Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015; 224 pp.; 131 color illus.; 27 b/w illus.; ISBN 9780226192130; Cloth: $45.00

The inscription that appears on the majority of the activist’s commissioned cartes de visite, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance. Sojourner Truth,” is commonly known today, and Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, in Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance, fleshes out and dissects these portraits and their famous phrase in an in-depth, original, and fully investigated manner. Grigsby’s reputation as an internationally regarded scholar of French and transatlantic studies precedes her. With Enduring Truths, she firmly establishes her authority as a historian of American photography, as well.

The inscription that appears on the majority of the activist’s commissioned cartes de visite, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance. Sojourner Truth,” is commonly known today, and Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, in Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance, fleshes out and dissects these portraits and their famous phrase in an in-depth, original, and fully investigated manner. Grigsby’s reputation as an internationally regarded scholar of French and transatlantic studies precedes her. With Enduring Truths, she firmly establishes her authority as a historian of American photography, as well.

Grigsby accomplishes a surprising depth of scholarly analysis within the space of a standard academic monograph. She highlights Truth, her lifelong quest for equality, and the remarkable control she had over her own identity throughout, insisting that “Sojourner Truth was the author of her representation and its circulation during and after the Civil War.” (115) Grigsby also provides a fully contextualized history of the carte de visite form in America during its initial period of popularity, as well as the ways in which these photographs were used for political purposes, establishing their impact as “tools of war.” (7) Grigsby beautifully describes Truth’s cartes de visite as “meditations by a former slave on value and authorship” (123) and explores these ideas through investigations of the iconography of the photographs, her illiteracy, her autograph collection, photographic albums, and more. She emphasizes the significance of the medium of photography for Truth and claims that Truth knew how important the invention of photography was “for a society attempting to redefine the status of black men and women.” (12) Throughout the text, Grigsby signals the counterarguments that photographs could offer and probes the particularities of the artist’s use of photography to address the significance of her image within the wider history of nineteenth-century visual culture. In doing so, Grigsby establishes the place of her volume within academic literature, writing, “While several related articles have been written in the last decade, this is the first book devoted to Sojourner Truth’s remarkable use of photography and its newly popular form, the inexpensive and diminutive carte de visite, in the context of the Civil War.” (11)

Furthermore, Grigsby connects Truth’s images to the history of nineteenth-century currency and the study of photography and copyright before 1865. The author’s in-depth discussion of copyright law, tedious as it may be, is absolutely necessary to establish Truth’s unique acquisition of copyright, and it reinforces the arguments regarding ownership of one’s image. Grigsby ultimately argues that Truth’s portraits, attached to cardstock and widely distributed, should be seen as “paper that stood for economic value” and served as a stand-in for currency. (153) Because Truth supported herself and her causes with the sale of her photographs, Grigsby asserts that her photographs were her currency. She also extends this idea to consider the social currency of the carte de visite, thereby adding additional layers of meaning to the photographs.

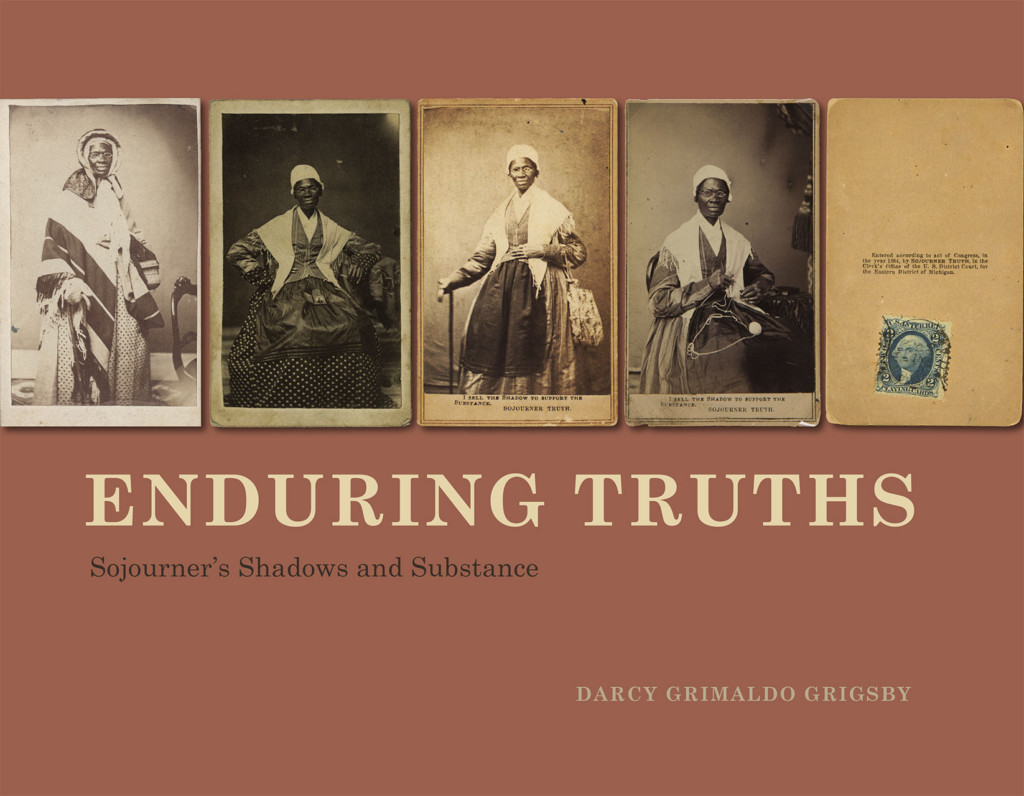

Tracing Truth’s photographs chronologically, Grigsby dissects their contextual variances in multifaceted ways. She bookends her project with an examination of the first and last photographs for which Truth sat. Both images fall outside of what became the standard style for her portraits, but they offer a powerful poignancy. For example, in describing the first extant portrait of Truth in which she appears almost lost in multiple layers of fabric, Grigsby adeptly notes the paradox in her appearance. She was in control of her speech to a pro-slavery audience in Indiana, but she was dressed and posed by abolitionist ladies who, significantly, hid her black body. By tracing Truth’s photographs over the course of several years, Grigsby works to locate Truth’s “identity” in the photographs beyond this initial work and reveals her “eventual relaxation in front of the camera.” (76)

Throughout the text, Grigsby presents Truth as brave for sitting before the camera. She examines twenty-eight different photographs of Truth, mostly taken during the Civil War and at the end of her life, in the early 1880s. The author’s task was not straightforward, as so many of the cartes de visite, which Grigsby describes as “complex, multilayered things,” look similar. (20) By distinguishing among individual poses, sittings, and sessions, and clearly acknowledging differences, Grigsby keeps the nuanced changes within each individual work clear and organized. Furthermore, she investigates the connections between the visual and the textual by considering Truth’s illiteracy and its impact on her life, acknowledging that the archival record, tempered through a third person, might not be completely accurate. Remarkably, despite her illiteracy, Truth was the publisher, printer, and seller of her own book; her first autobiography was published in 1850 and later reissued.

Investigating Truth’s portraits from multiple angles, Grigsby dissects Truth’s oft-repeated photographic inscription, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” and connects Truth’s use of the word “sell” with nineteenth-century slavery. Grigsby argues that Truth, as a former slave, was signaling her right to sell her own image. She underscores that Truth wanted to fight for the Union, but since she could not, she sold her photographic image instead, which she called her “shadow.” However, Truth swelled with pride over her grandson’s enlistment in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and, in Michigan, she sat with his portrait on her lap in at least four different portraits. Grigsby additionally argues that the metaphor of the shadow is “far stranger than scholars have acknowledged” and cites a range of period references to shadows, from photographs to shadow puppets, in support of her claim. (86)

Primary consideration is given to the groups of copyrighted portraits taken of Truth after 1864, which Grigsby describes as replacing “the personal and familial with an identification with the government, the law, and the Union cause.” (69) A discussion of the connections among ownership of one’s image, who profits from it, and how it was distributed helps place Truth’s photographs within the wider circulation of images of former slaves and the ways in which such images were used for a variety of fundraising efforts in the years during and after the Civil War. When copyrights were first taken out in 1864—and few actually were—the copyright was given to the photographer, not the sitter. Significantly, as Grigsby points out, Truth’s are the only photographs of the period that were copyrighted by the sitter, and they are part of a small surviving group imprinted with the sitter’s name (both front and back). Truth demanded the inscription of her name, perhaps because she had no “socially acceptable or literate” signature with which to sign it, but more likely because she relied on “the shadow” for her livelihood. (141)

This highly readable volume is conveyed in lucid prose that lays out the practical context of Truth’s cartes de visite in the 1860s and 1880s (the decades during which she sat for the vast majority of them) while weaving in details from Truth’s significant life story. Because the academic jargon has been wiped away and the writing is clear and easy to follow, this volume will appeal to a range of readers, including students, academics, and history buffs. Language use is illuminating, as when the author describes paper in the Civil War as being “circulated promiscuously.” (21) Throughout, Grigsby makes extensive and effective use of quotations, applying the words of others to ground and elucidate the broader story. Significant excerpts at each chapter heading draw the reader in and set the tone for the text that follows, while Grigsby is clear in her descriptions, italicizing important aspects of quotations and reemphasizing those in the analyses that follow. At times, the text is in the first person, a usage not generally applied in academic writing. This was clearly a self-conscious choice on the part of the author and parallels Truth’s emphasis on the personal: “I sell the shadow.” By using the first person, Grigsby reveals her personal connection with the material (notably, many of the illustrations are from her own collection).1

Similarly, the illustrations are novel. Although Truth’s likeness is familiar, based on the wide reproduction and distribution of these that continues today, the nuances of her portraits are particularized by Grigsby. Part of the power of the book today lies in its assemblage and circulation of the full body of Truth’s portraiture. The images Grigsby utilizes for comparison and context are effective and fresh. Necessarily, some frequently illustrated examples are included, such as The Scourged Back, showing Gordon’s scarred and twisted back. Comparing the image of Truth with the image of Gordon, Grigsby argues that, “Truth offers herself as a model for an emancipated, prosperous African American future, a model worthy of emulation,” one different from those who were depicted as victims or martyrs. (79) Primarily, however, Grigsby includes highly original visual comparisons throughout the text.

A history of the full scope of Truth’s photographic images is a welcome addition to the field and accords nicely with recent exhibitions and publications about Frederick Douglass and subjects related to the photographic record of the period.2 The form and layout are visually beautiful, setting it apart from these other volumes. The glossy pictures in full color provide a marvelous exception within the current academic publishing market. Ultimately, Enduring Truths combines many of the aspects that comprise the best in art historical scholarship. It is an interdisciplinary wonder that is part biography, part iconography, and part analysis. For anyone interested in the significant impact of Sojourner Truth and her photographs on the nineteenth century, I recommend a cover-to-cover read of this important text.

Cite this article: Rachel Stephens, review of Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance, by Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1619.

PDF: Stephens, Enduring Truths

- Many of these were exhibited in “Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery” curated by Grigsby, Stephanie Cannizzo, and Ryan Serpa, July 27-October 23, 2016, UC-Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Reviewed by Jackie Clay in Panorama 3:1 (Summer 2017). ↵

- See for example, John Stauffer and Zoe Trodd, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: Liveright, 2015), which accompanied the exhibition presented through December 2017 at the Museum of African American History, Boston; Marcy Dinius, The Camera and the Press: American Visual and Print Culture in the Age of the Daguerreotype (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012); and Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds. Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2012). ↵

About the Author(s): Rachel Stephens is Assistant Professor of American Art at the University of Alabama.