Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle

Curated by: Elsa Smithgall, Elizabeth Hutton, and Austen Barron Bailly1, with support from Lydia Gordon

Exhibition Schedule: Peabody Essex Museum, January 18–April 26, 2020; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2–September 7, 2020; Seattle Art Museum, February 25–May 31,2021; The Phillips Collection, June 26–September 19, 2021

Exhibition Catalogue: Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle. Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Austen Barron Bailly, eds. Peabody Essex Museum with University of Washington Press, 2019. 192 pp.; 82 color illus., 27 b/w Illus. Hardcover: $45.00 (ISBN: 9780295747040)

Jacob Lawrence’s series Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954–56) comprises thirty paintings completed at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, sixteen years after his better-known Migration series (1940–41). While the Migration paintings examine what has been referred to as the Great Migration, the movement of millions of African Americans from the rural South to northern American cities in the early to mid-twentieth century, Struggle addresses key moments in the American Revolutionary era and its aftermath to 1830. The exhibition Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, which I visited at The Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, presents this series in a museum setting for the first time. The reunited panels of the Struggle series are arrayed together in the main gallery space. The neighboring galleries focus on contemporary artists’ interpretations of American history and on Jacob Lawrence’s personal life.

The Struggle series emphasizes the ferocity of battles, rebellions, and conflicts from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, with particular attention to the historical actors who were usually excluded from accounts of the nation’s history in Lawrence’s time. This series presents a different tone and tenor than its predecessor Migration. The works are complex, layered, vivid, blunt, and tense. Lawrence’s diagonal, flat, and crisp silhouettes advance the urgency and gravitas of battles fought during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, as well as Shay’s Rebellion (1787) and Boxley’s Rebellion (1810). Lawrence’s former collaborator, artist and printmaker Lou Stovall, explains that Lawrence’s paintings are “adding a narrative, a sense of place and urgency.”2 Ellen Harkins Wheat noted that Lawrence, while drawing on modernist design principles, also incorporated a “reassertion of paintings’ narrative function.”3

When the exhibition was developed, three of the series’ thirty paintings were as yet unlocated, and two are too fragile to travel. The curators addressed these missing images by hanging empty frames and low-resolution images in their numerical order within the series (fig. 1). Miraculously, this exhibition has resulted in the discovery of two of the missing paintings from the series, which were incorporated into the Phillips Collection’s installation.

Lawrence titled many of the panels with quotations extracted from historic speeches and correspondence. Panel one, . . . is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? —Patrick Henry, 1775, introduces the series. This panel draws its impetus from the last lines of the politician’s famous speech, “Give me liberty, or give me death!,” delivered at the Virginia Convention in 1775. Motivated by Henry’s speech, Lawrence’s first panel sets the tone of the series. Agitation and disruption are conveyed through the jagged forms of Henry’s outstretched arm and the raised fists of the crowd below him, all rendered in vividly colored, layered planes of black, red, and brown with blue, yellow, and green contrasts. In another panel, Lawrence renders a precursor to battle in I alarmed almost every house till I got to Lexington —Paul Revere (No. 4 THE NIGHT RIDER). Lawrence’s interpretation of Revere’s night ride was inspired by poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s reimagining of the event in his 1860 poem “Paul Revere’s Ride.” The story’s nocturnal setting is rendered in a palette reduced to blue, brown, and black, while its drama is heightened by Lawrence’s enlargement of Revere’s pointing fingers, indicating and anticipating the arrival of the British troops. The horse is a focal point, framed by figures who express urgency in their taut poses, weapons gripped in their hands. Such historical moments resonated with Lawrence’s time in the military in the US Coast Guard during World War II.

Other panels take us into the crescendo of battle. Panel eight, . . . again the rebels rushed furious on our men —a Hessian soldier, describes the height of the Battle of Bennington in 1777. Bright red blood streams from wounded bodies in this collision of horses, men, and weaponry. Dramatically contorted facial expressions convey the shock and agony of battle. Panel twelve, And a Woman Mans a Cannon, depicts the beginning of the Battle of Fort Washington on Manhattan Island. In this panel, one of only two in the series to feature women, Lawrence represents Margaret Cochran Corbin, who served in the Revolutionary War. Her body frames the entire left side of the panel as she fires her cannon.

Growing up in Harlem, New York, during the Great Depression, Lawrence was intimately familiar with American experiences shaped by failures in the nation’s financial and social infrastructure. His early formal artistic training was developed at the Harlem Art Workshops, which were supported by the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). By the age of twenty-one, he had become an easel painter for the FAP in Harlem. The largest Black urban community in the United States, Harlem of the 1930s was crowded, multifaceted, and sophisticated.4 This social and cultural milieu provided Lawrence with a great deal of inspiration. Over more than five decades, Lawrence’s art engaged with themes centering on the struggles and the challenges facing African Americans.5 According to the exhibition catalogue, Lawrence had compiled his own archive of clippings related to his investigations into American history.6 This focus on providing a nuanced rendering of American historical narratives constitutes the core of his numerous print and painting series.

The Phillips Collection is a unique exhibition space. The panels of Struggle are divided among five small galleries across the second floor. This floor plan presented an opportunity for curators to think creatively about the series’ placement and layout in relation to accompanying contemporary art from Bethany Collins, Derrick Adams, and Hank Willis Thomas. One of the distinctive characteristics of The Phillips Collection is that it was once the residence of its namesake, art collector and critic Duncan Phillips. The rooms, replete with fireplaces and bay windows, were originally functional bedrooms for its former residents. These various juxtapositions of domesticity and contemporary museum space offer an extraordinary exhibition-viewing experience, providing a quiet, meditative space for contemplation and reflection. The contemporary works of art by Collins, Adams, and Thomas flank the main exhibition space in smaller rooms adjacent to where the Struggle series is presented.

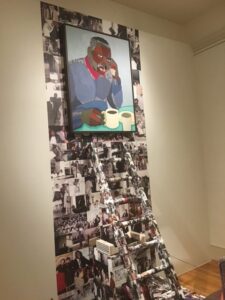

These neighboring spaces exhibit Bethany Collins’s American: A Hymnal, a book of one hundred laser-cut leaves; Hank Willis Thomas’s series of photographs titled My Father Died for This County Too / I Am an American Also and his sculpture Rich Black Specimen #460 (fig. 2), and Derrick Adams’s art installations Saints March and Jacobs Ladder (fig. 3). These works are reflective of Lawrence’s influence on contemporary art and practice. In Jacob’s Ladder, Adams incorporates Lawrence’s favorite armchair from his studio, a portrait of Lawrence, and a record player with a montage of photographs that captured tender moments with friends and family, as well as milestone events. In an essay for the catalogue, Adams cites Lawrence as a major influence on his work. He reflects on meeting Lawrence and his wife, artist Gwendolyn Knight, while a student at the Pratt Institute in New York. Thomas’s sculptures and photo series engage with the past and present simultaneously, incorporating flat, bold silhouettes similar to Lawrence’s style. Also, like Lawrence, Thomas believes that “visual history must be reinvestigated, repositioned, reimagined, and re-presented.”7 Collins’s installation includes wallpaper and a hard-bound hymnal. She writes in her essay: “As with all my work, America: A Hymnal grapples with identity, history, and language.”8 Elements of her installation are aligned with Lawrence’s use of text and images to provide a striking narrative of American history.

Lawrence’s Struggle series, as the catalogue notes, was inspired by historical documents, serials, and books addressing American history. How the notion of “struggle” is contextualized broadly in this exhibition is unclear. The contemporary artworks included attempt to make a connection to Lawrence’s theme, yet the exhibition does not specify these linkages clearly. For museum visitors, it is perplexing how these contemporary works—with the exception of Adam’s installation Jacob’s Ladder, which includes photos of Lawrence and a painted portrait (see fig. 3)—relate to the Struggle series (even though the exhibition catalogue’s essay attempts to connect the works conceptually). In the catalogue, Lydia Gordon claims the series “occasions a reconsideration of the artist and Struggle with the context of current debates about democracy, justice, truth, and the politics of inclusion.”9 However, this contextualization does not seem to follow the intent of Lawrence’s series. One may ask, how does Lawrence’s depiction of a country’s struggle, in the infant years of the republic, to assert itself as an independent nation translate to the struggle of the African American community in the wake of injustice, discrimination, and racism in the United States of today? The “conceptual pillars” that Gordon identifies can be found in most contemporary art. Collins, Adams, and Thomas grapple with particular issues that are a part of America’s historical past.

Yet the timing and historical relevance of this exhibition is apropos. As the United States is experiencing a reckoning with its fraught and contentious history, Lawrence’s Struggle series and the contemporary works by Collins, Adams, and Thomas illustrate the tensions of a relatively young nation establishing its independence while also facing the challenges of unresolved issues involving inequality and exclusion. The historical war battles and the struggles that Lawrence renders pose enduring questions about America’s past and its desired future. Engaging with American history through works like Lawrence’s series provides viewers with an opportunity to observe the nuances of what it means to struggle in the effort of shaping a better and more equitable future in new pictorial and conceptual ways.

March 11, 2022: An endnote was added to disclose Austen Barron Bailly’s affiliation with Panorama.

Cite this article: Janell B. Pryor, review of Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, The Phillips Collection, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12765.

PDF: Pryor, review of Jacob Lawrence

Notes

- Austen Barron Bailly is a member of Panorama’s Advisory Council ↵

- Lou Stovall, “Working with Jacob Lawrence: An Elegy,” Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art 36 (2002): 194. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence and the Legacy of Harlem,” Archives of American Art Journal 30, no. 4 (1990): 126. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,”119. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,”119. ↵

- Austen Barron Bailly, Lydia Gordon, and Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “Jacob Lawrence’s Research for the Struggle Series,” in Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, ed. Elizabeth Turner and Austen Barron Bailly (Peabody Essex Museum with University of Washington Press, 2019), 162. ↵

- Hank Willis Thomas, “Contemporary Artists Statements and Plates,” in Turner and Bailly, Jacob Lawrence, 145. ↵

- Bethany Collins, “Contemporary Artists Statements and Plates,” in Turner and Bailly, Jacob Lawrence, 143. ↵

- Lydia Gordon, “History Forward: Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle Series and Contemporary Art,” in Turner and Bailly, Jacob Lawrence, 130. ↵

About the Author(s): Janell B. Pryor is Assistant Professor of Visual Culture at Bowie State University and doctoral candidate in US history at Howard University