Returning to Dialectics of Isolation : The Non-Aligned Movement, Imperial Feminism, and a Third Way

This essay revisits the understudied Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists in the United States (1980) co-curated by artists Ana Mendieta (1948–1985), Kazuko Miyamoto (b. 1942), and Zarina (1937–2020) at the first women’s cooperative gallery in the United States, Artists in Residence Inc. (A.I.R. Gallery).1 It addresses the foreclosure of the history of art and activism in Third World women’s movements and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in North American histories of feminist art, and it challenges the exhibition’s subsumption into liberal feminist discourses of diversity, identity, and inclusion. In addition, the essay reinscribes Miyamoto and Zarina back into the exhibition history as co-curators alongside Mendieta; both Asian American artists are still not credited equally for their work.

Dialectics of Isolation is still largely attributed to Mendieta, beginning with the oft-cited, laudatory review in The Village Voice by Carrie Rickey entitled “The Passion of Ana.”2 Although Rickey notes that the show was coordinated by three artists, her review—along with subsequent scholarship—credits the conceptualization of the show to Mendieta. The story goes like this: Ana conceived and proposed the exhibition to the gallery leadership; Zarina designed the catalogue; and Kazuko handled its installation.3 Rickey’s exotification of the “passionate” Mendieta is evident from the review title. The tokenization of Mendieta by A.I.R. members, along with the absorption of her Silueta series into a “larger movement of white US feminism,” is noted by Julia Bryan-Wilson.4 Bryan-Wilson observes how Gloria Orenstein’s essay in Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics conflated Mendieta’s work into “a homogenizing context in which all ‘Goddess spirits’ are more or less equivalent, collapsing the cultural specificities and historical differences that Mendieta was keen to emphasize.”5 Jane Blocker similarly argues that feminist writers of the 1970s enacted a “whitening” of Mendieta’s work by appropriating it into “white-goddess models,” which the artist, in her subsequent solo show at A.I.R. Gallery, Esculturas Rupestres—Rupestrian Sculptures, resisted by referencing Indigenous, Taíno, and Afro-Cuban Santería gods through the Spanish-language titles and gallery notes.6 In response to the foreclosure of Caribbean influences and her racialization in the United States, Mendieta began writing about her own work to resist its appropriation by second-wave feminists, including her piece on “La Venus Negra” in an issue of Heresies on feminism and ecology.7 This text became part of a body of work that José Esteban Muñoz called her artistic performance of “a modality of brownness.”8 It must also be noted that Ana was the most white adjacent of the three artists, and that the formative time she spent in Iowa as a child involved socialization and intimacy with whiteness early in her life, unlike Kazuko and Zarina.

I argue that the continuing attribution of the intellectual labor of the exhibition solely to Mendieta is an extension of these various strands of tokenization, imperialism, and white supremacy within North American histories of feminist art and activism.9 These liberal narratives valorize individuality over collectivity, smooth out difference, and hierarchize the work these artists shared between them—with writing considered the highest intellectual labor, graphic design next, and physical installation last. I insist, instead, that the exhibition was, in its conceptualization, development, and execution, a truly collaborative project for which Mendieta, Miyamoto, and Zarina must receive equal attribution, particularly given their investments in Third-Worldism and a feminist praxis of decolonization.10

Third World New York

The germinal Dialectics of Isolation exhibition (fig. 1) was borne out of the friendship of three migratory artists who met in New York City in the mid-1970s and became part of its burgeoning art and activist movements. The artists shared their frustrations with second-wave feminism’s dismissal of the “double” oppressions of race and sex that Third World women faced and which were implicitly entangled with class, and with a provincial New York art world in which an awareness of histories of imperialism and anti-colonial resistance—such as the Cuban revolution, the aftermath of the United States detonating nuclear weapons over two cities in Japan, and India gaining independence from British rule—were absent. Kazuko came of age in American-occupied, postwar Japan, and Zarina in postcolonial India, where independence occurred simultaneously with the traumatic partition of the Indian subcontinent. Both artists were recent immigrants to the United States. Ana was a minor refugee from Cuba who arrived to the United States at the age of twelve, part of the clandestine Operation Peter Pan/Operación Pedro Pan.11 Between them, the artists spoke four languages: Urdu, Japanese, Spanish, and English.

A.I.R. was founded by twenty artists as a women’s cooperative gallery in 1972. The gallery’s first location at 97 Wooster Street in SoHo was next door to Anthology Film Archives and the Fluxus Fluxhouse.12 Members paid dues, attended monthly meetings, worked at the gallery, and participated in workshops. In exchange, they were given slots for solo shows every two years and kept all the revenue from their sales. Howardena Pindell (b. 1943), the only nonwhite co-founder of the space, recounted that every time she mentioned race in the monthly meetings, she was accused of bringing up something “political” that purportedly had no place in feminist discourse. Although she tired of what she called “imperial feminism,” it was the fees that ultimately led to her departure three years later.13 Unlike the married, middle-class members who did not have to work full time or had dual-household incomes, Pindell supported herself through a full-time job at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) while working evenings in her studio, and eventually she found it difficult to afford the membership fees.14

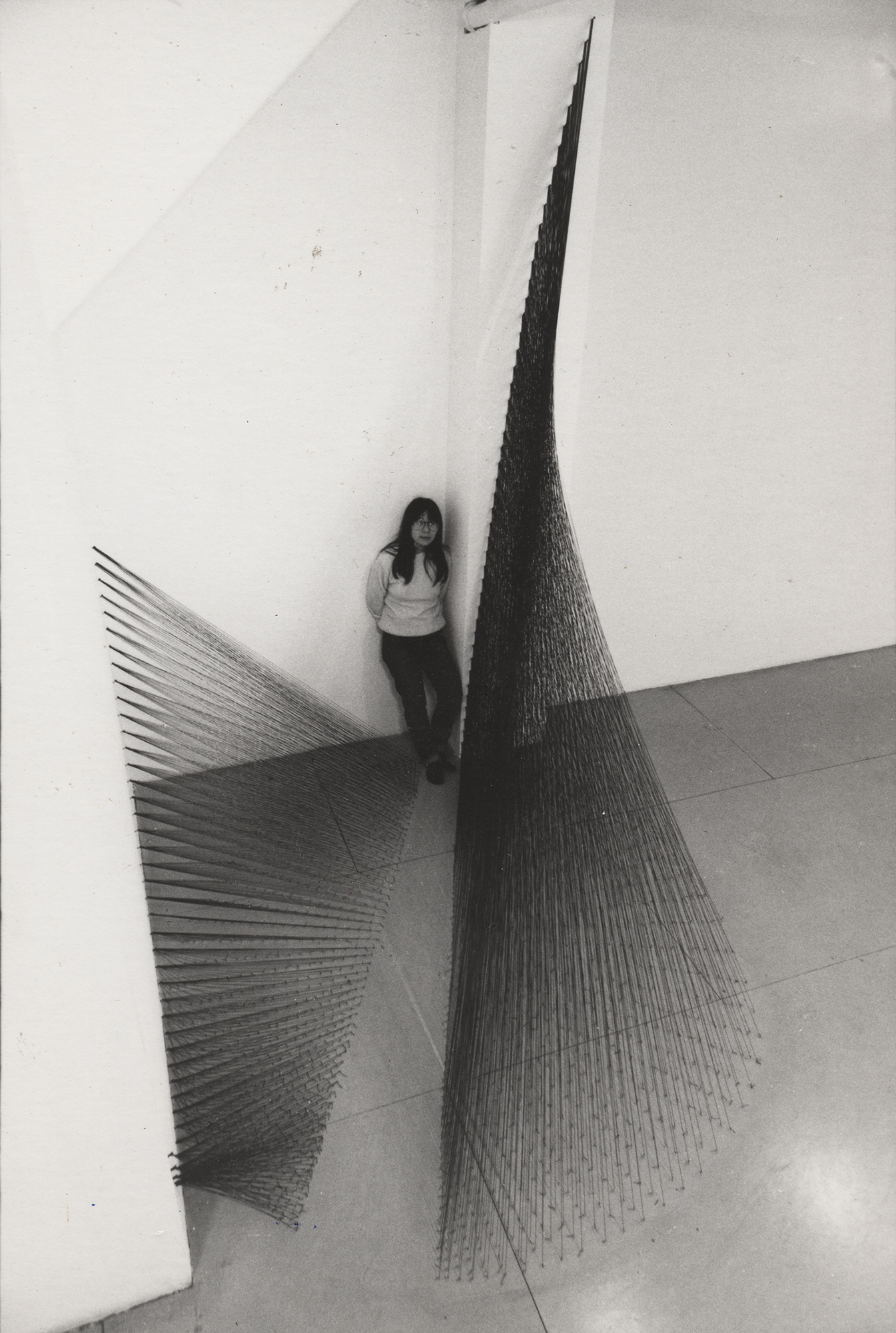

Miyamoto joined the gallery in 1974, two years after it was co-founded and ten years after moving from Tokyo, Japan, where she studied at the Gendai Bijutsu Kenkyujo, to New York in order to attend The Arts Student League.15 Miyamoto worked multiple jobs in the service industry before she was hired by Sol LeWitt as his first studio assistant. She made intricate, small-scale replicas of LeWitt’s open geometric structures and also assisted with his early wall drawing series. This work with LeWitt was formative for both artists; in Miyamoto’s practice, it marked a shift from expressionism toward Minimalism and Post-Minimalism.16 As Lawrence Alloway wrote: “Hers was not a simple action of imitation, however: on the contrary she pursued, with relentless subtlety, a three-dimensional potential implicit in the drawings but not realized by LeWitt.”17 At the time of the Dialectics of Isolation exhibition, Miyamoto was making her “string constructions” (fig. 2), in which she nailed linear arrangements of industrial cotton string between the wall and floor, creating a delicate matrix of overlapping threads. Her work dissolved the planar emphases of Minimalism, delicately inhabited volumetric space, deployed organic instead of industrial materials, and gave feminist form to the Latin etymology of the word “matrix,” as mater or womb. Miyamoto also introduced the feminine body back into her Post-Minimalist sculptures such as Yoshiko Chuma inside Trail Dinosaur (1978), a collaboration with the eponymous Japanese American dancer, choreographer, and performance artist (fig. 3).

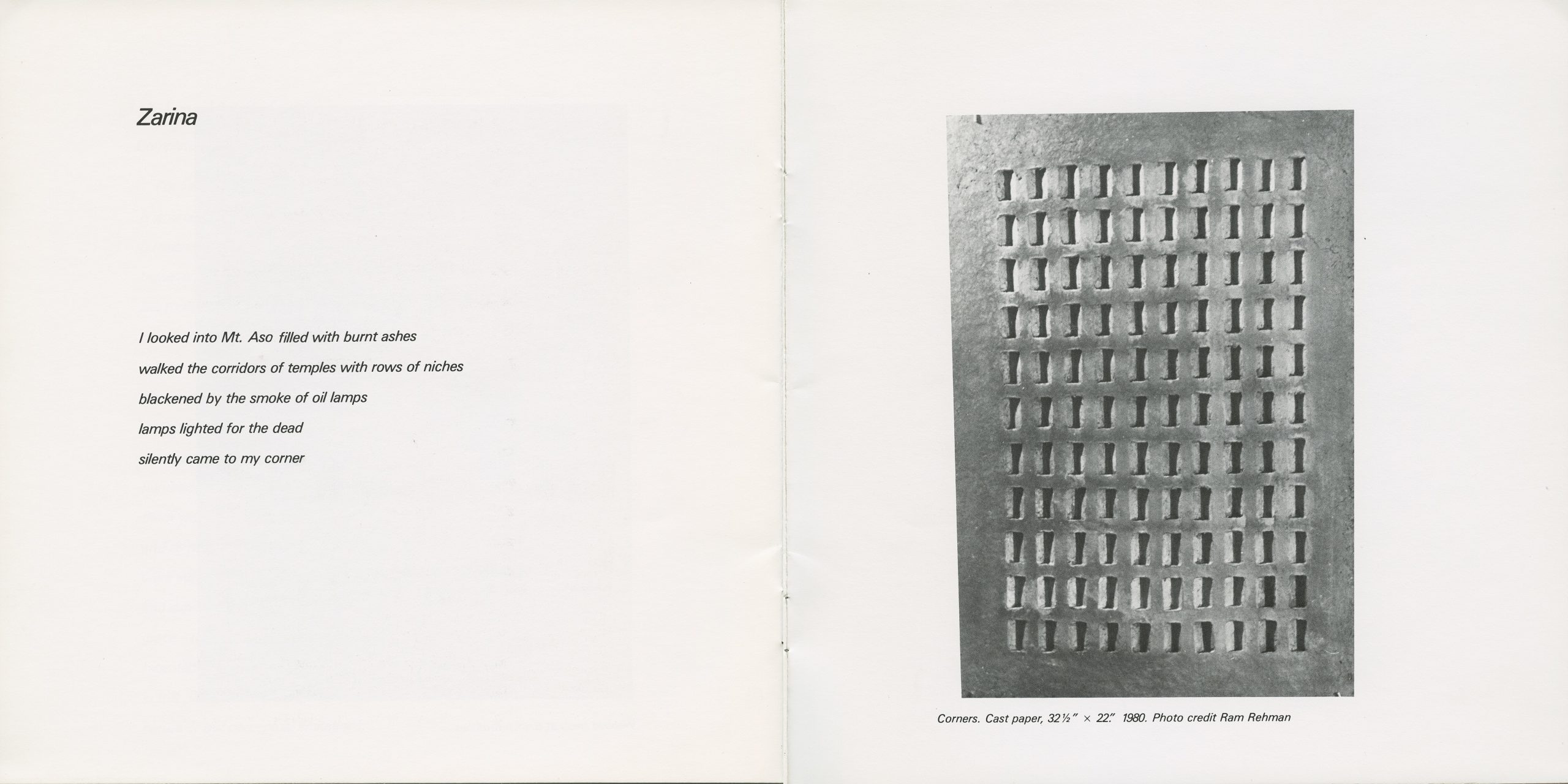

Zarina studied mathematics at Aligarh Muslim University in Aligarh, India, and began her peripatetic life after her marriage to a diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service.18 Though Zarina was already painting in India, it was only after the young couple moved to Bangkok that she began printmaking. In 1963 they moved to Paris, where she apprenticed at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17 before returning to New Delhi in 1968, where she made a considerable body of work on paper using salvaged wood.19 In 1974, she traveled to Tokyo on a fellowship to apprentice at Studio Yoshida, and the following year she moved to New York. At the time she co-curated Dialectics of Isolation, Zarina was recently widowed and facing financial hardship.20 She had just finished co-editing “Third World Women: The Politics of Being Other,” a special issue of Heresies and was teaching papermaking classes at the Feminist Art Institute (fig. 4) and doing freelance graphic design.21 She was also at work on a series of soft sculptures made of pulped paper that, like Miyamoto’s work, incorporated influences of Minimalism and Post-Minimalism. These include Corners (1980), which was displayed in Dialectics of Isolation, and a red-tinted, wafer-thin work with small perforations poetically entitled I Whispered to the Earth (fig. 5). Unlike Mendieta and Miyamoto, who were both members of A.I.R. Gallery and had mounted solo shows there,22 Zarina was not—her application had recently been rejected.23 She maintained, with good humor, that it was because her English was so good “they thought I was an upper-class Indian!” I interpret the inclusion of Zarina’s art in the show that she co-curated at A.I.R. Gallery as a gesture of defiance by the artist, as well as a show of solidarity by Mendieta and Miyamoto, who had voted to approve Zarina’s membership.24

Shortly after Mendieta graduated with an MFA from the University of Iowa, her work was included in Out of New York (1977), an A.I.R. Invitational show, which introduced her to a network of artists in the city before she moved there the following year.25 Within six months of relocating to New York City she joined A.I.R. Gallery and mounted her first solo show there, which was positively received. Her Silueta series consists of photographs of site-specific earthworks from Mendieta’s performances in Iowa and Mexico between 1973 and 1980, images that include her silhouette recessed into a verdant hill or the outline of Mendieta’s body after she laid in the earth.26 Within her first year of membership, Mendieta became frustrated with the organization and with US feminism.27 She began missing monthly meetings and even tried to sell her membership outright to Judy Blum, an artist whose application had also been rejected, evidence of Mendieta’s playful and rebellious nature.28 A.I.R. Gallery was willing to allow Third World to modify “woman” and “artist” in Dialectics of Isolation, but the organization was not willing to modify its mission statement to include women of color, nor to reconsider the terms by which they evaluated artists for membership or who sat on their board.29 “The white voice was the dominant voice,” Pindell observed of that time. “What the white male’s voice was to the white female’s voice, the white female’s voice was to the woman of color’s voice.”30 Ana Mendieta said it more succinctly: “They were cunts.”31

Imperial Feminism, Black Feminism and Third World Women Artists

Working together, the three friends shared the labor of the exhibition and used their platform to extend space and resources to other Third World women. Like most white women, these artists would never have had the chance to exhibit their work in male-dominated museums and galleries, but as nonwhite women they were also excluded from feminist art spaces, which white women dominated. Dialectics of Isolation included eight artists—Judith F. Baca, Beverly Buchanan, Janet Olivia Henry, Senga Nengudi, Lydia Okumura, Howardena Pindell, Selena Whitefeather,32 and Zarina—all Third World women, whose backgrounds included Chicanx, Black, Brazilian, Indigenous, and Indian.

Mendieta and Miyamoto were the only “women of color” in A.I.R. Gallery at the time of Dialectics of Isolation. The term was coined by Black organizers from Washington, DC, who were participating in a National Women’s Conference in Houston in 1977. This group of Black feminists wrote “The Black Women’s Agenda” (BWA) in response to a scant three-page “Minority Women’s Plank” that white organizers of the conference put together in an otherwise hefty two-hundred-page document. Other groups of nonwhite women at the conference, also disgruntled by their exclusion from the document, learned of the BWA and asked to contribute and be a part of it. The Black feminists agreed to include them, and through this alliance extended their agenda to include the needs and voices of other racialized women, creating “women of color” in the process. The phrase’s nascence embodied a commitment to multiracial solidarity and to listening and organizing around shared political agendas, not solely as a speech act but also to co-create a platform for sociopolitical struggle.33

The term was also used in the Combahee River Collective Statement, released the same year, which centered both Black women and coalition-building with other women of color to resist the interlocking oppressions of race, class, gender, and heterosexism:

We are a collective of Black feminists who have been meeting together since 1974. During that time we have been involved in the process of defining and clarifying our politics, while at the same time doing political work within our own group and in coalition with other progressive organizations and movements. The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face.34

Instead of women of color, Ana, Kazuko and Zarina, referred to themselves as Third World women, which situated them both in relation to one another—as migrants, exiles, and refugees whose struggles intersected with Black feminists in the United States35— and within an internationalist tricontinental framework of which they were also a part and which they used to draw other artists together.36

Zarina was part of the guest-editorial staff of “Third World Women: The Politics of Being Other,” a special issue of Heresies and an important precursor to the Dialectics of Isolation exhibition (fig. 6).37 The special issue took a year and a half to produce, and Zarina hosted the first meeting in her live-work studio in Chelsea’s garment district in what must have been early 1978. The guest-editorial collective included Lula Mae Blocton, Yvonne Flowers, Valerie Harris, Zarina, Virginia Jaramillo, Dawn Russell, and Naeemah Shabazz.38 Howardena Pindell, who contributed an essay to the issue, noted how Zarina was instrumental to its completion and echoed claims from the editorial statement, recalling that it was not easy to produce, due to tensions within the Third World women as well as between the guest collective and the Heresies collective.39 Zarina also curated an insert within the journal called “The Other Portfolio” (fig. 7) that included abstract works by Emmi Whitehorse, Virginia Jaramillo, Lula Mae Blocton, Zarina, Ann Page, and Li-Lan.40 The issue included Mendieta’s Silueta series and Beverly Buchanan’s (1940–2015) Ruins series (the latter was shown in Dialectics of Isolation) alongside written contributions by Third World artists, poets, and writers such as Joy Harjo, Betye Saar, Kay Walkingstick, Audre Lorde, and Adrian Piper, among others.

Contributors’ biographies were an impressively concise one to two lines long, unimaginable in our current professionalized art world: “Audre Lorde is a NYC Black lesbian feminist poet whose latest book is The Black Unicorn. The Poem ‘NEED’ is a dramatic reading for three women’s voices, based on recent murders in Black communities“; “Joy Harjo is a writer who lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She is of the [Muscogee] Creek tribe of Oklahoma, and teaches creative writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts”; “Zarina is an artist from India now living in New York City. She is a feminist committed to the rights of the Third World.”41 The range of topics touched upon in the issue is astounding: Pindell questioned the relationship between the art market and critics and the notion of “good taste”; Jane Quick-to-See Smith included poetic text alongside an image of her work; Valerie Harris interviewed Chris Choy about her work with Third World Newsreel and Camille Billops about the Hatch-Billops Collection and her interview with James Van Der Zee; and Adrian Piper wrote about her experiences being bullied by both white and Black people. The writing addressed racism, elitism, sexism, and homophobia; the forced sterilization of Indigenous and Chicanx women as well as kidnapping of children by the US government; the struggles between men and women and women and women; mothers in prison; Japanese internment camps; Chinese and Asian Exclusion Acts; the persistent stereotypes of Black women; wage disparities between Black and white people; and the exploitation of workers. The category of Third World shrank and expanded as needed, a liquid container for artists who identified in myriad ways but were all engaged in critiques of racial capitalism and invested in practices of decolonization.The editorial group for this special issue on “Third World Women” was racially and economically mixed, unlike the Heresies collective, which like A.I.R. Gallery was also overwhelmingly white and middle-class. The guest collective acknowledged the limits of representation and embraced alterity, offering a loose definition of themselves: “Third world women are other than the majority and the power-holding class, and we have concerns other than those of white feminists, white artists and men.”42 They introduced themselves in their editorial statement:

We are painters, poets, educators, multi-media artists, students, shipbuilders, sculptors, playwrights, photographers, socialists, craftswomen, wives, mothers and lesbians. In the beginning we were Asian-American, Black, Jamaican, Ecuadorian, Indian (from New Delhi) and Chicana; foreign-born, first-generation, second-generation and here forever. We are all of these and this is extremely hard to define.43

Lowery Sims’s essay “Third World Women” in Women Artists Newsletter recounts the first meeting of the Heresies guest collective. It began with Lula Mae Blocton inviting the artists to define “Third World women,” a challenging task. Artists instead shared the hardships they faced to find time to make artwork while working multiple jobs and caring for family, and the challenges of existing “on the lowest economic level,” noting that even when Third World women managed to enter a higher economic class, racism persisted. They observed that “black women had not benefited as much from the black movement as white women from the women’s movement.”44 Camille Billops, Sims reports, “warned against the wasteful preoccupation with the white male power structure and proposed that women infiltrate the establishment and exploit it to their advantage,” while Zarina cautioned against conflating women of color who live in the First World with the Third World, pointing out the disparity of access to technology and material resources in developed and developing countries. Sims responded: “although black American women may have relatively greater access to material resources, they share the political reality of other non-white women.”45

The discussion highlighted some of the tensions and misunderstandings that were alluded to in the editorial statement. It divulged how difficult it was to navigate the differences between the various Third World women who were a part of the guest editorial collective of Heresies, so much so that some left, while others insisted on the importance of working together despite differences. The collective asked questions such as: “Can working relationships be established and maintained between lesbian and heterosexual Third World women? Can Third World women afford to participate in volunteerism, since we have little, if any financial security as it is? Do we recognize that many of us actually practice feminist modes of being while rejecting them in theory?”46 The language of “otherness” found its way into the text of Dialectics of Isolation, as did the idea of forging solidarity through the “sameness of double racial/sexual oppression,”47 which was echoed by Mendieta when she wrote, “As non-white women our struggles are two-fold.”48

A Third Way

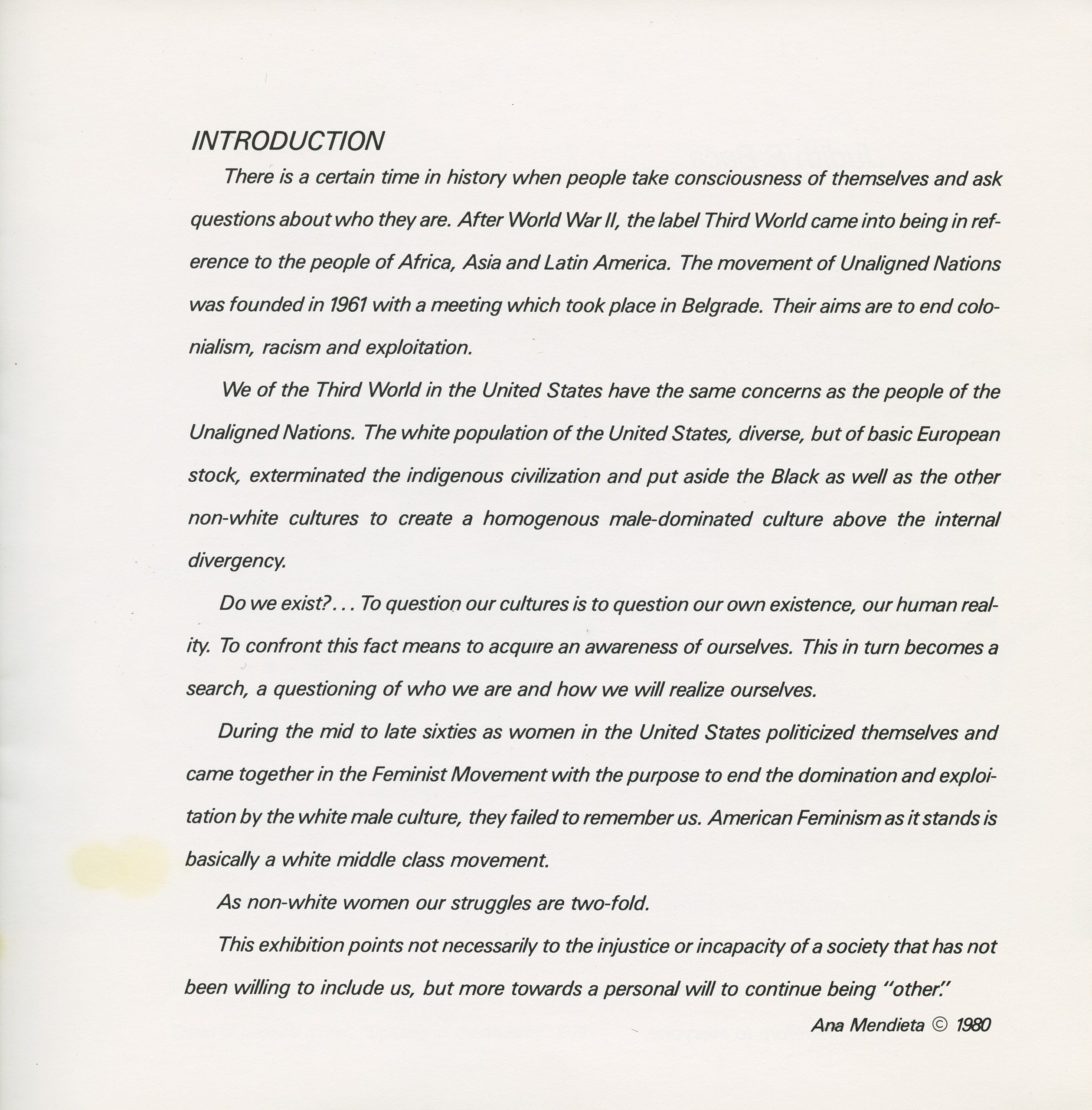

In the brief introductory text of the catalogue for Dialectics of Isolation, Mendieta unequivocally states that American feminism, to put it kindly, “failed to remember” Third World women. She situates the nascence of the term to 1961, with the founding of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Belgrade, composed of newly independent nations that refused to ally themselves with any world power or bloc and sought to end racism, colonialism, and exploitation. The artists in the exhibition are thus situated within this legacy of the NAM, which is juxtaposed against the provincialism of the US feminist movement:

We of the Third World in the United States have the same concerns as the people of the Unaligned Nations. The white population of the United States, diverse, but of basic European stock, exterminated the indigenous civilization and put aside the Black as well as the other non-white cultures to create a homogenous male-dominated culture above the internal divergency. . . . During the mid to late sixties as women in the United States politicized themselves and came together in the Feminist Movement with the purpose to end the domination and exploitation by white male culture, they failed to remember us. American Feminism as it stands is basically a white middle class movement.49

While Mendieta cites the meeting of the NAM from Belgrade in 1961, she does not mention its precursor, out of which the term in fact emerged. The nomenclature of the Third World arose in the wake of World War II, out of the Bandung Conference of 1955, also called the Afro-Asian solidarity movement, which was the first meeting of the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa.50 This was followed by a subsequent conference in Belgrade in 1961 (where Latin America was represented by Cuba, which joined after the revolution), and a third in Cairo in 1964. At the time of Dialectics of Isolation, the term “Third World” meant many things. In capitalist frameworks it was denigrating, used to describe a loose geographic territory as well as a temporality of capitalist development in which the Third World was belated, in a teleological development narrative led by the First World. In the United States, the term was also used to describe nonwhites in the 1970s, akin to the political term “Black” in Britain, which was then used to refer broadly to postcolonial migrants from regions formerly held by the British empire, before it fractured in the late 1980s. Third World was a broad anti-colonial category used by artists in the United States as an umbrella term for a range of racialized identities and sexual orientations.

Beyond these definitions and usages, Third World also denoted what Vijay Prashad, citing Frantz Fanon, called a “third way”51—a project and not a place—of other futures and imaginaries.52 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak bemoaned the fact that the third way “was not accompanied by a commensurate intellectual effort” in the “cultural field” beyond the simple binary of nationalism or anti-imperialism.53 Yet Third World women’s movements are largely ignored in such analyses, and it is here that I situate Dialectics of Isolation, propelling us beyond the limits of these old binaries as well as newer forms of majoritarian ethno-nationalism and neo-imperialism, toward the creation of “other” collectivities. Mendieta, Miyamoto, and Zarina extended nonaligned concepts such as anti-imperialism, antiracism, economic justice, and decolonization into what Muñoz describes as a logic of futurity,54 forging a “third way” among exiles, refugees, immigrants, and diasporic artists of color in New York City.

Dialectics of Isolation’s introductory text is a Third World feminist manifesto (fig. 8) that articulates a refusal of the politics of inclusion by staking a claim not only in anti-colonial and postcolonial movements of decolonization but also through what Édouard Glissant describes as the “right to opacity.”55 Glissant theorizes transparency as a demand placed upon the colonized by the colonizer in its attempt at comprehension of its minority subjects through comparison. He writes:

If we examine this process of “understanding” people and ideas from the perspective of Western thought, we discover that its basis is this requirement for transparency. In order to understand and thus accept you, I have to measure your solidity with the ideal scale providing me with grounds to make comparisons and, perhaps, judgments. I have to reduce.56

Mendieta’s text explicitly situates the show away from the white gaze and its demands for transparency and legibility through the insistence “towards a personal will to continue being ‘other.’”57 Selena Whitefeather Persico noted how visionary the exhibition was for its time, particularly its resistance to representations of exoticization, suffering, and abjection: “Too often what was presented as ‘other’ were voices of exclusion, anger, and suffering or clichés about exotica and nobility.”58 This refusal extended to a proclivity for abstraction in the work of artists like Buchanan, Nengudi, and Pindell, which differentiated them from their peers in the Black arts movement who were making politically legible, figurative work. About Nengudi, David Hammons observed: “No one would even speak to her [in Los Angeles] because we were all doing political art. She couldn’t relate. She wouldn’t even show around other black artists because her work was so ‘outrageously’ abstract. Senga came to New York and still no one would deal with her because she wasn’t doing ‘Black Art.’”59

Dialectics of Isolation is often discussed through identitarian frameworks rather than formalism, despite the artists’ shared affinities with Post-Minimalism, performance, and Land art. Beverly Buchanan, Howardena Pindell, Selena Whitefeather, Senga Nengudi, Lydia Okumura, and Zarina were invested in organic materials, environmentalism, corporeality, seriality, and labor-intensive, process-based feminist practices, yet they were largely excluded from art criticism and feminist and Post-Minimalist exhibitions at the time. Jennifer Burris and Park MacArthur take issue with Rickey’s critique of the divergence between form and politics in the show, or what they describe as the exhibition’s “sociopolitical ‘affinity’ and its formalist predilections”60 that are imbricated in form: “By expecting the political to announce itself as subject or object, critiques such as Rickey’s . . . fail to recognize the nuanced complexity of form, in which intensely subjective histories grounded in the politically informed worldview of the artist are manifest through minimal or abstract techniques.”61 Aruna D’Souza likewise observes that Rickey imposed a false opposition between abstraction versus representation and teases out other connections gained through the show’s curatorial framework.62

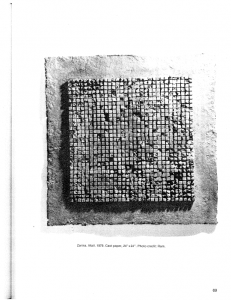

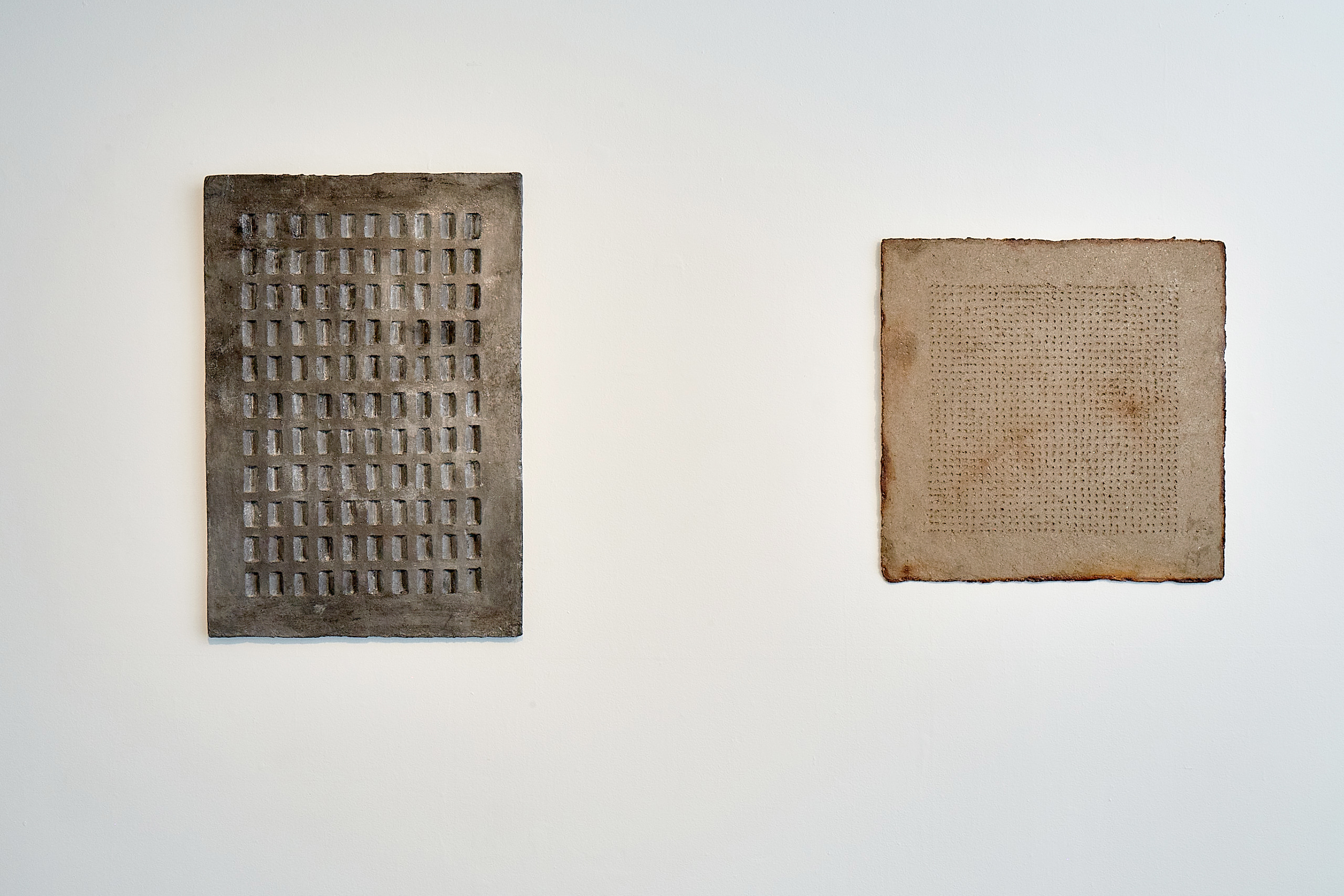

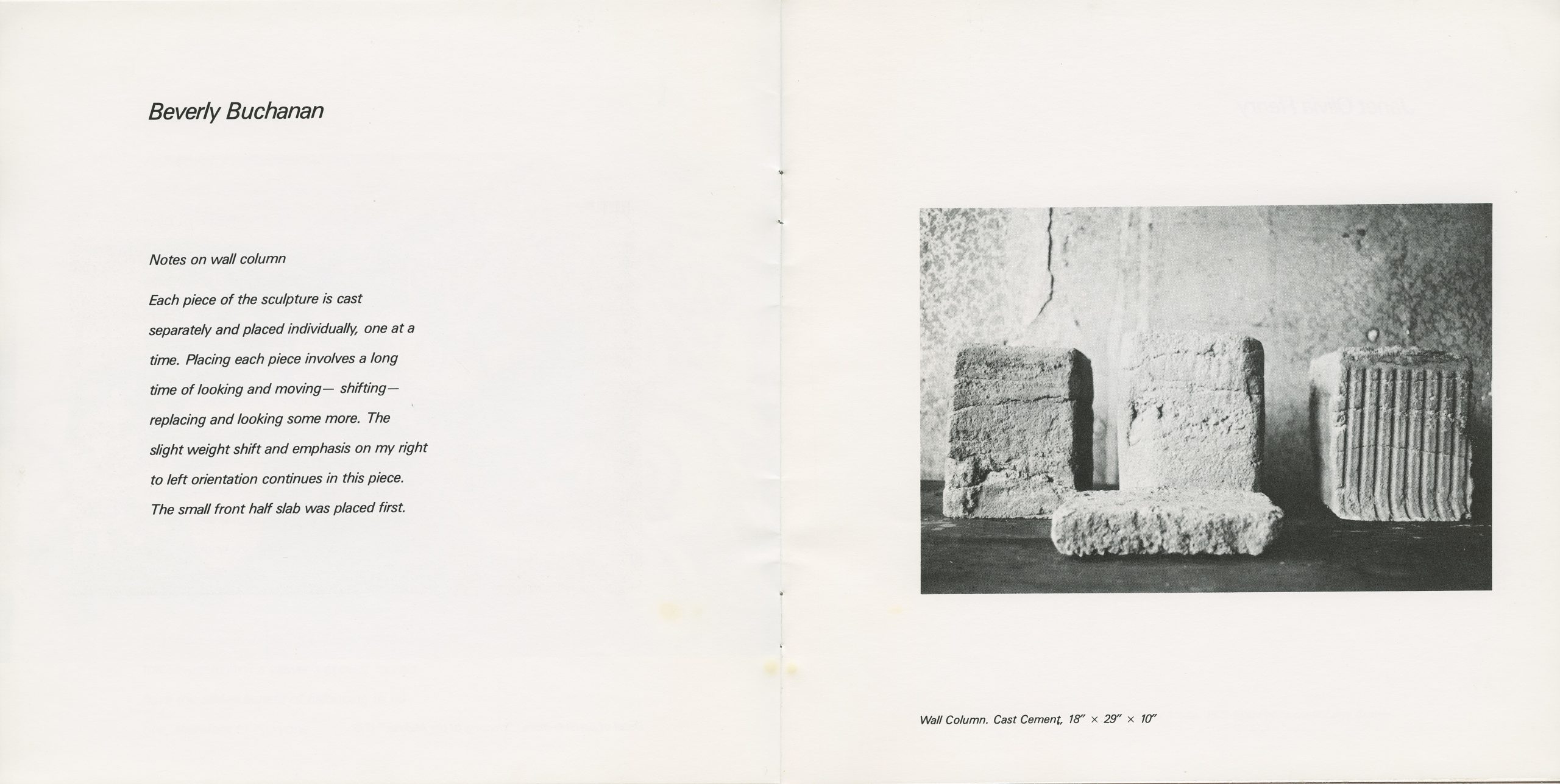

Zarina exhibited Corners (fig. 9) a shimmering gunpowder-gray rectangle with cubic recesses, which pulls together influences from Indian modernism and the Minimalist and Post-Minimalist movements in New York. Although the wall-hung sculpture appears heavy, as if it is concrete, it is very light, made from pulped handmade paper mixed with water, cast in a plastic mold and compressed, creating a bond from the pressure alone, without any adhesive. Its surface sheen was achieved from mixing powdered graphite into the pulped paper with a kitchen mixer.63 Beverly Buchanan’s sculptural installation Wall Column (fig. 10),64 like Zarina’s work, also bears traces of the process used to make it. It consists of four blocks of cast concrete tinted with iron oxide and acrylic paint, arranged carefully on the ground. The sculpture evokes architectural spolia and sedimented layers of geological strata. Rickey described Buchanan’s process as “a very sophisticated procedure for making what appear to be primitive artifacts . . . like the rocks of Stonehenge,”65 which perpetuates colonial epistemologies of sophisticated art versus primitive artifacts. Both Buchanan and Zarina’s small-scale works engage with architecture and space while refusing the large-scale monumentality of Minimalism, where the artists replaced scale with temporal engagement—viewers were asked to slow down and spend time with the work. All the artists also wrote about their works for the multivocal catalogue. Both Buchanan and Zarina’s texts read poetically; “Notes on wall column” details the process of Buchanan’s work, and Zarina’s untitled text gives insight into the influence on her work of the time she spent in Japan.

Nengudi’s Swing Low (1977) hung off of the ceiling and wall, the brown nylon pantyhose stretching from being pulled, pinned, and also weighted with sand; its two pendulum-like forms evoked the human body. Whitefeather’s Complete View of a Region in Every Direction (1980) included a slide projection of photographs of woody plants playing alongside audio of Whitefeather reading “Frothy masses on stems . . . large brown blotches . . . dark sooty areas near wounds . . . ,”66 a litany of botanical diseases that are part of a larger series by the artist on plant and animal life and their relationship to the land. The exhibition also included an installation by Lydia Okumura, who painted the floors and the walls, creating a geometric shape that produced an optical illusion disrupting the viewer’s perception of space, subtly intervening into the architecture of the gallery without adding any additional materials besides paint.

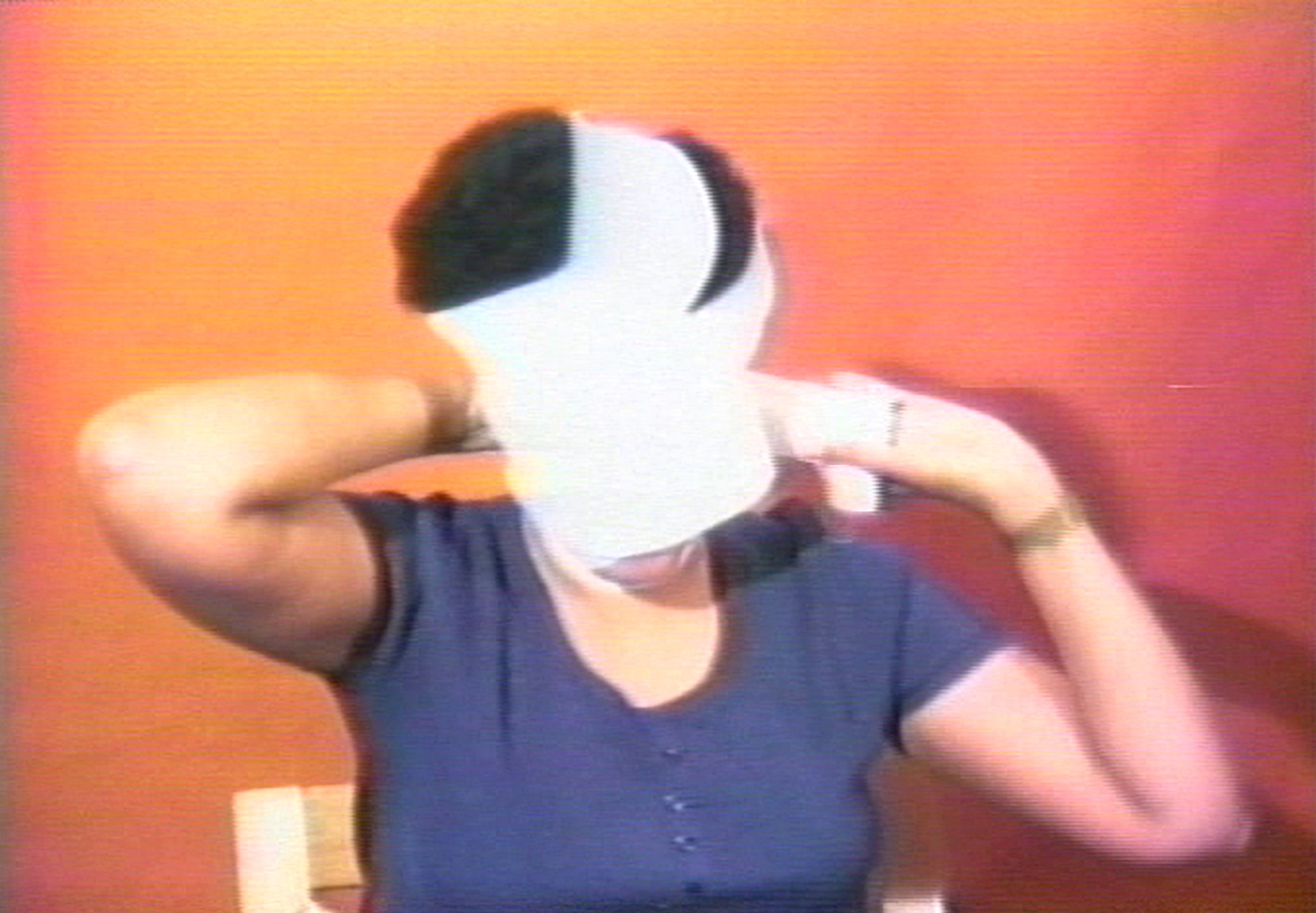

Janet Olivia Henry’s assortment of small objects (oars, clothing, a baseball bat, a briefcase) were placed upon a plinth in Juju Box for a White Protestant Male (1979–80), a playful rejoinder to racism that took the white man as its subject. The artist assembles miniature dollhouse-size replicas of his accoutrements, a kind of semiotics of the WPM, in which “each item represents a word, a clump of things together to make a sentence.”67 Portable segments of Judy Baca’s large, social realist mural Uprising of the Mujeres (1979) were also exhibited, and Baca’s catalogue text noted the importance of public art’s accessibility to broader segments of the population. Pindell’s controversial video work Free, White and 21 (fig. 11), which was a departure from her lush, colorful abstract paintings, premiered in Dialectics of Isolation, playing a central role in articulating the show’s dialectical critique of Euro-American feminism.68 In it, Pindell plays two characters, a Black woman who flatly recounts traumatic, intergenerational stories of racism that her mother and then she herself faced as children, and a white feminist who mocks, gaslights, and then threatens the Black woman. The video is alternately horrifying and amusing, with Pindell masking and unmasking her face repeatedly, with a white bandage and then a thin layer of adhesive that is peeled off of her skin. In the installation, the artist placed a metronome atop the video monitor,69 which ticked along with the sound from the video, creating two temporalities—of the body viewing the video and the other subsumed within it.

Although no photographs of the overall installation exist, nor of viewers in the space encountering the works, the relationships between the artwork in Dialectics of Isolation are apparent. The works gain meaning from their proximity to one another and rupture what Fred Moten calls the “geographical-racial exclusions”70 of Euro-American art-historical canons—feminism, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Land art. Interest in Dialectics of Isolation persists as a result of the strength of the curatorial framework, the artists’ individual works, and in the contemporary desire to retrieve marginalized histories of nonwhite artists whose work and embodiment in the 1970s and 1980s posited a threat to the hegemony of Euro-American feminism and North American histories of art.71

In 2018, A.I.R. gallery revisited Dialectics of Isolation, restaging it as Dialectics of Entanglement: Do We Exist Together? The curators, Roxana Fabius and Patricia M. Hernandez, describe their show as honoring and “being in conversation” with the original show by extending its concerns and translating identification with the Third World for current audiences to “identification with the struggles borne by Black Lives Matter, the immigrant rights movement, the Ni una menos movement, Indigenous Peoples dispossessed of their lands, the multiple forms of refugee crisis . . . the issues facing lesbian, trans, and other queer people, those living with disabilities.”72 It is an ambitious claim. Dialectics of Entanglement included original works, when available, and a publication with a curatorial text and commissioned essays by Aruna D’Souza and Rachel Rakes. The curators also reproduced written material from the old catalogue and placed them alongside new reflections by the artists on the work they had displayed thirty-eight years earlier. These ruminations by the now-septuagenarian and octogenarian artists are among the most promising and unfulfilled contributions of the show. One wishes the curators had conducted longer oral histories with the living artists, so that they might reflect upon topics such as the dissolution of the Third World women’s movement in the United States, the rise in usage of Asian American as a form of political solidarity, how US-led wars created today’s crises around migrants and refugees as well as the ongoing movement for Black lives; share their responses to the belated interest in many of the artists in the show who worked with abstraction; and ask the artists how they feel about the persistence of neocolonialism and white supremacy in Euro-American histories of art.

Cite this article: Sadia Shirazi, “Returning to Dialectics of Isolation: The Non-Aligned Movement, Imperial Feminism, and a Third Way,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11426.

PDF: Shirazi, Returning to Dialectics of Isolation

Notes

- Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States, curated by Ana Mendieta, Kazuko Miyamoto, and Zarina, A.I.R. Gallery, New York City, September 2–20, 1980. ↵

- Carrie Rickey, “The Passion of Ana,” Village Voice, September 10–16, 1980, 75. The review’s title is a play, presumably, on Ingmar Bergman’s The Passion of Anna (1969). Rickey also contributed writing to Heresies. ↵

- Kat Griefen, “Ana Mendieta at A.I.R Gallery, 1977–82,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 21, no. 2 (July 2011): 177–81. ↵

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Against the Body: Interpreting Ana Mendieta,” in Ana Mendieta: Traces, ed. Stephanie Rosenthal (London: Hayward Publishing, 2014), 27–37. ↵

- Bryan-Wilson, “Against the Body,” 31, referencing Gloria Orenstein’s essay in “The Great Goddess,” special issue of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics (January 1, 1978). ↵

- Jane Blocker, “Ana Mendieta and the Politics of the Venus Negra,” Cultural Studies 12, no. 1 (1998): 31–50; Coco Fusco, “Traces of Ana Mendieta, 1988-1993,” in English is Broken Here: Notes on Cultural Fusion In The Americas (The New Press: New York City, 1995): 121-125. ↵

- Ana Mendieta, press release for the exhibition Ana Mendieta: Esculturas Rupestres—Rupestrian Sculptures, A.I.R. Gallery, New York City, November 10, 1981, in Bryan-Wilson, Ana Mendieta, 212; Ana Mendieta, “La Venus Negra, based on a Cuban legend,” in Lyn Blumenthal et al., eds., “Earthkeeping/Earthshaking: Feminism & Ecology,” Heresies: A Feminist Publication of on Art and Politics 4, no. 1 (1981): 22. Mendieta was part of the guest-editorial collective, along with Lyn Blumenthal, Janet Culbertson, Shirley Fuerst, Sandy Gellis, Phyllis Janto, Sarah Jenkins, Ellen Lanyon, Lucy R. Lippard, Jane Logemann, Sabra Moore, Linda Peer, and Merle Temkin. ↵

- José Esteban Muñoz, “Vitalism’s after-burn: The Sense of Ana Mendieta,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 21, no. 2 (2011): 191–98. ↵

- Fusco, “Traces of Ana Mendieta, 1988–1993,” 121. ↵

- Throughout this essay I refer to the three artists either by their surnames, per convention, or their first names, in order to retain the intimacy by which they referred to one another during our interviews. Kazuko, like Zarina, went solely by her first name in the 1970s and 1980s, a feminist gesture that refused patriarchal naming conventions. She only later began using her surname of Miyamoto, and so she would be known by her peers from that time by only her first name. ↵

- Mendieta arrived to the United States in 1961 at the age of twelve with her elder sister Raquelin Mendieta, who was fifteen. Her family in Cuba was well-to-do, and her father, a politician, had taken part in the CIA-led Bay of Pigs invasion against Castro and was imprisoned in Cuba when it failed. She and her sister were placed in a Catholic orphanage run by nuns in Iowa and both learned English after they arrived. Linda Montano, “An Interview with Ana Mendieta,” Sulfur Magazine 22 (Spring 1988): 65. ↵

- Jonas Mekas, Jerome Hill, P. Adams Sitney, Peter Kubelka, and Stan Brakhage opened Anthology Film Archives in 1970. After Hil’s death, it shifted to Fluxus and moved to 80 Wooster Street. ↵

- There was no sliding-scale structure for fees that accommodated variable factors like single versus married women, or to compensate for individual and intergenerational class differences. Howardena Pindell in conversation with the author, October 31, 2019. ↵

- Pindell worked first at the International and National Circulating Exhibitions Department and later as associate curator of prints and illustrated books at MoMA. Pindell left the organization because she could no longer afford its fees. Howardena Pindell in conversation with the author, October 31, 2019. ↵

- Luca Cerizza, “The Gallerist: Kazuko Miyamoto from A.I.R. Gallery and Onetwentyeight, New York,” Art Agenda Reviews, June 8, 2015, https://www.art-agenda.com/features/237394/the-gallerist-kazuko-miyamoto-from-a-i-r-gallery-and-onetwentyeight-new-york. ↵

- Cerizza, “The Gallerist.” ↵

- Lawrence Alloway, “Kazuko,” in Kazuko Miyamoto (Berlin: Exile Berlin, 2013): 14. ↵

- Zarina’s father was a professor at Aligarh Muslim University, and her mother was in purdah, which means that she was educated by teachers within the home and that she did not work outside of it. Zarina was educated in Urdu medium schools and received a degree in mathematics from Aligarh Muslim University. See Sadia Shirazi, “Feminism for Me Was About Equal Pay for Equal Work—Not About Burning Bras: Interview with Zarina,” MoMA Post, March 8, 2018, https://post.moma.org/feminism-for-me-was-about-equal-pay-for-equal-work-not-about-burning-bras-interview-with-zarina; and Lisa Liebmann, “Zarina Hashmi: Visual Artist,” Artist & Influence (New York: Hatch-Billops Collection, 1991): 63–74. ↵

- Zarina also met fellow Indian artist Krishna Reddy in Paris at Atelier 17, where he was assistant director. He and his wife, the artist Judy Blum, moved to New York City in the mid-1970s and remained lifelong friends with Zarina. Judy Blum in conversation with the author, September 6, 2019. ↵

- A few years after Zarina migrated to New York from New Delhi, her husband, from who she was separated, passed away from cardiac arrest in India. Although she was entitled to a pension from the Indian government as a widow of a member of the foreign service, she could only receive it if she lived in India. Zarina decided to forego the pension and remain in New York, facing great financial hardship during this period of her life. Zarina in conversation with the author, February 4, 2018. ↵

- The guest editorial collective included seven “Third World women” artists: Lula Mae Blocton, Yvonne Flowers, Valerie Harris, Zarina Hashmi, Virginia Jaramillo, Dawn Russell, and Naeemah Shabazz. Zarina was the only Asian American and identified as “Indian” at the time (while both she and Naeemah Shahbazz were Muslim, neither artist mentions that within their biographies nor are there essays that deal with it as a category of identification). The nomenclature of South Asia had also not yet emerged as an identity category for the diaspora that arrived from across the subcontinent after the enactment of the 1965 Immigration Act. After the destruction of the Babri Masjid in India in 1992, Zarina began to identify as Muslim, and after 9/11, in the United States, she was further identified with it by others due to the racialization of non-Black Muslims. See Lula Mae Blocton et al., eds., “Third World Women: The Politics of Being Other,” special issue of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, 2, no. 4 (1979): 1; Sadia Shirazi, “Feminism for Me Was About Equal Pay for Equal Work—Not About Burning Bras: Interview with Zarina,” MoMA post, March 8, 2018, https://post.moma.org/feminism-for-me-was-about-equal-pay-for-equal-work-not-about-burning-bras-interview-with-zarina. ↵

- Mendieta and Miyamoto both left the gallery in 1982. Mendieta was a member for four years, from 1979 to 1982, and Miyamoto was a member for eleven years, from 1972 to 1982. ↵

- Zarina in conversation with the author, September 15, 2016. ↵

- In my conversations with Kazuko Miyamoto and Zarina, they also described close friendships with particular individuals who were supportive of women of color within the organization and across the feminist movement, such as Nancy Spero. Kazuko Miyamoto in conversation with the author, October 11, 2019; Zarina in conversation with the author, February 4, 2018. ↵

- Exhibition invitation for Out of New York, May 28–June 28, 1977, the A.I.R. Gallery Archive, MSS 184, box 10, folder 406, New York University Libraries; Ana Mendieta, unpublished statement,’ 1977, the A.I.R. Gallery Archive, MSS 184, box 10, folder 406. ↵

- The artist also organized screenings of her films as part of the gallery’s evening events. ↵

- Ana Mendieta, “Introduction,” in Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women of the United States, exh. cat. (New York: A.I.R. Gallery, 1980): 1. ↵

- Mendieta tried to sell her membership to the artist Judy Blum, who decided against the purchase while appreciating the humor of the situation and Mendieta’s frustration with the membership selection process at A.I.R. Gallery. Blum mentioned that Nancy Spero kindly reached out to her afterward to voice her frustration regarding Blum’s rejection. Judy Blum in conversation with the author September 6, 2019, and April 6, 2021. See also Ana Mendieta’s resignation letter, October 19, 1982, the A.I.R. Gallery Archive, MSS 184, box 11, folder 440. ↵

- A.I.R. Gallery had a “Task Force on Discrimination Against Women and Minority Artists.” Griefen, “Ana Mendieta at A.I.R. Gallery, 1977–82,” 173. ↵

- Howardena Pindell, “Free, White and 21,” in “Autobiography, ” special issue of Third Text 6, vol. 19 (1992): 31. ↵

- Judy Blum in conversation with the author, September 6, 2019. ↵

- Later Selena W. Persico. ↵

- The Third World Women’s Alliance was a socialist organization founded in New York City that first began as the Black Women’s Liberation Committee (BWLC) in 1968, a caucus of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). See Stephen War, “Third World Women’s Alliance,” in Peniel E. Joseph, ed., Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights-Black Power Era (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), 141; Western States Center, “Loretta Ross: The Origin of the Phrase ‘Women of Color,’” YouTube video, 2:59, February 15, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82vl34mi4Iw&feature=emb_title. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, “A Black Feminist Statement” in Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, ed. Zillah Eisenstein (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1978): 210-218. ↵

- For more on Black and Third World feminist thought around global capitalism and decolonization, see Brenna Bhandar and Denise Ferreira da Silva, “White Feminist Fatigue Syndrome,” Critical Legal Thinking, October 21, 2013, https://criticallegalthinking.com/2013/10/21/white-feminist-fatigue-syndrome. Thanks to Constantina Zavitsanos for bringing this writing to my attention. ↵

- Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) is another example of the translation of the principles of the Non-Aligned Movement into the diaspora. TWLF was created as a coalition of multiracial, anti-imperial student groups at San Francisco State University and the University of Berkeley who organized strikes to challenge admissions practices that excluded nonwhite students. Their request to establish a Third World College went unrealized, although protests resulted in the establishment of departments of Ethnic Studies, including Black and Asian American Studies. Harvey Dong, “Third World Liberation Comes to San Francisco State and UC Berkeley,” Chinese America: History and Perspectives, (2009): 95–106, 157; Victoria Wong, “Cultural/Political Activism and Ethnic Studies (1969–2019),” Ethnic Studies Review, 42, no. 2 (fall 2019): 151–57. ↵

- Lula Mae Blocton et al., eds., “Third World Women: The Politics of Being Other,” special issue of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics 2, no. 4 (1979). ↵

- Zarina’s marital surname was Hashmi, although she stopped using it in exhibitions after returning to New Delhi from Paris in 1968, when she separated from her husband. Zarina in conversation with the author, September 15, 2016. ↵

- Howardena Pindell in conversation with the author, October 31, 2019. ↵

- Blocton, “Third World Women,” 66–71. ↵

- Blocton, “Third World Women,” 123. ↵

- Blocton, “Third World Women,” 1. ↵

- Blocton, “Third World Women,” 1. ↵

- Lowery Sims, “Third World Women,” Women Artists Newsletter 4, no. 6 (December 1, 1978): 10. It bears mentioning that a series of exhibitions organized by Black women in New York City preceded Dialectics of Isolation and the Third World women’s art and activism. These include the remarkable “Where We At” Black Women Artists: 1971 at the Acts of Art Gallery and 11 (1975), curated by Faith Ringgold at the Women’s Interarts Center in New York. The Where We At show was curated by Nigel Johnson in his West Village gallery and led to the subsequent formation of the collective “Where We At” Black Women Artists Inc. (WWA). The artists in Where We At included Dindga McCannon, Kay Brown, Faith Ringgold, Carol Blank, Jerri Crooks, Charlotte Kâ (Richardson), and Gylbert Coker, among others. Valerie Smith, “Abundant Evidence: Black Women Artists of the 1960s and 1970s,” in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Cornelia Butler and Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 400–13; Kay Brown, “The Emergence of Black Women Artists: The Founding of ‘Where We At,’” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 29 (Fall 2011): 118–27; Faith Ringgold, “Bio & Chronology,” Faith Ringgold, News, Appearances, Exhibitions, Permissions and Projects, accessed November 1, 2019, http://faithringgold.blogspot.com/2007/03/bio-chronology.html. ↵

- Sims, “Third World Women,” 10. ↵

- Blocton, “Third World Women,” 1. ↵

- Blocton, “Third World Women,” 1. ↵

- Mendieta, Dialectics of Isolation, 1. ↵

- Mendieta, Dialectics of Isolation, 1. ↵

- The conference was organized by Indonesia, Burma (Myanmar), India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and Pakistan. Participants included China, Yemen, Iraq, the Gold Coast, Afghanistan, Japan, and Libya. ↵

- Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: The New Press, 2007), xv. This is not the “third way” as a triangulation, as it would soon be articulated by neoliberalism during the Clinton years, nor is it the centrism of Blair in Britain. A special thank you to Mezna Qato for this insight. ↵

- The Third World Gay Revolution (T.W.G.R.) was another organization based in New York City whose manifesto was included in a 1971 issue of the gay liberation journal. Titled “What We Want, What We Believe,” the manifesto included demands for the abolition of capital punishment, institutional religion, and the bourgeois family, as part of what was described as a new, revolutionary, socialist society. Muñoz contends that the Third World Gay Revolution’s “‘we’ does not speak to a merely identitarian logic but instead to a logic of futurity.” José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 19. See also Weiyi Chang, Sofia Jamal, Colleen O’Connor, and Patricio Orellana, After La vida nueva, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2020), 63, 65, 97. ↵

- Mahasweta Devi, Imaginary Maps: Three Stories, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (New York and London: Routledge, 1995): xxv–xxvi. The quotations are taken from Spivak’s “Translator’s Preface.” ↵

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 20. ↵

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). ↵

- Glissant, Poetics of Relation., 189–90. ↵

- Mendieta, Dialectics of Isolation, 1. ↵

- Selena W. Persico, “Selena W. Persico,” in Dialectics of Entanglement: Do We Exist Together?, ed. Roxana Fabius and Patricia M. Hernandez (New York: A.I.R. Gallery, 2018), n.p. ↵

- Begum Yasar, “Foreword,” Senga Nengudi (New York and London: Dominque Levy, 2015), 13. ↵

- Jennifer Burris and Park MacArthur, Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals (Mexico City: Athénée Press, 2015), 15. ↵

- Burris and MacArthur, Beverly Buchanan, 15–16. ↵

- Aruna D’Souza, “Curating Difference,” in Fabius and Hernandez, Dialectics of Entanglement: Do We Exist Together?, n.p. ↵

- Zarina in conversation with the author, September 15, 2016. ↵

- This work was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art from the show. Griefen, “Ana Mendieta at A.I.R Gallery, 1977–82,” 175. ↵

- Rickey, “The Passion of Ana,” 75. ↵

- Rickey, “The Passion of Ana,” 75. ↵

- Janet Olivia Henry, Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States, exh. cat. (New York: A.I.R. Gallery, 1980). ↵

- The video work included a metronome atop the monitor playing the video. Howardena Pindell in conversation with the author, October 31, 2019. ↵

- Howardena Pindell in conversation with the author, October 31, 2019. The original catalogue notes that the work consists of a video and metronome. ↵

- Fred Moten, In the Break: Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 31. ↵

- The exhibition Soft and Wet attempted to intervene in this erasure of anti-imperial and Third World gay and feminist movements from feminist histories of art and activism. It functioned as an exhibition within an exhibition—with Dialectics of Isolation at its center—and brought three artists from the Third World movement who identified as women together with contemporary artists whose work the curator situated within its legacy. Soft and Wet, curated by Sadia Shirazi and presented at theElizabeth Foundation for the Arts, Project Space Gallery, New York City, September 18–November 16, 2019; Sadia Shirazi, “Preface to an Exhibition,” and Jeannine Tang, “Holding Space: Julie Tolentino between Ana Mendieta and Zarina” in Sadia Shirazi, ed., Soft and Wet, exh. cat. (New York: Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, 2019); and Natasha Marie Llorens, “Soft and Wet,” Art Agenda Reviews, November 13, 2019, https://www.art-agenda.com/features/300642/soft-and-wet. The exhibition After La vida nueva also revisited the Third World movements in New York City in the 1980s. After La vida nueva, curated by Weiyi Chang, Sofia Jamal, Colleen O’Connor, and Patricio Orellana, hosted online by Artists Space, August 7–August 31, 2020. ↵

- Roxana Fabius and Patricia M. Hernandez, Dialectics of Entanglement: Do We Exist Together? (New York: A.I.R. Gallery, 2018), n.p. ↵

About the Author(s): Sadia Shirazi is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Art History and Visual Studies, Cornell University