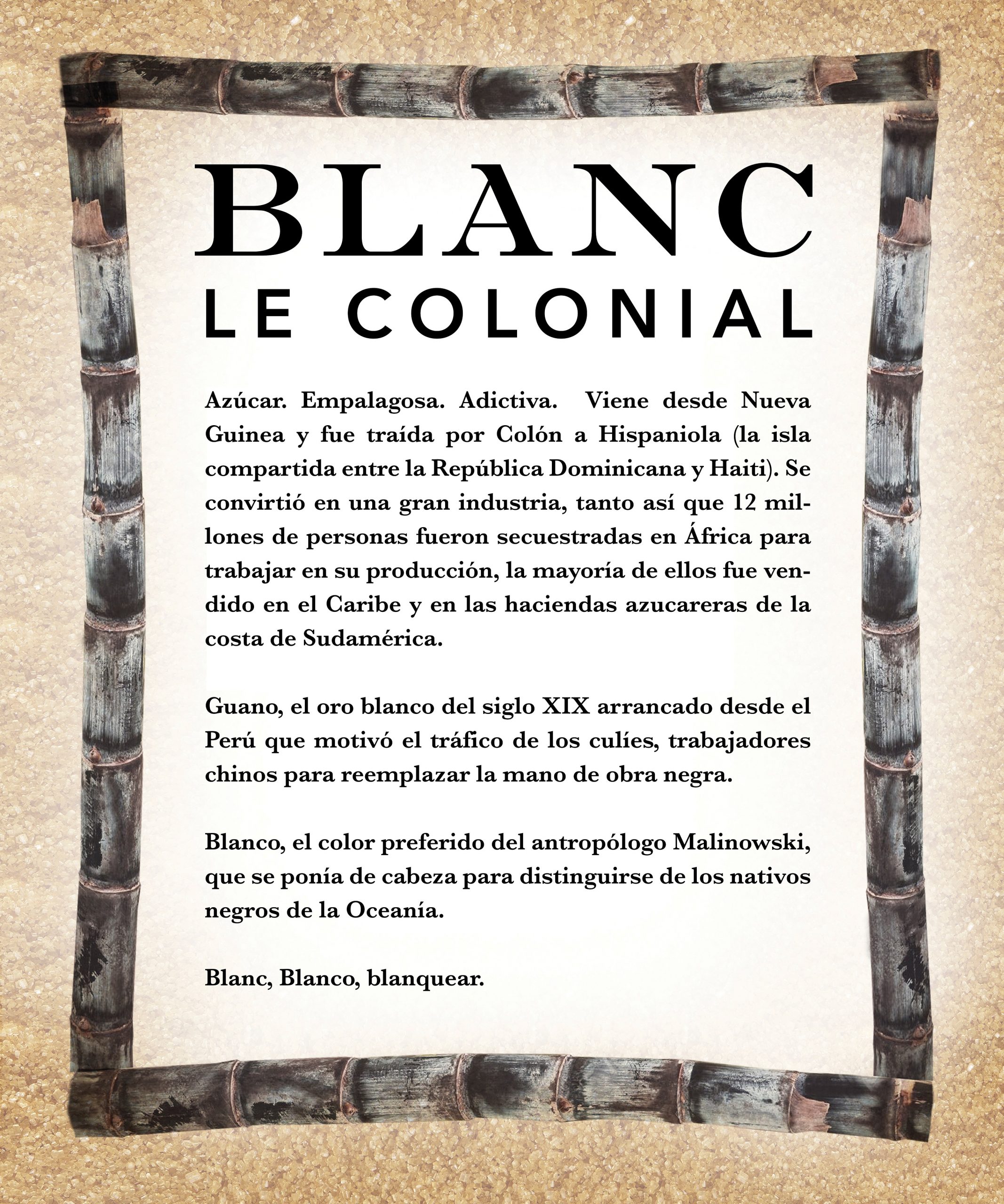

While sampling perfumes that featured scents such as cloves, nutmeg, peppercorns, tobacco, sugar, cinnamon, and cacao, visitors encountered posters detailing the conditions of colonial violence and racialized labor that have characterized the extraction and commodification of these plants. In contrast with the uniform bottles that commodify and contain perfumes by detaching them from contexts of extraction, Glow’s posters featured graphic representations of each scent’s botanical sources: cinnamon bark, nutmeg seeds, opium poppies, or sugarcane (fig. 4). They also provided critical historical context for the scents. For example, the poster accompanying El Picante (a fragrance featuring nutmegs and cloves) notes that “They only grew in the Maluku Islands until the Portuguese broke the monopoly of the Arabs and Chinese,”12 and recounts that nutmeg motivated the Netherlands to trade the island of Manhattan to England in exchange for the present-day Indonesian island of Rhun in a transaction premised upon the dispossession of the Lunaape/ Lunaapeew/Lenape and Bandanese people.13 Other posters note how black peppercorns motivated British imperial depredations in India; how sugar and guano—both referred to as “white gold”—were produced through racialized unfree labor in both Caribbean plantations and Peru’s guano islands (worked by Chinese coolies); how Tabaco—a plant with precolonial roots in the Americas—was grown by “millions of humans kidnapped from Africa” on occupied Indigenous lands in the Americas; how cinnamon motivated Pizarro’s expedition into the Amazon as well as the Portuguese “enslavement” of Ceylon; and how opium has functioned as both “the botanical arm of the English that produced the fall of the Chinese empire” and a contemporary export enriching drug traffickers enabled by the United States’ occupation of Afghanistan.14

While most of the scents were “pleasant,” Glow notes that “El Picante . . . and Oro Negro (black pepper) were not dialed down at all and people were often taken aback as those notes can be harsh”; similarly, while it did not contain the scent of guano, “Blanc: Le Colonial was nauseatingly sweet with sugary and milky synthetic fragrance mixed in with vanilla reinforced by tonka beans. It’s an overdose of sweetness” (fig. 5).15 The discomfort induced by these scents—along with the dissonances between the more pleasant scents and the informational posters—simultaneously exposed the power of olfactory experiences and recontextualized that experience. At the same time, the occasionally overpowering scents undermine both the posters’ visual fetishism of colonial exports and the abstract, uniform design of the perfume bottles: these olfactory compositions cannot be reduced to a single botanical source, and they refuse to be contained. This defamiliarization of bourgeois olfactory conventions provokes critical questions: can awareness of these violent histories decolonize visitors’ scent associations, recoding Glow’s perfumes not as “exotic” fragrances but as both products and agents of colonialism? Can the scent of nutmeg be reappropriated as an embodied experience that connects Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape and Bandanese histories of dispossession? Can tobacco smoke be experienced not as a recreational intoxicant but as a transformative scent that draws connections between the disparate, ongoing experiences of Indigenous genocide and Black fungibility? In both mapping and making visceral multiple routes of dispossession, Glow does not just provoke visitors to question the aesthetic pleasure derived from bourgeois perfumes—she also presents multiple yet interconnected experiences of botanically motivated exploitation as the grounds for allyship between historical and ongoing subjects of racial, imperial, and colonial violence.

In elaborating these connections between the heterogeneous modes of dispossession, plantation labor, and ecological colonialism imposed on Asian, Indigenous, and Black Atlantic populations, Glow draws on an archipelagic conception of heterogeneous and overlapping connections within and across oceanic space. In her online artist statement, Glow foregoes the pan-ethnic and national coordinates that are often demanded from Asian diasporic artists; instead of retracing her family’s immigration trajectory from Taiwan to California (where she was born), Glow articulates her ancestry in relation to multilayered colonialisms:

I am sensitive to questions of sovereignty, erasure, indigeneity, belonging, and migration due to the multiple colonialisms in my ancestral homeland, Taiwan. While I am not a culture bearer, I relate to Asian Indigenous cultural heritage as my mother’s village is an Amis cultural stronghold. Understanding myself as a visible racialized settler in the Americas, I work in allyship with indigenous communities to resist complicity in settler-colonialism. Inspired by the Austronesian seafaring heritage of voyaging from Taiwan and settling Oceania, “all islands are connected underwater” guides my relational worldview.16

Invoking the hypothesis that Oceanian civilizations were first settled by Austronesian seafarers from Taiwan, Glow connects her ancestral proximities to the Indigenous Amis people with a range of archipelagic geographies (many of them still subject to colonization and its aftermaths) throughout the Pacific world.

Glow’s self-positioning resonates with two recent lines of scholarly inquiry: the “archipelagic” turn in American studies and recent calls to attend to the frictions, ruptures, and possibilities for allyship that subtend categories such as the “transpacific” and “Asian Pacific Islander.” Building on the foundational archipelagic thought of epeli hau’ofa and Édouard Glissant,17 Brian Russell Roberts and Michelle Ann Stephens theorize the archipelagic network of transnational relationships that has been obscured by historiography’s continental bias:

The narrative of continental America (which has been a geographical story central to US historiography and self-conception) has . . . completely eclipsed the narrative of what we are terming ‘the archipelagic Americas,’ or the temporally shifting and spatially splayed set of islands, island chains, and island-ocean-continent relations which have exceeded US-Americanism and have been affiliated with and indeed constitutive of competing notions of the Americas since at least 1492.18

Following Roberts and Stephens, an archipelagic Asian American practice would look beyond the monolithic Asia-United States trajectory of cultural nationalism in order to discern heterogeneous, multidirectional modes of movement, proximity, allyship, and dissonance among Asian diaspora, Indigenous nations, and other inhabitants of America’s constantly exploited and frequently overlooked “planetary archipelago.”19 An archipelagic framework situates Asian American issues in geographic and ecological terms: not only through the histories of immigrant and refugee communities but also the circulation of more-than-human species, and the transformation of land and ecologies as capitalism has experimented with different modes of exploitation and dispossession throughout the Pacific world. In an illuminating overview of archipelagic imaginaries in Asian American art, Margo Machida writes, “Trans-oceanic imaginaries, combined with the idea of islands as multi-located historic and affective subjects, provide these artists with a dynamic pivot to engage shared Pacific and global intersections between Asian, Indigenous, and western peoples.”20

Such intersections between Asian diasporic and Indigenous histories occur on uneven terrain. As critics have noted, the frequent conflation of Asian Americans with Pacific Islanders—including in the 1990 and 2000 United States Census and in a 2004 proposal to rename the Association for Asian American Studies—has obscured vast historical and cultural differences between these groups.21 Asian American and Indigenous Pacific communities have lived through disparate yet interconnected histories of racialization, dispossession, migration, and resistance—histories that have positioned Asian diaspora as settlers on unceded Indigenous land in both Taiwan and US-occupied territories. Acknowledging her ties to settler colonialism in both these locations, Glow frames Asian diasporic identity in terms of her responsibility toward Indigenous communities displaced throughout the Pacific archipelago.

Glow staged these archipelagic connections at the opening of Aromérica Parfumeur by inviting Indigenous performers from both Rapa Nui and Southern Chile to “[transform] the National Museum of Fine Arts’ gallery into a ceremonial space.”22 To recognize ancestral ties across the Pacific, Glow recounts in the exhibition catalogue how she “invited David Akivi, a Rapa Nui culture bearer and founder of the cultural group Riu o te Rangi, to activate our seafaring memories and bring forth a Pacific narrative of maritime navigation that predates the Age of Exploration.” Akivi performed a song about “Hotu Matu’a, the Polynesian ruler that settled to Rapa Nui” after traveling there by canoe. Afterward, Glow and Akivi held the ends of a rope stretched to sixteen feet, “the length of an adult blue marlin,” and Glow shared a story about the blue marlin. A sacred fish in her grandmother’s village in Taiwan, the blue marlin represents the complexity of Pacific cultural and ecological intersections: “Generations of blue marlin have witnessed the intertwined ecological and historical fate of the Americas and Asia Pacific through eons as it patrols the oceans.” As Glow explains, the blue marlin is both a symbol and a witness of the Austronesian migration throughout the Pacific that spans more than five thousand years, and “powerfully evokes reimaginings of human interconnectivity and diasporic circulations by diluting divisive notions of cultural borders.” In an affirmation of allyship and kinship, Glow stated, “this rope between David and I represents our trans-Pacific family relations.”

In the exhibition itself, Glow’s allyship with Indigenous people extends beyond the project of exposing settler colonial violence. In consultation with the Mapuche elder Delfina Curihuinca Huenchún, Glow incorporated Indigenous botanical products into a piece entitled Altar (Radal, Quillay, Peumo y Boldo de Ñuke Mapu) (fig. 6). A thirty-three-foot long arrangement of leaves “arranged like a double helix DNA chain, or perhaps multiple ouroboros” on the floor of the exhibition space, Altar contrasts sharply with the perfume bottles displayed on illuminated pedestals. Glow recounts that when she was invited to exhibit in Chile, “I felt like an uninvited guest given I had not requested permission from, nor made initial contact with, the Native Mapuche peoples.” When she arranged to visit Huenchún, “Delfina [Huenchún] shared that human beings are part of Ñuke Mapu, Mother Earth, and earlier in the week, they had gone to visit native trees and shared my intent about inviting the plants to partake in the Aromérica Parfumeur project. After seeking permission from the land, Delfina procured three large sacks of quillay, radal and peumo leaves.”23 Glow used these materials—along with piñones, merkén (a Mapuche smoked chili powder), and boldo leaves from the Araucanía region sourced through her network of friends—to create Altar. Commonly called “soapbark” in English, quillay (quillaja saponaria) is used as a soap and shampoo by the Mapuche and is also found in scented perfumes and cosmetic products; both quillay and boldo have historically been used for medicinal purposes by the Mapuche.24 According to Glow, merkén imparts a “smoky, spicy scent,” while the scent of boldo (peumus boldus) “is somewhat like a cross between a conifer and a eucalyptus tree and is slightly bitter.”25 She recounts that “The overall aroma [of Altar] was herbaceous and woodsy like being in an evergreen forest with laurel-like notes and soft hints akin to eucalyptus.”26 Glow worked with these unprocessed, indigenous leaves and scents only after receiving them as a gift, with permission from both Huenchún and the land.

Physically and conceptually, Altar occupies a central place in Aromérica Parfumeur: it not only grounds the exhibition in the place (ancestral Mapuche lands), but also presents a decolonized aroma that has not been produced through centuries of colonial dispossession and racialized exploitation. Whereas commodified bourgeois scents typically mystify their sources (often listing fragrance as an ingredient in order to avoid disclosing specific materials), Glow is forthright about both the work’s contents and the processes through which she received them. If perfume is an olfactory commodity that marks class distinction against otherwise deodorized background spaces, Altar presents indigenous leaves whose scents have long been part of the local atmosphere and its inhabitants. The “multiple ouroboros”/double helix pattern of the quillay, radal, peumo, and boldo leaves invokes continuance, renewal, and infinitude, while also drawing attention to the “trans-corporeal”27 exchanges by which scents enter and shape our bodies. If perfume has been a powerful driver of olfactory colonization, Altar decolonizes smell by affirming the vital and continuing importance of indigenous plants and Indigenous olfactory practices. Inhaling these scents, visitors briefly become materially intimate with indigenous plants, sensory values, and environmental relationships. While such an encounter cannot substitute for Mapuche knowledge and traditions oriented by these plants, Altar nevertheless acknowledges the urgency of both territorial and sensory decolonization.

With its striking blend of sensory immediacy, geographical nuance, historical depth, and visual/olfactory friction, Aromérica Parfumeur exemplifies the richness of subjectless Asian American art. Suspending the politics of cultural nationalism, Glow ranges far beyond the United States (although never outside the scope of its geopolitical and ecological influence). Refusing to imagine either ethnic inheritance or national belonging in monolithic terms, her work traces a vast range of archipelagic and interspecies connections across uneven terrain. Bringing visitors into intimate encounters with both colonial and Indigenous materials, her olfactory practice stages the botanical intimacies of empire in visceral, embodied terms. Glow’s practice of multisensory mapping—which connects carefully composed inhalations with vast and overlapping colonial and imperial histories—has much to offer those interested in rethinking Asian American aesthetics beyond the frames of nationalism, the racialized body, or the human.

Cite this article: Hsuan L. Hsu, “Beatrice Glow and the Botanical Intimacies of Empire,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021),https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11509.

PDF: Hsu, Beatrice Glow and the Botanical Intimacies of Empire

Notes

My thanks to Marci Kwon, Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, and Susette Min for their thoughtful and generative comments on early drafts of this essay—and to Beatrice Glow for her generosity in sharing information about her work.

- Beatrice Glow, Paintings and Prints, accessed April 21, 2021, https://beatriceglow.org/painting-prints. ↵

- The exhibition Beatrice Glow: Spice Roots/Routes was presented at Duke House, New York University Institute of Fine Arts, New York, March 22–June 19, 2017, and was organized by Kristen Gaylord and Kathleen Robin Joyce; see the archive of the Duke House exhibition series on the institute’s website, https://ifa.nyu.edu/events/duke-house-exhibitions.htm. Also see “Beatrice Glow: Spice Roots/Routes @ Duke House, NYU Institute of Fine Arts,” beatriceglow.org, April 18, 2017, https://beatriceglow.org/news/2017/4/18/beatrice-glow-spice-rootsroutes. ↵

- See Dean Itsuji Saranillio, “Why Asian Settler Colonialism Matters: A Thought Piece on Critiques, Debates, and Indigenous Difference,” Settler Colonial Studies 3 (2013): 280–94. ↵

- Susette Min, Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 16–17. ↵

- Min, Unnamable, 18. Min’s argument builds on Kandice Chuh’s influential call for a subjectless Asian American practice. Chuh argues, “If we accept that Asian American studies is subjectless, then rather than looking to complete the category ‘Asian American,’ to actualize it by such methods as enumerating various components of differences (gender, class, sexuality, religion, and so on), we are positioned to critique the effects of the various configurations of power and knowledge through which the term comes to have meaning.” Kandice Chuh, Imagine Otherwise: On Asian Americanist Critique (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 10–11. ↵

- On the botany of empire, see Yota Batsaki, Sarah Burke Cahalan, and Anatole Tchikine, eds., The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017); Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004); Londa Schiebinger and Claudia Swan, eds., Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); and on ecological imperialism, see Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004). ↵

- Ann Laura Stoler, “Tense and Tender Ties: The Politics of Comparison in North American History and (Post)Colonial Studies,” in Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History, ed. Ann Laura Stoler (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 23. ↵

- Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 195. ↵

- Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents, 1. ↵

- For a historical account of the emergence of this bourgeois “schema of {olfactory} perception based on the preeminence of sweetness,” see Alain Corbin, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 140–41. ↵

- For recent studies of olfactory art, see Larry Shiner, Art Scents: Exploring the Aesthetics of Smell and the Olfactory Arts (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2020); and Hsuan L. Hsu, The Smell of Risk: Environmental Disparities and Olfactory Aesthetics (New York: New York University Press, 2020). ↵

- Beatrice Glow, “El Picante,” in Aromérica Parfumeur, ed. Jeong-A Kim (New York: Beatrice Glow, 2018), 49 (my translation from Spanish). ↵

- Glow’s ongoing Rhunhattan project, initiated in 2016, explores this history in greater depth through a series of workshops, interactive media, community engagement, and collaboration with Bandanese and Lenape culture bearers. Beatrice Glow, “Rhunhattan: A Tale of Two Islands,” accessed April 21, 2021, http://beatriceglow.org/rhunhattan. ↵

- Beatrice Glow, “Oro Negro,” “Blanc: Le Colonial,” “Taboo: Tabaco,” “Eau de Colón: Gourmand,” and “Amapola Noir,” in Aromérica Parfumeur, 51, 53, 55, 57, 59 (my translations from Spanish). ↵

- Beatrice Glow to the author, November 19, 2020. ↵

- Beatrice Glow, “Artist Statement,” (undated). accessed April 21, 2021, https://beatriceglow.org/statement. ↵

- See epeli hau’ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” in Asia/Pacific as Space of Cultural Production, ed. Rob Wilson and Arif Dirlik (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 113–31; and Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). ↵

- Brian Russell Roberts and Michelle Ann Stephens, “Introduction: Archipelagic American Studies: Decontinentalizing the Study of American Culture,” in Brian Russell Roberts and Michelle Ann Stephens, eds., Archipelagic American Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 1. ↵

- Roberts and Stephens, “Introduction,” in Archipelagic American Studies, 10. ↵

- Margo L. Machida, “Pacific Itineraries: Islands and Oceanic Imaginaries in Contemporary Asian American Art,” Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas 3, nos. 1/2 (2017): 9–10. ↵

- See Vicente Diaz, “To ‘P’ or Not to ‘P’: Marking the Territory between Pacific Islander and Asian American Studies,” Journal of Asian American Studies 7, no. 3 (October 2004): 183–208; and J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “Asian American Studies and the Pacific Question,” in Asian American Studies After Critical Mass, ed. Kent Ono (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005), 123–43. ↵

- Beatrice Glow, “Centering Indigeneity in Vespuciolandia,” in Aromérica Parfumeur, 32, 28, 29. ↵

- Glow, “Centering Indigeneity in Vespuciolandia,” 23–25. ↵

- John Parrotta and Ronald Trosper, Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge: Sustaining Communities, Ecosystems, and Biocultural Diversity (Dordrecht, NE: Springer, 2011), 95. ↵

- Glow to the author, November 19, 2020. ↵

- Glow to the author, November 19, 2020. ↵

- Stacy Alaimo, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 2. ↵

About the Author(s): Hsuan L. Hsu is Professor in the Department of English, University of California, Davis