Critical Cataloging, or Why Collection Descriptions Should Be Reviewed

PDF: de Vletter, Critical Cataloging

The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal has been collecting ideas on architecture since 1979, with the goal of building a helpful resource for researchers worldwide. All material that enters the CCA collection is recorded: books, periodicals, toys, and miniatures are cataloged in a library database; photography, prints, and drawings are recorded in an object management system; and archival holdings are described in finding aids.1 Descriptions are created to identify objects or groups of materials, to manage and track materials, and ultimately to make them accessible for research.

Descriptions are produced when objects enter the collection, and they tend to become permanent, unchanged even when new research on the objects becomes available.2 For areas of knowledge with terms that evolve rapidly (such as in studies related to gender), cataloging processes cannot constantly adapt, as it would simply require too much research. Collection descriptions are therefore themselves historical records.

Realizing over time that some of these records are incomplete and inaccurate, especially when images are attached to the record and visible online, the CCA’s critical-cataloging project started in September 2020 to review the object descriptions then in use.3 Critical cataloging incorporates inclusive description and metadata strategies to improve discoverability.4 The project began by identifying the most harmful language used in records across the CCA collection—including words like “slave,” “indian,” “albino,” and “servant”—and we have now started to revise constructed titles in records of the photography collection. The words and terminology that we look for are defined by various lists shared among librarians and archivists, such as the Harmful Description Lexicon created by Princeton University.5 In order to be transparent, we update our webpage on the project regularly.6

We started by creating a list of harmful language pertaining to our collection. Words in the titles like those mentioned above (constructed, inscribed, or artists’ titles) were reviewed case by case, and a new description was added to the database—the original was not erased. A second, more complicated phase was then implemented to identify problematic concepts and absences in necessary information. Not having a description at all can be as problematic as harmful language, because it means researchers will not find a work based on their search on our website, giving the impression that the work was not considered worthy of a description. Merit or importance, however, is not a factor in the presence of description; it could be missing simply due to a lack of time, resources, or expertise at the time the object entered the collection.

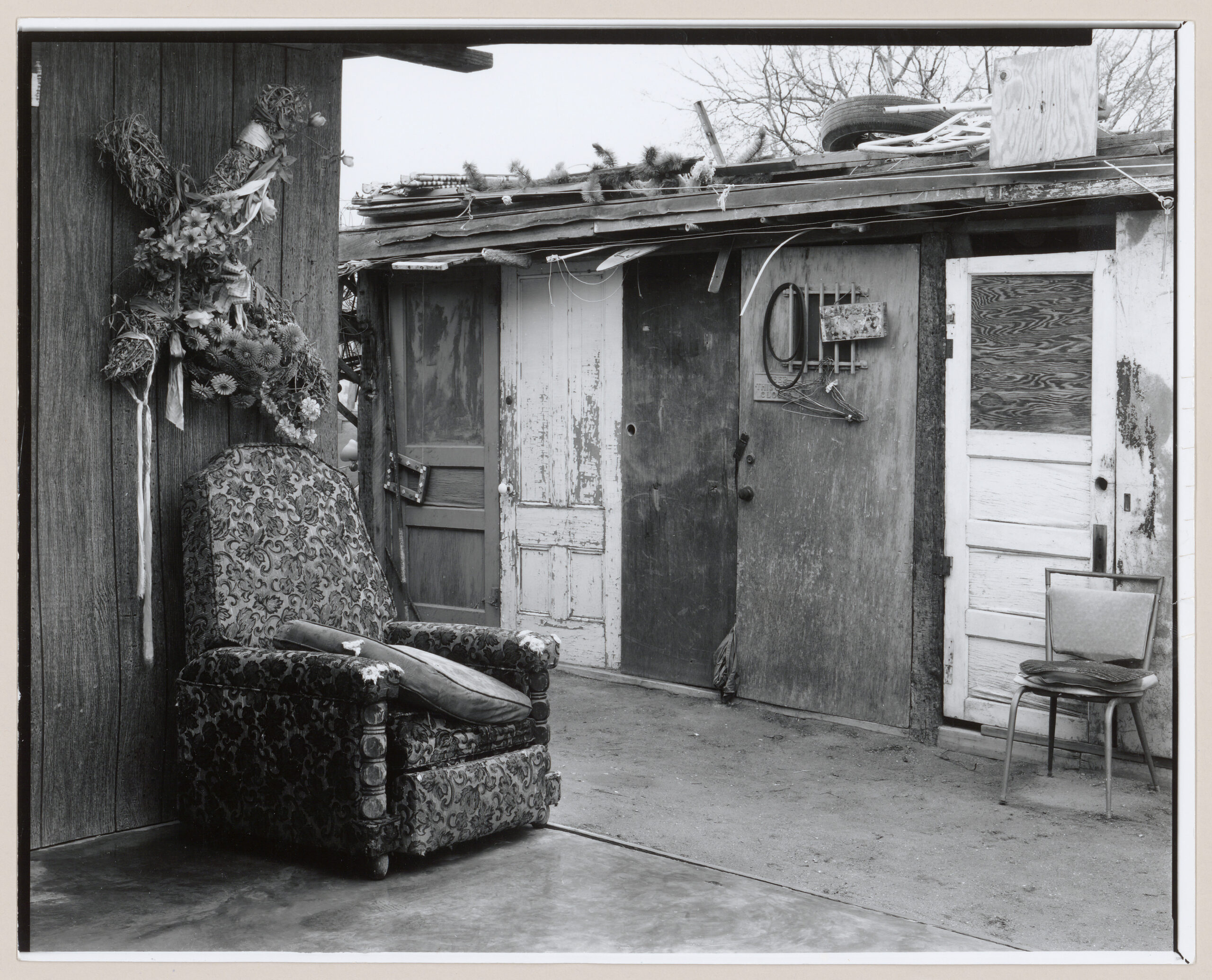

Former constructed title: Partial view of a covered patio [?] with a cross decorated with artificial flowers affixed to a wall of a house on the left and a cabin, Old Pascua, Tucson, Arizona.

Current constructed title: View of cross decorated with flowers hung above upholstered chair in outdoor space, Old Pascua, Tucson, Arizona, United States (from a series documenting the Yaqui community of Old Pascua).

Current added description: One of a series of forty-four photographs of the Yaqui community of Old Pascua by Lorne Greenberg. The photographs document the relationship between household and church in the Yaqui community. The photographs were exhibited at the Arizona State Museum in 1983. The CCA collection includes ten photographs from the series (PH1989:0147–PH1989:0156). In 1978, the San Ignacio Yaqui Council applied for Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), which had been established by the United States Government in 1974. The community first received CDBG funding in 1979/1980. Since that time, most of the owner-occupied houses in Pascua Village have been torn down and new homes have been built.

This work on interpretation (traditionally the domain of the researcher) is different from the technical practice of cataloging (traditionally the domain of the cataloger or archivist), in which language is standardized to ensure consistent terminology for multiple records. However, today the interpretive work accompanies the cataloging, and we decided early on that the goal should be to improve access in order to stimulate research. This objective raises questions in itself. Should we allow for images online that can hurt marginalized communities? If so, how can we navigate between increasing discoverability on the one hand and potentially hurtful images on the other?

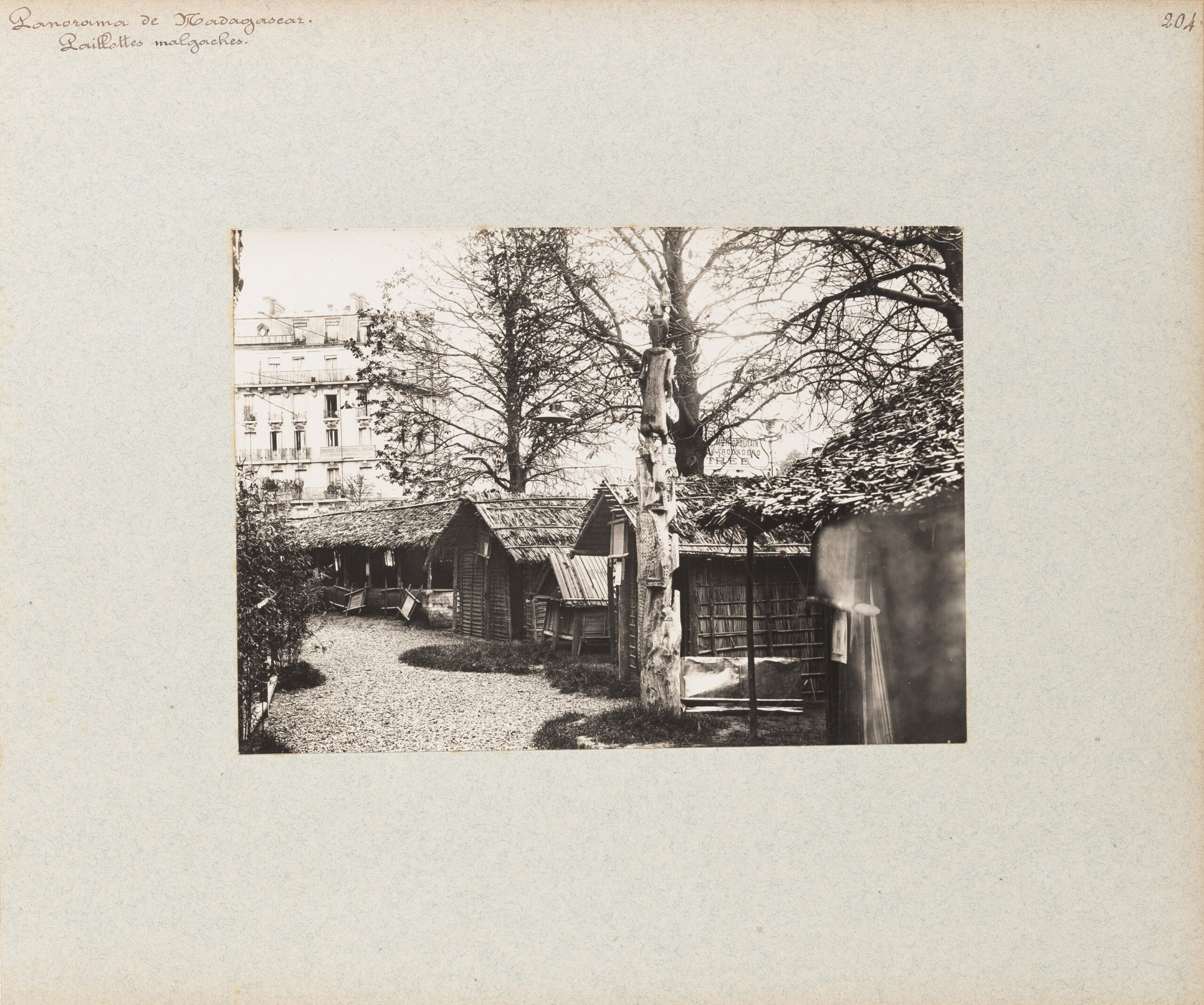

Former constructed title: none. The image has an inscribed title, which was displaying in the database: Panorama de Madagascar. Paillottes malgaches.

Current constructed title: View of Malagasy houses with thatched roofs on grounds of Pavillon de Madagascar, Exposition universelle, 1900, Paris, France.

Current added description: According to Paul Gers, these structures were transported to the exhibition from Madagascar. Malagasy people who had been brought to Paris to be part of the exhibition at the Pavillon de Madagascar lived and worked in these structures during the day.

We established a dedicated Critical Cataloging Work Group consisting of CCA staff.7 Over time, the intensity of the work has fluctuated. A reading club was established to allow for periods when the describing work would pause so that the group could focus on reading and discussing. The process of assessing individual records still progresses at a modest speed, but the work group has gained considerable experience in constructing appropriate and respectful terminology and titles, identifying locations or constituents, and evaluating the (historical) context of the depicted persons and scenes. Since 2020, the work group has reviewed roughly one thousand records related to architectural terms and buildings, such as “plantation,” “reserves,” “pueblo,” “arab,” and “mosque/masjid/madrassa.” After all, the CCA is about architecture. Records with images online were prioritized, as they attract more attention from our scholars.

Former constructed title: Workers’ shacks, Hosiery Mill, Rome, Georgia, United States.

Current constructed title: View of wooden building typically occupied by workers from Rome Hosiery Mill, Rome, Georgia, United States.

Current added description: Photograph taken while Lewis Wickes Hine was working for the National Child Labor Committee. Caption from NCLC caption card: “Some of the workers in the Rome (Ga) Ho[s]iery Mill live in shacks like these.”

Sometimes groups of photographs were intentionally reviewed and descriptions revised. Other times we stumbled on material by chance or circumstance. For example, we reviewed the recontextualized series by Lorne Greenberg (Canadian, b. 1948) on the Yaqui in Old Pascua, Arizona, photographed before the redevelopment of this Indigenous community (fig. 1).8 The constructed title was appraised, and a description was added (there was none) that contextualizes the photographs and the circumstances depicted. For another example, the cataloging of an album on the Exposition universelle of 1900 was altered to include appropriate terminology for Indigenous houses from former French colonies like Madagascar (fig. 2). We also were able to identify the photographer of the album, Paul Gers (French, 1857–1942),9 which is important since the CCA seems to be the holder of the sole copy of this album. Initially there was a very minimal description for the album, but none for any of the individual photographs in the album. In a third example, descriptions for seventeen photographs by Lewis Wickes Hine (American, 1874–1940) related to child labor were revised and augmented (fig. 3).10 This project became an occasion for the work group to discuss gender-specific vocabulary and whether it is appropriate to use terms like “boy” or “girl” to refer to children whose names (and sometimes genders) are unknown to the cataloger.11 This reevaluation inspired us to adopt more neutral descriptions in regard to the gender of the children.

Initially we thought about establishing standards for revising descriptions, but the consensus now is that decisions need to be made on a case-by-case basis. Descriptions are contextual, and it is important to recognize their historical and current context. This is also reflected in a series of articles published on the CCA website on the value of interpretation in combination with the technical practice of cataloging, by both CCA staff and external researchers.12 These reflections are helping the CCA create meaningful and inclusive descriptions to increase the discoverability of histories, narratives, and contexts that would otherwise not appear in object records.

Cite this article: Martien de Vletter, “Critical Cataloging, or Why Collection Descriptions Should Be Reviewed,” in “Critical Cataloging: Researching American Art History on Its Own Terms,” ed. Tracy Stuber and Jennifer Way, Digital Dialogues, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19825.

Notes

I want to thank and acknowledge the team involved in the work of critical cataloging: the core team in 2024 with Hester Keijser, Jennifer Prefontaine, Caroline Dagbert, and Mary Gordon as well as Christine Lefrancq, Céline Perreira, Shukri Sultan, Emma Martin, Leonie Hartung, Emma Rath, Ella Esslinger, and Keamogetse Mosienyane.

- Since 1999, materials in the library collection were cataloged in the library database Horizon. The CCA recently moved these records to a new platform, WMS, while photographs, prints, and drawings are described in TMS. Archival data has been moved to an archival management system called ArchiveSpace. These databases “feed” CCA’s online-access interface, which is hosted through the CCA website. ↵

- Description practices for library material are historically more structured and standardized than description practices for museum objects, such as photographs, prints, and drawings. Archival description practices are different altogether. Only recently have archival description practices been updated to rectify injustice and exclusion, for example, by the Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia’s Anti-Racist Description Workgroup of October 2019 (https://archivesforblacklives.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ardr_final.pdf). The CCA has been working on a Finding Aid Audit, funded by a grant from Library and Archives Canada (LAC), to identify descriptions that require revision. ↵

- The pandemic allowed us to accelerate this process, with staff working from home and not always able to do their regular work. ↵

- The terms “critical cataloging,” “ethical cataloging,” “radical cataloging,” and “conscious cataloging” have been used interchangeably to describe the same idea. ↵

- This list is basically a google document, available upon request. ↵

- “Critical Cataloging and Reparative Descriptions,” CCA, accessed May 22, 2025, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/82982/critical-cataloging-and-reparative-descriptions. ↵

- The working group consists of catalogers, the curator, photography and new media, curatorial interns, reference librarians, and others that want to join, even just occasionally. ↵

- See the CCA search results page for Lorne Greenberg: https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/search?query=Lorne%20Greenberg&filters=%7B%22forms_collection_library_bookstore%22%3A%5B%22photographs%22%5D%7D ↵

- See the CCA search results page for Lorne Greenberg: https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/search?query=Lorne%20Greenberg&filters=%7B%22forms_collection_library_bookstore%22%3A%5B%22photographs%22%5D%7D ↵

- See the CCA search results page for Lewis Wickes Hine: https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/search?query=lewis%20wickes&filters=%7B%22forms_collection_library_bookstore%22%3A%5B%22photographs%22%5D%7D ↵

- In our current website, unfortunately, are not able to show more than one description or title, which means the history of constructed titles or descriptions that would show evidence of revised cataloging is not shown. We hope to be more transparent in the next version of the website, which is planned for 2026. ↵

- Shukri Sultan, Endriana Audisho, Julia Ramos, and Jacqueline Tran, “Caption This,” CCA, November 2023, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/92693/caption-this; Jennifer Préfontaine, Michele Tenzon, Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall, and Rixt Woudstra, “A Matter of Terms,” CCA, accessed May 22, 2025, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/90189/a-matter-of-terms; and Nokubekezela Mchunu, “Drawing Connections,” CCA, 2022, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/98555/drawing-connections. ↵

About the Author(s): Martien de Vletter is associate director of collections at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA).