Asserting Agency: Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Scrapbook

PDF: Schneider, Asserting Agency

Wrapped in frayed and torn brown burlap, the scrapbook of the pioneering African American sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877–1968) outlived a disastrous warehouse fire in Philadelphia in 1910, which destroyed all her sculpture, representing sixteen years of work, from her time as a student at the School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) in Philadelphia to her three-year stay in Paris (fig. 1).1 The loss included sculptures shown at prestigious exhibitions held while she was in dialogue with Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), who admired her work. Fuller would later create many major sculptures whose cultural themes shaped the direction of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Emancipation (1913; Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists and the Museum of African American History/MAAH), Mary Turner: A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence (1919; MAAH), Ethiopia Awakening (1921; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture), and Talking Skull (1937; MAAH). She would also go on to mentor several important female artists, including Augusta Savage and Loïs Mailou Jones. Few records survive that document her early works or her accomplishments abroad. However, a recent rediscovery of a personal scrapbook documenting the early years of this important sculptor provides an opportunity to reconstruct some of what has been lost. The scrapbook also demonstrates the enduring impact of Fuller’s time in France on her career and on the career trajectories of other Black visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance, a period of profound cultural creativity centered in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s.2 The collection expands Fuller’s voice in the archival record and reveals her active interventions in transnational art practice and in crafting the critical reception of her work.

At the end of one of the most restrictive lockdown periods during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was difficult to conduct any research involving travel, the Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University, home to the largest collection of Fuller’s work and ephemera, received the artist’s personal album, which Fuller used from 1899 into the 1930s. Velma J. Hoover, a close friend and early biographer of the sculptor, had preserved the scrapbook for safekeeping in North Carolina. Hoover’s daughter Carnel found it when she was moving. Although Fuller’s son Solomon Fuller Jr. presumed that researcher Sylvia Dannett had the scrapbook, Fuller must have given it to Hoover sometime after 1964. Solomon Fuller Jr.’s ardent pursuit of the lost scrapbook, evident in letters to Dannett and the publisher, indicates its value and importance to her family.3 With photographs, news clippings, and catalogues from the beginnings of her more than seventy-year career, the collection documents Fuller’s artistic and critical communities during her stay in Paris, while handwritten marginalia in the scrapbook reveal ways in which she negotiated race, recording “unwritten histories.”4 As much as I longed to travel to French and American archives to pursue my research on Fuller, here was a treasure trove just a few miles from my home.

Building on Renée Ater’s groundbreaking 2011 study of Fuller, as well as the work of several other scholars, my project focuses on Fuller’s early pieces and related work at the Danforth Art Museum, considering how the artist and the museum staged her studio and work.5 Most scholars have focused on Fuller’s later extant works and engagement with political debates concerning race, national identity, and culture in the United States. When researchers discuss her early works, they regard them as evidence of her nascent interest in images of struggle now manifest in depictions of African Americans or as derivative of her association with Rodin. At a time when there is renewed attention to Fuller’s work, the information in the scrapbook indicates that the importance of her transnational art practice was already present in her career.6

While in the early twentieth century Fuller was seen by Black art critics as a foundational figure for Black art in the United States, she has subsequently become best known alongside colleagues of a later generation, as part of the Harlem Renaissance. However, the ten-year gap in her career caused by marriage, motherhood, and fire makes the connection less linear. As a conduit for French influences, Fuller’s sculptures compel us to reconsider her international legacy and its influence on a subsequent generation, complicating a singular categorization for her work.7 Rooted in her academic training in Philadelphia and Paris, Fuller employed a naturalistic style, albeit one that blended emotional and imaginative interpretation. Her art demonstrates not only how the fin de siècle avant-garde continued to inform her work but also how she transcended art-historical categories that limit our understanding of the nuances of her shifting styles during her decades-long career. While there is no one style associated with the Harlem Renaissance, the figurative tradition dominates, a mode that is informed by Fuller’s practice.8 In the context of increased national and international interest in Fuller, her work, and Black experiences in a racialized society, the discovery of Fuller’s scrapbook animates archival remnants of the sculptor’s career foundations by providing an opportunity to see how she intentionally staged her career, wrote her own history in the pages of the album, and provided a role model for subsequent artists, like Edmonia Lewis and Henry Ossawa Tanner had done before and alongside her.9

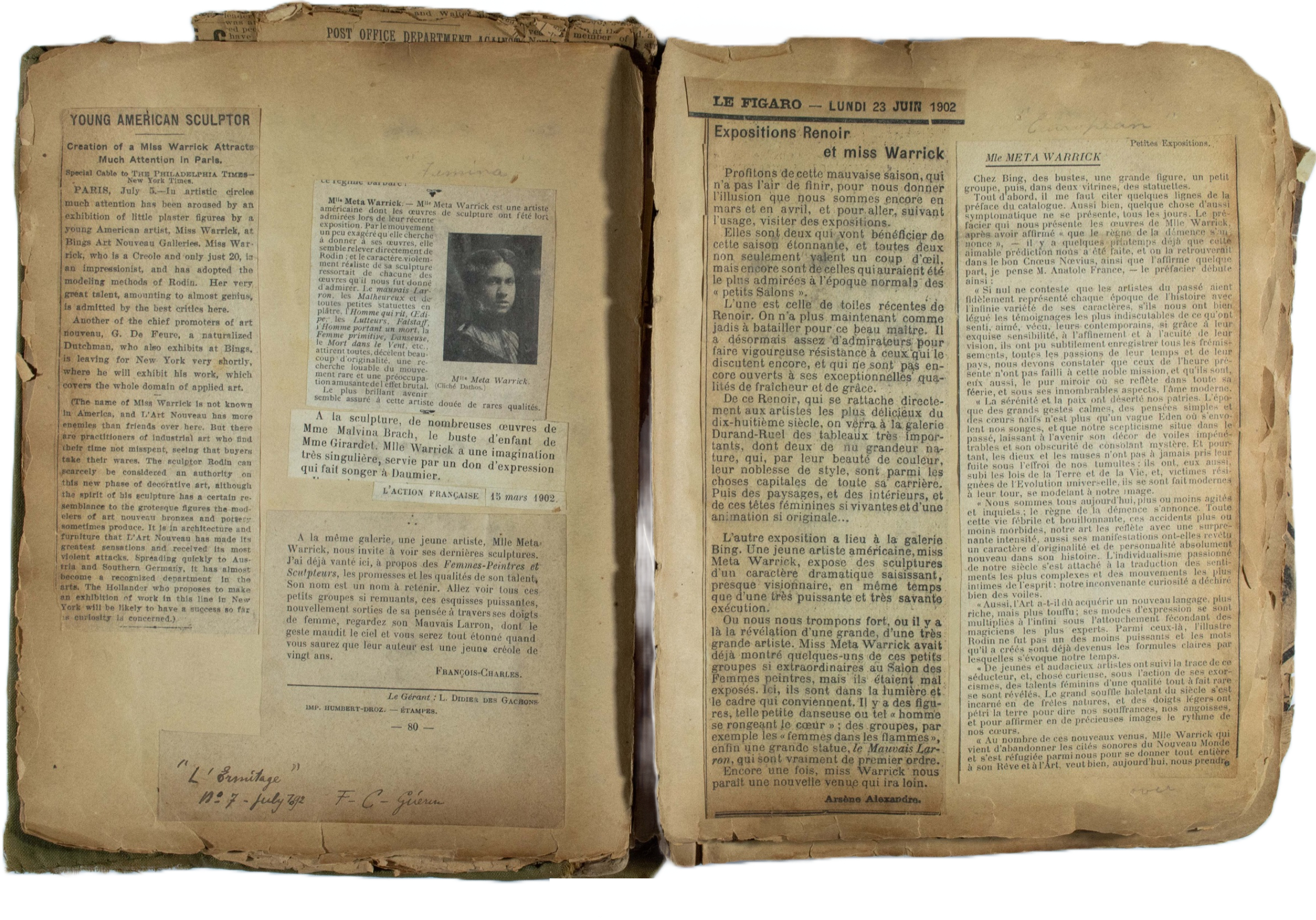

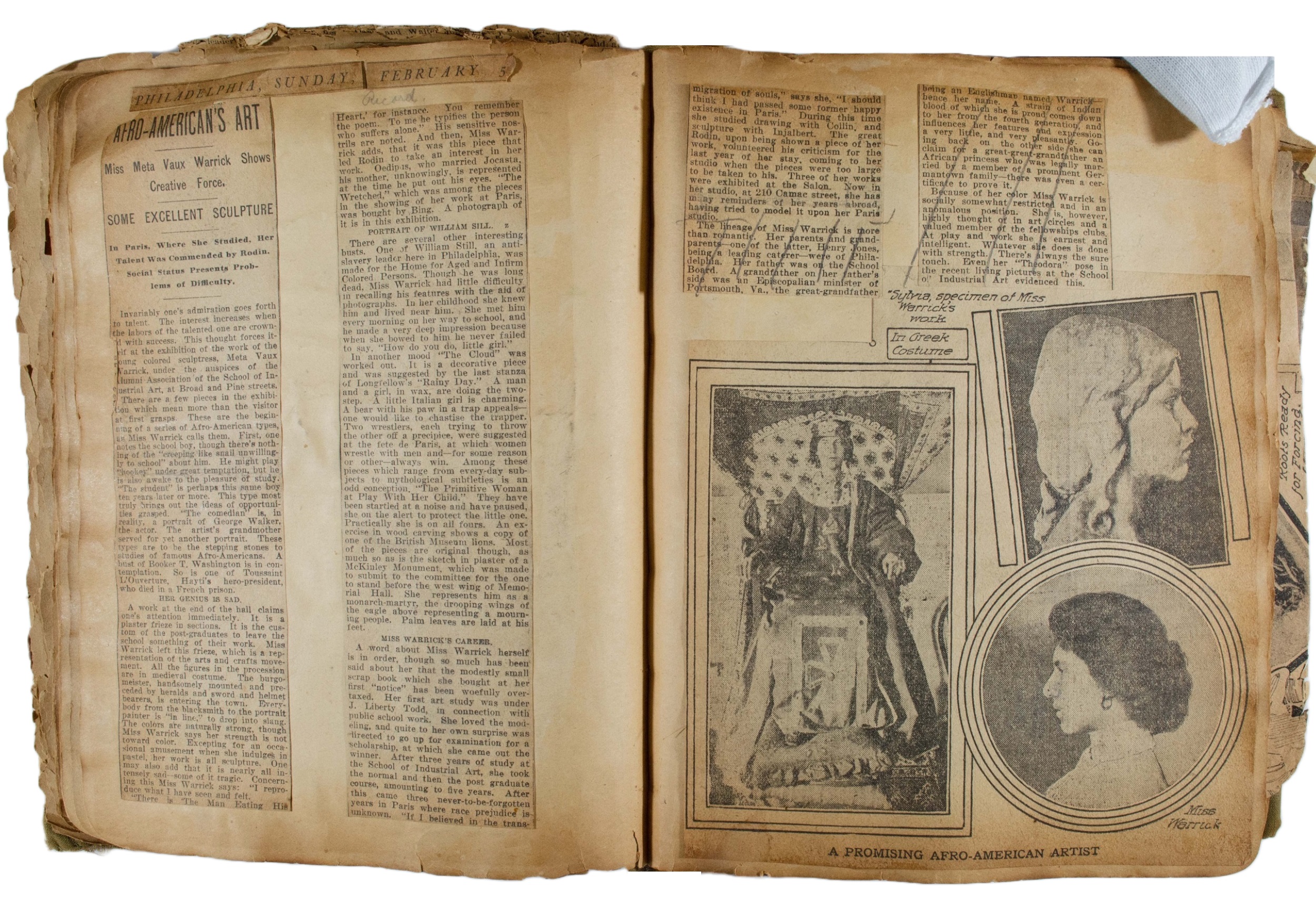

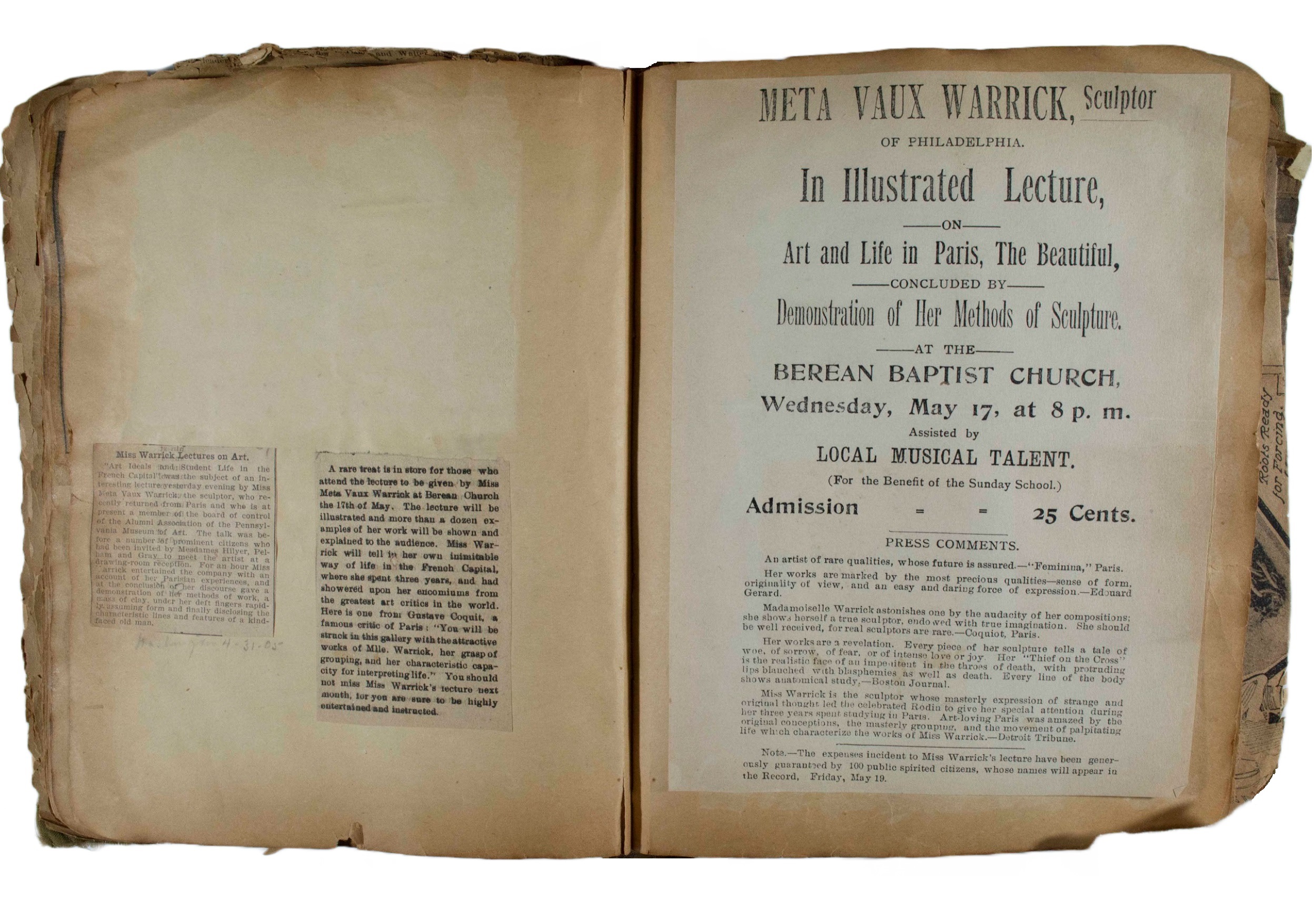

Fuller’s endeavors parallel contemporary efforts in African American communities to create a narrative by writing in books, periodicals, journals, diaries, and scrapbooks.10 Often juxtaposing stereotypical articles in the white press with more sensitive stories of the African American experience, scrapbookers routinely challenged the racist narrative as well as provided an alternative history in danger of being forgotten. Scrapbooks constitute an instructive link from the past to future generations. For example, in the 1899 preface to The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, W. E. B. Du Bois, one of Fuller’s early champions and a lifelong friend, acknowledged the value of William Dorsey’s collection of more than four hundred scrapbooks for his research.11 By pasting each review and mention into her scrapbook, Fuller documented her roots and associations in the art world, and she used the book to amplify her lived experiences when giving lectures, providing information to future biographers. At the beginning of her record keeping in Paris, she preserved review articles with few pencil notations other than the journal’s name and date, as in the two-page spread with six separate reviews of her work in two different exhibitions in both English and French (fig. 2). When she returned to the United States, she began to make more fulsome commentary, integrating letters and photographs to create a more complete history, as seen in the pages that show her edits to a 1905 article (fig. 3).12 After speaking at the Berean Baptist Church in Washington, DC, in the same year, she inserted the notice advertising the event into the scrapbook, including several quotations from French and US critics attesting to her skills and accomplishments (fig. 4). At public events throughout her life, Fuller brought along supplemental material, from slides and sculptures to wet clay for demonstrations, so it is likely the scrapbook also accompanied her, allowing her to add evidence of her long-standing career and recognition.

In 1938, Gammon Theological Seminary Professor Frank W. Clelland thanked Fuller for loaning him the scrapbook. He wrote:

The scrapbook which I spent a good part of yesterday reading fascinates me very much coming as it has after all my other reading about your work. I am able to recreate by my imagination and sympathetic understanding much of the personality which lies back of the events and experiences there recorded.13

His comments underline the intimate nature of the keepsake, which Fuller shared only with trusted individuals to build her biography, much in the way that Dorsey created his scrapbooks to record and share Black achievements.14 Fuller’s scrapbook is thus both personal and professional, an active tool that constructed and shared her personal and professional story. As late as 1964, Dannett referred to the scrapbook alongside a personal interview in composing her entry on Fuller in the 1966 Profiles of Negro Womanhood, which she dedicated to Fuller.15

Full of fragile treasures poised to excite any archivist, the worn and well-handled scrapbook opens at least three avenues for further exploration: Fuller’s extensive public recognition in Paris; her early sculptural accomplishments, indicative of her iconographic and stylistic intentions; and her resistance to racialized biography by white US critics. Like many African American artists, Fuller wanted recognition for her art without consideration of her race.16 By her later career, she asserted her identity as a Black woman through her choice of topics. In France, she received accolades, but on her return to the United States in 1902, she was ignored by the white art market while being praised by the African American press and receiving commissions from the African American community. For example, the French press loved her piece Man Eating His Heart (Secret Sorrow) (c. 1900; destroyed) for its suggestive narrative, while the American press did not even mention the work’s literary reference.17 As an African American woman, Fuller faced many limitations in the art world. Her album demonstrates how she documented her career to establish her contributions to the history of art and to authenticate her artistic legitimacy by her own agency. Through cutting, pasting, and annotating, she asserted her identity and pushed back against these restrictions. By writing in the margins, she heralded her achievements and contested racialized reception to ensure she would not be marginalized.

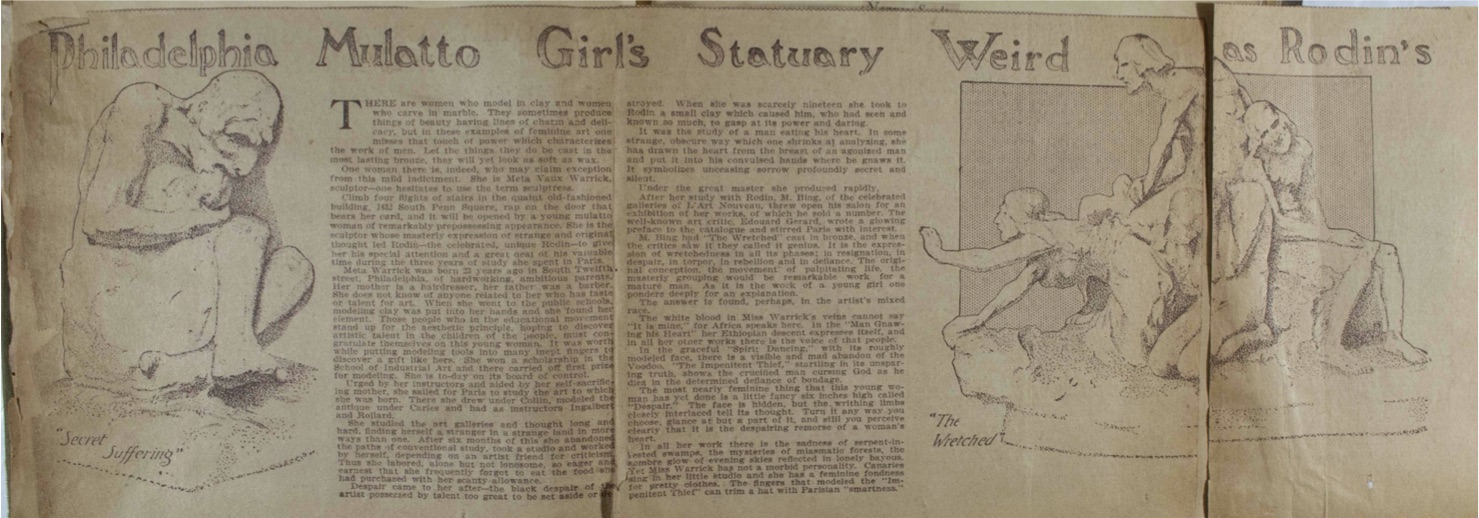

The information gleaned from the scrapbook underlines her intention to blend her European training with her role as an American sculptor of the Black experience. In Paris and the United States, contemporary critics were quick to notice the similarities between Rodin’s and Fuller’s sculpture in subject and execution. Many of her early works, such as Man Eating His Heart and The Wretched (1902; Maryhill Museum of Art), have morbid subject matter and an unfinished quality meant to evoke strong emotional responses (fig. 5). Figures writhe and struggle in uncomfortable positions, often inflicting bodily self-harm. Her subject matter draws from literary, mythological, and biblical tragedies. She based Man Eating His Heart on Stephen Crane’s poem “In the Desert,” while The Wretched references Rodin’s Gates of Hell (1880–1917), with an anguished thinker included among the miserable.18 Called the “The Delicate Sculptor of Horrors” in the French press, she most likely would have continued the “horrors” had she found patronage back in the United States after her return to Philadelphia in 1903.19 Without a market for these themes, she was encouraged by Du Bois to turn to representing African American experiences and domestic scenes. Although these subjects are significant, Fuller craved the freedom to create sculptures that responded to the modern art she observed in Paris.

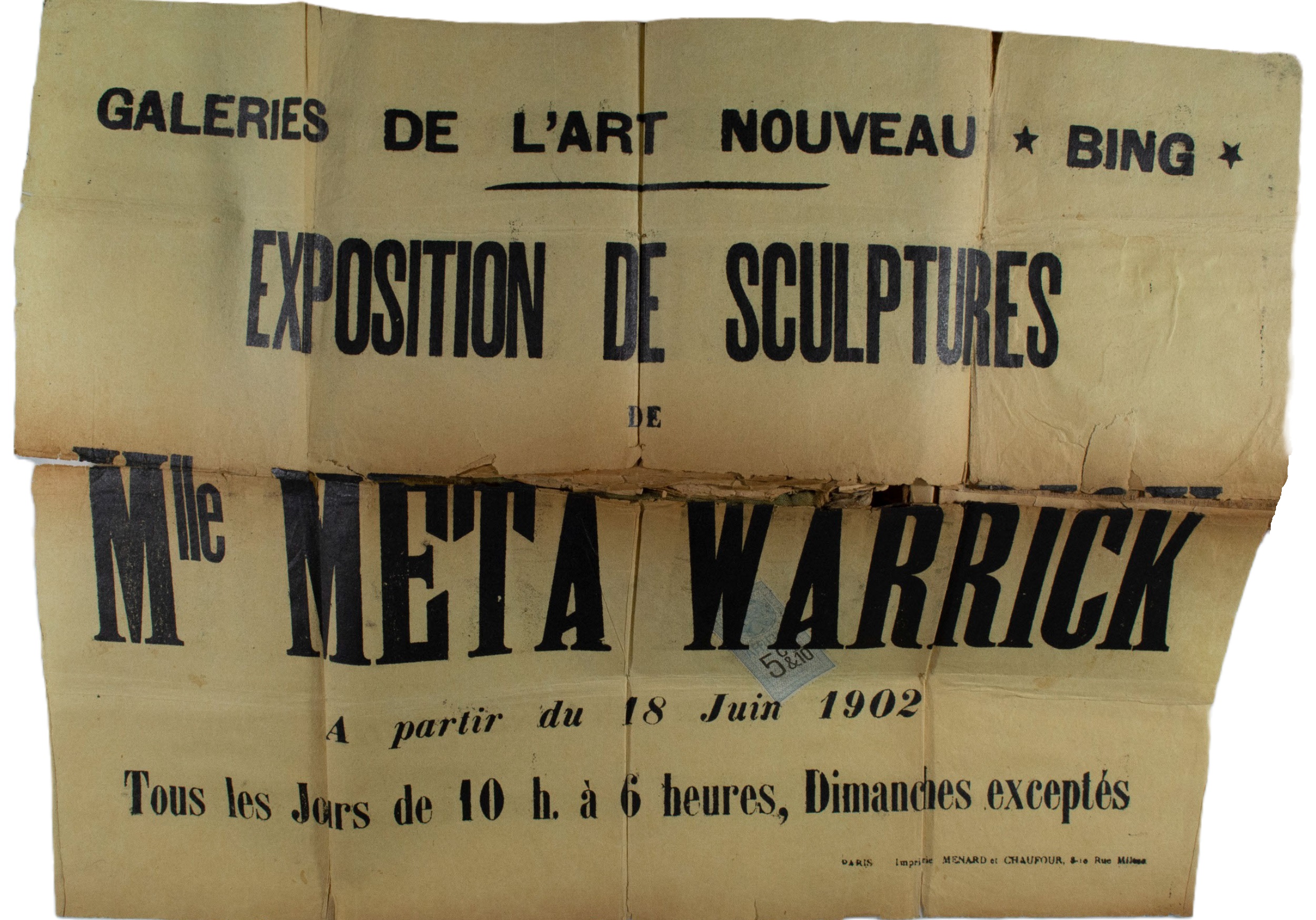

Several items in the scrapbook album crystallize our understanding of her first solo exhibition in June 1902 at the celebrated Samuel Bing Gallery of Art Nouveau in Paris, a distinction that attests to the esteem in which she was held by her European contemporaries. Following shows of Post-Impressionist Marie Bermond’s paintings in March 1902 and Neo-Impressionist Paul Signac’s oils, pastels, and watercolors in June 1902, Fuller’s exhibition demonstrated Bing’s commitment to established as well as unknown artists, particularly women.20 Although scholars have long known there was a catalogue to the show, there was no known extant copy of the publication until the scrapbook acquisition.21 In the introductory essay, Edouard Gérard praises Fuller’s work for its “sense of form, originality of view, and an easy and daring force of expression.”22 This manuscript contains Fuller’s own pencil marks for the works she sold at the exhibition, documenting her accomplishments in the catalogue like a gallery ledger book. In addition, Fuller preserved related materials demonstrating the extensive advertising efforts that accompanied the momentous exhibition of twenty-two sculptures. The largest is a fragile poster, folded several times on thin paper, most likely mailed, showing that audiences were reached in multiple ways (fig. 6).23

Subsequent related notices collected by Fuller in the scrapbook indicate that many saw or at least read about the exhibition at Art Nouveau. The esteemed critic Arsène Alexandre praised the sculptor’s work in Le Figaro: “A young American artist, Miss Meta Warrick, exhibits sculptures of a strikingly dramatic, almost visionary character, at the same time as a very powerful and very skillful execution.”24 After citing specific pieces such as Man Eating His Heart, Woman in Flames (possibly Wildfire), and The Impenitent Thief, he concluded that Warrick would go far in her career.

Another critique in Le Fronde concurred that the young woman had great talent, writing: “She is barely twenty years old; and the works are already more than promising. Yet they amaze with the rarest qualities.” Having erroneously subtracted a few years from her age so that she seemed more of an ingenue, he wrote a detailed account that praised her training while crediting her with independence from orthodox convention. He continued, “It also requires boldness, to dare to express oneself freely, and not make concessions to conventional ways of seeing and feeling. No academic dogma weighs on the young artist. She meditates, she dreams, she works without being intimidated by the tyranny of formulas.”25 He believed her art transcended predictable academic styles, a sentiment Fuller promoted throughout her career as well.

Even the writers in the newly founded magazine Femina, who had admired the sculptures but decried Fuller’s lack of femininity in an earlier exhibition, unilaterally lavished praise on her work in 1902, identifying “a commendable pursuit of rare movement and an amusing preoccupation with brutal effect. The brightest future seems assured to this artist endowed with rare qualities.”26 In addition to citing ten specific works, the article was supplemented by a photograph of Fuller in a high-collared, diaphanous V-neck black dress, giving readers a chance to see the artist without mentioning race explicitly, as every US writer did.

A 1903 letter from Bing on dramatically florid letterhead documented the continued contact between the gallery owner and sculptor after she returned to the United States and was living in Philadelphia. Bing’s missive updates her on the casting of The Wretched into bronze and mentions that people admire the works she left in Paris and are “anxious to see some more,” which, he believed, “will be a good thing for the sake of spreading out your reputation in this country.”27

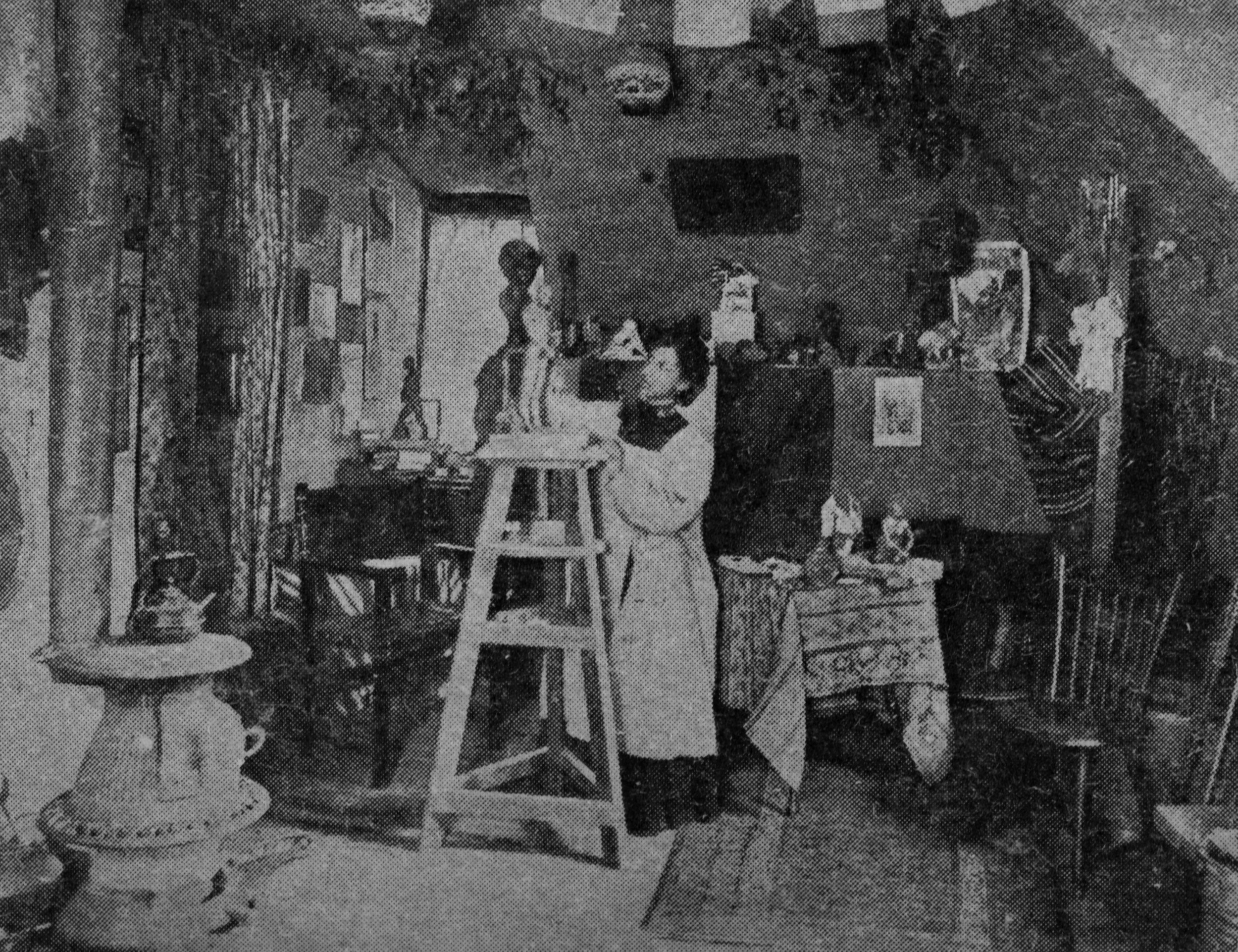

Unfortunately, most of the small groups Bing mentioned would be lost in the devastating 1910 fire, but several previously unknown photographs in the scrapbook now give us a better understanding of these ambitious sculptures from her Paris and Philadelphia studio spaces. Three photographs show her large-scale figures in an atelier, possibly at the Académie Colarossi, the art school she attended along with a range of national and international students, including Camille Claudel, Alphonse Mucha, and Amadeo Modigliani.28 Two life-sized studies, in particular, attest to the figural prowess Fuller attained in Paris. A seated female form with a rounded abdomen and heavy breasts suggests work from a live model, as does a seated male figure’s deep-set eyes and mustache (fig. 7). Until the scrapbook’s discovery, Francis O’Donnell’s 1907 seven-page article in The World To-Day was considered the sole source for the few remaining images of her early pieces. In the scrapbook, we can now see these works in her studio and exhibition spaces, giving access to display and curation choices as well (fig. 8).

The photographs in the scrapbook document no-longer-extant sculptures that trace Fuller’s early career and illuminate her extraordinary range of topics and techniques. Two studio images show her ambitious competition entry for a Monument to William McKinley (c. 1905) in the center background on a table (figs. 8, 9). Another photograph documents a 1905 exhibition in Philadelphia with pieces arranged on multiple levels (fig. 10).29 Her early works deal with religious subjects, like John the Baptist (c. 1900), a theme to which she would return in her later career, and French topics, like Brittany Peasant (c. 1902), which she would recreate after the fire. Several pictured sculptures also reference literary or mythological subjects. Even when treating more traditional subjects, Fuller reinterpreted them to maximize drama, choosing to depict Oedipus in the act of self-mutilation or wrestlers trying to throw each other over a cliff. More experimental works, like Wildfire (Feux Follets) (c. 1901), on the left on the back table in the studio, respond to modern French art movements like Symbolism—the late nineteenth-century artistic movement inspired by dreams, imagination, and emotion—one of the many styles Fuller explored.30 Her ability to capture a sense of mysterious portent in a complicated composition of expressive swirling lines verges on abstraction and demonstrates her eclecticism and resistance to a singular style.

Other images and newspaper articles document her award-winning diorama series created for the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Virginia in 1907.31 A grainy halftone image, perhaps clipped from a newspaper, shows Fuller at work on figures for one of fourteen dioramas, which no longer exist, along with numerous preparatory drawings on the wall (fig. 9). At least three of the twenty-four figures for the first diorama, Landing of the First Twenty Slaves at Jamestown, appear in the studio, and subsequent articles show her assisting in ambitious programs that encompassed over 130 clothed and wigged individuals, painted backdrops, and architectural models. This was Fuller’s first major commission in the United States, and her scrapbook preserves the process of creation as well as the project’s completion and subsequent acclaim.

The scrapbook also reveals Fuller’s interventions in her biography through the newspaper articles she preserved and the notations she added. The pages are crowded, particularly those dating to her time in Paris, when she preserved, with palpable excitement, even the briefest notices that included her name. Although scholars knew the French press had covered her exhibitions, the scrapbook assembles more notices in French and US publications than suspected, even from before her exhibition at Art Nouveau. These include mentions from the trendsetting Galerie B. Weill’s 1901 inaugural show, where Fuller shared the space with several promising artists, including Aristide Maillol, in the same location where Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso would have exhibitions the following year.32 As noted by Gustave Coquiot and later translated in the US press, “Mademoiselle Warrick astonishes one by the audacity of her compositions: she shows herself a true sculptor, endowed with true imagination. She should be well received, for real sculptors are rare.”33 A journalist for L’Action Française compared her figures’ expressions to works by Honoré Daumier, while a critic for Le Petit Bleu de Paris linked her sense of movement to Rodin and Medardo Rosso.34 These rare clippings demonstrate her popularity abroad and at home and enrich our understanding of Fuller’s recognition.

In her personal annotations, Fuller was more critical of reactions in the US press. When the French press referred to her as Creole, she apparently made no effort to correct them. Yet, when the American press stereotyped her past, she vehemently protested, at least in her private scrapbook. For example, when O’Donnell commented that her family was “poor,” she crossed out the word, leaving, “Her people have all been of the laboring class.”35 Fuller’s edit refused the association with poverty but acknowledged her family’s trajectory from the working class to middle-class entrepreneurs.

When another writer attempted to exoticize her ancestry, she crossed out the following passage with three thick pencil lines (see fig. 3):

The lineage of Miss Warrick is more than romantic. Her parents and grandparents—one of the latter, Henry Jones, being a leading caterer—were of Philadelphia. A grandfather on her father’s side was an Episcopalian minister of Portsmouth, Va., the great-grandfather being an Englishman named Warrick—hence her name. A strain of Indian blood of which she is proud comes down to her from the fourth generation, and influences her features and expression a very little, and very pleasantly. Going back on the other side she can claim for a great-great-grandfather an African princess who was legally married by a member of a prominent Germantown family—there was even a certificate to prove it.36

Fuller clearly did not want to be romanticized, although she could not prevent the story of the African princess appearing in several later articles. The writer continued to discuss her current social restrictions, which Fuller also crossed out, adamantly rejecting the negative assessment of her racial status. She also put a question mark at the end of this paragraph written by O’Donnell:

I have said the Meta Warrick is a descendant of slaves. She is proud of it. Especially pleased is she with the knowledge that royal African blood runs in her veins; she believes it may account for the wild fervor which she injects into everything she does, and especially what has been termed the morbid, horrible side of her art.37

US writers did not relate her art to current European trends and instead wanted to attribute her style to her African origins, whereas Fuller herself attributed her choices to her youthful interest in the macabre and the tortured works of Rodin.38

A writer for The North American newspaper did capitalize on her connection with Rodin, but he also highlighted her race. The article “Philadelphia Mulatto Girl’s Statuary Weird as Rodin’s” featured two works, Man Eating His Heart and The Wretched, both exhibited in Paris (see fig. 5). In the former, the journalist saw the torment of Fuller’s African American ancestors, while in the latter, he perceived feminine touches. He declared, “Turn it any way you chose, glance at but a part of it, and still you perceive clearly that it is the despairing remorse of a woman’s heart.”39 Fuller’s own later description of The Wretched to a museum curator complicated the journalist’s gendered reading by claiming the sculpture shows many different forms of human anguish:

A woman suffering from loss—say, the loss of her child; a man suffering from shame; an old man, from poverty in his old age; a woman, from distress of mind; a child, from some hereditary malady; a man who realizes that he can never fulfill the task before him; and topping them all, the philosopher who suffers from sympathy and understanding.40

Fuller’s universal and psychological interpretation more closely echoed those of the French reviewers who praised her imagination and innovation. By refusing the constraints of biographical interpretation, she demanded equal treatment with her fellow artists both in Europe and the United States.

Fuller would spend her career asserting her agency. She had returned from her Paris sojourn expecting recognition or, at least, the ability to make a living at her métier. However, American galleries claimed collectors only wanted European artists, and her career stalled. As Ater surmised, “It is probable that race played as significant a part in her rejection by the leading galleries as did gender.”41 Without the patronage of the white US art world, Fuller used her scrapbook to preserve a more personal version of her career and the positive affirmations she received in Paris, keeping it with her even after losing so much. By collecting articles, photographs, and writing, Fuller used her scrapbook to communicate loudly and clearly in her voice. As a result of this discovery, further scholarship can amplify the artist’s dialogue with European art practice, investigating colleagues, institutions, and critiques in turn-of-the-century Paris art circles, benefiting from the artist’s interventions in the scrapbook to explore her story, and using her own marks as signposts.

Cite this article: Erika Schneider, “Asserting Agency: Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Scrapbook,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15090.

Notes

- Scrapbook of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Collection of the Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University, gift from Carnel Hoover (hereinafter Fuller Scrapbook). I am indebted to the Danforth Art Museum’s director and curator Jessica Roscio and the collections manager Rachel Passannante for their generosity in sharing the scrapbook with me and answering questions about Fuller. Research for this article was funded by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s Scholars-in-Residence Program and assisted by a CELTSS Writing Retreat. My thanks to Elaine Beilin, Emily Burns, Kate Crawford, Erin Pauwels, and Annika Fisher for their feedback, which helped shape this article. Unless otherwise stated, translations are my own. ↵

- My research on the Harlem Renaissance is most informed by Davarian L. Baldwin and Minkah Makalani, eds., Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013); Brent Hayes Edwards, The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003); George Hutchinson, ed., The Harlem Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007); David Driskell, David L. Lewis, and Deborah Willis Ryan, eds., The Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America (New York: Harry N. Abrams / Studio Museum, 1987); Wil Haygood, I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance at 100 (New York: Rizzoli, 2018); Theresa Leininger-Miller, New Negro Artists in Paris: African American Painters and Sculptors in the City of Light, 1922–1934 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001); Amy Helen Kirschke, ed., Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance (Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2014); and Barbara McCaskill and Caroline Gebhard, eds., Post Bellum, Pre Harlem: African American Literature and Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2006). ↵

- The Danforth received the scrapbook in April 2021. Carnel Hoover has not answered further questions from the curator, and current descendants did not express interest in the scrapbook. Several letters demonstrate that Fuller’s son was looking for the scrapbook after his mother’s death in 1968. Solomon Fuller Jr. Correspondence, Meta Warrick Fuller Papers, box 1, Archives of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, NY (hereinafter Fuller Papers). I plan to consult Sylvia G. L. Dannett Papers, Archives, Heritage Hall, Livingstone College, Salisbury, NC. ↵

- Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 136–37. See also Carla L. Peterson, Black Gotham, A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011); and Jocelyn K. Moody, ed., A History of African American Autobiography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021). For an illustrated history of American scrapbooks, see Jessica Helfand, Scrapbooks: An American History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008). ↵

- Besides Ater’s several publications on Fuller, such as her major monograph Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), other publications include include Julie Bucknor Armstrong, “‘The People . . . Took Exception to Her Remarks’: Meta Warrick Fuller, Angelina Weld Grimké, and the Lynching of Mary Turner,” Mississippi Quarterly 61, nos. 1/2 (Winter–Spring 2008): 113–42; Caitlin Beach, “Meta Warrick Fuller’s Mary Turner and the Memory of Mob Violence,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 36 (May 2015): 16–27; W. Fitzhugh Brundage, “Meta Warrick’s 1907 ‘Negro Tableaux’ and (Re)Presenting African American Historical Memory,” Journal of American History 89, no. 4 (2003): 1368–1400; Lisa Farrington, Creating Their Own Image: The History of African American Women Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Judith Nina Kerr, “God-Given Work: The Life and Times of Sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877–1968” (PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, 1987); Kathy A. Perkins, “The Genius of Meta Warrick Fuller,” Black American Literature Forum 24, no.1 (Spring 1990): 65–72. I presented “Meta Space and Mimesis: Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Studios” at the colloquium Gustave Courbet, l’atelier sans fin, organized by the Musée et Pôle Courbet and Institut national d’histoire de l’art, in Ornans, France, March 11–12, 2022, and I continue to work on this topic. ↵

- Two major exhibitions in the last three years showcased Fuller’s sculptures. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, featured Danse Macabre (1914; Danforth Art Museum) and plaster versions of Emancipation in their expansive 2019–21 exhibition Women Take the Floor, while the Danforth’s small painted plaster model of Ethiopia (1921) made its debut at the fifty-ninth Venice Biennale 2022 exhibition, Milk of Dreams, which focused on female artists from around the world. ↵

- Although substantial research exists on African American artists’ international connections after World War I, there is less on the earlier period. See Michael Fabre, From Harlem to Paris: Black American Writers in France, 1840–1980 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991); Margaret Crumpton Winter and Rhonda Reymond, “Henry Ossawa Tanner and W. E. B. Du Bois: African American Art and ‘High Culture’ at the Turn of the Century,” in McCaskill and Gebhard, Post Bellum, Pre Harlem, 231–49. Based on the writings of French art historian Jean Laude, Joshua Cohen posits that unless there is documentation, resemblance is not enough to ascribe influence, a complicated term in the context of African art and modernism. I am grateful to Emily Burns for alerting me to the nuances of “influence” in Joshua Cohen, The “Black Art” Renaissance: African Sculpture and Modernism across Continents (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2020), xiii–xiv, 94–97. ↵

- Adrienne Childs argues that contemporary female artists use figuration to challenge the academic canon. As she writes, “By injecting the black female body, often their own, into modernist compositions, they upended and claimed a place in the ongoing dialogue about representation and the female body.” Adrienne L. Childs, Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Phillips Collection in association with Rizzoli Electa, 2019), 71. ↵

- Augusta Savage credited Fuller as a mentor during their time on Martha’s Vineyard and subsequently curated her own career in the pages of her scrapbook. Augusta Savage Papers, box 2, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, NY. See also Kristen Pai Buick, “Monu*ment*ality: Edmonia Lewis, Meta Fuller, Augusta Savage and the Re-Envisioning of Public Space,” in Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman, ed. J. M. Hayes (London: Giles, 2018), 40-57. ↵

- Several authors address the vital contributions of nontraditional African American narratives, specifically Lois Brown, Frances Smith Foster, Cherene Sherrard-Johnson, and Andreá Williams, whose work appears in Jocelyn K. Moody, ed., A History of African American Autobiography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021). ↵

- “Mr. W. M. Dorsey kindly placed his unique scrap-books at my disposal.” W. E. B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1899), iv. According to the Cheyney University of Pennsylvania Archives, subjects include African Americans, Africa/Africans, Native Americans, politics, religion, and art. William H. Dorsey scrapbook collection, University Archives, Leslie Pinckney Hill Library, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania. ↵

- Passannante observed that Fuller put photographs at the end of the scrapbook and articles at the beginning, but at some point, she began to merge the two types of documents. ↵

- As the editor of The Foundation, Frank W. Clelland may have intended to write an article about Fuller. Clelland to Fuller, October 11, 1938, “Correspondence, 1930s,” Fuller Papers. ↵

- Roger Lane, Richard Dorsey’s Philadelphia and Ours: On the Past and Future of the Black City in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991). ↵

- Sylvia Dannett, “Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller,” in Profiles of Negro Womanhood (Yonkers, NY: Educational Heritage, 1966), frontispiece, 2:31–46. ↵

- Margaret Rose Vendryes wrote that antebellum painter Robert Duncanson “claimed the right, as an artist and as a freeman, to skirt or transcend racial classifications when he so chose”; see Vendryes, “Race Identity / Identifying Race: Robert S. Duncanson and Nineteenth-Century American Painting,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 27, no. 1 (2001): 90. Henry Ossawa Tanner, Fuller’s family friend, also eschewed the limitations of race by choosing to live in France. See Anna O. Marley, ed., Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2012); Naurice Frank Woods Jr., Henry Ossawa Tanner: Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy (London: Routledge, 2017). Edmonia Lewis offered another pioneering model as a biracial person who chose to live abroad. Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010). ↵

- “A travers l’art, sculpture: Mlle Meta Warrick,” La Fronde, June 26, 1902, 2. ↵

- Ater, Remaking Race and History, 23. ↵

- William Francis O’Donnell, “Meta Warrick, Sculptor of Horrors: The Negro Girl Whose Productions Are Being Compared to Rodin’s,” World To-Day 13, no. 5 (November 1907): 1140. ↵

- Gabriel Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1986), 235, 237, 280n40. ↵

- Ater mentions that she borrowed a catalogue from Weisberg (Remaking Race and History, 148n62). ↵

- “{L}e sens de la forme, l’originalité de la vision, l’audace tranquille et la force d’expression.” Edouard Gerard, “Oeuvres de Mlle Meta Warrick: Exposées à l’Art Nouveau Bing” (1902), vi; translated in “Meta Vaux Warrick, Sculptor of Philadelphia in Illustrated Lecture, on Art and Life in Paris, the Beautiful” (Washington, DC: Berean Baptist Church, May 17, 1905), Fuller Scrapbook. ↵

- The stamp marked “5c&10” suggests the sculptor received the poster in the mail. She also kept an invitation card for the June 2 opening reception. ↵

- “Une jeune artiste américaine, miss Meta Warrick, expose des sculptures d’un caractère dramatique saissant, presque visionnaire, en même temps que d’une très puissanate et très savante exécution.” Arsène Alexandre, “Expositions Renoir et miss Warrick,” Le Figaro, June 23, 1902, 5. ↵

- “Elle a vingt ans à peine; et il y a déjà plus que promesses dans ouvrages. Même ils étonnent par les plus rare qualités. . . . Il faut aussi de la hardiesse, oser s’exprimer librement, et ne pas faire de concessions aux mannières convenues de voir et de sentir. Sur la jeune artiste ne pêse aucun dogme d’Ecole. Elle médite, elle rêve, elle travaille sans que la tyrannie des formules l’intimide.” “A travers l’art, sculpture,” 2. ↵

- Femina no. 27 (March 1, 1902): 76. The second undated review reads: ”. . . une recherche louable du mouvement rare et une préoccupation amusante de l’effet brutal. Le plus brillant avenir semble assuré à cette artists douée de rares qualités.” Femina no. 37 (August 1, 1902): vii. Translated in “Meta Vaux Warrick, Sculptor of Philadelphia” as “An artist of rare qualities, whose future is assured.” ↵

- Samuel L. Bing to Meta Vaux Warrick, January 6, 1903, Fuller Scrapbook. ↵

- Odile Ayral-Clause, Camille Claudel: A Life (New York: Abrams, 2002). The preparatory sketches on the back and wainscot appear similar to documented photographs of the Académie Colarossi. ↵

- “What can be identified here are: Sylvia, Procession of Arts & Crafts, Wrestlers, Peeping Tom, Death in the Wind, Man with Thorn in Foot, Secret Sorrow, Portrait from Memory of the late William Thomas, Silenus, Primitive Woman, Oedipus, The Bear-trap, Urn (5 Handled)/Jardiniere, and Brittany Peasant.” Rachel Passannante, email to the author, February 11, 2022. ↵

- Symbolism resists singular definition. See Robert Goldwater, Symbolism (New York: Harper and Row, 1979); Michelle Facos, Symbolist Art in Context (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009); Sharon Hirsh, Symbolism and Modern Urban Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); Allison Morehead, Nature’s Experiments and the Search for Symbolist Form (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); Rodolphe Rapetti, Symbolism, trans. Deke Dusinberre (Paris: Flammarion, 2005). On American art and Symbolism, see Charles Eldredge, American Imagination and Symbolist Painting (New York: Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, New York University, 1979). ↵

- For more on the Jamestown commission, see Ater, Remaking Race and History, 37–72; Brundage, “Meta Warrick’s 1907 ‘Negro Tableaux’”; and Kerr, “God-Given Work,” 147–51, 171–84. ↵

- “Mlle Warrick exhibited some promising sculptures. . . . Whatever became of her?” Berthe Weill, Pow! Right in the Eye: Thirty Years Behind the Scenes of Modern French Painting, trans. William Rodarmor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 17. Fuller preserved the catalogue, though there were no sales. She also kept a 1902 exhibitor card from the Union des femmes peintres et sculpteurs annual exhibition at the Grand Palais. ↵

- “Mademoiselle Warrick nous étonne par l’audace de ses petites compositions; elle se révèle comme un sculpteur savant et plein d’imagination,—qu’elle soit bien accueillie, car les bons sculpteurs ne sont pas légion.” Gustave Coquiot, preface to Exposition inaugurale organisée par P. Mañach à la Galerie B. Weill, du 2 au 31 décembre 1901: Bocquet, Durio, Girieud, Launay, Mlle Warrick, Maillol, de Mathan (1901); translated in “Meta Vaux Warrick, Sculptor of Philadelphia.” ↵

- “Mlle Warrick a une imagination très singulière, servie par un don d’expression qui fait songer à Daumier.” L’Action Française, March 15, 1902, 551. “Elle relèverait de Rodin et de Rosso par le mouvement qu’elle cherche à donner à sa sculpture.” “L’exposition de sculpteurs de Mlle Meta Warrick à l’Art Nouveau Bing,” Le Petit Bleu de Paris, June 22, 1902, 3. ↵

- O’Donnell, “Meta Warrick, Sculptor of Horrors,” 1141. Joyful photographs also document Fuller’s bathing costumes, hats, and frivolity in Atlantic City. Fuller Papers. ↵

- “Afro-American’s Art,” Philadelphia Record, February 5, 1905, n.p. ↵

- O’Donnell, “Meta Warrick, Sculptor of Horrors,” 1141 ↵

- O’Donnell, “Meta Warrick, Sculptor of Horrors,” 1142. The Rodin Museum Archives preserves a letter of introduction and Fuller’s calling card. Fuller’s scrapbook contains Rodin’s inscribed calling card. ↵

- “Philadelphia Mulatto Girl’s Statuary Weird as Rodin’s,” North American, 1903. ↵

- Meta Warrick Fuller to Clifford R. Dolph, February 13, 1949, Alma Spreckles Correspondence, Archives, Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, WA, cited in Ater, Remaking Race and History, 23. ↵

- Ater, Remaking Race and History, 24. ↵

About the Author(s): Erika Schneider is Professor of Art History in the Art & Music Department of Framingham State University.