Contact, and Contact Again: Reflections on an Eighteenth-Century Powderhorn

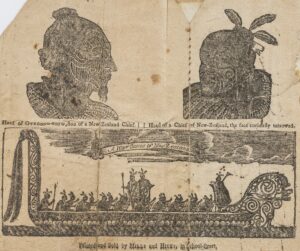

Jennifer Y. Chuong researches the eighteenth-century transatlantic world; Kailani Polzak researches European voyages in the Pacific; and we share an interest in print’s materialization of racial ideologies. When we were invited by Emily Casey to coauthor a response to the question “Where and when does colonial America end?,” it seemed like a perfect opportunity to consider an object that exceeds traditional field boundaries: a decorated powder horn, originating in New England but bearing traces of an image originating halfway around the globe.1 Emblazoned with the owner’s name (John Parker) on its convex side, the horn features in its inner curve a vignette of eight figures shown in profile in a distinctively articulated watercraft (figs. 1 and 2).2 Clusters of feathers atop the figures’ heads correspond to allegorical and descriptive images of Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Significantly, while the tableau bears signs of a direct encounter (note the unique hatching of each figure), it is also the product of visual mediation: the image is clearly based on a drawing of a Māori waka taua (war-party canoe) by Sydney Parkinson, artist on Captain Cook’s first voyage, which was translated into several prints that circulated in the eighteenth-century transatlantic world (fig. 3).

Based on the strength of the formal resemblance between print and carving, the fact of this borrowing has been recognized for some time and is regularly held up as the important feature of Parker’s horn—a feature that demonstrates the visual awareness of colonial Americans as well as their visual and cultural sensitivity (in that the source image was adapted to better represent Parker’s locality).3 And truly, the act of borrowing is both remarkable and poignant. Just as the watercraft on the Parker horn evokes a moment of encounter, Parkinson’s studies evidence that waterways were often spaces of mutual observation and negotiation. Nevertheless, we suggest here that these interpretations overlook the complexity of the horn’s representation, which offers an important corrective to the way we describe, and therefore understand, cultural plurality in colonial America.

As tempting as it is to read the tableau on the Parker horn as evidence of one settler’s curiosity and openness to Indigenous culture, violence—or undertones of violence—run through both the source image and its adaptation. The ornate stern and bow of the vessel on Parker’s horn are based on Parkinson’s studies of Māori waka taua observed in Aotearoa (New Zealand). On several occasions, Cook’s ship entered a bay and local iwi (people, often translated as tribe) sent representatives out in waka taua to ceremonially assert place and investigate the unfamiliar ship.4 British descriptions of these interactions often characterize Māori men as particularly bellicose, though it was British gunfire that killed and injured Māori individuals rather than the other way around. These narratives convey a sense of fear or wariness that Bronwen Douglas describes as “countersigns of Indigenous agency,” residues of the impact Indigenous people have on voyagers, expressed in affective or reactive language.5

In the 1770s, prints after Parkinson’s image, accompanied by narratives of conflict with Māori iwi, circulated widely in illustrated volumes of Cook’s voyage published by the British admiralty as well as in magazines and almanacs. There are at least two plausible sources for the Parker horn tableau, both of which traveled with statements of context (figs. 4 and 5). It is virtually impossible, therefore, that Parker did not know the Pacific origins of his source image. Yet despite likely knowledge of geographical distance and cultural differences, Parker clearly found in one of these imperial images a suitable template for representing local Indigenous persons. Indigeneity, this act of borrowing suggests, looked more or less the same to colonizers, whether it originated in Aotearoa or in the land they called New England—and it was made to look more similar via the dissemination of images throughout the empire.

The similarity of the Parker and Parkinson images lies not only in their visual appearances but also in their relational attitudes. Even as Parker altered Parkinson’s image to address his specific context, a sense of anxiety and need for domination carried through. Consider, for example, Parker’s interpretation of the Māori tewhatewha, a long-handled axelike club. Parker rendered these weapons as halberds—probably the closest analogue he had to the tewhatewha. By the late eighteenth century, however, halberds were antiquated weapons by British standards, and Parker’s specific evocation of the halberd may therefore have been a way of depicting the Indigenous figures as modern—yet not quite as modern as the colonizers. Transposed to the settler-colonial context of New England, Parkinson’s pictorial countersigns participate in what J. Kēhaulani Kauanui has termed “enduring indigeneity”—that is, they demonstrate how, across global distances, settler-colonial structures actively hold out against Indigenous peoples at the same time that Indigenous peoples “exist, resist, and persist.”6

By virtue of the layered image carved into its surface, Parker’s horn offers a particularly vivid record of Indigenous presence in the eighteenth century, but powder horns in general speak to the shared modernity of Indigenous and white persons because they were part of a contemporary technological assembly—guns—that both colonists and Indigenous persons used (figs. 6 and 7).7 Furthermore, horns in several prominent collections demonstrate that at least some Abenaki, Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk), Narragansett, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot individuals also decorated their horns with incised lines (figs. 8 and 9). While many of these carved horns feature abstract designs, several include figural elements and at least one, a powder horn reported to have been owned by Penobscot chief Joseph Orono, exhibits a vignette that documents European presence in the form of a three-masted ship (fig. 10). Yet while there has been a resurgence of interest in eighteenth-century American powder horns, virtually all the books, exhibitions, and websites addressing these objects focus on the powder horns that were made and owned by white settlers.8 Holding the medium up as an emblem of colonial ingenuity, self-sufficiency, and individualism, authors have claimed a place for the engraved powder horn as “one of the few indigenous art forms of colonial America.”9

The appreciation of powder horns as “art” stems from a larger inclusivity that has long defined the study of colonial America and has sponsored important disciplinary questions about what constitutes art and who makes it.10 At the same time, as the above quotation suggests, it is too often the case that the art of colonial America continues to be conceptualized as the art of European settler-colonists—thereby writing out the many arts practiced by actual Indigenous persons and, in so doing, implicitly perpetuating the narratives that settler-colonists told themselves about the primacy and distinctiveness of their actions. As Jean M. O’Brien argues in her study of textual accounts of New England, settler-colonists asserted that they were the first to establish social order and institutions, writing away the Indigenous communities on those lands. Read through O’Brien’s framework, “indigenous art forms” replicate the language of institution, here of art, and erasure in its place-based claim.11

§

Where and when does colonial America end? To our minds, the Parker horn suggests two ways of answering the question. The first, recognizing the global nature of Indigeneity and the ongoing appeal of colonial culture for national narratives, is: “It doesn’t, and it hasn’t.” As we suggested earlier, this answer demands that we rethink our characterization of cultural plurality in colonial America. While scholars have long acknowledged the multiculturalism of the quote-unquote New World, they have commonly described the interaction of cultures with words like “contact,” “encounter,” and “exchange.” These terms are problematic for several reasons. First, they imply a temporal discreteness—a completed transactional moment—that does not capture the deep influence that cultures exert on each other, the ongoing nature of their interactions, and the long half-life of intercultural apprehensions. Second, and similarly, these words imply a spatial boundedness. Contact happens between two groups that are physically co-present with one another (close enough to touch), whereas, in fact, cultural influences are pervasive and opportunistic—and therefore global, as we are increasingly coming to understand. Third, these terms connote a politics of neutrality to the encounter. While they therefore imply a mild affirmation of diversity, they also elide and perpetuate the asymmetries of power and intention that almost always underlie interactions between different groups of people.

With its bilateral decorative scheme, the Parker horn also intimates a different way of answering Casey’s question. To date, descriptions of the horn (including ours) have begun with the name and date inscribed on its outer side—with their forceful claims of identity, ownership, and meaningful place in American history—before turning to the tableau on its inner curve. The organization of the horn demands this: we can’t see both sides at the same time; one side therefore frames our reading of the other. Yet why do we not begin with the tableau? As with New England’s settler-colonists in O’Brien’s analysis, placing colonial America at the center of our discussion “firsts” the colonizers and ourselves as settler-scholars, making them/us the protagonists that define the beginning and end of the narrative. How might we upend this structure? What would it mean, for example, to understand John Parker not as a protagonist who reached across the globe and into the past to draw out an image of Māori individuals for his use but rather as a latecomer to a long, expansive history of Indigeneity—as a minor character or a footnote? What would it mean to understand this horn as imaging not the dilation of encounter into colony but the continuity of Indigenous contestation? Extending these questions, what would it mean to interrogate our Western notions of time and space, to imagine alternatives to the linear, forward march of modernity and the measured, finite space of coloniality? What would it mean to tell this story from the inside out?

November 23, 2021: An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of the Kanien’kehá:ka peoples.

Cite this article: Jennifer Y. Chuong and Kailani Polzak, “Contact, and Contact Again: Reflections on an Eighteenth-Century Powder Horn,” in “When and Where Does Colonial America End?” Colloquim, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12696.

PDF: Chuong and Polzak, Contact, and Contact Again

Notes

- The horn is currently located on lands that have been stewarded by the Pocumtuc and Kanien’kehá:ka peoples, in the collections of Historic Deerfield, MA. ↵

- Many John Parkers are listed on the militia rolls of 1775, and one John Parker did, in fact, lead the Minutemen to Lexington Green on April 19 of that year—though we have no documentation to determine whether he owned this horn or when it was carved. See William Guthman, Drums A’beating, Trumpets Sounding: Artistically Carved Powder Horns in the Provincial Manner, 1746–1781 (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1993), 160–61. (For expediency’s sake, in this essay we will refer to the carver of the horn as Parker, even though it is possible that it was carved by someone else.) As Guthman notes, the inscribed dates on powder horns are no guarantee that they were made or decorated in that year (20). The physical and emotional stress of war did not often lend itself to long periods of carving. However, Philip Zea notes that there were exceptions, as during long warm-weather sieges or other periods of inactivity; see “Revealing the Culture of Conflict: Engraved Powder Horns from the French & Indian War,” Historic Deerfield (Summer, 2008): 22). ↵

- An analysis of the tableau, for example, takes up most of the horn’s catalogue entry in the most substantial treatment of these objects to date: Guthman, Drums A’beating, Trumpets Sounding, 160–61. ↵

- Anne Salmond, Two Worlds: First Meetings Between Maori and Europeans, 1642–1772 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i, 1991), 125. ↵

- Bronwen Douglas, Science, Voyages, and Encounters in Oceania, 1511–1850 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 21. Douglas has discussed examples of countersigns in many of her publications. ↵

- J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “‘A Structure, Not an Event’: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” Lateral 5, no. 1 (2016), https://csalateral.org/issue/5-1/forum-alt-humanities-settler-colonialism-enduring-indigeneity-kauanui. ↵

- Beyond ownership by Indigenous and white persons, at least two powder horns from the Revolutionary period have been identified as belonging to Black individuals: Prince Simbo (1740 or 1750–1810, National Museum of African American History, Washington, DC) and Gershom Prince (1733–1778, Luzerne County Historical Society, Wilkes-Barre, PA). ↵

- An exception in this regard was the 2017 exhibition From Maps to Mermaids: Carved Powder Horns in Early America, Fort Pitt Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, which featured a section on Indigenous powder horns. ↵

- Zea, “Revealing the Culture of Conflict,” 20. Similar descriptions using the word “indigenous” or “native” are found in Guthman, Drums A’beating, Trumpets Sounding, 17, and Jim Stevens, Powder Horns: Fabrication and Decoration (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2010), 9. For descriptions more generally emphasizing the “uniqueness” of this art to North America, see Jim Dresslar, Folk Art of Early America: The Engraved Powder Horn (Bargersville, IN: Dresslar Publishing, 1996), xiv; and R. L. Wilson, The History and Art of the American Gun (New York: Chartwell Books, 2015), 58. ↵

- For the valuation of powder horns as art, see Julia Silverman, “Eighteenth-Century Powder Horns,” Art Conservator 11, no. 1 (2016), 5–7, 16. ↵

- In order to reconcile their narratives with irrefutable signs of Indigenous presence and history, colonial authors also relied on a rhetoric of “lasting” in insisting that Indigenous history had passed and that Indigenous peoples were bygone. Jean M. O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), xii–xiii. ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer Y. Chuong is the Terra Foundation for American Art Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at the Institut für Kunst- und Bildgeschichte, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Kailani Polzak is Assistant Professor in the Department of the History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of California, Santa Cruz