Beyond Copyright: How Does Law Impact Art?

PDF: Katz and Van Haaften-Schick, Beyond Copyright

Contributors

Katherine de Vos Devine, “Mining Raw Materials: Copyright, Contemporary Art, and False Dichotomies”

Monica Lee Steinberg, “Loopholes for Some, Taxes for Everyone Else”

Kelema Moses, “Hawai‘i Land Struggles and a Pacific Statehouse”

Amy Sara Carroll, “‘Reading like a Poet’ between the Lines of the Cultural Exemption and the Mexican Exception”

Carma Gorman, “What’s American about American Industrial Design? US Laws”

Matthew Hunter, “Insurance: Beyond Law”

Introduction

Calling the relationship between art and law “underexplored” seems, at first, counterintuitive. Thanks to famous incidents in the “culture wars” of the last century concerning censorship and free speech, art historians are well aware of the role of legislation in informing what artists make, how they get National Endowment for the Arts funding, and what is exhibited in public institutions. In addition, most art historians who publish images know from personal experience the impact of copyright and fair use on canon formation and scholarship, as they are also aware of artists and heirs who view copyright laws as crucial protection against unsanctioned copying.

This context means that our discipline has often constructed the relationship between art and law as a combative spectacle. The law is an oppressor, casting the artist as outlaw or the scholar as an intruder. This approach has been reinforced by art history’s frequent focus on the cultural conflicts captured in trials, both as they are expressed in court testimony itself and in the larger public response. The John Ruskin v. James Whistler trial over the value of labor or the recent Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith case over appropriation and licensing are landmark controversies that seem to indicate turning points in definitions of art and artists’ rights. Scholars, sometimes following a new historicist model, have found the courtroom to be a matrix from which one can tease out a number of cultural elements.

Yet what sometimes gets set aside in such accounts is the law itself as a determining system—albeit an ever-shifting one—for labor, evidence, rights, or expression. Law is an infrastructure that impacts art like other human behavior and social systems. Art for art’s sake, that is, may be a legal concept as much as an aesthetic one. The Anglo-American development of copyright law may have created the romantic concept of genius, not vice versa.1 It seems advisable to remember that the law is a humanistic enterprise as much as art history is; the judicial opinion is a literary genre.2 The laws that seemingly most directly affect contemporary art (like copyright and moral rights) are molded by wider political or economic contexts, as are artists’ motivations for committing transgressions against them.3 Katherine de Vos Devine in this Colloquium specifically asks how litigation over appropriation itself has altered art. Monica Lee Steinberg’s research on privacy laws and surveillance has emphasized special protections for artists’ social transgressions. In her contribution to the Colloquium, Steinberg examines how tax law impacts artists’ creative practices by requiring them to conform to Internal Revenue Service (IRS) guidelines while, at the same time, serving as material for critique.

One reason that the cultural power of law over art has been underexamined is that there is no specialized area of law that pertains specifically to art. The Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, intended to guard artists’ attribution rights and prevent the unsanctioned destruction or modification of artworks, among other protections, is one rare exception. Art—as practice, objects, or trade—is covered by broader laws concerning intellectual and tangible property, as well as contracts, tariffs, taxes, and other areas. As such, the subfield “art law” may be a misnomer, for it does not consist of a particular body of laws—like civil rights does, for example—but points to this messy amalgamation. Approaching art and law’s entanglements reveals myriad under-examined effects; laws that seem entirely irrelevant to art and design—zoning, taxes, liability, insurance, immigration—have greatly impacted artists and even determined what kind of art they make.

“Unseen” bias is addressed in this Colloquium by Kelema Moses, who examines the role of the law in determining architectural development in US territories. She argues that US land ownership laws introduced into Hawai‘i in 1850 eventually led to annexation, and she finds evidence of the continuing conflict between systems of property in the twentieth-century statehouse on Oahu. De Vos Devine, too, in pointing to how lawyers have misappropriated postmodernism, shows that the result is the empowerment of some artists (usually white and male) at the expense of others.4 There is also a rich area of scholarship on the ways in which art challenges legal doctrine to illuminate colonialist and hegemonic facets of law. Amy Sara Carroll’s essay for this Colloquium pursues this insight, uncovering how the alteration of trade policy under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) inspired Mexican conceptual art and poetry dissecting the treaty’s cultural reach.

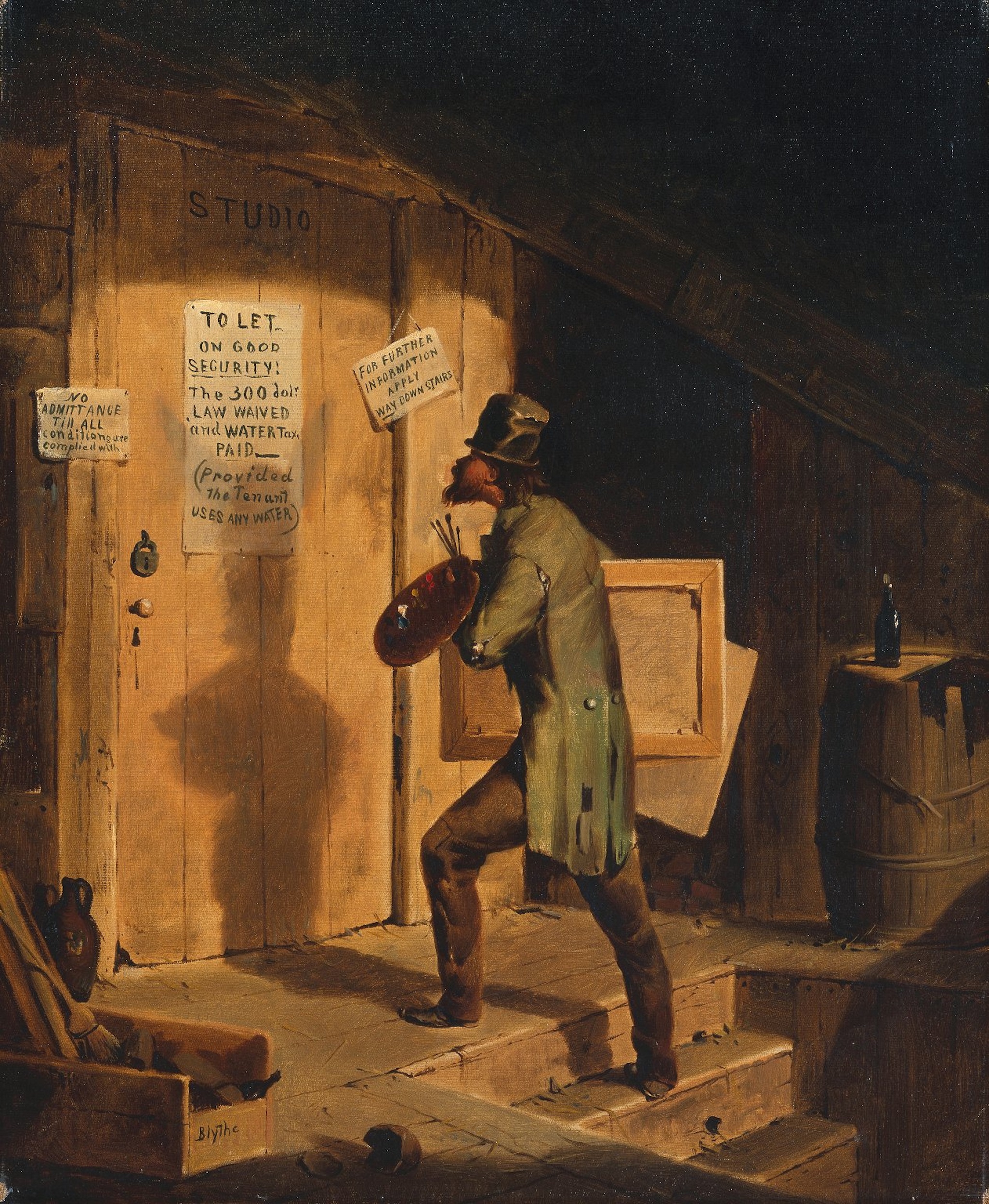

Americanists especially, as students of “nature’s nation,” may at times overlook the law because we are conditioned to turn to the natural environment to explain cultural forms instead.5 Cheryll Glotfelty points to the pitfalls of this tendency when she describes how the Utah and Nevada desert is credited for the mental frameworks of its inhabitants, such as an aesthetic appreciation of drab gray, for example. Her point is that despite the shared aridity of this region, the cultures of the two states differ dramatically because their legal systems are so different: with divergent laws for sex (divorce, prostitution, marriage), consumption and trade (alcohol, gambling, prize fighting), and land management (nuclear waste, mining, even signage).6 “Learning from Las Vegas,” like learning from Salt Lake City, requires thinking about the constraints and opportunities imposed by the law as much as by the lack of water. In this Colloquium, Carma Gorman accordingly offers a refreshingly deterministic analysis of just how pervasive and controlling patent, tax, liability, and environmental laws have been for US design. In his Colloquium contribution, Matthew Hunter tackles insurance, something regulated by the states, asserting that rather than a private act beyond the law, insurance shapes the outcomes and recourse around art production and preservation (fig. 1).

Indeed, there is a fast-growing field of scholarship investigating the intersections of art and law beyond copyright and associated artists’ rights. As Joan Kee observes, the broader landscape of laws and regulations in which artists operate and present their work can be taken as art’s surround.7 Against this backdrop, some artists, like Gordon Matta-Clark, have viewed the legal system itself as a medium. Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975) bluntly toyed with the limits of legality, as the artist knowingly trespassed into a municipal pier to incise his signature cuts in the rusted structure. The act invited reflection on the relationship between art and scale or site restrictions, contested the definition of “trespass” by illuminating the porous boundary between private property and public good, and signaled more banal but utterly relevant public safety regulations. Photographs of the municipal piers, which sheltered the homeless and were popular for queer cruising, signal more ways in which law impacts art. In the 1970s, sodomy laws were still on the books in New York State, rendering the copulating and sunbathing men in Alvin Baltrop’s photographs outlaws, pushed to Manhattan’s margins (fig. 2). Yet the site, and the legal conditions orchestrating its community as well as its dangers, served as a muse for many. Whether taken from a voyeuristic distance or capturing intimate exhibitionism, Baltrop’s images raise further questions about the ways in which privacy and consent had to be navigated by participants and photographers alike.

Cite this article: Wendy Katz and Lauren van Haaften-Schick, introduction to “Beyond Copyright: How does Law Impact Art?” Colloquium, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17362.

Notes

Wendy Katz is a member of Panorama’s Advisory Council.

- Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, “Who Owns Washington? Gilbert Stuart and the Battle for Artistic Property in the Early American Republic,” in Circulation and Control: Artistic Culture and Intellectual Property in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire and Will Slauter (Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2021): 77–117. ↵

- Robert Ferguson, “The Judicial Opinion as Literary Genre,” Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 2 (1990): 201–19. ↵

- Martha Buskirk, Is It Ours? Art, Copyright, And Public Interest (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021). ↵

- Critical Race Theory (CRT), first developed as a legal theory, has been fundamental to thinking through the concept of “artist” in the United States in terms of who is excluded from that category and from ownership of intellectual property, as well as who is censored. CRT has been employed in fields like music, dance, and performance, as well as by art historians. See Joshua Takano Chambers-Letson, A Race so Different: Performance and Law in Asian America (New York: New York University Press, 2013); Anthea Kraut, Choreographing Copyright: Race, Gender, and Intellectual Property Rights in American Dance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, “The Arena of Suspension: Carrie Mae Weems, Bryan Stevenson, and the ‘Ground’ in the Stand Your Ground Law Era,” Law and Literature 33, no. 3 (2021): 487–518; Anjali Vats, “Prince of Intellectual Property: On Creatorship, Ownership, and Black Capitalism in Purple Afterworlds (Prince In/as Blackness),” Howard Journal of Communications 30, no. 2 (2019): 114–28. ↵

- The phrase stems from Perry Miller, Nature’s Nation (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967), but it has often been applied in American studies to characterize the early republic’s egalitarian political culture and its symbolism. ↵

- Cheryll Glotfelty, “State Pieces in the U.S. Regions Puzzle: Nevada and the Problem of Fit,” in Regionalism and the Humanities, ed. Timothy Mahoney and Wendy Katz (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008): 237–50. ↵

- Joan Kee, Models of Integrity: Art and Law in Post-Sixties America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019). ↵

About the Author(s): Wendy Katz is a professor at the School of Art, Art History and Design, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Lauren van Haaften-Schick is an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, at the Center for the Humanities, Wesleyan University.