Ex-Artists in America

PDF: O’Donnell, Introduction to Ex-Artists

Contributors

Paul Staiti, “Jilted: Samuel F. B. Morse at Art’s End”

Diana Strazdes, “The Artistic Life and Afterlives of William James Stillman”

Chloe Julius, “Lee Lozano’s Revolution, or the Politics of Quitting Art at the End of the 1960s”

Tom Day, “‘No Art’ Protests: Restricting and Withdrawing Artistic Labor Downtown, 1961–1986”

Introduction

Taking inspiration from the “Great Resignation” of recent years, as well as from popular attention that has been given to resigning, withdrawing, and giving up, this collection of essays focuses on prominent examples of artists who abandoned art making—either for good, temporarily, or arguably only performatively—in order to query the shifting place of quitting in the history of art of the United States.1 Samuel F. B. Morse, William James Stillman, Lee Lozano, and Tehching Hsieh, the protagonists of these collected essays, are hardly marginal figures in American art history. And yet, considering these artists together—or any other diachronically wide-ranging set of artists who “quit,” for that matter—has somehow escaped scholarly consideration. Why have previous art historians not concerned themselves with quitters? And how does the long-term cultural and economic history of the United States relate to this aversion? This suite of essays considers multiple answers to these questions, arguing that it is far too simple to say that the history of American art is a history of and by those who persevered, let alone of those who triumphed. At the same time, the lack of discussion of “ex-artists” by historians of American art reflects inherited cultural biases best thrown into relief by considering the topic comparatively and over the longue durée.

§

From John Henry’s relentless hammer and Paul Bunyan’s legendary endurance to Benjamin Franklin’s adages in “The Way to Wealth,” the place of hard work in both the history and mythology of the United States is so unavoidable as to be cliché. It should come as no surprise, then, that it has taken some time for quitting to attract art-historical attention, and all the more so for historians of American art. After all, for the original European settlers of a continent turned colony, determination and persistence were overdetermined aspects of their identity-defining labor, which was disproportionately agricultural and which made them “the chosen people of God,” to use Thomas Jefferson’s infamous formulation.2 Little wonder, then, that anecdotes recapitulating this message have been frequently expressed by US American authors and continue to be passed down to subsequent generations. Workism, a pejorative neologism coined by podcaster and journalist Derek Thompson in 2019 to refer to “the belief that work is not only necessary to economic production, but also the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose,” demonstrates the enduring nature of these ideas.3 Art-historical correlates of them are also commonplace: think of Charles Willson Peale’s entrepreneurial productivity or Gutzon Borglum’s monumental sculptures. The central place of the Protestant work ethic in the Euro-American imagination has long made quitting seem decidedly un-American.

The history of US American art has surely been written against this broad background, and briefly considering some moments from its codification adds weight to the above associations. Just as it is no secret, for instance, that early histories of American art, like those written by William Dunlap, disproportionately focus on men, so too is it no coincidence that Euro-American men have long been born and raised to work. By lionizing and canonizing male artists, historians like Dunlap leaned into their nineteenth-century cultural biases, thereby lending credibility to the histories they were writing.4 Such dynamics were arguably all the more important in Dunlap’s rapidly industrializing and gradually secularizing world, wherein religion was slowly losing hold on Euro-American culture. Dunlap’s hagiographic focus on hardworking men simply followed suit, helping to fill the cultural void.

During the twentieth century, such dynamics became all the more overdetermined when the historiography of US American art—in contradistinction to the physical creation of that art—itself became highly professionalized. As Michael Leja notes, this development is remarkably recent and significantly stems from the funding efforts of a handful of foundations—notably the Luce, Wyeth, and Terra foundations—which only started in the 1980s. Before the financial commitments of these philanthropic organizations entered the budget cycles of higher education, “few universities with graduate programs in art history had faculty specializing in this field,”5 which, as Wanda Corn remembers, had the status of an “impoverished, unwanted stepchild of art history.”6 The requisite money to professionalize American art studies, however, needless to say did more than create extensive new knowledge; it also created a new generation of “Americanist” art historians who were part of a “professional managerial class.”7 Such scholars launched careers of their own, which, for better or worse, were bound to the fortunes of the reputations of the artists they studied. It hardly takes a leap of the imagination to recognize that this financial reality brought a bias against quitters—against economic failure—with it. It also made trends in scholarship all the more acute as they were literally invested with financial value.

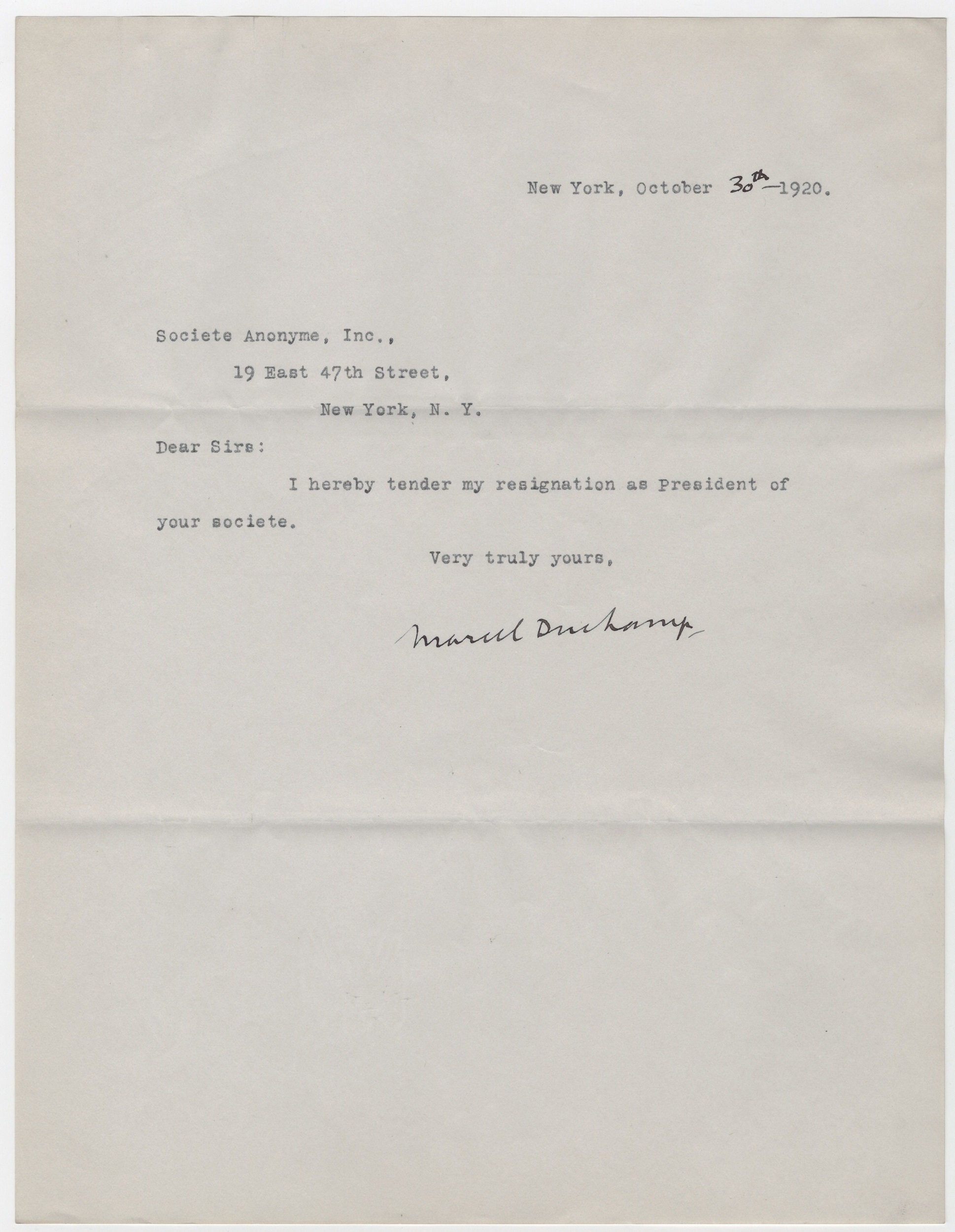

Duchamp’s historical position between these two paradigms of artistic practice makes him a linchpin between the forms of quitting considered in the following essays. On the one hand, Samuel F. B. Morse and William James Stillman—analyzed by Paul Staiti and Diana Strazdes, respectively—embody nineteenth-century figures who quit art by forsaking their physical fabrication of it. Morse and Stillman abandoned art, in other words, as one would expect for a profession so associated with the production of “objects.” That many art historians still today ground their research and pedagogy on “object-based analysis” speaks to how necessary this outmoded understanding of visual art remains.10 On the other hand, Lee Lozano and Tehching Hsieh—contextualized by Chloe Julius and Tom Day—embody post-1960s artists who quit art on a decidedly conceptual level: quitting, in fact, is intimately entangled with their professional artistic practices and personas, meaning that they performed quitting much like Duchamp before them. Whereas it is tempting to divide the lives of Morse and Stillman between their careers as object makers and ex-object makers, the lives of Hsieh and Lozano lack comparable demarcations.

The difficulties that these postwar ex-artists embody, of course, also dramatize how the dichotomy between the physical and the conceptual that has come to define the artistic shift foreshadowed by Duchamp’s precedent was only ever partial. Just as it is self-evident that considerable conceptual work was required to produce Morse’s and Stillman’s paintings, so too is it obvious that some form of physical production—however minimal—was a necessary dimension to Hsieh’s and Lozano’s practices. Nevertheless, the difference between these two groups of ex-artists is evident enough and neatly embodies the conventionally understood transformation of visual art from a traditionally “physical” to a radically “conceptual” activity. When considered through the lens of the ex-artist, such a well-worn story also raises some specific questions. For example, how concerned can and should art historians be with the work that ex-artists like Morse and Stillman pursued after they gave up on art as it was traditionally conceived? And conversely, as ex-artists, should the more traditional or physical artistic production of figures like Hsieh and Lozano always be teleologically anchored to the more radical, dematerialized acts of refusal that they pursued? Answers to these questions can begin to reveal some of the very biases in the history of American art that have largely excluded quitters from consideration.

For instance, in relation to the first question about Morse and Stillman, it has long been tempting to connect Morse’s early work as a painter to his later work as an inventor.11 On such a reading, Morse’s great invention of the electromagnetic telegraph is somehow latent within his early practice as an artist. Considering the prominent place that scholars such as Pamela H. Smith have given to the power of artistic know-how in the history of science, such a thesis would be common enough today and welcome by many.12 The processes of artistic fabrication and the processes of scientific discovery, so this tradition of scholarship contends, complement each other. The same thesis, however, also risks a kind of triumphant individualism, wherein the epistemological potential of Morse’s early craft-based production somehow—even unwittingly—played itself out in his later achievements. Through such an argument, Morse is positioned as having merely pivoted in his career rather than truly quit, because an evident connection within his professional transition from artist to inventor is identified.

If understandable and even defensible, the entrepreneurialism implicit within such a thesis is arguably one of the very stereotypes of American culture that discourages the historical consideration of ex-artists in the first place. Indeed, one of the reasons why art historians are less prone to consider the later work of Morse—or the work of any other figure who began their life with some form of artistic training only not to become a professionally successful artist—is ostensibly that the success of that later work is premised on the abandonment of the profession that art historians are pledged to defend. The success of art historians as art historians, in other words, is premised on the success of artists as artists, which makes the idea that an art historian would start studying a prominent intellectual like William James—who trained as an artist in his youth before becoming the generation-defining psychologist and philosopher known today—would be somehow perverse.13 But what if demonstrating the full value of art requires pursuing its successful afterlives elsewhere? However commonplace, if correct, such a thesis would mean that research into ex-artists is not just desirable but actually fundamental to art history.

In relation to the second set of questions about Hsieh and Lozano, reading their more traditional or conventional artistic production in relation to their more dramatic acts of quitting risks a similarly triumphant story. Yet in their cases, quitting does more than follow through on what avant-gardists would surely identify as the radically disruptive potential of their earlier practices. By making quitting into a performance, these artists also blurred the boundaries between their art and their lives to such an extent that it becomes unclear if they ever truly quit art, if they ever really got off the proverbial artistic stage. Much as Duchamp’s practice gained interest in the age of Fluxus, Hsieh’s and Lozano’s performative quitting has taken on special relevance in our age of social media. As the artist and writer Jenny Odell laments in a 2017 YouTube speech that went viral, “Every waking moment has become pertinent to making a living.”14 The present world is defined by almost constant connectivity, and the ever-more-knotted entanglement of our economic and personal states of affairs has become, for many at least, oppressive. This general condition also stands behind the recent vogue of “quiet quitting,” the decision to perform only the bare minimum of required work. Micro acts of resistance like these are ways to reestablish boundaries around work, which, of course, for a professional artist is the line between art and life. If we as art historians have long been prone to celebrate the blurring of that boundary, Duchamp, it would seem, at least partially, recognized its danger. When confronted with the “manual servitude of the artist,” after all, he insisted on earning his living as a librarian.15

Faced as we are today with concerns over professional boundaries, a fitting conclusion comes from a recent New York Times article that announces the end of the “Great Resignation.” Recounting an episode that is very much a part of the expanded history of American art, the article tells the story of Aubrey Moya, a photographer based in Fort Worth, Texas, who “joined the Great Resignation” in order “to start the photography business” that was her dream.16 The pursuit of such a passion project should be celebrated, and I refer to it here partially to do so. At the same time, however, passions are inevitably personal, thereby risking the very conflation of art and life that the history of ex-artists in America warns against. “The cost of a thing,” Thoreau once wrote, “is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.”17 In our age of political division and historic inequality, of social media and perpetual connectivity, perhaps it is again time for historians of American art—or for all art historians for that matter—to return to thinking about art in similarly basic terms: as a means toward an economic end.

Cite this article: C. Oliver O’Donnell, introduction to “Ex-Artists in America,” In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18909.

Notes

- Inspiration for this project has come from three public-facing articles in particular: Adam Phillips, “On Giving Up,” London Review of Books 44, no.1 (January 6, 2022), https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v44/n01/adam-phillips/on-giving-up; Cal Newport, “The Year in Quiet Quitting,” New Yorker, December 29, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/2022-in-review/the-year-in-quiet-quitting; and Derek Thompson, “Workism Is Making Americans Miserable,” Atlantic, February 24, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/02/religion-workism-making-americans-miserable/583441. ↵

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the States of Virginia, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955), 164–65. ↵

- Derek Thompson, On Work: Money, Meaning, Identity (New York: Atlantic Editions, 2023), 35. ↵

- William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States (New York: George Scott, 1834). ↵

- Michael Leja, “Foundations of American Art Scholarship,” Perspective 2 (2015), http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/6045. ↵

- Wanda Corn, “Coming of Age: Historical Scholarship in American Art,” Art Bulletin 70, no. 2 (June 1988): 188. ↵

- See John and Barbara Ehrenreich, “The Professional-Managerial Class,” Radical America 11, no. 2 (March–April 1977): 7–32. ↵

- Elena Filipovic, The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 4. ↵

- Richard Wollheim, “Minimal Art,” in Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Gregory Battcock (New York: Dutton, 1968), 387–99. ↵

- This term is frequently found on museum websites and in scholarship. For instance, Kathleen A. Foster, “Looking for Thomas Eakins: The Lure of the Archive and the Object,” in A Companion to American Art, ed. John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill, and Jason D. LaFountain (Chincester: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), 146–64. ↵

- For instance, Jean-Philippe Antoine, “Inscribing Information, Inscribing Memories: Morse, Gallery of the Louvre, and the Electromagnetic Telegraph,” in Samuel F. B. Morse’s “Gallery of the Louvre” and the Art of Invention, ed. Peter John Brownlee (Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2014), 110–29. ↵

- Pamela H. Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). ↵

- Though the surviving corpus of artworks made by William James has been studied and even published, it has not attracted art-historical attention and seemingly remains of interest only to intellectual historians. For an example of how some of James’s drawings have been interpreted, see Maria Helena P. T. Machado, ed., Brazil through the Eyes of William James: Letters, Diaries, and Drawings, 1865–1866 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006). ↵

- Jenny Odell, “How to Do Nothing,” The Conference, organized by Media Evolution, June 30, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNRqswoCVcM, at 25:36. ↵

- Marcel Duchamp, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, ed. Pierre Cabanne (New York: Da Capo, 1987), 41. ↵

- Ben Casselman, “The ‘Great Resignation’ Is Over,” New York Times, July 6, 2023. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854; Philadelphia: Henry Altemus, 1909), 37. ↵

About the Author(s): C. Oliver O’Donnell is an Associate Lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art and an Associate Fellow at the Warburg Institute, University of London.