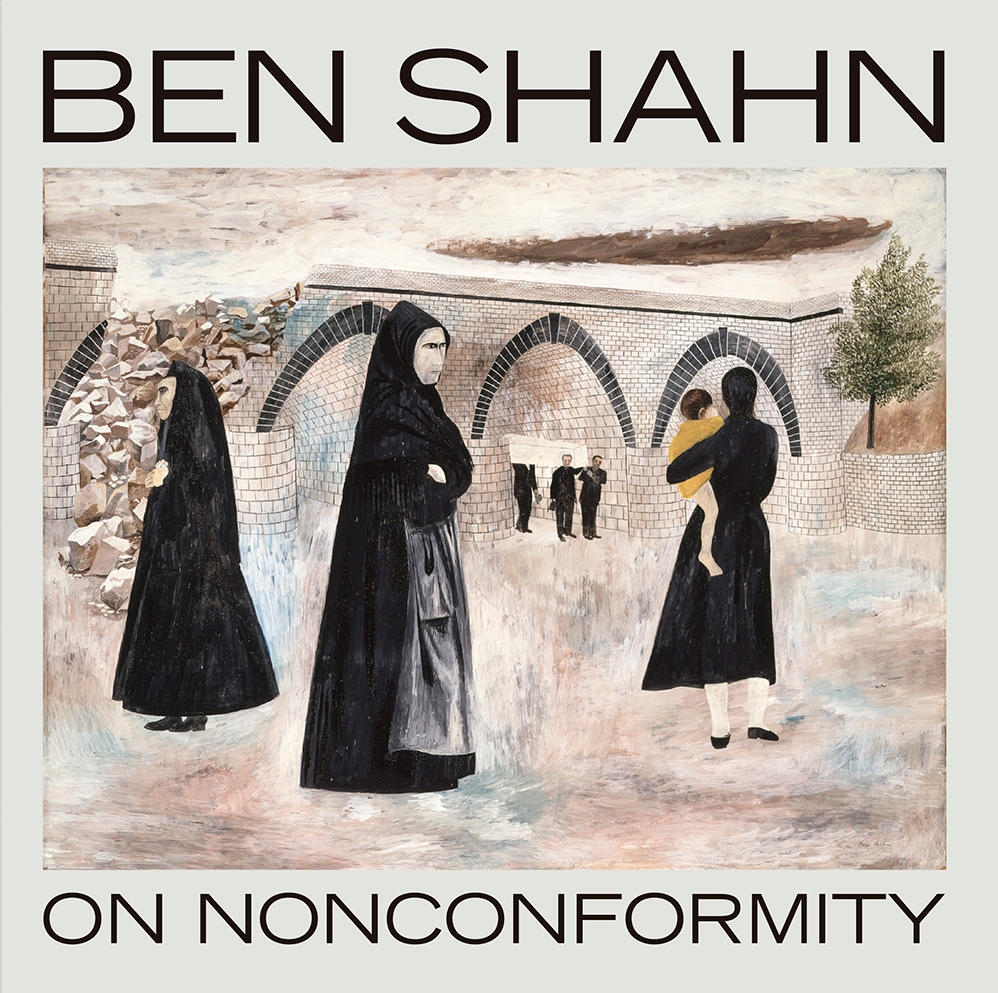

Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity

PDF: Mintie, review of Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity

By Laura Katzman, with contributions by Beatriz Cordero Martín, Christof Decker, and John Fagg

By Laura Katzman, with contributions by Beatriz Cordero Martín, Christof Decker, and John Fagg

Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2023. 288 pp.; 193 color illus.; 89 b/w illus. Available in Spanish and English. 45€. (ISBN: 978-84-8026-650-5)

In 1956, American artist Ben Shahn (1898–1969) delivered the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard University. In these talks, later published as The Shape of Content, Shahn argued that the artist plays a central role in society as a “dissident” who is “always able to see the configuration of the future in present things [and] presses for change.”1 Shahn’s vision of artists as agents of change has numerous echoes in art practice today, from Zanele Muholi’s visual activism to Tania Bruguera’s Arte Útil, among many others. The contemporary relevance of Shahn’s work and ethos is the subject of the recent exhibition Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid and the accompanying catalogue, which offers a rich proxy for those unable to see the exhibition in person.

The catalogue opens with an essay by curator Laura Katzman, professor of art history at James Madison University and a leading Shahn scholar. Katzman’s text introduces Shahn and establishes the framework for the exhibition. Born in what is now Lithuania to a Jewish family, Shahn immigrated to the United States as a child and became a major practitioner of socially conscious art from the 1930s until his death in 1969. During his prolific career, Shahn created works across media that were seen and exhibited broadly, from the walls of union halls to the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Given the current interest in activist art practices and the fact that there has not been a major retrospective of Shahn’s work in a Western museum since 1978, Katzman argues that the time is ripe for a new appraisal of the artist.2 This reexamination of Shahn’s work revolves around two ambitious questions: “What did social justice look like to Shahn? What remains relevant today?” (15).

Katzman offers initial answers to these key questions. She describes Shahn’s approach to creating socially conscious art as relying on “real-world particularities . . . to create universal symbols for his time” (33). A prime example of Shahn’s method is Defaced Portrait of 1955. This tempera painting shows a bald white man with a puffed chest clad in a uniform laden with medals. However, the medals are largely obscured by angry black Xs that Shahn has painted across the torso. While Katzman speculates that the figure is based on Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, the image conjures other cruel fascist leaders of the World War II era, and Shahn’s forceful defacement suggests the repudiation of their continued rule in the postwar period. Given contemporary concerns about democratic backsliding and the rise of a new cohort of autocrats, the pointed symbolism of Defaced Portrait has lost none of its original power.

While effective in certain instances, Shahn’s attempt to create “universal symbols” also had its pitfalls, as Katzman and others, such as Cécile Whiting, argue.3 This mode of expression occasionally led Shahn to downplay cultural, ethnic, and racial differences among groups he represented to achieve what he, as a Jewish American man, believed to be a shared vision of humanity. Along these lines, Katzman observes that Shahn tended to picture men more frequently than women, and she critiques him for primarily representing women as “protective mothers, worried wives, grieving widows” (32). This narrow domestic view ignores the fact that women increasingly played important roles in the workplace and politics during Shahn’s lifetime. Indeed, Shahn’s second wife, Bernarda Bryson Shahn, was an accomplished artist and labor organizer.

While acknowledging these shortcomings, Katzman and the other contributors to the catalogue emphasize that Shahn’s oeuvre remains relevant to our current moment. This theme runs through the three additional essays that appear in the catalogue, which are written by an international group of scholars: John Fagg (UK), Christof Decker (Germany), and Beatriz Cordero Martín (Spain).

In his essay, Fagg examines Shahn’s lifelong aim of creating art that was “at once of and for working people” and offers an overview of some of Shahn’s most celebrated works related to the cause of labor (35). These include his series of gouaches about the wrongfully imprisoned union organizer Tom Mooney (executed 1932–33), his public mural The Meaning of Social Security (1940–42) in the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building in Washington, DC, and his line drawings depicting an Illinois mining disaster for Harper’s Magazine (1948). More important, Fagg points out that while Shahn excelled at making art that captures the values of work, his output often failed to earn the interest or admiration of working people. The challenge of developing politically salient, accessible art is one that contemporary activist artists continue to face today. While Shahn was not always successful in this arena, Fagg posits that there remains much to be gained from studying Shahn’s experiments with different media and frequent reliance on collaboration in developing art that reckons with shifting notions of work.

In contrast to the broad thematic scope of Fagg’s essay, Decker focuses on a small set of posters that Shahn created during his tenure at the Office of War Information (OWI) during World War II. As Decker notes, Shahn was part of a creative team tasked with responding to the disturbingly effective posters circulating in Nazi Germany and defining what a “democratic idea of propaganda” might look like (44). Efforts to realize this objective led to equal amounts of experimentation and rejection. As Decker points out, only two of Shahn’s posters for the OWI were ever circulated: This is Nazi Brutality (1942) and We French Workers Warn You (1942). While these published posters are two of Shahn’s best-known works, his rejected designs also offer important insight into Shahn’s politics and those of the period. One of the unused posters is Our Manpower (1943), which Shahn produced with poet Muriel Rukeyser. The poster depicts two welders, one Black and one white, working side by side with text below that reads, “1/5 of our strength must not be lost through discrimination” (47). Shahn and Rukeyser’s call for interracial solidarity in support of the war effort, while clear and persuasive, was rejected by the OWI and indicates the sharp limits of crafting a “democratic idea of propaganda” in the 1940s. While the OWI was not always receptive to Shahn’s designs, Decker values them for prioritizing “inclusion as a precondition for the common goals of freedom” (49), a visual ethic that resonates in several contemporary projects. An excellent example is the 2018 reimagining of Norman Rockwell’s celebrated Four Freedoms posters by Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur, members of the For Freedoms artist organization that “centers art as a catalyst for creative civic engagement, discourse, and direct action,” a mission that Shahn surely would have supported.4

While the first two essays center on Shahn’s artistic output, the final essay by Cordero Martín (with Katzman) explores his participation in debates on art practice in the United States during the Cold War. In broad strokes, these disputes pitted the realist work of Shahn and others against emergent abstract and nonobjective approaches championed by artists like Robert Motherwell and critics like Clement Greenberg. Given that Shahn was a prolific writer and lecturer, Cordero Martín and Katzman focus on exchanges between Shahn and other artists at MoMA, which was “a focal point for the realism-abstraction debates” (52). In addition to highlighting a predictably barbed spat between Shahn and Motherwell at MoMA in 1949, the authors examine Shahn’s more ambiguous statements on Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (on loan to MoMA from 1939 to 1981) at a conference in 1947. While Shahn admired Picasso and Guernica, he faulted the celebrated work for not speaking to the average viewer, who would not possess, in his opinion, “the backlog of critical references” needed to untangle its message (57). Shahn’s comments on Guernica are pertinent not only in light of the current exhibition taking place at the Reina Sofía, where Guernica is now on display, but also because museums remain central arenas for and actors in aesthetic and political debates. While occasionally fractious, these dialogues underline the crucial role of artists and museums in shaping civic discourse today.

A generous section of color plates follows the essays and is organized according to the thematic sections of the exhibition. Each group of plates is preceded by a short text by Katzman that introduces the central concept that unites the selected works and situates them within Shahn’s larger career. An excellent feature of the plates section is that it includes many of the photographs to which Shahn turned in producing his paintings, drawings, and prints. For numerous works, Shahn relied on his own photographs as inspiration. For example, the gouache-on-board painting Handball (1939) appears alongside two photographs Shahn took of Houston Street Playground in the early 1930s. Through this side-by-side comparison, readers can see how Shahn adapted elements of each photograph for his painted composition. Shahn also maintained a robust collection of press photographs that he consulted when developing new work. One of the clippings featured in the catalogue is a news photograph taken during the Spanish Civil War that shows a group of women and children huddling in a cave to protect themselves from nearby bombardments. The central figure from this clipping, a sturdy matriarch clad in black, appears in Shahn’s 1943–44 painting Italian Landscape. The dramatic shift in context between press photograph and painting was not unusual for Shahn, as Katzman argues in the exhibition and elsewhere, and suggests the tensions in his use of “real-world particularities” to craft “universal symbols for his time” (33).5

Another benefit of the plates section is that it frequently shows how Shahn’s work was circulated and seen by mass audiences. On page 102, for example, we see Shahn’s photograph Boone County, Arkansas. The Family of a Resettlement Administration Client in the Doorway of Their Home (1935), and we can notice how it was significantly cropped for reproduction in Edward Steichen’s popular exhibition catalogue for The Family of Man (1955). By highlighting the diverse contexts in which Shahn’s work circulated, from posters hung on city streets to reproductions in books and magazines, Katzman skillfully curates the plates to underline Shahn’s commitment to making art that was accessible to a wide range of audiences.

Between the probing essays and abundant illustrations, the catalogue to Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity both positions Shahn in his own time and makes the case for his continued relevance today. As Katzman argues, Shahn’s relentless examination of the social role of art and artists is what will resonate most with contemporary audiences. How practitioners today respond to these same issues will form the foundation for picturing and shaping our future.

Cite this article: Katherine Mintie, review of Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity, by Laura Katzman et al., Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18869.

Notes

- Ben Shahn, The Shape of Content (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 85. ↵

- The major retrospective Ben Shahn: Cross-Media Artist, Photograph, Painting, Graphic Art was organized in Japan in 2011 and 2012. ↵

- See Cécile Whiting, “Ben Shahn: Aggrieved Men and Nuclear Fallout During the Cold War,” American Art 30, no. 3 (Fall 2016): 3–25. ↵

- For Freedoms, “Who We Are,” accessed February 20, 2024, https://www.forfreedoms.org/about. ↵

- Laura Katzman, “Source Matters: Ben Shahn and the Archive,” Archives of American Art 54, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 4–33. ↵

About the Author(s): Katherine Mintie is the Senior Researcher in Art History at the Lens Media Lab at Yale University.