Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919–1939

Curated by: Eckhart J. Gillen and Ulrike Lorenz

Exhibition schedule: Kunsthalle Mannheim, October 12, 2018–February 3, 2019

Exhibition catalogue: Eckhart J. Gillen and Ulrike Lorenz, eds., Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919–1939, exh. cat. Bielefeld/Berlin: Kunsthalle Mannheim is association with Kerber Verlag, 2018. 400 pp.; 196 color illus.; 310 b/w illus. Softcover $26.60 (ISBN: 9783735604583)

Curator Ulrike Lorenz begins his introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919–1939 with the story of the purchase, in 1924, of George Grosz’s View of the Metropolis, 1916–17, by the newly created Kunsthalle Mannheim. Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the forward-thinking director who made the purchase, was self-consciously assembling a collection of socially engaged contemporary art. Hartlaub’s vision for the Kunsthalle Mannheim was for it to be a place for encounters between avant-garde art and society, and the museum, located in the leading German manufacturing city of the Weimer Republic, retained its prominence until the beginning of National Socialism in 1933. In 1937, 571 of its paintings, sculptures, and prints were removed as part of the Nazi purge of degenerate art. Much of the collection, including the Grosz painting—now in the collection of Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and not lent to the exhibition—has never returned to Germany. This is a heart-rending story with which to open the catalogue, and it sets the stage for the almost painful timeliness of the whole exhibition. It also highlights why the newly renovated and expanded Kunsthalle Mannheim was the ideal, and only, venue for this remarkable exhibition.

Ten years after the global financial crises of 2008, the curators argue that “the exhibition Constructing the World presents the dramatic influence of the economy on art in a global comparison for the first time.”1 The curators came to the “surprising observation of a nearly analogue development of the visual arts in the Weimer Republic” and in the similarly federalist-structured United States and Soviet Union between1919 and 1939.2 The exhibition included 225 paintings, photographs, films, and prints from 116 artists from three countries that the curators argue convincingly explored “ideologies of order” in a time of chaos.3 In addition to the exhibition reviewed here, the kunsthalle held a companion exhibition and catalogue, Constructing the World: Art and Economy 2008–2018, curated by Sebastian Baden. These exhibitions of historic and contemporary art made explicit the connections between economics and art in a time of global financial crises, one hundred years ago as well as today.

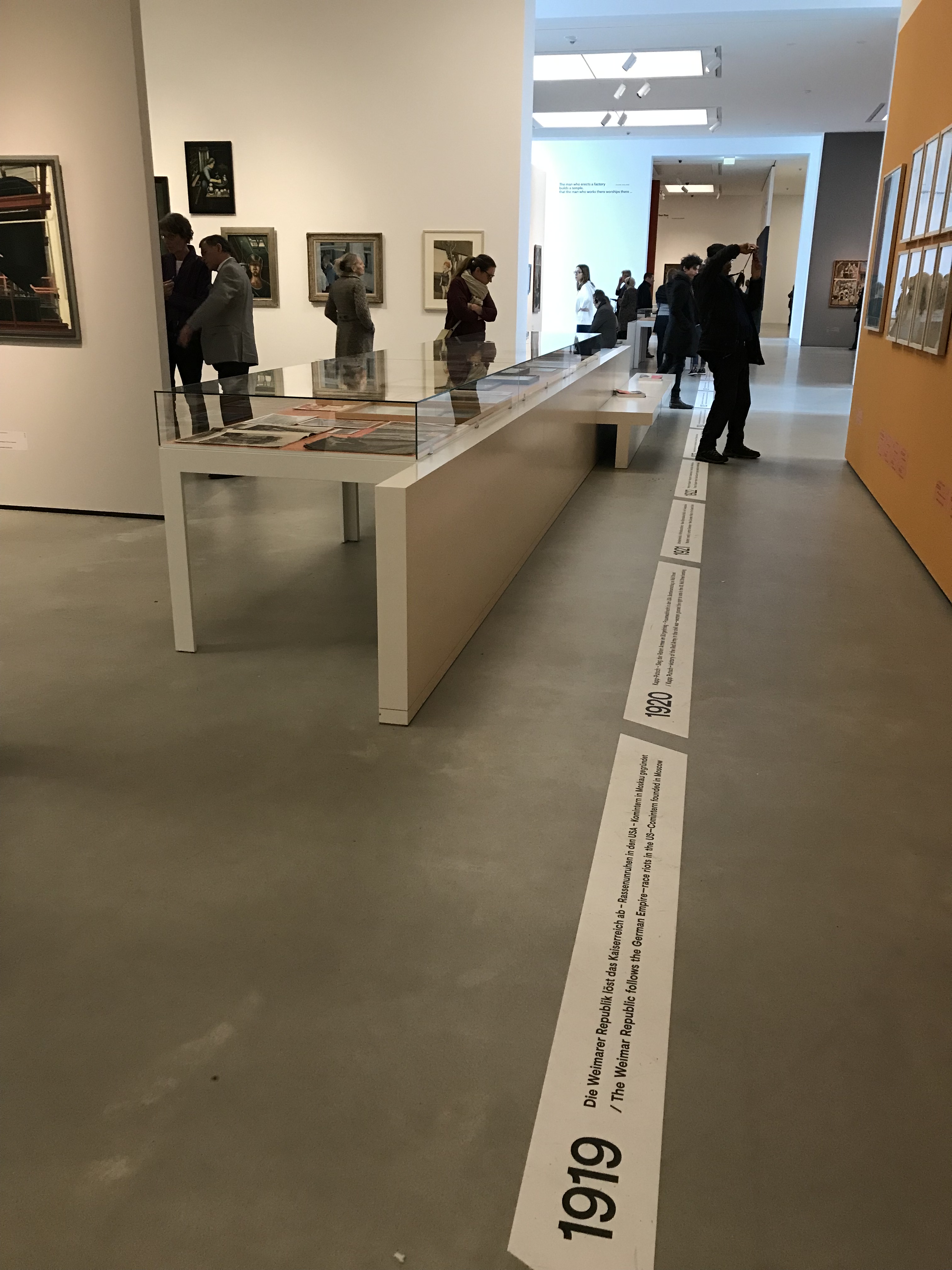

In his essay “Superman in the Turbine Hall: Designs for a New World and a New Man,” curator Eckhart J. Gillen lays out the contemporary stakes of this historic exhibition. “We are currently experiencing a return of authoritarian regimes, right wing populism, an impending trade war with customs duties, and growing xenophobia or even open racism.”4 Indeed, as I walked through the exhibition, I was overwhelmed by the similarities between the time period explored in the exhibition and our own. Artistic parallel movements in all three countries include Neue Sachlichkeit, Precisionism, and the Society of Easel Artists in the 1920s; and Regionalism, Native Art, and Socialist Realism in the 1930s. As Gillen’s essay states: “In the German Empire and the United States National Socialism and the New Deal both began simultaneously in March 1933.”5 This is made crystal clear not only in the catalogue, but also in the exhibition, where the stunning parallels in the artwork was complemented by excellent exhibition design, including a visual timeline in English and German that ran along the floor of the exhibition, highlighting key year-by-year events in the United States, German, and Soviet history of the era (fig. 1).

The two excellent introductory essays by the curators of the exhibition are followed in the catalogue by a large section of beautifully reproduced color plates, aligned with the three exhibition sections. Following the plates there is an extensive twenty-page visual and textual timeline that greatly amplifies and expands on the yearly timeline included in the physical exhibition—this timeline alone makes the catalogue a necessary purchase for any Americanist’s research library. After the timeline, there are essays by seventeen outstanding scholars: Helen Adkins, Elmar Altvater, Makeda Best, Daniel Bulatov, Hiltrud Thomas Flierl, Eckhart Gillen, Larne Abse Gogarty, Hans Günther, Karoline Hille, Lynette Roth, Hans Dieter Schäfer, Ute Schmidt, Bernhard Schulz, Zelfira Tregulova, Faina Balakhovskaya, and Otto Karl Werckmeister. The essays are divided into three thematic sections: Plan Versus Market: On the Political Economy of the Soviet Union and the USA; The Ideal of Objectivity: Human-Machine Symbiosis; and After the Crisis: Regionalism, Native Art, Social Realism. The absence of essays by scholars of American art, with the exception of Makeda Best and Larne Abse Gogarty, is not surprisingly felt most keenly in the analysis of the art of the United States. For example, Gillen’s binary comparison between “conservative Regionalists” and “leftist Social Realists,” as well as his dismissal of the importance of modernists working in the 1930s, is reductive.6 There are numerous excellent American scholars of the 1930s who could have given a more nuanced interpretation of the conflicted politics of American artists in that period. That said, the comparative approach between the three nations and the translations into English of the scholarship of leading German and Russian scholars more than make up for the lack of inclusion of Americanists, whose work is easily accessible for readers of Panorama. Following the essays are short artist biographies and a one-page bibliography.

The exhibition was organized into three sections: Period of Cynical Rationality, Human and Machine, and Returning from the Cold. Color was used to great effect in the exhibition, with rich red, ochre, metallic blue, and creamy white offsetting the saturated and pulsating paintings and machine-age prints and photographs. The use of wall color, vinyl wall quotes, film, timeline and interpretive panels was very helpful and not at all distracting from the power of the artwork. The exhibition began with a series of paintings and films depicting the chaos of World War I and the modern metropolis, which sets up Cynical Rationality, the first section of the exhibition. Edward Hopper’s Apartment Houses (fig. 2) is included in this section, although it could as easily have been included in the following section, Human and Machine, with Ekaterina Zernova’s Fish Canning Factory (fig. 3), as both feature women laborers. Hopper’s painting includes his trademark sense of isolation and dislocation due to the solitary woman working, cut off by architecture, while at the same time cramped in the spaces of New York City. In Zernova’s painting, by contrast, the female worker in the foreground is part of a group of women workers, and she is an idealized embodiment of the empowered Soviet worker. The cool detachment and alienation of Hopper’s work might have appeared in German paintings of the period, but not in the Soviet state-sponsored artwork that glorified the proletariat. Also, in the section Human and Machine, paintings by Carl Grossberg and Ralston Crawford speak to machine-age aestheticism, and the cult of industry, of both Germany and the United States in the 1930s (fig. 4). Werner Peiner’s Fieldwork (1931; Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf) and Grant Wood’s Fall Plowing (1931; Deere and Company), both painted in 1930 and included in the section Returning from the Cold, look to farmland as an idealized source of national identity. Peiner uses tempera on wood in an archaizing technique that is reminiscent of Northern Renaissance landscapes, and his figures could be straight out of a medieval manuscript depicting autumn labors. Wood’s canvas is devoid of people; the plow in the foreground takes on a ghostly presence, as it seems to stand in for the absent farmer; and it seems an odd/prescient choice for the John Deere company, a United States corporation whose tractors would make hand plows a thing of the past for most US farmers.

The exhibition ends with a series of devastating paintings by United States and German artists, including Joe Jones’s American Justice (1933; Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio); Alice Neel’s Nazis Murder Jews (1936; Venice and Rennie Collection, Vancouver); and Rudolf Schlicter’s Blind Power (fig. 5). Blind Power is a horrific painting that shows a helmeted and therefore anonymous Roman centurion whose body is made up of creatures that would give Hieronymus Bosch nightmares and would do Ivan Albright proud, holding implements of war and architecture in his hands in front of a burning apocalyptic landscape. Schlicter’s painting is clearly an indictment of German militarism, but the inclusion of the American works in close proximity—namely, Neel’s painting of a protest in the United States that clearly articulates the national policy of isolationism despite awareness of what was happening to Jews under Nazi rule, and Jones’s brutal rendering white hooded hordes of Klu Klux Klan members lynching and burning African American bodies and homes—reminds exhibition visitors of the home soil horrors of the 1930s that the United States has yet to recognize and reconcile.

One of my questions upon leaving this phenomenal exhibition was why it was not traveling to the United States, or indeed Russia. With multiple loans from institutions such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, and the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, those institutions would have seemed the perfect venues for this engrossing and field changing exhibition. The curators made clear that in the period from 1919 to 1939, “Germany as a midsized power between socialist utopianism and imperialist pragmatism” was a perfect foil to the communist and capitalist extremism of the USSR and the United States.7 That Germany retains this position today—somewhere between the extremes of these two post-Cold War superpowers—is telling, and probably leads to the answer to the question as to why the exhibition was only held in Mannheim. When I raised this issue at a conference, sponsored by the Terra Foundation for American Art, on transnational American art in Germany at the University of Mainz a few days after visiting the exhibition, one of the scholars who worked on the Mannheim exhibition explained to me that while the United States and Russia would both lend work to Germany, neither would lend work to each other. Therefore, the realpolitik of global geopolitics shapes our current art world today as much as it did one hundred years ago.

Cite this article: Anna O. Marley, review of Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919–1939, Kunsthalle Mannheim, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2213.

PDF: Marley review of Constructing the World

Notes

- Ulrike Lorenz, “‘Constructing the World’ in the ‘City of Work and Art’: A Programmatic Exhibition for the New Kunsthalle Mannheim,” in Eckhart J. Gillen and Ulrike Lorenz, eds., Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919–1939, exh. cat. (Bielefeld/Berlin: Kunsthalle Mannheim is association with Kerber Verlag, 2018), 16. ↵

- Lorenz, “Constructing the World,” in Gillen and Lorenz, Constructing the World, 17. ↵

- Lorenz, “Constructing the World,” 17. ↵

- Eckhart J. Gillen, “Superman in the Turbine Hall: Designs for a New World and a New Man,” in Gillen and Lorenz, Constructing the World, 18. ↵

- Gillen, “Superman in the Turbine Hall,” 18. ↵

- Gillen, “Superman in the Turbine Hall,” 27. ↵

- Lorenz, “Constructing the World,” 17. ↵

About the Author(s): Anna O. Marley is Curator of Historical American Art and Director of the Center for the Study of the American Artist at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts