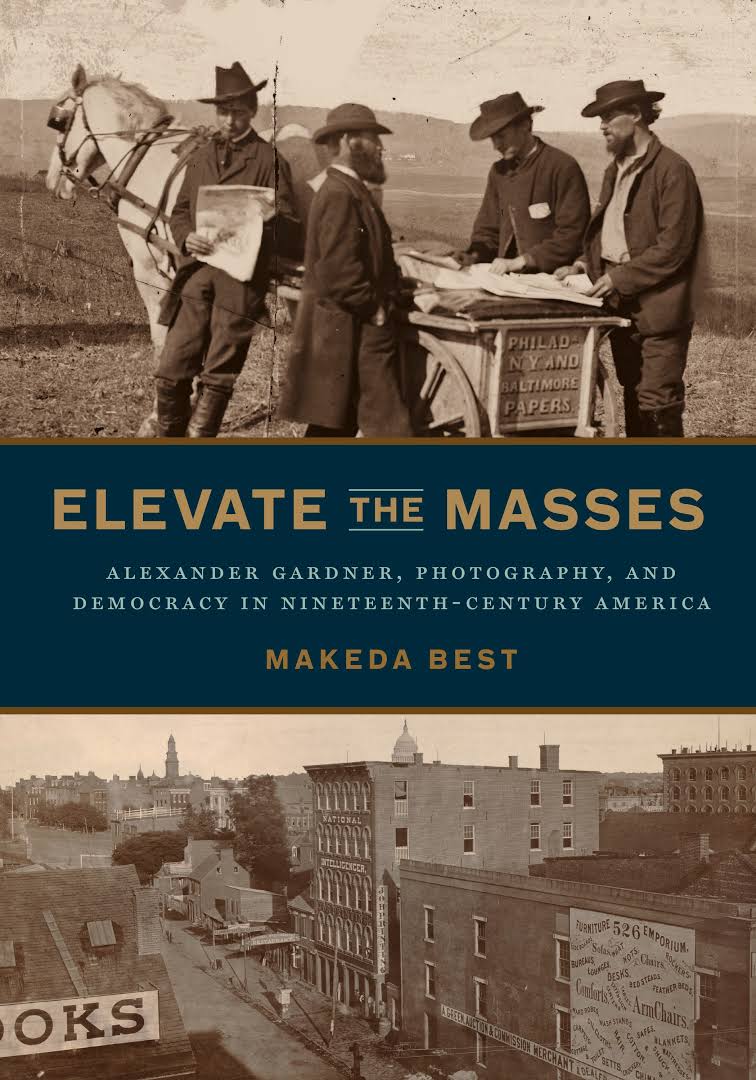

Elevate the Masses: Alexander Gardner, Photography, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century America

PDF: Parker, review of Elevate the Masses

Elevate the Masses: Alexander Gardner, Photography, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century America

by Makeda Best

University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020. 200 pp.; 84 b/w illus. Hardcover: $69.95 (9780271086095)

Long before the publication of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1866; hereafter Sketch Book) and prior to his emigration from Scotland to the United States, Alexander Gardner’s life and career already had included two remarkable experiences: ownership of the prolabor newspaper Glasgow Sentinel, 1851–56, and investment in a utopian community, the Clydesdale Colony in Clayton County, Iowa, around 1849–50. Both were sparked by Gardner’s embrace of Chartism and Owenism, two ideologies that shaped his thinking before and well after his move to the United States. Makeda Best1 explores in depth Gardner’s unwavering belief in democracy and democratic ideals, a commitment largely shaped by these reform-minded ideologies popular in the nineteenth century. Indeed, she argues that the ideologies and values of the “transatlantic reform community,” which included Chartists and Owenists, significantly impacted the historical narrative of the Civil War and the post–Civil War North that Gardner presented in Sketch Book.

Early in her text, Best provides a nuanced and engaging overview of Chartism and Owenism. The former, originating in Great Britain during the late 1830s and emerging as an economic and political reform movement in the 1840s, proposed a series of government reforms, called the “People’s Charter,” that would “empower the working classes” and provide greater economic and social parity across class lines (2). Similarly, the social reforms advocated by Robert Owen also pushed for improvements in the lives of the working classes of Scotland. Additionally, Owenites saw a need for “moral reform” that could curb the chaotic rise of the free market and industrialization and lead to the development of systems for common ownership of resources and production. Gardner, fired up by these ideologies, cofounded the Clydesdale Colony, which followed Owen’s protosocialist ideas about collective communities.

Gardner’s investment in the Sentinel and his five years as its publisher and as one of its editors gave him a regular public platform for exploring and deepening his beliefs regarding the rights of the working classes. Throughout Elevate the Masses, Best mines the Sentinel editorials and articles published during Gardner’s tenure in order to reveal clear connections between the visual and textual rhetoric of Sketch Book and his Chartist and Owenite values. She also extensively examines Gardner’s editorial work with the Sentinel in order to demonstrate his dedication to the rights of the working classes and faith in democracy as a beacon of hope and change.

In her first chapter, Best imaginatively juxtaposes the writings of Gardner found in two of his publications, Rays of Sunlight from South America (1865) and Sketch Book. She analyzes the visual and textual content of both as evidence of his steadfast hope in the promise of American democracy and its position as the source of moral, social, and economic progress. Rays of Sunlight provides a broad and rather simplistic overview of the political and historical conditions of Peru, which Gardner positioned as the cautionary tale of what happens when a nation fails to change and embrace democracy. The earlier book clearly serves as a foil to Sketch Book with its focus on the post–Civil War United States. Best also here addresses the scholarship of Anthony Lee and Jeff Rosenheim, highlighting their argument that a commercial and financial lens substantially influenced how Gardner conceived and edited Sketch Book. She, however, aligns her analysis much more closely with the literary scholarship of Timothy Sweet and Megan Rowley Williams; both understand Sketch Book as a visual means for building the nation through presenting the “pastoral mode as a path to national reunion” (21).

Best identifies various tendencies and tropes in Chartist literature that occur repeatedly in Sketch Book, including the voice and point of view of the traveler in a travelogue. She chronicles how nineteenth-century British reformers and reform-minded publications, like the Sentinel, often featured stories (“sketches”) of firsthand observations by recent immigrants or visitors to foreign lands. In addition to the voice of the informed travel guide, Gardner’s frequent descriptions of natural resources and the geography of Civil War sites in Sketch Book derived, according to Best, from Gardner’s Chartist-Owenite values, which placed a high premium on land, specifically agrarian land, as an agent for moral, social, and economic uplift. The Sketch Book photographs selected by Best as expressive of Gardner’s values, such as Timothy O’Sullivan’s Fredericksburg, VA (March 1862), do indeed seem to capture both clear destruction from the war and signs of recovery or infrastructure that survived with little or no damage. Best deftly expands on the arguments of Sweet and Williams by demonstrating that Gardner’s constant evocation of nature and specific geographic sites in the captions for the photographs in Sketch Book is deeply rooted in his Chartist-Owenite beliefs that preceded his move to the United States. Rather than dwelling on the damage to the land wrought by Civil War battles, Gardner’s captions emphasize the agrarian abundance, beauty, and diversity of specific sites and “natural” cycles of “revolutionary” change, which Best identifies as similar to the trope of upheaval in nature found in Chartist poetry (43). Embedded within such cyclical upheaval and change is the promise of an “agricultural future” and a “new nation of moral as well as fiscal tranquility and prosperity” (44).

Chapter 2 analyzes William Pywell’s photograph Slave Pen, Alexandria, VA (1862), the only photograph in Sketch Book that directly concerns slavery, in comparison with photographs of African Americans taken in the early to mid-1860s by Gardner and others. Best provides a comprehensive visual and contextual examination of Slave Pen, which features buildings of the slave-trading firm Franklin & Armfield, in order to demonstrate how it aligns with the visual and textual strategies of late eighteenth-century British abolitionists, whose work Gardner would have known. She does a fine job providing the reader with a succinct yet deeply informative overview of the symbolic and rhetorical value of the slave pen in the antislavery movement and discusses at length the Sentinel as an abolitionist voice in the 1850s.

As she engages in extensive visual analysis and critiques of representations of Black bodies, however, her interpretations of some of these images falter a bit. One secondary claim that weakens this chapter is Best’s insistence that Pywell’s decision to make the road in front of the building the central feature of the image—dividing it on a diagonal—“re-creates metaphorically the traffic of slave bodies from the Virginia farms to the slave pen and out of the space of the photograph and toward the wharf, from which the slaves would begin their southward journey” (65). Pywell’s point of view from across the road seems to me more likely derived from an interest in showing the scale of the slave pen, a compact, one-story building, in contrast to the offices of Franklin & Armfield next door. Furthermore, the stretch of road leading to the wharf is blocked by a tree and its branches. Gardner’s lengthy caption for the photograph does state that “‘the threat of being sent South [was] constantly held over the servants as security for faithful labor and good behavior’” (54). Still, the composition of the photograph does not really suggest an assertive focus on the horrors of enslavement. Her visual analysis of Gardner’s photograph Slabtown, Hampton, VA (1864) is more convincing in its claim that this image of a community established by Union officials for newly freed African Americans was intended to suggest for a Northern audience that the inhabitants were “simple-minded folk, seekers of home and honest work” (83) and to showcase “the role of good government as protector of those who have suffered” (84).

Best discerns an “inherent racism” in Gardner’s photos of African Americans in which they appear as a subject that is “intrinsically incapable” and therefore in desperate need of Northern aid (82). Yet, such a generalization becomes problematic when considering Gardner’s photograph Richmond, Virginia. Group of Negroes by Canal (1865), which, according to Best, shows African Americans still in “the position of the supplicant slave,” despite their recent emancipation (81). When taking a closer look at this photo of four children and several men, one sees a range of poses and body language—some stand; others are seated atop a fence, legs crossed, torsos erect, and gazing directly at the camera; many look rather self-assured and deeply aware. Gardner’s representation of African Americans may be, overall, severely limited and problematic, but this single photo suggests possibly a more nuanced perspective.

Chapter 3 examines representation of the army “rough” or lower-class Union soldier in Sketch Book as Gardner’s idealized vision of the manual laborer/artisan. Best provides several thoughtful analyses of both the images and the accompanying texts that capture Union soldiers engaged in the skilled labor that supported the war effort—building roads, making tents, constructing fortifications, logging trees, and forging horseshoes. Additionally, she skillfully weaves into this chapter the impact on Gardner of the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London, which occurred during his first year as owner/editor of the Sentinel. Gardner, Chartists, and other prolabor advocates noted the conspicuous absence of displays that recognized and honored the work of those who had made the numerous industrial objects presented at the exhibition. Sketch Book thus serves as an indirect yet deliberate corrective to the lack of respect and concern for the working-class laborer that Gardner witnessed in the United Kingdom prior to his move to the United States.

Chapter 4 provides readers with a fascinating look at Gardner’s series of postwar photographs of federal buildings in Washington, DC. These images gave him not only another arena in which to express his Chartist and Owenite beliefs about the virtues of democracy but also an opportunity to showcase the promise of America as a nation of genuine “access and circulation” for everyday people (123). Best convincingly demonstrates that the “commanding” vantage points and lighting utilized by Gardner when photographing buildings like the Patent Office or the Executive Mansion were a deliberate effort to give them a monumental, dramatic quality that conveyed his faith in “the nation-state as the force that promotes economic well-being and guarantees liberty” (131). Indeed, when she compares Gardner’s photograph of the Patent Office to John Plumbe’s 1846 photograph Old Patent Office Building, one can immediately sense the effectiveness of Gardner’s strategy to express what is essentially his immigrant optimism about the promise of a postwar egalitarian United States.

In her concluding chapter, Best addresses the multiple ways Gardner’s reformist conception of America was flawed, such as the lack of self-awareness “of his own class difference and privilege” and “his romantic perspective of labor and laborers” (150). Nonetheless, she accurately characterizes Gardner’s work as breaking new ground for US photography, specifically as forging a path for later documentary, “socially minded” photography in the twentieth century. A major contribution to the study of US Civil War photography, Elevate the Masses deepens our knowledge of the genre and makes abundantly clear the position of Gardner’s work on the continuum of reform photography.

Cite this article: Shalon Parker, review of Elevate the Masses: Alexander Gardner, Photography, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century America, by Makeda Best, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15204.

- Best is a member of Panorama’s Advisory Council. ↵

About the Author(s): Shalon Parker is Professor of Art History in the Art Department at Gonzaga University