Teaching and Creating Art in the Borderlands: A Conversation with Santa C. Barraza

A native of Kingsville, Texas, Santa Contreras Barraza is a contemporary Chicana/Tejana artist and founder of Barraza Fine Art, a gallery and studio committed to showcasing talent and furthering the appreciation of the arts in the borderlands and among isolated, rural populations.1 She formerly taught at Texas A&M University in Kingsville, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Pennsylvania State University, and La Roche College in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She received her bachelor of fine arts in 1975 and her master of fine arts in 1982 from the University of Texas at Austin. Santa Barraza was also a member and cofounder of two pivotal Chicano art collectives: Los Quemados and Mujeres Artistas del Suroeste (MAS).

Taking Nepantla, a mythic “land-between,” as a recurring theme, Barraza’s work “depicts the historical, emotional, and spiritual land between Mexico and Texas, between the real and the celestial, and between present reality and the mythic world of the ancient Aztecs and Mayas.” Her practice draws upon preconquest symbols, personal memories, and traditional sacred art forms in order to show “how Mexican artistic traditions have the power to nurture and sustain cultural identities on this side of the border.”2

As a scholar with expertise in Chicanx art history and theories of the borderlands, this author was invited by the guest editors of this In the Round, Liz Kim and Amy Von Lintel, to speak with Santa Barraza about the intersections between her practices as an art professor and an artist.

Mary M. Thomas (MT): Can you tell me about the relationship between your identities as a professor and as an artist, and what that relationship has been like throughout your career?

Santa C. Barraza (SB): When I secured my first position in higher education, it was [at La Roche College] in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; it’s a small private Catholic college. They had no understanding of what a Chicana was, so I identified myself as Mexican American. Once I left that small college, I went to Penn State University, and since it’s a more affluent institution of higher learning with international students and national students, I felt like I could say I was a Chicana. As an artist, I always was a Chicana, but as an educator, I was first at La Roche College a Mexican American and then later Chicana. I think that you could say in a way that my background was like what Gloria Anzaldúa calls Nepantla, which is a state of two cultures colliding, recontextualizing, and a third one emerging. I felt that way throughout my career . . . and so it was sort of like this new hybrid culture, a new hybrid existence, and living in two cultures, and understanding both, and moving from one to another, as Gloria Anzaldúa stated.

MT: When you’re in the classroom, how does your work as an artist inform how you teach?

SB: When I taught at Penn State, we were advised not to show our work to the students. They advised us to be careful because the students would copy us so they could get a good grade. I used to show the students my work, but I would try not to do it too often because I didn’t want them to be influenced by what I was doing. In Kingsville, at Texas A&M University, I would take students to exhibitions that had my work in it, and they would see that they could accomplish that, too. I thought that was more important than to actually show them my work, but I would bring some of my original pieces and other artists’ artworks into the classroom and show them techniques, such as mixed-media techniques. I would show them how it was possible to utilize them onto paper, canvas, or with certain media as unique materials. In Kingsville, the students are very economically deprived. Some of them have never left South Texas. That’s why it was very important that I travel, set up study abroad programs, and take them with me, because this was an opportunity for them that they might never have.

MT: Can you tell me about your experience of traveling to Oaxaca and developing a study abroad program there?

SB: As a recipient of the Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest grant in 1993, I was a resident artist in Oaxaca. I really liked Oaxaca. I spent several months there. I met many artists, such as Francisco Toledo and Roberto Morales and the young artists. I learned about the schools and their different styles: there’s the school of Tamayitos, Rufino Tamayo’s students, and the Toleditos, Toledo’s students. Oaxaca was unique because there you have the Mixtec and the Zapotec cultures, and Monte Albán. That’s where I started using papel amate, which is bark paper. The artists there use papel amate in everything. I learned how to prepare the paper from the visual artists.

When I was hired by Texas A&M University at Kingsville [as a professor in 1997], I developed a study abroad program in Oaxaca because I knew many people there. The university set up an agreement with the Benito Juarez School of Visual Arts for our students. The students studied in their facilities, and I taught the classes. We also recruited students from Benito Juarez School of Visual Arts to come to Kingsville for a summer program and to pursue an undergraduate degree here. I also developed a similar study abroad program at the University of Graz in Austria.

MT: I’m really struck by the fact that you’ve been committed to a project of building something that extends beyond the physical spaces of the classroom and university—and that even transcends national borders. This commitment has spanned your entire career. Can you talk about your experience as a member of Los Quemados and a cofounder of Mujeres Artistas del Suroeste (MAS) during the 1970s?

SB: MAS was cofounded by Nora Gonzalez Dodson and me in 1975 and was active for a decade.3 We met as undergraduate art students at UT Austin, and we both worked in the same company, Steck-Vaughn Publishing Company. During lunchtime, we would converse about art. One of the issues that came up was the lack of female membership in the Los Quemados art group.4 There were very few women in Los Quemados. It included Carolina Flores from San Antonio, Carmen Lomas Garza, myself, and the rest were men. I kept telling them⎯this is when the feminist movement was emerging⎯“I think we need to form our own groups because we need to self-identify ourselves. We need to support each other.” We all had art classes with only Euro-American male professors, and we recognized that we needed to have the support of women.

As MAS, we had a studio on Sixth Street in downtown Austin. We would paint and work together and critique each other’s work. We started venturing out of Austin, exhibiting into San Antonio and Phoenix, Arizona.5 We also had the opportunity to put together some programming⎯that became very important to us. For example, Sylvia [Orozco, MAS member and cofounder of Mexic-Arte Museum] left Austin and went to study for her masters in San Carlos Academy of Art in Mexico City. When we as MAS put together the Conferencia Plástica Chicana in 1979,6 we affiliated ourselves with Sylvia because we wanted to bring artists from Mexico to be part of the conference. She helped us get some of those artists to participate, but she also brought us twenty-five students from the San Carlos Academy of Art to come to the conference.

We also invited art critic Raquel Tibol, who was the personal secretary of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Adolfo Mexiac, who was one of the Taller de Gráfica Popular artists, was one of the invited artists, as well as Chicano/a artists and scholars. We brought in an exhibition of photographs by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, the father of Mexican photography, at the Texas Memorial Museum.

MT: To put the formation of groups like Los Quemados and MAS in context, this is the time when Chicanos were creating their own institutions and thinking about what needs weren’t being met in existing institutions and building something outside of those spaces that responded directly to not only the community’s needs but also to the future that they wanted to see and wanted to have. Could you talk a little bit about what led up to that moment, from your vantage point as a student and an artist at that time?

SB: The Civil Rights Movement here in Kingsville was very active.7 When I was an undergraduate at Texas A&I,8 Carmen Lomas Garza and Amado Peña were students there, too. Carmen was, I think, already a junior or senior when I was an incoming undergraduate. She could have been a junior, I don’t recall, and Amado was a graduate student. Another student was José Rivera, who was getting ready to graduate with his art education degree. Carlos Guerra was here founding MAYO (Mexican American Youth Organization). Amado Peña and Carmen Lomas Garza were the stars of the art department. They would have these happenings in the art gallery. Carmen would wear these paper dresses in the art gallery. It was like a happening, and they had paper hanging from the ceiling, and music and blacklights in the gallery. She would come in dancing through the paper, and the paper would move like magic. I was so in awe of everything that was going on. There was a lot of activity and protest but, since they were older and I was the rookie, they were more involved.

Amado Peña was doing this wonderful series of silkscreens of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. He did a lot of political images in that graphic style of serigraphs. He does not work with those images or style anymore. But that’s what he was doing when he was a graduate student here⎯very political⎯so I was very much inspired by the work of these other students. Carmen Lomas Garza had organized a show in Mission, Texas, I think. It was held at a cultural center affiliated with Jacinto-Treviño College. There was much activism here in Kingsville, so that really influenced me. When I transferred to UT Austin [after three semesters at Texas A&I], there was another group of students, doing the same thing there.

At UT Austin, I started really developing my artistic sensibility, because we had so many more scholarly resources there, like the Benson Latin American Collection. You could go there, and you could research all these things on Mexico. One of the things that we would talk about was the Red Baron of the Rio Grande. His actual name was Juan Nepomuceno Cortina, and he was caught in between the two cultures because his land was partly in Mexico and partly in the United States in South Texas [after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo of 1848]. He had to fight to keep his land, and they labeled him and identified him as a thief, but he was just trying to collect his cattle and reclaim his land. I remember my mother referring to him as Cheno. I did paintings of Cortina, and paintings of Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. We would retrieve Casasola photographs, so I did drawings based on some of Casasola’s photographs of the Adelitas, of Zapata, and Villa (fig. 1).

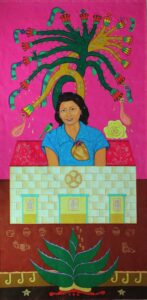

MT: Hearing you speak about the significance of the source material that you’ve drawn upon makes me think about your work and your ability to bring in imagery from Mesoamerican culture and recontextualize it. You bring this imagery to life through your use of color, because we often see the images as inscriptions on stone or black-and-white illustrations. Similarly, in historical photographs, like the Casasola photographs, the historical details often feel very remote, but you bring them forward and integrate them across historical eras. This is especially apparent in your Mujeres Nobles series, in works such as Frances con el Arbol de la Vida, which features your mother (fig. 2). Can you tell me how you approach working with such a rich array of source material?

SB: My graduate work was based on shamanism and curanderismo (folk healing), and how they are related to each other. I became very interested in materials. When I went to Oaxaca, I saw that the artists work on amate paper, which is a bark paper. It used to be a sacred paper in ancient Mexico. The Aztecs would force all of the tribes around them, especially in the San Andres area, which is where they make the paper, to pay tribute to them with it. At the end of the year, they had to deliver so many tons of that paper because they would cut effigies, and they would burn them as offerings to the gods because it was a sacred paper.

I was impressed with the idea that this is a sacred paper, so I started using formats that were Mexican and ancient but in a contemporary way. Where you see my mother, Frances con el Arbol de la Vida, the painting is on amate paper. It’s four feet by eight feet. My mother died in 1992, and so I started painting about my mother in different mediums and formats. Even before she died, I produced retablos and canvas paintings of her because she was a very strong person. I really admire that, and so I started creating artwork about her and other women that I admired.

I appropriate and mix everything up into one format. I take from the Mixtec, Axtec, Zapotec, Olmec, and Maya. I just appropriate like postmodernism, appropriate from everything and then sort of make it my own.

MT: Thinking about the trajectory of your career, there’s a recurring theme of being in an environment where you’re in close conversation with other artists and able to see how they’re thinking about their practice and working with materials. [In 1986], you received a fellowship and attended a residency at the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop and met a number of artists. What was that like?

SB: It was just for the summer program, but I met so many national and international artists. I don’t know if you’re aware, but in India, a member of parliament was a visual artist, and so I met him at Bob Blackburn’s workshop. I met Faith Ringgold, Candida Alvarez, and her husband, Dawoud Bey. Of course, we were just struggling artists at that time, and we did projects together. On Monday nights those of us with fellowships would study printmaking because we were painters, we really weren’t printmakers.

I learned a lot of techniques from that class but also from other artists. One of the other artists I met was Juan Bosa, who was originally from Cuba. He was doing these beautiful prints in a circle. He was a Santero, and he would take Formica⎯they would sell it there in New York City, four feet by eight feet. You could buy one from the plastic shop, and it was like $8 or $10 for a sheet that you cut to the size and shape that you wanted with a pair of scissors or an exacto knife. He would get huge circles, and then he would get sticks and leaves and all kinds of found objects, and he would put them on there, and he would ink it and make these beautiful collagraph prints. I learned how to do that from Juan Bosa.

MT: Are there any works from that time that were your favorites?

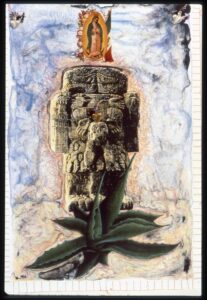

SB: My favorite was a stone lithograph of Coatlicue, the earth goddess, that I did as a transfer from a Xerox onto the stone, with Bob Blackburn helping me (fig. 3). As a printmaker, you do artist’s proofs to see how the stone is holding up and what it’s doing, especially when you do a water tusche and other techniques. I did proofs of the Coatlicue transfer, and they came out beautiful. I said, “Okay, it’s fine, so let me do other stuff.” So, I did other things to it: I collaged onto them, and I stitched little milagros [votives] on them. Bob Blackburn wanted to include some of my prints in a biennial exhibition in Europe that he organized, but when he saw what I had done to the prints, he told me that it wasn’t an edition anymore [laughs]. Unfortunately my prints were not included in the exhibition.

MT: I’m also interested in talking with you about your participation in the Nepantla Taller with Gloria Anzaldúa. It was another environment where you worked really closely with other artists and other writers in an immersive environment.

SB: I have to tell you a little bit of the history of that project, because Gloria and I go back to UT Austin. When I lived in Austin, I had a gallery in East Austin. I founded it in 1980, and it was active until I left Austin in 1985. Gloria came to visit my gallery, and we became friends.

Later on when I taught at Penn State University, Gloria was a guest speaker there. At that time, she told me that she was thinking of doing this project on Nepantla. It was going to have two components: writers and visual artists. We were housed in the [Villa Montalvo Artist] residency in Saratoga, California. The participating visual artists were Liliana Wilson from Austin, and Christina Luna, from Mexico City, and myself. So it was just Gloria and Isabel Juárez Espinosa from Chiapas, who was the other writer. I had a little cottage with a studio. Liliana and Tina were in a big house with Gloria, and Isabel had a little cottage, too. Every night, we would have dinner together, and then we would discuss what we were doing and the concepts and what [Gloria] thought and what we thought, and we would negotiate and converse back and forth.

One of the things that [Gloria] said about her concept of Nepantla is that she felt that this millennium was the millennium of Coyolxauqui, the moon goddess. She was going to take back what had been lost from her, because the earth actually is female, and everything became patriarchal, so we’re going to become matriarchal again. Coyolxuaqui was going to take back her power, and the new millennium was going to be that millennium. She was a very strong believer in that. She would show us drawings that she had done. She studied art, and she really loved art. She had drawings of Coyolxauqui and the body parts, and she had all these symbols regarding Coyolxauqui that she would show to us, and then we would talk about our reactions to it and our feelings. Everybody had their own projects, so we did our own artwork, and then the writers did their own writing.

MT: What did you create during the residency?

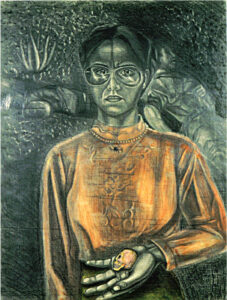

SB: I produced several large pieces of artwork, including Teotl, a large charcoal drawing on canvas, and Mujeres de Nepantla, a large oil painting (fig. 4).9 I also did a retablo painting project with children of homeless families.

At the end, even Liliana had to help me finish (Mujeres de Nepantla) because I couldn’t finish it. I also sought out a shelter for the homeless in San Jose, and I taught retablo painting to children there. When I approached the center, they asked how long the project was going to take, and I told them it was going to take me at least seven to ten days to do it. They said that these kids come and go, so I wouldn’t have the whole ten days to work with them, and I said that’s okay, we’ll work with what we have. They didn’t think it could be done. The project was for the children to paint a miracle in their lives. They made beautiful work⎯they even did the frames for the pieces. Their mothers and fathers were so impressed that they also became involved in the project with the children, so we had their work as part of the exhibition at the finale of the Nepantla project.

MT: In speaking with you, I’m moved to think about the relationship between storytelling and spirituality, and how they’re intertwined in your practice. What are the stories that you find most important to share through your practice and in your teaching?

SB: I was told that I couldn’t get a PhD in Chicano art history because it didn’t exist. It was sort of like telling me that I’m not a valid person, that I don’t have validity, I don’t really belong here, that kind of connotation. I felt that it was important to validate myself and self-identify myself. I went to the library, and there was nothing about the Mexican American experience. That’s why I looked for Casasola. I looked at some of the photographs of Russell Lee, who was one of our professors at UT Austin. He was a WPA (Works Progress Administration) photographer.10 I did a drawing of migrants from one of his photographs of migrants in a camp, the tent cities that they had in California when they brought the workers from Mexico during World War II. I started looking into my own family because my mother had all these stories, you know, from the family (fig. 5). One of the stories that she would always talk to us about was from the Bible. I started looking at ancient Mexico. The Bible, of course, has a story of Adam and Eve, right? But the Popol Vuh is also about the creation of humanity. So, I found correlations. I tell my students that all of these things in our culture [are characterized] as folklore. It’s not really folklore—it’s very ancient, so they have a very ancient heritage, I tell them: “You’re very valid, so you need to learn this history so you can validate your art because when you defend your art, you’re defending yourself.”

When I was a grad student, I was making three-dimensional fiberglass murals. One of the members of my committee told me that the committee did not like what I was doing and that muralism is not art because it was not [individually produced] art, it’s collective art. Originally [my MFA project] was a mural for a public library. They told me to scrap that project because if I didn’t, I wasn’t going to graduate.

Thereafter, I started working on the shamanism concept instead, with dreams, because that’s part of the initiation process of the shaman and a direct correlation to curanderismo (fig. 6). My sister was sick at that time, and so it really helped me also deal with my sister’s illness. I received [my MFA] in studio art, but when I was teaching at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, UT San Antonio contacted me to hire me as a consultant for public art at a new biosciences building. Eventually, the committee told me that they wanted to hire me as a partner with Alice Adams to do two murals for this building. One was a rotunda mural, and the other is a retablo mural painted on metal on a curved wall. The irony is that [my committee at UT Austin] told me that my art was not valid, then years later, they hire me to do murals for them. I tell the students this story because I tell them to do what they feel is important to them.

Cite this article: Mary Thomas, “Teaching and Creating Art in the Borderlands: A Conversation with Santa C. Barraza,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12627.

PDF: Thomas, Teaching and Creating Art in the Borderlands

Notes

- “About Santa Barraza,” Santa Barraza, accessed July 31, 2021, https://www.santabarraza.com/about-me. ↵

- Maria Herrera-Sobek, ed., Santa Barraza: Artist of the Borderlands (Kingsville: Texas A&M University Press, 2000), flap copy. ↵

- Shifra M. Goldman, “Women Artists of Texas : MAS = More Artists Women = MAS,” Chismearte 7 (January 1981): 21–22; “Documents of Latin American and Latino Art,” International Center for the Arts of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, accessed July 31, 2021, https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/847000#?c=&m=&s=&cv=-4&xywh=-791%2C602%2C3433%2C2291. ↵

- Brochure for Artistas Chicanos: Los Quemados, June 20 through July 13, 1975, Mexican Cultural Institute, San Antonio, TX, reproduced in “Documents of Latin American and Latino Art,” https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/847390#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-1198%2C0%2C4944%2C3299. ↵

- For more information on the history of MAS, see Santa Barraza, interviewed by Cary Cordova for Oral History interview, November 21–22, 2003, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 20–27, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-santa-barraza-13254#transcript; Santa C. Barraza, “An Autobiography,” in Herrera-Sobek, Santa Barraza, 38–39; and Shifra M. Goldman, “When the Earth(ly) Saints Come Marching In: The Life and Art of Santa Barraza,” in Herrera-Sobek, Santa Barraza, 55–56. ↵

- See brochure for Conferencia plástica chicana, September 13–16, 1979, Centro Cultural de Lucha, Austin, TX; reproduced in “Documents of Latin American and Latino Art,” https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/849438#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=575%2C797%2C857%2C497. ↵

- For more on the artist’s relationship with the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, see Santa Barraza, interview transcript, 13–17; Barraza, “An Autobiography,” 35; and Goldman, “When the Earth(ly) Saints,” 55. ↵

- Editors’ note: The Texas College of Art and Industries (Texas A&I) became part of Texas A&M in 1989 and changed its name to Texas A&M University–Kingsville in 1993. ↵

- For more on the works created during the Nepantla Taller, see Barraza, “An Autobiography,” 6–11. ↵

- Lee worked on federal projects, but not under the WPA; he was a photographer for the Resettlement Administration, later the Farm Security Administration and, later, the Office of War Information. ↵

About the Author(s): Mary Thomas is an Independent Scholar