“Reading like a Poet” between the Lines of the Cultural Exemption and the Mexican Exception

PDF: Carroll, Reading like a Poet

In REMEX: Toward an Art History of the NAFTA Era, I argue that the North American Free Trade Agreement/ Tratado de Comercio Libre del América del Norte/ Accord de libre-échange nord-américain (NAFTA/ TLCAN/ ALÉNA), billed as a trilateral agreement to eliminate continental trade barriers between Canada, the United States, and Mexico, represented the most fantastical inter-American social allegory of the late twentieth century.1 Although NAFTA technically went into effect one minute after midnight on January 1, 1994, the continent’s NAFTAfication encompassed the treaty’s contentious negotiation, signing, ratification, and the fifteen years of its implementation from 1994 to 2008. Because the agreement unfolded in the wake of Mexico’s 1984 Faustian pact with the World Bank, wherein Mexico was granted a loan in exchange for its adoption of significant neoliberal reforms, NAFTA’S asymmetrical effects were anticipated: Mexico’s “economic penetration” and US exceptionalism were treated as paired foregone conclusions. Objections to the treaty subsequently assumed distinct shapes in the two nation-states.

US public debates across the political spectrum underscored factory flight and coupled NAFTA with alternate anxieties of penetration in sync with the reconfiguration of the hemispheric “War on Drugs” and militarization of the borderlands by way of a “Prevention through Deterrence” philosophy, redirecting undocumented entrants through isolated and intemperate desert zones. Mexican debates centered on threats TCLAN posed to the nation’s cultural autonomy. Lawmakers and cultural producers alike focused on the “cultural exemption.” In the treaty’s parlance, a “cultural exemption” refers to a cultural commodity or industry exempt from tariffs or regulation. In the court of public opinion, the “cultural exemption” became synonymous with the outsized role the arts were called on to play in the preservation of Mexican character.2 Technocrats of the 1980s affiliated with Mexico’s decades-long ruling party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party), slashed social services, denationalized industry, and rewrote key provisions of the constitution, laying the groundwork for what Gareth Williams dubs the “Mexican Exception.”3 They also implemented dramatic changes to the country’s arts and educational funding structures. The Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes and the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, established in 1988 and 1989 respectively, coordinated the diversification and expansion of state and private enterprise’s collaborative funding of the arts even as US federal allocations to the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) were gouged.

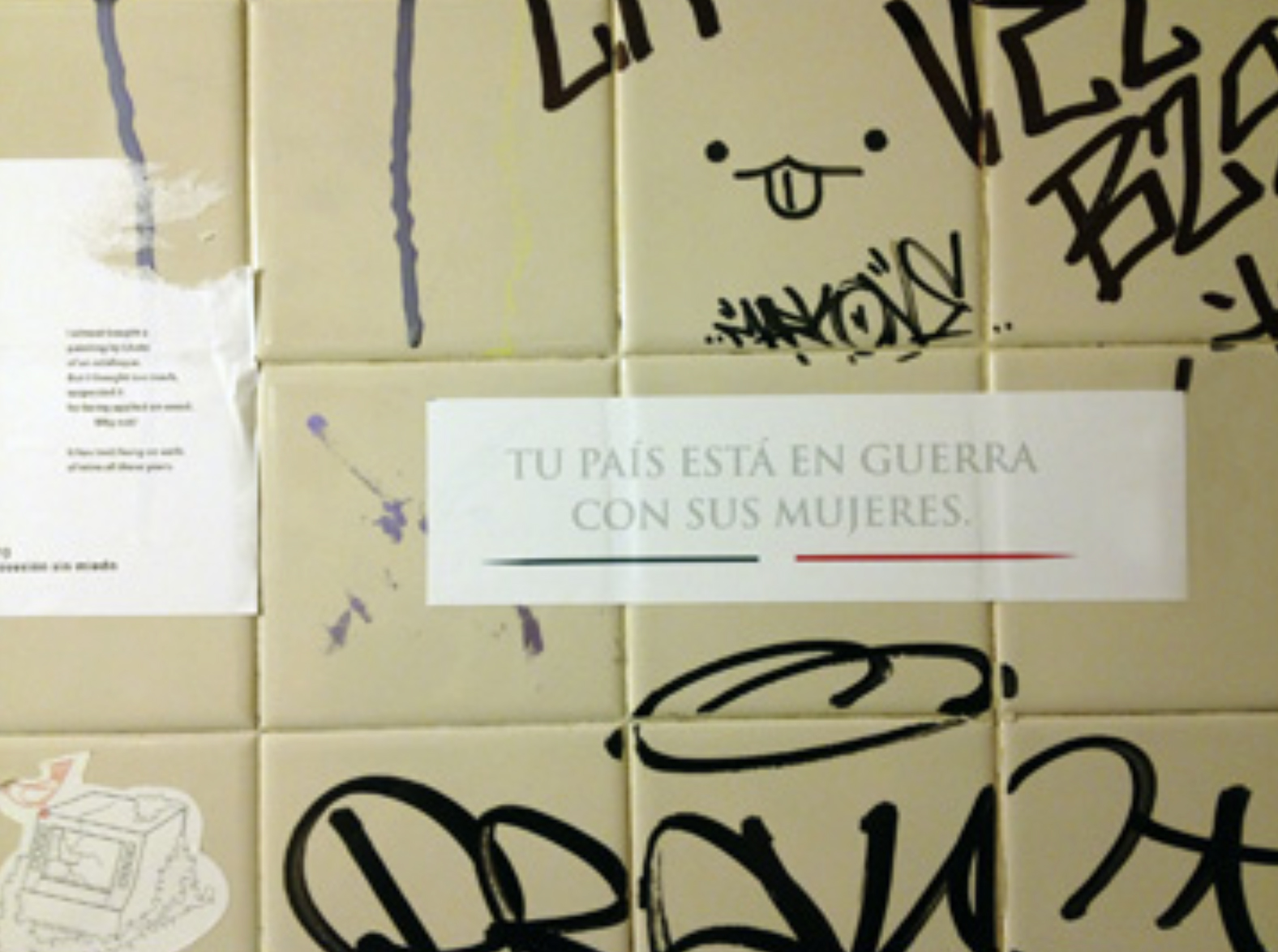

The impact of such “remedies” remains palpable: from the late 1980s onward, a particular brand of Mexican art, labeled post/neo/conceptual, was foregrounded inter/nationally. Sometimes aligned with this impulse, a critical mass of artists in Mexico City and in the Mexican-US borderlands, beneficiaries or not of the aforementioned “culture wars,” produced formally varied work, focused on the period’s reconfigurations of Greater Mexican racial capitalism and sex-gender systems—what I “read like a poet” in REMEX as the era’s aggravated “Conceptual-isms.” Consider the Border Arts Workshop/ Taller de Arte Tranfronterizo’s insistence in public debates on the substitution of the word “undocumented” for “illegal”; Teresa Margolles’s recycling of narco-messages and inter/national news on Mexico’s escalating narco-violence; or Lorena Wolffer’s culture-jamming sticker, “EL GÉNERO ES VIOLENCIA.” Insofar as the Spanish género refers to both gender and genre, Wolffer’s aphorism, apiece with her general turn to languaging in public, aligns with inter/national jurisprudence’s roughly contemporaneous recognition of “femicide,” the word and phenomena (fig. 1). Simultaneous translation: “EL GÉNERO ES VIOLENCIA” corroborates the imperative to read gender itself as a genre, its structural violence enshrined in both the period’s recycled script of colonial encounter and in quotidian interactions choreographing (citizenship) subjectivity.

Heightened attentions to market-statecraft were, of course, not confined to the visual arts. As a study in contrasts, while Octavio Paz in the PRI’s service touted the merits of free trade for Mexico, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation’s first communiqué, released to coincide with the treaty’s inauguration, remains one of the period’s most formally innovative statements of opposition to Mexico’s euphemized “democratic transition.” Zapatismo—the movement spanning, but not limited to, the communiqué, the intergalactic Encuentro, and the ski mask—leverages language (“our word is our weapon”) to push back against the negative socioeconomic consequences of the spectacle of the market-state’s extractivist preoccupations. The Zapatista communiqué lay the groundwork for a corpus of work spanning the arts, whose genealogy half-rhymes with Luis Camnitzer’s diagram: “Dada–situationism/ Tupamaros–conceptualism.”4 Camnitizer’s assemblage signals the entanglement of the Uruguayan Marxist-Leninist National Liberation Movement known as Tupamaros, active during the 1960s and 1970s, and a uniquely Latin American conceptual art. Striking a similar chord, Mari Carmen Ramírez argues for a distinction between Latin American conceptualisms and prior understandings of US/Eurocentric articulations of neo/post/conceptual practices when she asserts more generally, by way of “the neologism contextura, that (art) historians must account for the “context” and “texture” of any given artwork’s production and reception.5

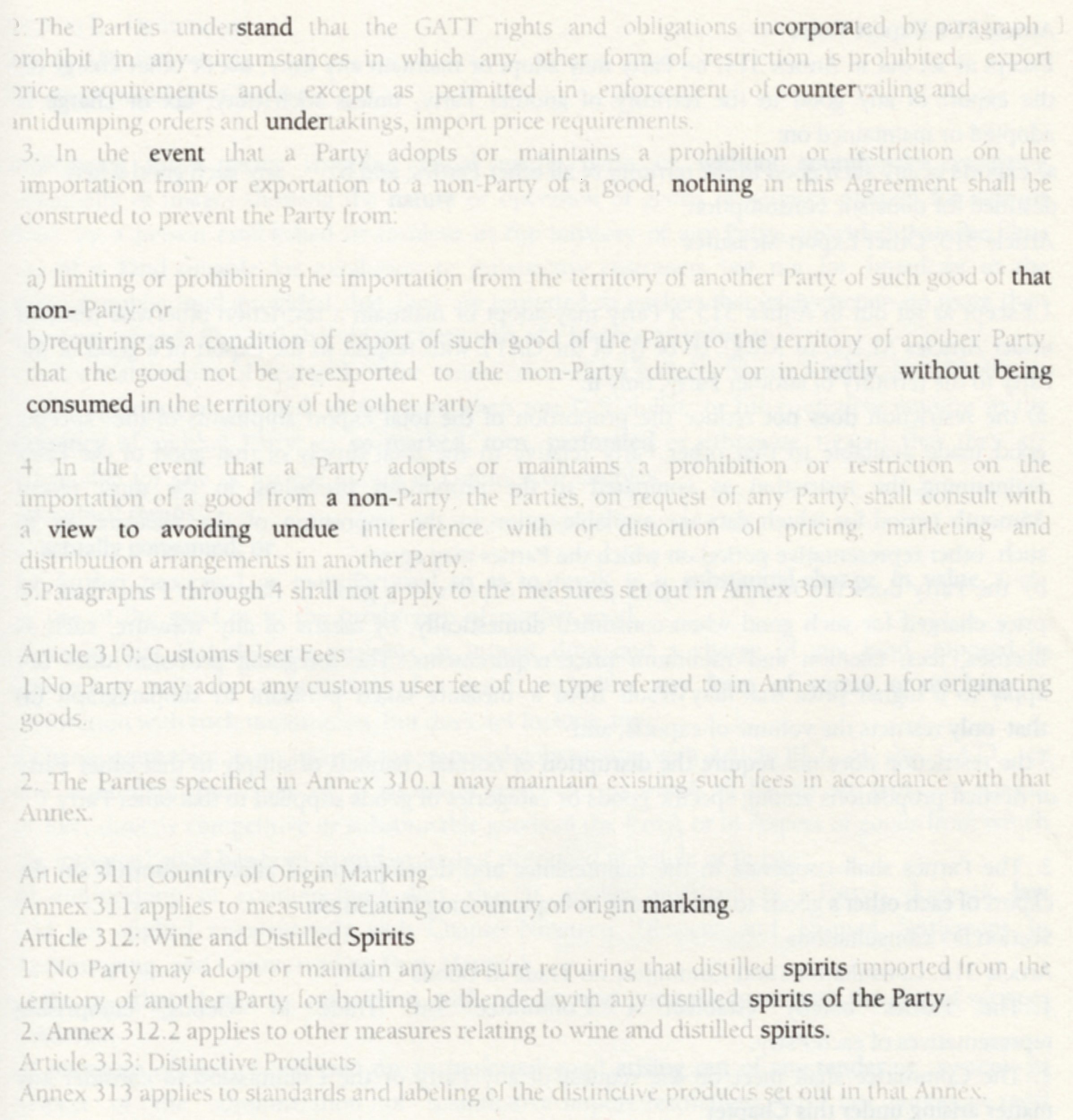

One haunting expression of the variegated contextura of NAFTAfication underscores the synergy between experimental practices in the literary and visual arts responding to governmentality in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The Mexican poet Hugo García Manríquez returns us to the source—text—in the collection for which he is best known, A-H: Anti-Humboldt: A Reading of the North American Free Trade Agreement / A-H: Una lectura del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte.6 A-H, a key example of “disappropriation” for Cristina Rivera Garza, reproduces and “treats” NAFTA and TLCAN in full—meaning, the author sculpts concrete poetry out of the heightened contrast between the accord’s standard black font and portions of that same font, grayscaled, across the Spanish and English versions of the treaty.7 The effect adds dimensionality to NAFTA/ TLCAN and introduces visual disharmony into its “Harmonized System,” so-called in economics and public policy. Alternately, shadows crisscross the insular vocabulary of the accord’s standardized numerical method of classifying traded products, reminding A-H’s readers that “géneros” in the plural also denotes goods produced, traded, bought, and sold.

Take “PART TWO, Chapter three, Section C, Articles 309-313” (fig. 2), originally devoted to regulating the sale of alcohol. García Manríquez returns the section as a two-toned hypnotic dance of “spirits” at the “Party”’s margins. One might wonder whether “Party” refers to the PRI, before registering A-H’s mutation of the original’s reference to two parties of a business transaction. Turn the book over, and “untreated” Spanish terms, like ghosts, float free of TLCAN’s surfeit of legal terminology, too, conjuring allegory’s etymology, “Other(s), speaking.” Ostensibly A-H resonates with recent projects in contemporary North American poetry, loosely aggregated under the heading of “conceptual writing” (think of the work of UbuWeb founder Kenneth Goldsmith, now widely denounced for his performance “The Body of Michael Brown,” or Vanessa Place’s Tragodía 1: Statement of Facts, a reconfiguration of the trial transcripts of cases she argued, and Notes on Conceptualisms, in which she and Robert Fitterman mark the connectivity of conceptual and allegorical writing vis-à-vis primarily US and European artistic and literary references).8 Pointedly, García Manríquez puts some distance between A-H and such work in “On Anti-Humboldt,” a process note within A-H that divides the book’s Spanish and English versions of the treaty.

There, García Manríquez leads with memory—mentioning twenty-hour bus rides north from Mexico City and a children’s game of “La Migra.” Then, underscoring the paucity of terms in international law to describe Mexico’s current crisis of sovereignty, he situates his project as highlighting “caesura[e] in the language of the law” (72). García Manríquez expounds: “Instead of writing ‘like a poet,’ I am attempting to read like one: creating hollows, pauses, holes, limbos” (74). The distinction, familiar to participants in writing workshops or studio critiques, re-enforces A-H’s contribution to the period’s expanded field of the post/neo/conceptual. Explicitly, García Manríquez leans into a contextured history when he cites as A-H’s “decisive” influence Zong! by M. NourbeSe Philip.9 Like García Manríquez, Philip includes a critical process note with her collection, illuminating Zong!’s material relationship to the 1781 court case Gregson v. Gilbert, which pertained to a captain’s decision to throw overboard his cargo of enslaved peoples. Philip also grayscales Gregson v. Gilbert to practice reading as an audiovisual disinterring of the “cacophony of voices,” literally and figuratively drowned out in legal considerations of the maritime insurance principle of the “general average.”

A-H after Zong! plots an arc of neo/colonial encounter, manifest in García Manríquez’s parsing of his project’s title: “Initially I had planned to contrast [Alexander von] Humboldt’s work with the ‘treason’ that to his oeuvre NAFTA would represent; later I understood that far from being opposed, they can be seen as two complementary moments on the same continuum” (75). García Manríquez cites NAFTA—the text of the treaty and its “total speech situation”—the era it epitomized from the “New World Order” to “Prevention through Deterrence”—in a long line of juridical events (documents and their performative effects), bound up in the biopolitical management of the (human) commodity. “Reading like a poet” between the lines of cultural exemption and the Mexican Exception, García Manríquez models a method of scansion in which the questions “In what ways might the arts illuminate law?” and “In what ways might law illuminate the arts?” cannot be disentangled. Connecting the period’s literary and visual arts, the poet’s clairvoyant practice amplifies genre and medium up to and including the Conceptual -isms of “nation,” “race,” “market,” “border,” and “human.”

Cite this article: Amy Sara Carroll, ““Reading like a Poet” between the Lines of the Cultural Exemption and the Mexican Exception,” in “Beyond Copyright: How does Law Impact Art?” Colloquium, ed. Wendy Katz and Lauren van Haaften-Schick, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17440.

Notes

- Amy Sara Carroll, REMEX: Toward an Art History of the NAFTA Era (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017). ↵

- For more on the “cultural exemption,” see Claire F. Fox, The Fence and the River: Culture and Politics at the U.S.-Mexico Border (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). ↵

- Gareth Williams, The Mexican Exception: Sovereignty, Police, and Democracy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). ↵

- Luis Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007), 3. ↵

- Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Contexturas: Lo global a partir de lo local,” in Horizontes del arte latinoamericano, ed. José Jiménez and Fernando Castro Flórez (Madrid: Editorial Tecnos, 1999), 69–81. ↵

- Hugo García Manríquez, A-H: Anti-Humboldt: A Reading of the North American Free Trade Agreement / A-H: Una lectura del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (Brooklyn; Litmus Press; Mexico City: Editorial Aldus, 2014). ↵

- Cristina Rivera Garza, Los muertos indóciles: Necroescrituras y desapropriación (México: Ensayo Tusquets Editories, 2013). ↵

- Kenneth Goldsmith, “The Body of Michael Brown,” performed at Interrupt 3, Brown University, Providence, RI, March 13, 2015; Vanessa Place, Tragodía 1: Statement of Facts (Los Angeles: Blanc Press, 2010); Vanessa Place and Robert Fitterman, Notes on Conceptualisms (Brooklyn, NY: Ugly Duckling Press, 2009). ↵

- M. NourbeSe Philip, Zong! (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2008). ↵

About the Author(s): Amy Sara Carroll is Associate Professor of Literature and Literary Arts at the University of California, San Diego.