Transformation on the Plains: The Extermination of the Buffalo and a Way of Life

(Yurok Tribe)

Where does colonialism end in the United States? If we are talking about the land, it does not; the occupation of the United States is near total. White settlers’ colonization of this country, which spread across the land under the banner of Manifest Destiny, forever changed the landscape and the life it supported. And yet, it is not possible to colonize the heart of a people. As long as they live and recognize themselves, there is an outer boundary of colonization. For Natives, the evidence of this perseverance can be found in enduring images and symbols of lifeways as manifest through artistic production.

Native American art is constantly in motion and changes rapidly in response to the conditions surrounding it. Circumstances ranging from the arrival of the first Europeans on Turtle Island to the US government’s efforts to assimilate Natives into white culture had clear effects on Native material culture. The late nineteenth century was no exception—it was a period of trauma and immense transformation for Native Americans located on the Plains, and this context can be felt in the art from the period. As we lack robust historical documentation written from Native perspectives, historic photographs coupled with Native art can bridge gaps in our understanding.

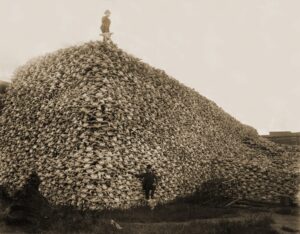

No one image can truly encapsulate the sea change of that time as much as the shocking 1882 photograph of a mountain of buffalo skulls dwarfing two grown men (fig. 1). This photograph provides evidence of the wanton greed, brutality, and vicious calculation that emerged from nineteenth-century settler colonialism. Reminiscent of the biblical Golgotha, the Khmer Rouge’s Killing Fields, and the trophy photographs American soldiers took of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, this imagery evokes an archetypal visualization that emerges again and again at scenes of destruction, dehumanization, and genocide.

To fully grasp the gravity of the image, we must understand the importance of the buffalo to Natives on the Plains and consider how foundational the creatures were to traditional lifestyles. The material culture of Natives living in that region can be read as a register of modes of living, worshipping, and maintaining culture. Prior to the Reservation Period, the buffalo served as an emotional and physical center for all aspects of Native sociocultural existence, as the animals were a major force driving nomadic life. This fact was not lost on the US military leaders who wished to subdue Natives and force them onto reservations in the late nineteenth century. US governmental authorities, recognizing that they lacked sufficient troops and the know-how to win against the Natives who employed guerilla warfare tactics, turned their sights to cutting off essential resources. The eradication of the buffalo was the straightest path to victory, because buffalo were so essential to Native livelihoods—they provided food, shelter, warmth, and protection. Moreover, many tribes viewed buffalo as sacred beings, so the species’ extermination would both starve and demoralize them.

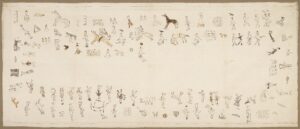

One artwork type that reflects Plains Natives’ reverence for the buffalo was the Winter Count—a visual calendar created by certain tribes that utilized a representative image to reflect a key event that took place between the first snowfall of one year and the first snowfall of the next year. Winter Counts were used as mnemonic devices that assisted the artist, or “Winter Count keeper,” in recounting historic events that shaped tribal life, be they encounters with massive buffalo herds or military skirmishes with neighbors.1 In that way, they were and continue to be excellent teaching tools that speak to the conditions of life over multiple generations. The Winter Count created by Lone Dog (fig. 2), a Nakota man, features numerous calendar entries that focus on buffalo; two such illustrations show an abundance of buffalo meat curing for one year and rows of buffalo hoof marks next to tipis for another.2 The fact that buffalo appeared as the major highlight for many years demonstrates how essential the animals were to Native life.

In the decades following the creation of the Long Dog Winter Count, many white settlers engaged in the extermination of the species for sport, a practice fundamentally antithetical to Native belief systems. During the mid-nineteenth century, there were an estimated fifty to sixty million buffalo living on the Plains, and around two hundred thousand buffalo were killed each year to support tribal life.3 With the completion of the railroad, however, the eradication of the species escalated dramatically. Renowned nineteenth-century American zoologist and conservationist William T. Hornaday claimed that over 3.1 million bison were slaughtered between 1872 and 1874 alone, and of those, nearly 1.8 million were killed and left to rot in the sun.4 By 1889, only two hundred buffalo lived in the wild, kept under US Government protection in Yellowstone National Park.5

Manifest Destiny went hand in hand with both the loss of the buffalo and Natives’ compulsory move to reservations. For Natives, these twinned events were symbols of the loss of their lifeways, freedom, and pride; for whites, they were symbols of conquest. The enormous cultural transformation the events represented was met with responsive and dynamic Native artistic expression. Materials available for art shifted—where buffalo hides were once used, cattle hides or manufactured cloth were employed instead. In the case of Winter Counts, artists began to use canvas and muslin cloth instead of buffalo hide, evident in the Hunkpapa Lakota artist Long Soldier’s Winter Count (fig. 3).

Like Lone Dog’s Winter Count, the Long Soldier Winter Count includes several allusions to buffalo, some of which point to the destruction of the species. One entry of note is the image for the years 1883 to 1884, which depicts the Standing Rock Reservation Agent White Beard (Major McLaughlin), “[who] organized and hunted in Standing Rock’s last buffalo hunt [in which] 5000 animals were killed.”6 Although the form and imagery of Winter Counts transformed during this pivotal period, their function persisted as they continued to commemorate important moments for the tribe. Sadly, the last buffalo hunt was formative in Lakota identity: in the years following this entry, the tribe was unable to hunt, which meant that they could never return to their ancestral way of life.

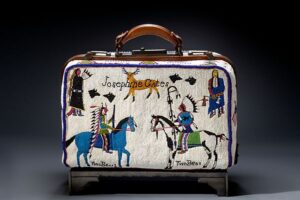

Evidence of cultural transformation also appears in art created by women. In the middle to late nineteenth century, beadwork supplanted traditional quillwork, and female artists broke from long-held stylistic traditions. Instead of only utilizing geometric designs, they began to actively collaborate with men to create figurative works and, at times, employed figuration entirely on their own. These adaptive strategies were essential for cultural continuity, as they maintained artistic traditions and told histories that may have otherwise been lost.

One artist of particular acclaim was Nellie Two Bear Gates, a Lakota woman who hybridized Anglo-American objects with Native aesthetics through the application of beadwork. Upon her daughter Josephine’s graduation from Carlisle Indian Boarding School in 1903, Nellie created a fully beaded valise that depicts important historic events, including her tribe’s last big buffalo hunt in 1882 (figs. 4a, b). Unlike the Winter Counts, objects like this valise illustrate how Native artists took up Euro-American forms but maintained cultural continuity with both the narrative imagery and visual vernacular. The same could be said of beaded gauntlets and vests, as both forms were appropriated from Euro-American culture and then reinvented to serve Native people’s needs. Works of this type are markedly different from traditional objects like Winter Counts, as they strike a balance in communicating assimilationist and culturally preservationist intentions.

Without the buffalo and requisite activities like tracking and hunting, the fabric of life on the Plains unraveled. As mountains of buffalo skulls reached skyward, the environment was irreparably damaged, and colonialism marched on. And yet Native people were not defeated; they found inventive ways to carry on their cultural and artistic traditions through the use of new materials and the innovation of new forms. Native people adapted to new circumstances and persevered. Though the United States will always live in the shadow of colonialism, Native hearts and spirits were never and will never be truly colonized. In the case of Natives living on the Plains, the historic loss of the buffalo led to innovative art practices, and the threads of those unraveled lives were woven together to create something new.

Cite this article: Darienne Turner (Yurok Tribe), “Transformation on the Plains: The Extermination of the Buffalo and a Way of Life,” in “When and Where Does Colonial America End?” Colloquium, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12727.

PDF: Turner, Transformation on the Plains

Notes

- Candace S. Greene and Russell Thornton, The Year the Stars Fell: Lakota Winter Counts at the Smithsonian (Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, 2007), 20. ↵

- Greene and Thornton, Year the Stars Fell, 159. ↵

- Gilbert King, “Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 17, 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-the-buffalo-no-longer-roamed-3067904. ↵

- William T. Hornaday, The Extermination of the American Bison (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum, 1889), 498. ↵

- Hornaday, Extermination of the American Bison, 464. ↵

- Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote, “Introduction to the MIA Long Soldier Winter Count,” guide to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2004, http://www.ipevolunteers.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Lakota-Winter-Count-Additional-Information.pdf. ↵

About the Author(s): Darienne Turner (Yurok Tribe) is Assistant Curator of Indigenous Art of the Americas, Baltimore Museum of Art