Un-Disciplining the Archive: Jerome Reyes and Maia Cruz Palileo

In the large painting They Dreamed in English (fig. 1) by Maia Cruz Palileo (b.1979), a brightly lit classroom stands vacant. An easel on the teacher’s desk, scattered books, and friezes of illustrated flora and fauna suggest that art is learned here. Dark wall panels reveal silhouettes of students, suggesting the interstitial time between class periods when these spaces—typically full of chatter and energy—are eerily quiet. The emptiness is thick with references to prior inhabitation and the room’s own spatial fictions: the ceiling opens to a yellow-teal sky, the timber framing following an inchoate structural logic; the floor, a radiant and colorful hallucination of pinks, oranges, and aquamarine, reveals an alternative world of dark-faced figures that loosely mirrors that of the classroom. This dreamlike space brings us back to the work’s title, They Dreamed in English, wherein something learned, often foreign, eventually seeps into the unconscious.

“The most effective means of subjugating a people,” wrote historian Renato Constantino in 1970, “is to capture their minds. Military victory does not necessarily signify conquest.”1 Restructuring the public education system was central to colonial policy in the aftermath of the Philippine-American War of 1899. US forces confronted a recalcitrant people who had resisted Spanish colonial rule for the better part of a century. What we do not know about the war—the exact number of Filipino soldiers and civilians killed, maimed, or tortured—haunts the archival record.2 The relative invisibility of the war in American public memory is surprising given its foundational role in the US imperial era, and it represents a crucial and inescapable aporia within which Filipino American culture has been forged. Educational reform—instilling American values and language—was an effective tool of colonial domination because it worked from the inside out, producing learned inferiority and cultural indoctrination that could shape generations. Homi Bhabha later theorized this “colonial mimicry,” or “the desire for a reformed, recognizable Other” as “constructed around an ambivalence; in order to be effective, mimicry must continually produce its slippage, its excess, its difference.”3 Returning to Palileo’s painting, we understand the past tense of the title, the disciplinary appearance of the room, and its melancholic tone as signs of a colonial education well underway. Its figures may not be silhouettes but rather shadowy refractions of the miseducated.

Filipino immigrants to the United States in the early twentieth century who sought US citizenship were rebuffed as “simultaneously immigrant and colonized national,” or “foreign in a domestic sense.”4 This legal ambiguity reflects the ambivalence with which Asians have long been received in the United States (ambivalence is the coexistence, in one person, of conflicting or profoundly opposing attitudes toward another person or thing).5 They are encouraged to assume a value system that denies them full rights and citizenship, expected to assimilate while cast as unintelligible and perpetually alien, and interpellated into racial hierarchy while deracinated under the myth of the “model minority.”6 And yet, as Lisa Lowe argues, the ambivalence toward the Asian immigrant “produces alienations and disidentifications out of which critical subjectivities emerge. These immigrants retain precisely the memories of imperialism that the US nation seeks to forget.”7 For Filipinos in the United States, the history of colonial encounter is suppressed from the record, even as it remains foundational to the racializing process of defining American (citizen) against Asian (immigrant).

Asian American history follows a cascading timeline of exclusionary orders, immigration quotas, and forced movements entangled with broader histories of colonialism and settler colonialism, slavery, and other campaigns waged against persons considered inferior to those of European descent. These differences in common render Asian American cultural identity—which remains undertheorized—as one of unfolding contradictions.8 For Asian American artists, who share no unifying identity other than their discrepant ethnicity vis-a-vis whiteness, there are many shared moments of racial formation, which sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant define as “the sociohistorical process by which racial identities are created, lived out, transformed, and destroyed.”9

This essay focuses on two Filipino American contemporary artists who recruit ambivalence as a conceptual tool to undiscipline the authority of the colonial apparatus. Jerome Reyes (b. 1983) and Maia Cruz Palileo remediate the colonial past through the means of its official construction (photography, oral histories, and other archival practices), proposing a future in which the formerly suppressed structures of colonialism and imperialism are made known but cannot be erased.

⸹

Art history has publicly grappled with its imperialist and colonial roots for some time, and recent calls to decolonize the field and its infrastructures seek to expose, and perhaps untether, its foundations in Eurocentric thought.10 Of the many ensuing debates about restitution and inclusion, the most germane to a discussion of Asian American art is whether to absorb its historically marginal figures into the canon of American art or to decenter the canon itself—in other words, to lay more bricks or to rebuild the house. As Christopher Green argued recently in Art in America, “inclusion alone is not decolonization.”11 Integrating marginalized cultural objects and artists into national frameworks may disrupt the canon, but those efforts often stop short of altering the value systems around which the very conception of American art and American nationalism was constructed. There are advantages to differentiation; for example, the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, and Black Studies not only created crucial worlds in which African American artists could flourish but also legitimized their work as an essential body of knowledge. This logic of distinction will be necessary, in the words of artist Lorraine O’Grady, “until black genius is accepted without condescension.”12

By embracing critical race studies as a cornerstone of American cultural study, we can see more clearly how US imperial history has shaped its cultural landscape, and how we might effectively reorient our disciplines. The concept of the Archipelagic Americas within American Studies, for example, is a postexceptionalist formation structured around American colonialism and its imperial island territories (extending the concept of Manifest Destiny from a landed concept to a global seagoing one)—a framework in which the Philippine-American War becomes a major story rather than a minor note.13 Recent scholarship in American art has moved to interrogate its nationalist ideals, questioning what and who American history involves, where it lives, and how it hides from itself. Race, as Omi and Winant argue, “is a fundamental axis of social organization” in the United States.14 I understand race not as a personal trait held by the marginalized but rather as a shifting historical structure that is central to settler colonialism and international colonialism, and which continues to structure economic inequality and distributions of power in the United States. This perspective aligns with the work of Critical Race Art History, a still-nascent field of study that engages deeply with comparative ethnic studies, a theoretical field that is rarely touched by art historians.15 Critical Race Art History is interdisciplinary, comparative, and methodologically driven to understand how visual representation shapes the construction of race in the past and how it makes meaning in the present. Exemplary interventions in this vein come from scholars like Jacqueline Francis, ShiPu Wang, Jennifer A. González, and others whose work illuminates how art history and criticism make race known—make it real—while also engaging fulsomely with art objects rather than reducing them to vague indices of “racial expression.”16

Within the art world, the very circumstances that make visible the work of Asian American artists also threaten to fix it as “a site of reconciliation and containment,” as art historian Susette Min asserts.17 Global art markets value artistic world-making that transcends “obsolete” categories of identity and nationhood, celebrating the multiplicity and connectedness of cosmopolitanism. Yet they readily exploit the pan-ethnic artistic brand and the ethnic/racially specific exhibition to bolster the art world’s appearance of inclusivity, in which the nomenclature of “Asian American” functions as a tool of neoliberal multiculturalism.18] These circumstances, Min argues, produce a condition of “disquieting ambivalence” for those who are familiar with the political and institutional conditions of racial exclusion from the art world that led to demands for the ethnic/racially specific exhibition. Min defines Asian American art not as a set of objects but rather as a critical hermeneutic, a negative dialectic, an object of knowledge, and a discursive experimental space that establishes the conditions of a politics to come.19 It is an arena of contingency, in other words, that finds its partner in the unknown future, and within which ambivalence—that byproduct of the colonial enterprise—can signal possibility.

Pursuant to Min’s call, my discussion foregrounds how Filipino American racial formation emerges as a conceptual driver of the work in ways that are not visually evident.20 Race is never the only axis of social formation but is nonetheless a crucial determinant of culture, and I hope to sidestep the double bind faced by Asian American art history as ostensibly present within yet beyond the scope of American art history. As Sarita See observes, the contradictions of Filipino American political identity—as a simultaneously assimilable and inassimilable vestige of US imperialism—lay the groundwork for artistic practices rooted in absurdity, dark humor, and code-switching as survival strategies. The work discussed here resists the invisibilizing effects of colonial amnesia through tactics of cultural presence and indirection, and by privileging ambiguity in the face of a white gaze that desires to fix the subject in its proper place.21

Jerome Reyes

Jerome Reyes creates long-term, multiplatform engagements that honor literal and symbolic sites of Asian American racial formation. His conceptually oriented practice revisits the legacy of the long 1960s—supported by oral history and archival research—through drawings, sculptural installations, video, and language-based public artworks.

Contact Points (2006–present) illuminates the cross-racial solidarity and intergenerational collaboration within Third World and Asian American activist histories. It began with an exhibition of Reyes’s work at the former site of the International Hotel (I-Hotel) in San Francisco’s Manilatown, home to many Filipinos and a key site of the Asian American movement. The project’s most recent iteration, Contact Points: Field Notes towards Freedom (2006–present), is a vast archive of Asian American history compiled with Seoul-based scholar tammy ko Robinson, located at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea.22 Reyes’s work with archives began in 2001 with Daniel Phil Gonzales, an original student striker at San Francisco State College (later University), who cofounded the nation’s first School of Ethnic Studies there in 1969. Reyes’s studio houses the bulk of Gonzales’s archive: the radical pedagogy and student-designed curricula that resulted from the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) strikes of 1968 in the Bay Area.

A decade after the strikes, threats to evict the elderly, low-income Filipino residents at the I-Hotel in 1977 galvanized the largest coalition group to date—including Yellow Power, the Black Panther Party, the American Indian Movement, and the TWLF—in a three-thousand-person human chain around the building. Ultimately destroyed and relocated, the I-Hotel survives as a community center and affordable housing facility for seniors where, in 2010, Reyes installed the exhibition Until Today: Spectres for the International Hotel.23 Reyes salvaged over one ton of bricks from the original site, including brick dust, which he used to create the installation Routes and Seasons (After Carlos Villa’s Quilt of Hope), whose rug of brick dust–coated bird feathers maps the exact 8-by-8-foot footprint of one of the I-Hotel’s residential rooms (fig. 2). An act of literal recovery and an homage to Reyes’s mentor Carlos Villa, the work—like other objects in the exhibition—represents a space of suggestive vacancies. In commemorating a history marked by its intense corporeality (the human chain of protestors, the physical extraction of elderly tenants from their homes by police), the works of art keep the viewer at a distance in the form of ambivalent structures: the ephemeral architecture of the rug, precise but nonspecific drawings of empty corridors, and the skeletal framework of a device used to measure carry-on luggage, constructed only of folded vellum. Corporeality returns by proxy in Analgesia (and Armament), projected monumentally onto the gallery’s floor. The video shows the hands of anti-eviction leader Dr. Estella Habal, who was in her late twenties during the protests, reenacting a moment immediately before the breach of the I-Hotel by police. In that historical moment, community leader Wahat Tampao took out a butterfly knife and distributed melon to his neighbors, offering nourishment and calm with a ritual significance. In the video, Habal’s knife retraces his movements, methodically slicing the juicy melon and cleaning out its guts, every “thunk” of the knife on the wooden board a sonification of analgesia, or the inability to feel pain, as armament.24

Another ongoing project, Contact Points: Field Notes towards Freedom, gathers a collection of ephemera and artifacts, donated by more than forty individuals and organizations, that materialize intergenerational and transnational legacies of Asian American activism. Described by the artist as “a curriculum of freedom written by Asians in migration,” the archive includes materials such as the University of California Berkeley curricula that influenced architectural thought in Taiwan; Philippine activist-scholar Walden Bello’s books on land and food rights; and Daniel Gonzales’s student identification card from San Francisco State, among other unique artifacts.25 It accumulates rhizomatic nodes of solidarity and survival such as the community center, Third World college, community housing, Asian arts complex, solidarity bookstore, sanctuary and clinic, and lending library, a reminder that radical thought takes quotidian forms. As the artist reflects, “one can’t fully separate the music from the time period in which it happened; one can’t split the community programs and health programs away from housing issues; one can’t remove the presence of comic books, literature, and poetry from the labor and student strikes that were happening. They are all lived through the same people.”26

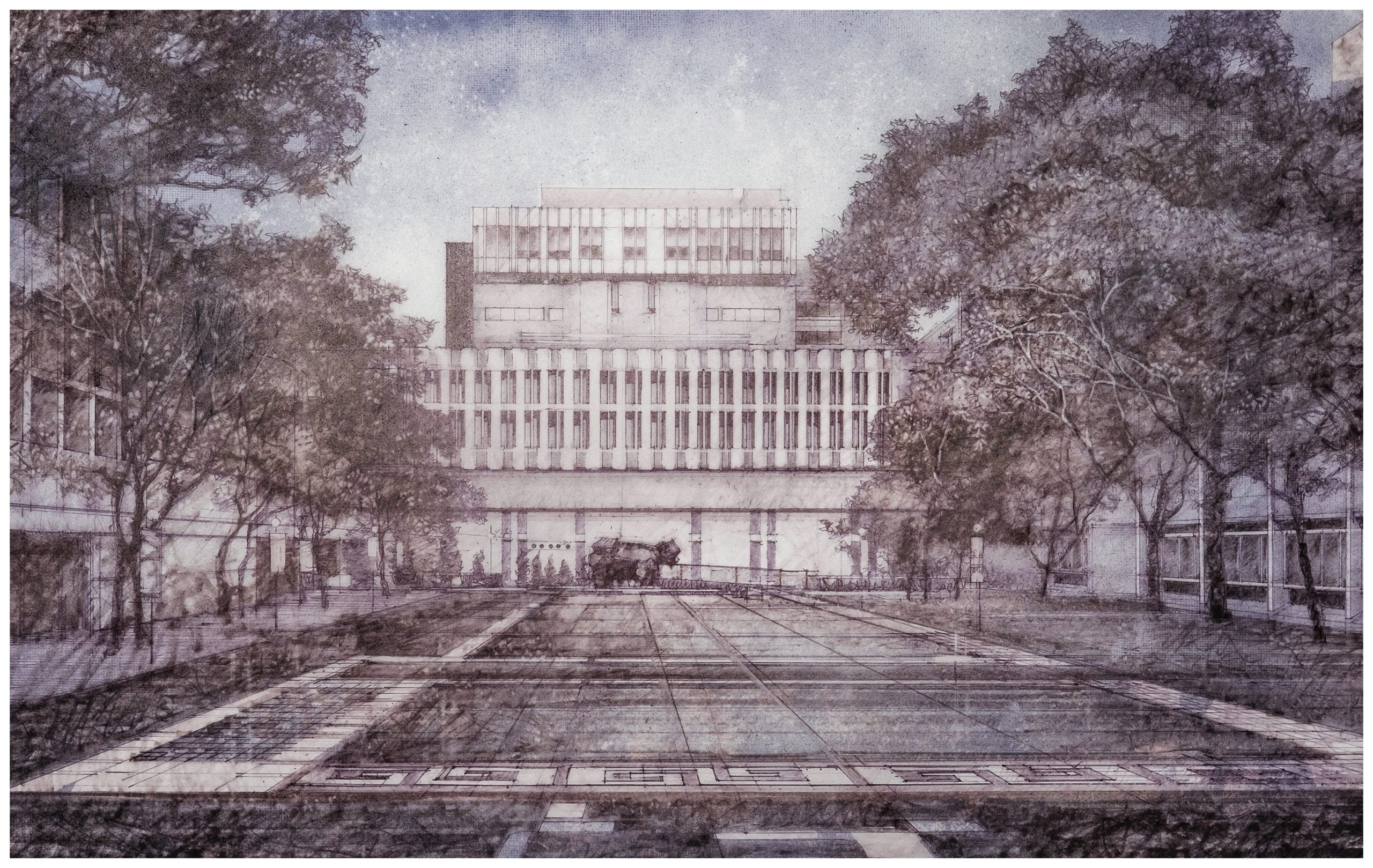

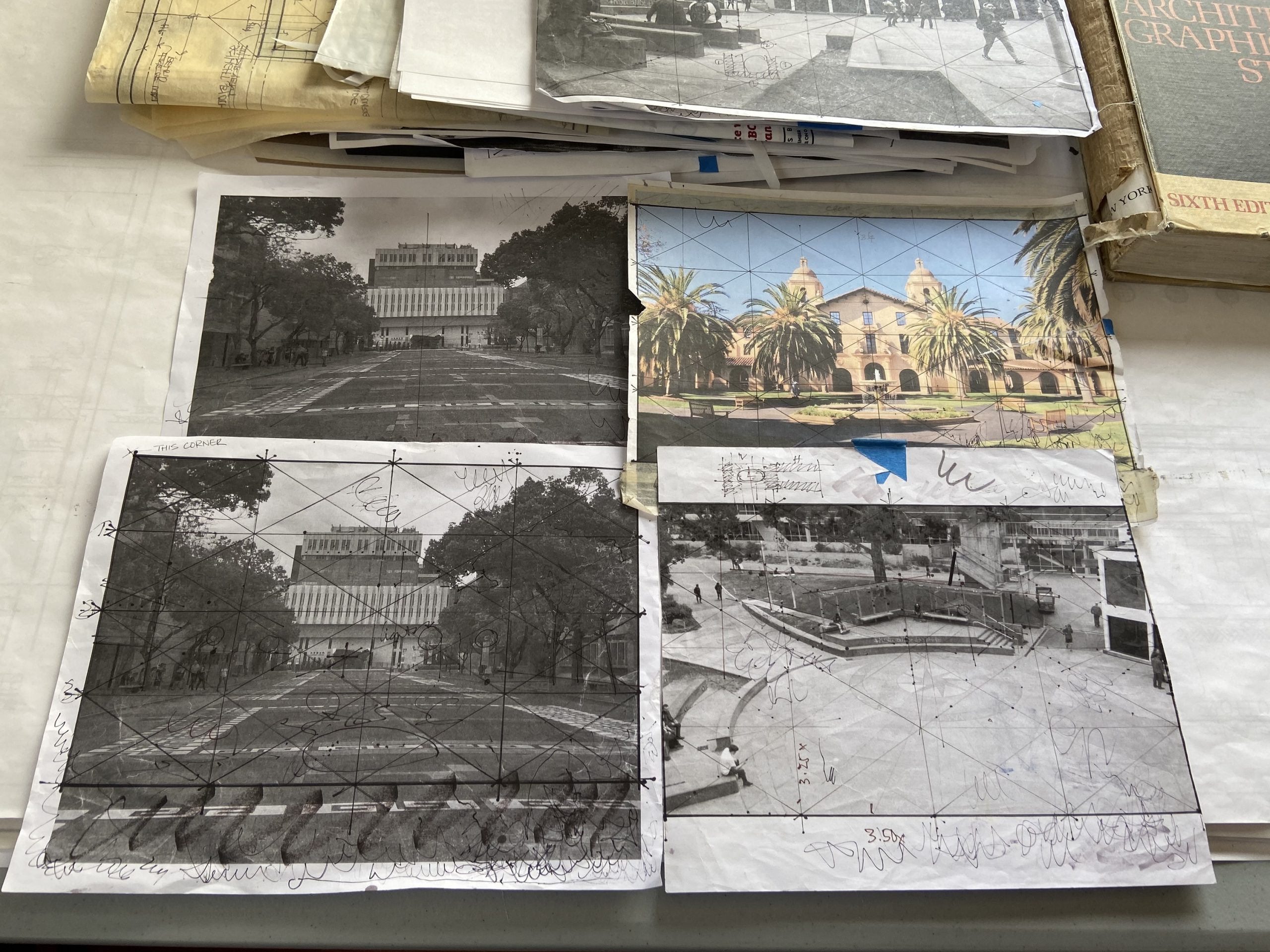

Inspired by the archival material within Contact Points, Reyes created the horizon toward which we move always recedes before us (figs. 3, 4), a series of hand-drawn architectural renderings of student organizing sites. They form an archive of Third World resistance movements based on the artist’s research and interviews with participants. Channeling the energizing affect of activism, they simultaneously acknowledge the receding horizon of activism’s effects: that no matter how much ground is gained, new challenges arise. The title of the series cites the concluding lines of a book by Asian American cultural critic Jeff Chang: “The horizon toward which we move always recedes before us. The revolution is never complete.”27 The invisible but suggested horizon lines seem interminably far away in these painstaking renderings of empty spaces, fringed by trees and flanked by imposing institutional façades.

Rendered in vellum, correction fluid, house paint, drafting inks, and painter’s tape—the stuff of architectural planning—the drawings capture the spatial scaffolding of transnational student organizing as it unfolded in the public sphere, both in iconic and obscure sites—from Palo Alto, California, to Hyderabad, India. The people who made these movements, however, are nowhere to be seen in these deactivated spaces. Reyes’s precise drawings emerge instead from those peoples’ constellated testimonies and memories: they document specific times of day, sightlines, composite imagery, and the tactical knowledge (contested locales, planned escape routes, and key congregation sites) required to stay safe. The architectural rendering—a form of visualizing a plan’s potential reality—imagines the incomplete project of these activist histories, a politics to come that seems precariously out of reach.

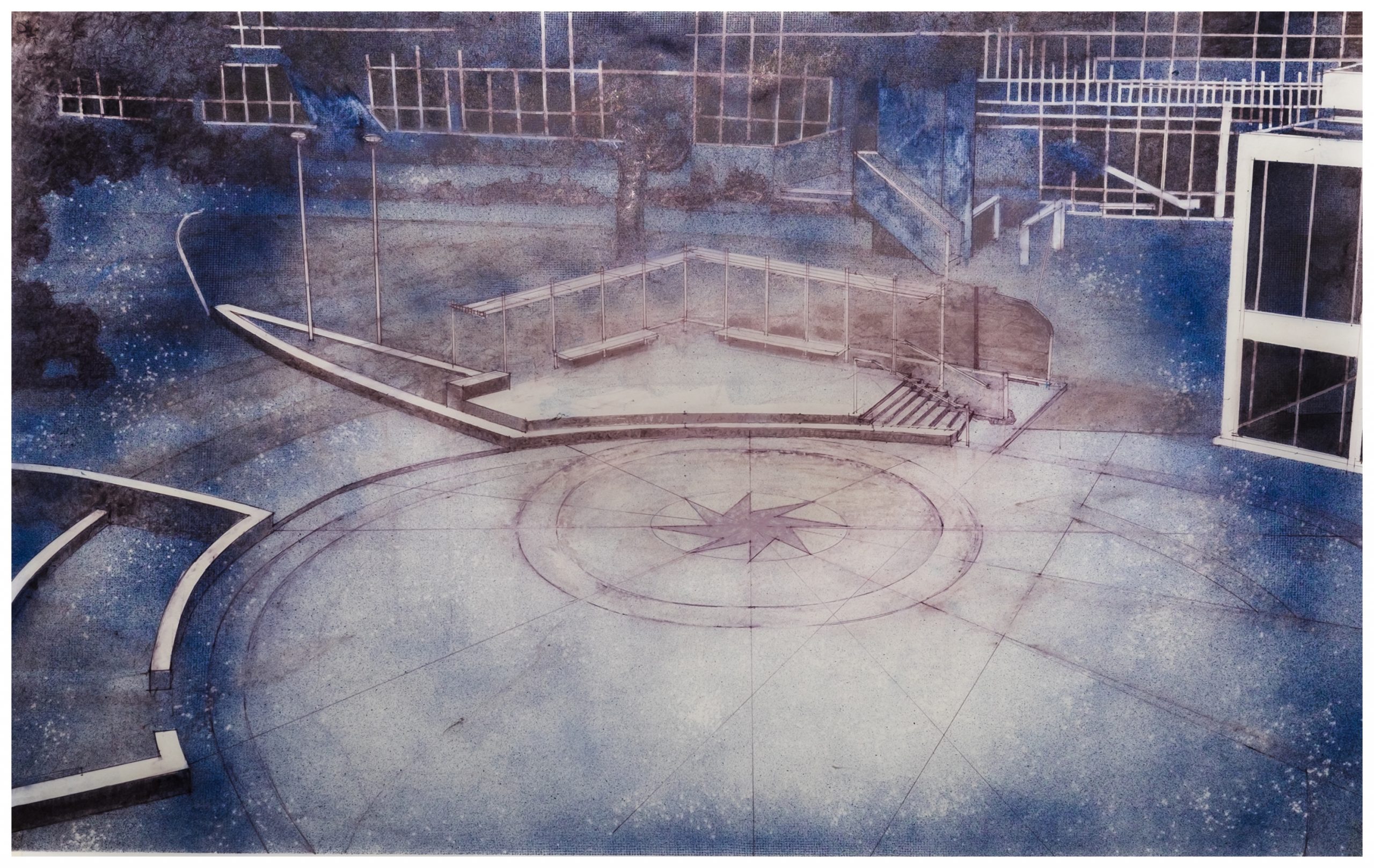

In the horizon toward which we move always recedes before us (San Francisco State Quad) (fig. 5), a bureaucratic grid of windows flanks a circular concrete plaza. Its identification—Malcolm X Plaza—is not inscribed, as it is now, on the perimeter of the sawtooth star that centers the plaza. There, in 1968, a coalition of students affiliated with the Black Students Union (BSU) and the TWLF initiated a strike against San Francisco State College in the midst of other demonstrations on campus against the Vietnam War. Gathering in front of the J. Paul Leonard Library, they demanded that the college offer a more equitable education that served, rather than sidelined, its working-class, nonwhite students, including admitting and employing more people of color and reforming curricula. The five-month long strike yielded administrative turmoil, police brutality, and the College’s partial consent to the students’ demands.28 A Black Studies Department was realized, as was the creation of a College of Ethnic Studies—the first such program in the country—but not one fully controlled by students. As protests rolled out on other campuses nationwide, hundreds of other higher education institutions across the country followed suit.29

The drawing’s vantage point did not exist in 1968; however, the exterior stairwell, catwalk, and dark windows in the right foreground represent elements of the Cesar Chavez Student Center, completed in 1975, whose design enabled easy surveillance of crowds below. Architecturally supporting the institution of campus policing, the perspective offers a good view for a sniper, reflecting the building’s design as “a place that facilitated student gathering but not student uprising.”30 In these luminous spaces of struggle, Reyes foregrounds the receding horizon of progress in haunting tones while documenting where and how alterity consolidated as power.

Maia Cruz Palileo

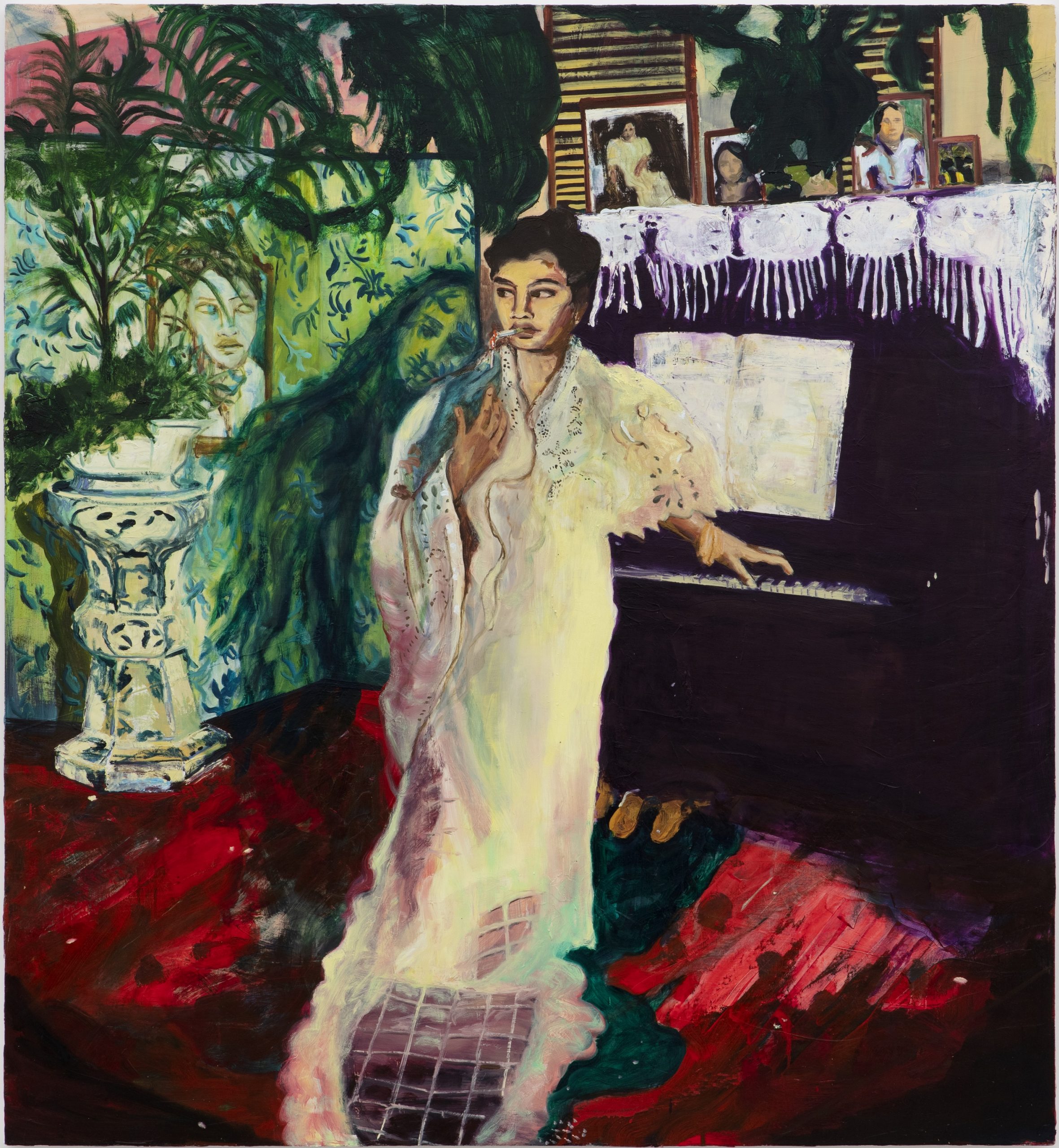

If the role of Filipino American activists in the social justice movements of the late 1960s presents one moment of racial formation, the project of US imperialism in the Philippines stands in very different relation to it. For painter Maia Cruz Palileo, the creative act is ancestral and thus cannot be separated from the subjection of the Philippines to US imperial rule and the anthropological study and educational reform that followed.31 In Palileo’s work, faces are inscrutable, but the lace embroidery is intricate, shadows become ghosts, water is everywhere, and colors bleed in tropical hues. The ground in these compositions is less an earthen platform than a threshold between here and out there, now and then, a surface whose porosity holds secrets and untold stories. The artworks’ liminality evokes the archipelago of more than 7,000 islands, in which the relationship between water and land, or figure and ground, is everywhere and always changing.

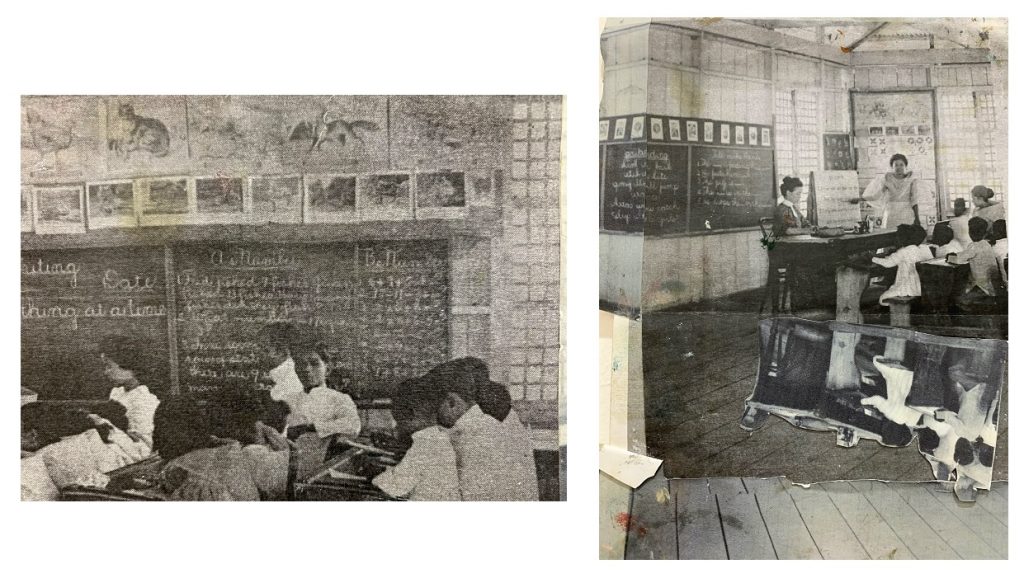

During a research fellowship at the Newberry Library in Chicago in 2017, Palileo encountered three key archives: a book of watercolor paintings by notable nineteenth-century Filipino painter Damián Domingo; the vast colonial photography archive of Dean Worcester (circa 1902); and Isabelo De los Reyes’s book El Folk-lore Filipino (1887).32

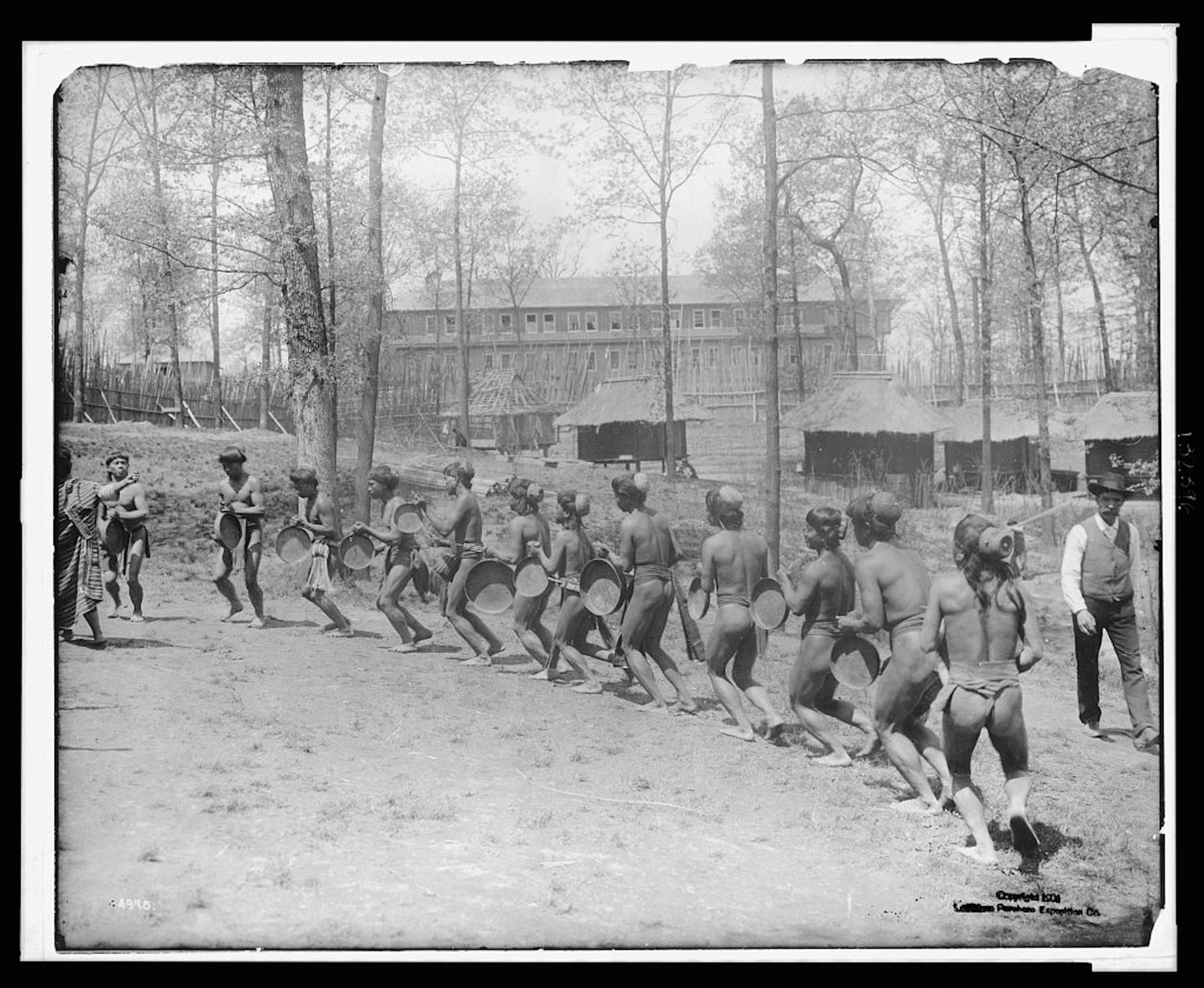

De Los Reyes (b. 1964) and Domingo (1796–1834) were affirmative foils to Palileo’s disturbing encounter with the Worcester archive. Worcester (1886–1924), a zoologist and US secretary of the interior who led the Benguet expeditions to the Philippines in 1902, sold his vast photographic archive to multiple institutions (fig. 6). Palileo was disturbed by these arresting images, initially feeling compelled to expose and recover the lost histories of educational and cultural violence that they effaced. Frustrating the empirical lens of colonial mastery, Palileo’s work confronts the viewer with incoherent narratives in which unidentifiable subjects occupy unidentified places, even nonplaces that can only ever register as fictions. While her paintings may activate what Bakirathi Mani defines as “diasporic mimesis”—a magnetism between the racialized subject represented and the racialized viewing subject’s identification with the image, often through the viewer’s conjuring of their own photographic memory archive—they equally deactivate the identificatory stability that ethnographic photography promises.33 More recently, she has sought alternatives to historical redress, creating worlds in the paintings that incorporate precolonial Indigenous spiritual beliefs in the Philippines, power structures that predated Spanish influence on religion, social norms, trade, and governance.

De los Reyes’s El Folk-lore Filipino introduced these ideas to a broad audience when it was published in 1887, received with intrigue and acclaim at the Exposición Filipina in Madrid that year. Then living in colonial Manila, and of Indio heritage, De los Reyes advanced a study of folklore that was of only recent interest to scholars and the public. It aimed to preserve customs and knowledges threatened by colonialism, centering the concept of what he termed el saber popular (in today’s terms, “local knowledge”)—not lore, but rather native understandings of medicine, geography, and agriculture.34 The book of Damián Domingo’s watercolor paintings that Palileo found illustrated the native dress of “Indios” and “Mestizos” from diverse social classes and professions in Manila and its surrounds. Domingo, who identified as a mestizo natural, or a mestizo native (in the Filipino context, a Chinese mestizo) held an inclusive view of racial hierarchy that reflected an inherently ambivalent position; the founding rules of the small private art academy that he ran in Tondo promised to accept applicants “of whatever class, whether Spanish, mestizo, or Indio” even as his work illustrated racial distinctions.35

Reflecting on these texts, Palileo recognized a disconnect in the homeland that her parents so fondly discussed and the history unfolding in the colonial archive. Driven by an earnest desire to recover lost heritage through the subjects photographed in the archives, she seeks a way to embody the pain of those subjects and to treat them with care and gentleness.36 In The Duet (fig. 7), the concept of the duet, an interdependent musical composition between two individuals, metaphorically resonates with the intertwining of a subject and their ancestry. A woman, dressed in white, languidly smokes while gazing toward her mirrored reflection at left, sensing but not seeing the womanly ghost that rests its head on her right shoulder. The woman’s left hand plays the piano while her right hand rests atop the ghost’s, an otherworldly duet that channels the creative spirit of the past in the production of the present. Framed photographs atop the piano furnish a familial audience. As in They Dreamed in English, there is a spatial ambiguity between indoors and outdoors; the richly carpeted parlor, flanked with foliage, may also be a courtyard, as suggested by a patch of blue sky and a vertical pink surface in the left corner, glimpsed through overhanging leaves. In this liminal space—enclosed but outdoors, where music exceeds the boundaries of private/public—the artist speaks to the threshold condition of feeling the presence of one’s ancestors most powerfully through the act of creation.

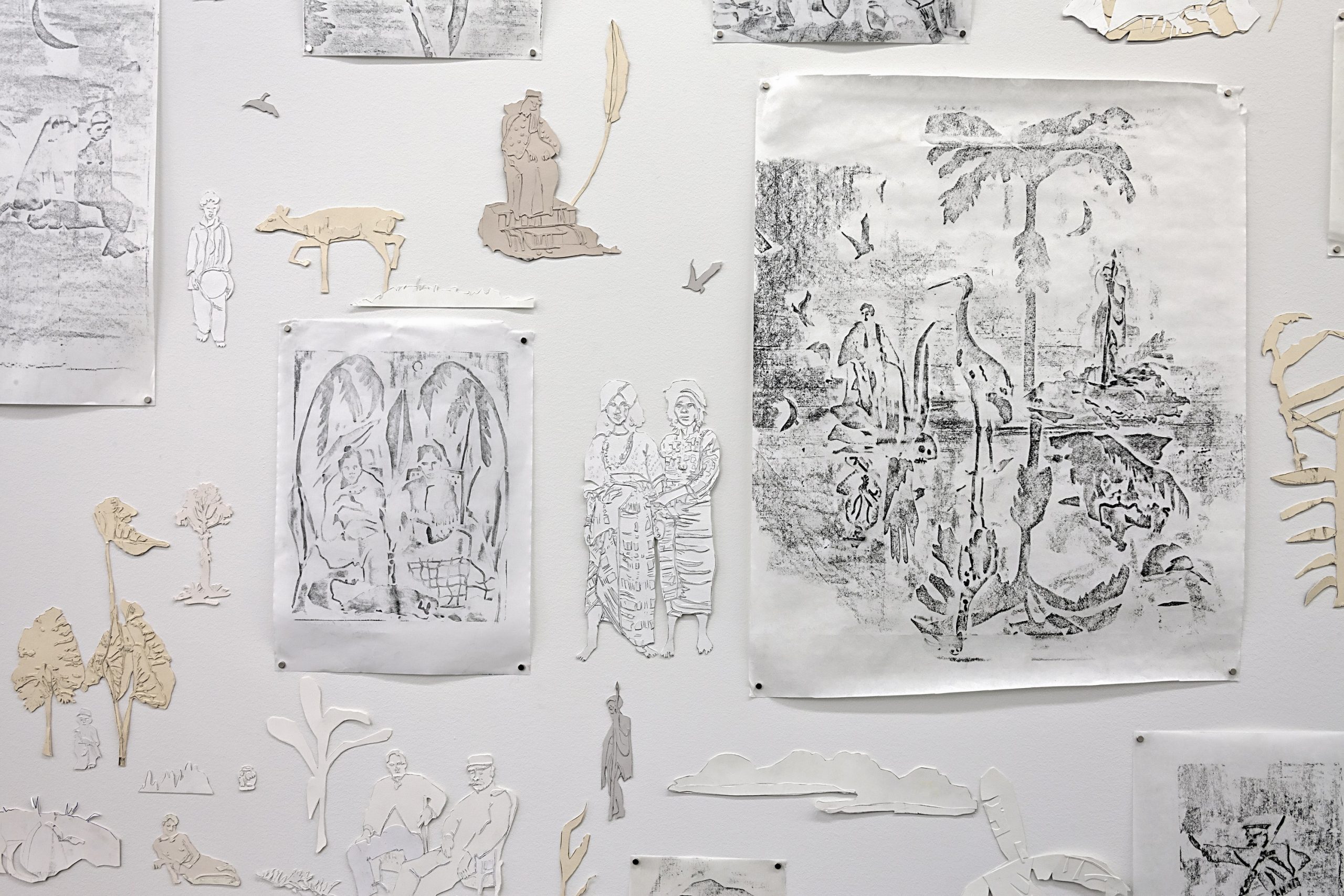

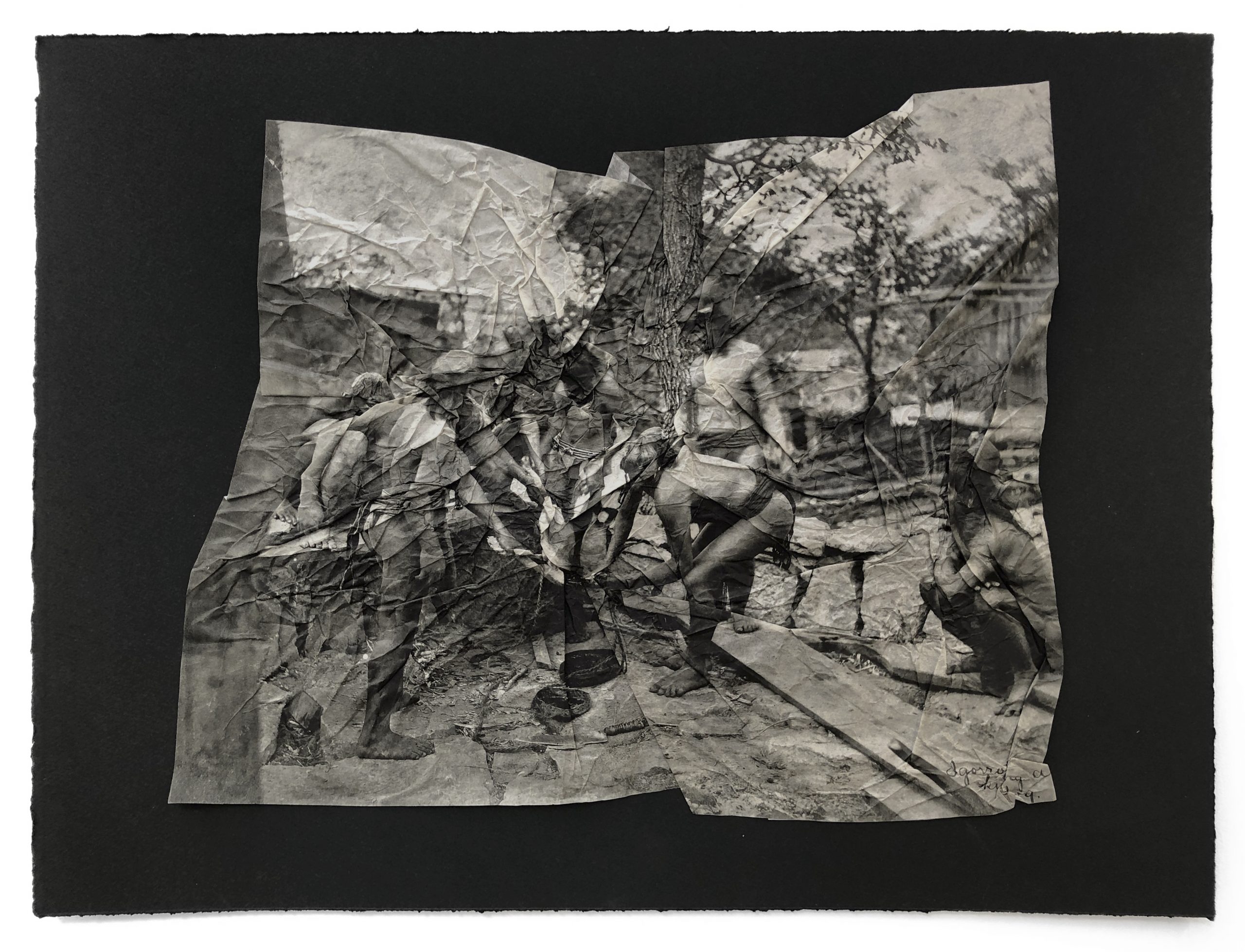

Photographs become found objects and points of departure; Palileo studies them, isolates a compelling element to sketch onto cardstock, and then cuts out that drawing. She then selects forms to comprise a graphic rubbing—recalling the ritual of making gravestone rubbings to memorialize the dead—as a collaged sketch for a painting (figs. 8–10). The painting takes form through layered remediations of photographic content, denaturing photography’s function of fixing subjects in place, time, and social and racial hierarchy, in what the artist describes as an improvisational “dance” with the painting’s composition.

Coalescence is a fantasy once or twice removed from the paintings and their displaced bodies—a metaphor for the Asian American diaspora. However rich in hues and secrets they are, the paintings also capture what Lauren DeLand describes as the “sinister dimension of image-making, suggesting effects of the probing, objectifying gaze of the colonial camera.”37 Palileo’s work understands the camera as an unseen voyeur in the colonial archive, whose documentary function supported the belief that culture was something that Filipinos were, not something they had.38 One can amend the historical narrative, but there is no recuperating the colonial subjects within it, no way to un-educate them from the foreign language and values imposed upon their reality and their dreams. In the watery, archipelagic land- and seascapes of her paintings, Palileo dredges the imaginary depths of family and colonial photographic archives to envision worlds that honor the hauntings of the Filipino colonial past—hijacking the colonial impulse to fix subjects in an evolutionary state, reorienting its evidence toward a project of speculative unfixing, and collaging its remnants into dreamlike futures.

⸹

These artists grasp the relationship between photographic history and colonial authority, which John Berger defined as “the division between those who organized and rationalized and surveyed, and those who were surveyed.”39 Photography was introduced to the Philippines during American colonial occupation to document the land and classify its resources, both material and human. As Coco Fusco argues, the photograph did not merely record the existence of racialized bodies; rather, “photography produced race as a visualizable fact.”40 This photographic logic coincided with the exhibition of live bodies: at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, one thousand Filipinos representing different ethnic groups were displayed at the fair’s Philippine Village (fig. 11).

We can understand Reyes’s and Palileo’s vexed relationships with the visual archive and the paradoxical identifier of “foreign in a domestic sense” as decolonial projects that reinscribe and dignify ways of living, thinking, and sensing that were violently devalued by colonial agendas and their legacies. Such practices and returns—whether historical, familial, or spiritual—articulate forms of “decolonial aesthesis,” a praxis invested not in multiculturalism but in interculturality, which “promotes transnational identities-in-politics.”41

Acknowledging decolonization as a matter of redistribution, I turn to Hong-An Truong’s definition of a decolonial project: “An interrogation of subjectivity and formal strategies born of the violence of colonialism—exploding and miming back what is encoding the archive, probing the narratives, told through visual culture, about . . . histories of Asia broadly—and delinking from colonial imagery while engendering non-imperial subject(ivities).”42 Many artists of Filipino descent enlist tools of colonial history—the apparatus of photography, the archive, the ethnographic aesthetic—to leverage and subvert its ambivalence. Stephanie Syjuco (b. 1974), for example, links consumerism, labor, and colonialism through “cultural forensics.”43 In the series Headshots (2021), Syjuco rephotographs materials from national archives and manipulates that imagery through pixilation; in Afterimages (fig. 12) she subjects photographs of the Philippine Villagers to the material violence of crumpling and folding. Both projects undo the clarity of the photographic message that subtends its historical value and authority, revealing the archive as a violent and flawed construction. In her large-format photographs, Gina Osterloh (b. 1973) creates staged photographic tableaux—a compositional technique used both in the national history museum and in anthropological photography of colonial encounter —that engage camouflage as a contradictory assertion of visual presence and metaphorically invoke the assimilationist impossibilities of “blending in” as an Asian American. New archives have emerged, too, such as Wendy’s Subway in Brooklyn, or PJ Gubartina Policarpio and Emmy Catedral’s nomadic Pilipinx Library.

Asian American culture emerges from American ambivalence. The tensions between the conceptual alienness and social embeddedness of the Asian American presents “an alternative site,” writes Lowe, “where the palimpsest of lost memories is reinvented, histories are fractured and retraced, and the unlike varieties of silence emerge into articulacy.”44 The histories that Reyes sustains have never felt more precarious, given recent crackdowns on democratic movements in Asia and calls to ban the teaching of critical race theory in schools and universities. Palileo’s project illuminates the whitewashing of American colonial history with renewed visions of its cultural margins. Bringing forth the agency of Filipino diasporic subjects in histories of colonial suppression and survival, anti-racist coalition politics, and surveillance, they offer a transformative rather than additive presence to American art. Their telescopic perspectives embed the decolonial imperative problematically within the present, surfacing the ideology of the archive in order to estrange the spaces and sites of knowledge it builds. Illuminating the operant ambivalence with which the Filipino subject is identified, their work re-articulates what Asian America was in its moments of emergence and what it could become if we reenvisioned American history as a site of global reckoning with the worlds made through and by its ambivalent feelings.

Cite this article: Ellen Yoshi Tani, “Un-Disciplining the Archive: Jerome Reyes and Maia Cruz Palileo,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11606.

PDF: Tani, Un-Disciplining the Archive

Notes

- Renato Constantino, “The Miseducation of the Filipino,” in Vestiges of War: The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream, 1899–1999, ed. Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia (New York: NYU Press, 2002), 178. Originally published as “The Mis-Education of the Filipino,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 1, no. 1 (Autumn 1970), 20–36. Constantino’s article title references Carter G. Woodson’s iconic 1933 book, The Mis-Education of the Negro, in which he argued that black children were being culturally indoctrinated to believe their inferiority and to accept racial segregation as just. Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1933). ↵

- While I recognize that the term “Filipino” naturalizes the colonial position, I use it throughout for the sake of nomenclature. See Nathan Gilbert Quimpo, “Colonial Name, Colonial Mentality and Ethnocentrism,” Public Policy 4, no. 1 (January 2000): 1–49. ↵

- Emphasis original. Homi Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse,” in “Discipleship: A Special Issue on Psychoanalysis,” special issue, October 24 (Spring 1984): 126. ↵

- Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 8. See also Sarita See, The Decolonized Eye: Filipino American Art and Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009). ↵

- Oxford English Dictionary, online edition, s.v. “ambivalence,” accessed April 28, 2021, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/6176?redirectedFrom=ambivalence. ↵

- Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 4. ↵

- Lowe here describes the unique identity of post-1965 Asian immigrants (those who arrived after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act), most of whom came from societies disrupted by colonialism, neocolonial capitalism, and war (primarily South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands). Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 16–17. ↵

- See Colleen Lye, “Introduction: In Dialogue with Asian American Studies,” Representations 99, no. 1 (Summer 2007): 1–12; and Anne Anlin Cheng, Ornamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). Cheng’s book does important theoretical work in this regard, but in its focus on East Asian feminization and racialization does not account for the primitivizing representation of South Pacific Islanders (specifically, those subject to Western colonization). ↵

- Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2014), 109. ↵

- See Copeland et al. “A Questionnaire on Decolonization” in October 174 (October 2020): 3–125; and Adam Hochschild, “The Fight to Decolonize the Museum,” The Atlantic, January/February 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/01/when-museums-have-ugly-pasts/603133. See also Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museum: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution (London: Pluto Press, 2020). ↵

- Christopher Green, “Beyond Inclusion,” Art in America, February 1, 2019, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/beyond-inclusion-63604; Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. ↵

- “I feel the battle I face . . . as artist and critic is the same as it ever was: to have black genius accepted without condescension.” Judith Wilson, Lorraine O’Grady: Critical Interventions (New York: INTAR gallery, 1991), n.p. ↵

- This contemporary turn away from the continental reflects an understanding of the archipelago—a cluster of islands—as a more suitable geographic and analytical framework for American studies. See Archipelagic American Studies, ed. Brian Russell Roberts and Michelle Ann Stephens (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). ↵

- Omi and Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, 13. ↵

- Camara Dia Holloway, “Critical Race Art History,” Art Journal 75, no. 1 (2016): 89–92. ↵

- See Jacqueline Francis, Making Race: Modernism and “Racial Art” in America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011); ShiPu Wang, The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa (Pittsburgh: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); Linda Kim, Race Experts: Sculpture, Anthropology, and the American Public in Malvina Hoffman’s Races of Mankind (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018); Jennifer A. González, Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008); Maurice Berger, White Lies: Race and the Myths of Whiteness (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999); “Positions: Race and Ethnicity in an Expanded American Art History,” American Art 31, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 77–81; and the anthologies Saturation: Race, Art, and the Culture of Value, ed. C. Riley Snorton and Hentyle Yapp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020) and Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History, ed. Kymberly Pinder (New York: Routledge, 2002). ↵

- Susette Min, Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 3. ↵

- Min, Unnamable, 15; see also Min, “Refusing the Call for Recognition,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10960. ↵

- Min, Unnamable, 1–32. ↵

- Here, and as I have written elsewhere with regard to Black cultural practice, I align with scholars Sampada Aranke, Huey Copeland, Adrienne Edwards, and Darby English in understanding opacity, withdrawal, and abstraction as conceptual tactics mobilized by artists of color for whom visibility is a fraught register. ↵

- See, Decolonized Eye, xi-xiii. ↵

- The I-Hotel, which opened in 1854, was a low-income, single-occupancy, residential hotel from 1968 to 1977, whose storefront spaces housed progressive community organizations, bookstores, and art and music venues. See Karen Tei Yamashita, I Hotel, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2019). ↵

- This exhibition is discussed at length in Ellen Tani, “Spectral Frameworks: Jerome Reyes’ Passages of Affect” in Scramble: Stanford MFA (Stanford, CA: Department of Art and Art History, 2011), n.p., and in Thea Quiray Tagle, “After the I-Hotel: Material, Cultural, and Affective Geographies of San Francisco” (PhD diss., University of California San Diego, 2015). ↵

- See Estella Habal, San Francisco’s International Hotel: Mobilizing the Filipino American Community in the Anti-Eviction Movement (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007). ↵

- Project statement on artist’s website, accessed April 23, 2021, http://jeromereyes.net/projects/contact-points. See also Jerome Reyes and tammy ko Robinson, “No matter where we move we look at the same moon,” Public Space/Contested Space Imagination and Occupation (New York: Routledge, 2021), 144. ↵

- PJ Gubatina Policarpio and Jerome Reyes, “Reading at the Edge of the World: The Horizon Toward Which We Move (Part II),” Art 21, October 9, 2019, https://art21.org/read/reading-at-the-edge-of-the-world-part-ii. ↵

- Chang, We Gon’ Be Alright: Notes on Race and Resegregation (London: Picador, 2016), 196. ↵

- “50th Anniversary of the SF State Student Strike,” KQED News, 3:39 minutes, posted February 25, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=As_P3DueKrY&t=2s. ↵

- Gary Okihiro frames the establishment of Ethnic Studies as more concession than victory: the TWLF demanded a Third World curriculum but instead got Ethnic Studies, which spurred its institutionalization across US campuses and, he argues, intellectual segregation. Gary Okihiro, Third World Studies: Theorizing Liberation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). Daniel Phil Gonzalez, student activist and one of the first professors appointed to helm Asian American Studies at San Francisco State, corroborates this analysis in a 2018 interview: Emil Guillermo, “Asian-American Scholars Honor SFSU’s Pioneering Ethnic Studies,” Diverse Issues In Higher Education, April 2, 2018, https://diverseeducation.com/article/113609. ↵

- This description was offered by the building’s architect, Paffard Keatinge-Clay, quoted in “Construction of the Cesar Chavez Student Center,” 1974, Academic Technology Archive, San Francisco State University, item TP-ATA-024, https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/ata/bundles/238880. ↵

- Scientific conquest predated the military conquest of the Philippines, yielding a vast archive of artifacts and photographs that formed the core collection of the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History. See Sarita See, Filipino Primitive: Accumulation and Resistance in the American Museum (New York: New York University Press, 2017). ↵

- Carlos Quirino, “Damian Domingo, Filipino Painter,” Philippine Studies 9, no. 1 (January 1961): 78–96. ↵

- Bakirathi Mani, Unseeing Empire: Photography, Representation, South Asian America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 5. ↵

- Benedict Anderson, “The Rooster’s Egg: Isabel de los Reyes and El folk-lore filipino.” Verso books blog, June 15, 2016, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2705-the-rooster-s-egg-isabelo-de-los-reyes-and-el-folk-lore-filipino. ↵

- Quoted in Luciano P. R. Santiago, “At the end of the rainbow: the last will and testament of Damian Domingo,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 28, no. 1 (March 2000), 82. ↵

- Maia Cruz Palileo, interview with the author, December 12, 2020. ↵

- Lauren DeLand, “Maia Cruz Palileo,” Art in America, May 1, 2019), https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/maia-cruz-palileo-62676. ↵

- See, Filipino Primitive. ↵

- Emphasis original. Jonathan Berger, Understanding a Photograph (New York: Aperture, 2013), 70. ↵

- Coco Fusco, “Racial Time, Racial Marks, Racial Metaphors” in Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self, ed. Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis (New York: International Center of Photography; New York: Harry N, Abrams, 2003), 1. ↵

- Emphasis original. Rolando Vasquez and Walter Mignolo, “Decolonial Aesthesis: Colonial Wounds/Colonial Healings” from the project Decolonial AestheSis, Social Text: Periscope, July 5, 2013, https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings. ↵

- hong an truong, Nayoung Aimee Kwon, and Guo-Juin Hong, “What/Where is ‘Decolonial Asia’?” from Decolonial AestheSis, July 15, 2013, https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/whatwhere-is-decolonial-asia. ↵

- Catherine Clark Gallery, Stephanie Syjuco: Native Resolution (San Francisco: Catharine Clark Gallery, 2021), https://issuu.com/cclarkgallery/docs/syjuco_native_resolution_available_2021_issuu. ↵

- Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 6. ↵

About the Author(s): Ellen Yoshi Tani is A.W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts