Lee Lozano’s Revolution, or Quitting Art at the End of the 1960s

PDF: Julius, Lee Lozano’s Revolution

The new object of art is not yet “given,” but the familiar object has become impossible, false.

—Herbert Marcuse1

The art of Lee Lozano (1930–1999) took a conceptual turn in the late 1960s. Replacing painting and drawing with what she called “pieces,” Lozano embarked on a series of works whose form was structured by a command: stay high all day (Grass Piece, 1969), abstain from staying high (No-Grass Piece, 1969), talk with other artists (Dialogue Piece, 1969), or masturbate every day and take notes (Masturbation Investigation, 1969).2 These pieces—along with the others in the series—were all written up in Lozano’s notebooks, forming a textual residue for an art that necessarily existed beyond the page. Rather than produce an object, these pieces turned art into an objective. Hence “life-art,” the term Lozano used to describe her conceptual practice; this was an art to be lived, not objectified.3

The most enigmatic and conceptually knotty of her life-art works was Dropout Piece. Described by Lozano as “the hardest work I have ever done,” Dropout Piece formalized her status as an ex-artist.4 While it was first mentioned in Lozano’s notebook in an entry dated April 5, 1970, Dropout Piece grew out of her earlier work General Strike Piece, begun a year prior, on February 8, 1969. Both pieces called for a withdrawal from work, although the latter imperative would prove more conclusive. In what follows, I emphasize the late-1960s beginnings of Lozano’s two withdrawals. There, I argue, in the dying embers of the New Left, lie the unique historical conditions that gave shape to this particular instance of an artist quitting art.

The line between General Strike Piece and Dropout Piece is far from straightforward. While the seed for the later work was sown in the former, dropping out was by no means an inevitability when Lozano embarked on her strike. Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer’s characterization of General Strike Piece as “proto-dropout” gestures toward this contingency.5 Anticipatory but not yet fully formed, “proto” allows us to think about these two pieces in a sequence that could have been otherwise. It also reminds us of a key distinction between the two pieces. Striking is, of course, quite different from dropping out, especially—as was the case with Lozano—when that dropout is permanent. At stake is a question of means and ends. Whereas in a strike, withdrawal is enacted in pursuit of an aim, in a dropout, withdrawal is the aim. As such, General Strike Piece anticipated Dropout Piece inasmuch as it called for the same action (or, to be more precise, inaction), but whereas Lozano’s strike was carried out “in order to pursue investigation of total personal & public revolution,” her dropout was carried out with no discernible aim.6 Into this matrix of withdrawals, a third should be added: Lozano’s boycott of women. Boycotts, like strikes, usually involve aims, and Lozano’s 1971 boycott was conducted in the hope that it might improve her communication with women—but this resolution never came to pass. In its permanence, therefore, Lozano’s boycott ended up sharing a greater affinity with her dropout—neither women nor work figured in Lozano’s life after the 1960s.7 Whether or not this means Dropout Piece endured as an artwork until her death in 1998 is a question best left open.

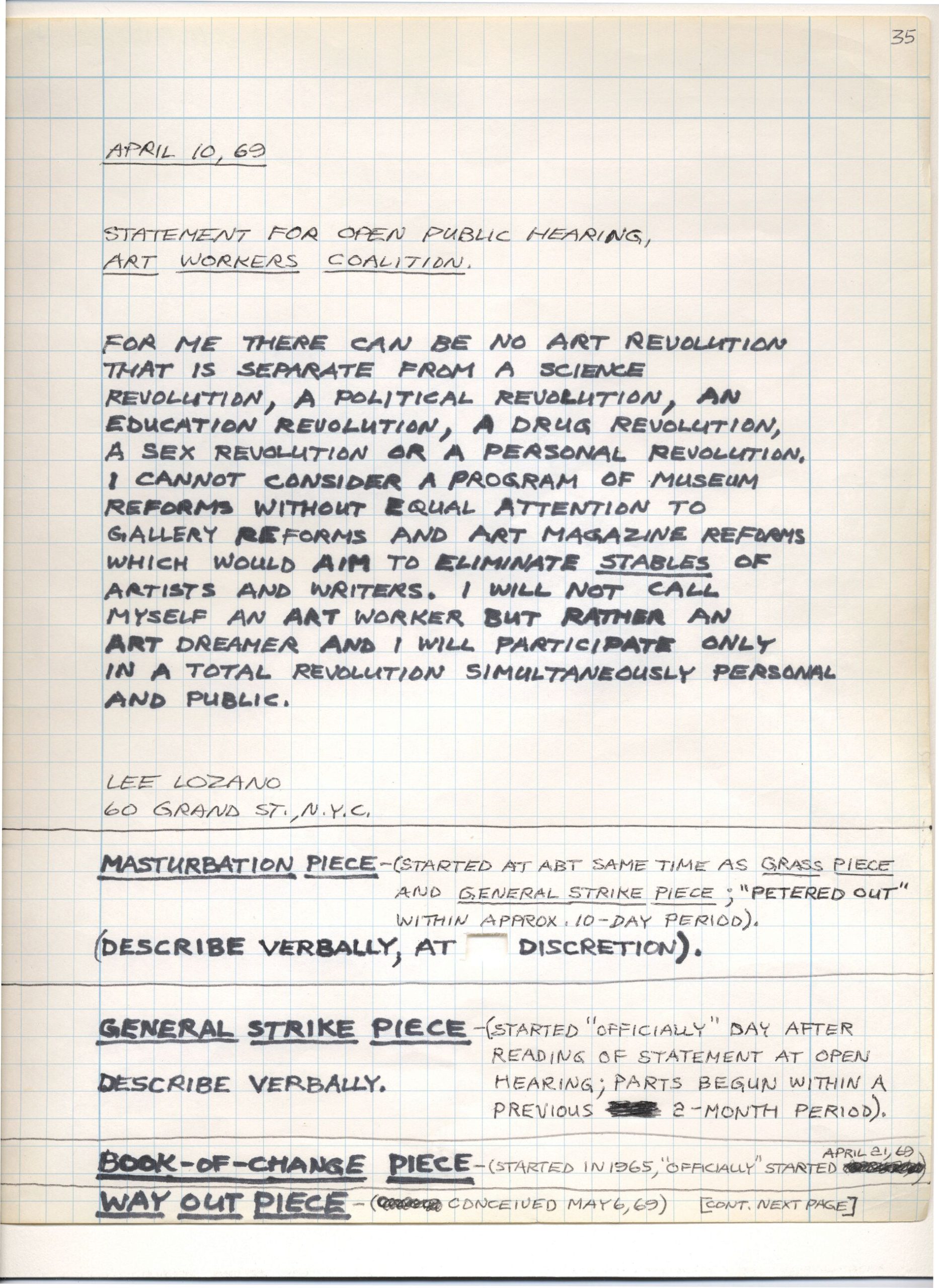

Open-endedness does not foreclose a beginning, and Lozano’s various withdrawals must be set within their original context. In the case of General Strike Piece and Dialogue Piece, these conceptualizations of not working express certain attitudes about art and labor that formed as the 1960s moved into the 1970s. Conceived in 1969 and 1970 respectively, the two pieces bookend this decadal shift, and while chronological periodization only takes us so far, it is notable that revolution fell out of the picture when the second work came around. Revolution was invoked twice in relation to General Strike Piece: first, in the abovementioned already-cited entry in Lozano’s journal; and second, at an open hearing of the newly established Artist Workers’ Coalition (AWC) at the School of Visual Arts in New York, on April 10, 1969, where Lozano first publicly announced the work (fig. 1). Raising revolution in this post-1968 moment was decidedly provocative, even (or perhaps especially) within the radical New York art world circles within which Lozano moved. While strikes in the United States would reach a postwar high in 1970, at the time of the open hearing, the revolutionary promise of the New Left was fast receding. By embedding her strike within the language of revolution, Lozano’s General Strike Piece simultaneously looked back to the 1960s and ahead to the 1970s. Conversely, in relinquishing the revolutionary promise of the 1960s, Dropout Piece appears less untimely.

Whereas Lozano’s write-up of General Strike Piece only obliquely referred to “total personal & public revolution,” her statement at the open hearing elaborated on what that revolution might entail. Contrary to the views of the event’s organizers, Lozano’s revolution required rejecting the term “art worker.” Indeed, for Lozano, the term “ex–art worker” feels more fitting than “ex-artist.” Her withdrawal from making art was made at a time when the issue of artistic labor had come to the foreground. Rather than improve her working conditions, however, Lozano simply refused to work. Her antagonism toward the term “art worker” was spelled out in her remarks, which responded to the prompt, “What should be the program of the art workers regarding museum reform and to establish the program of the art workers coalition?”8 Lozano’s statement is worth quoting in full:

For me there can be no art revolution that is separate from a science revolution, a political revolution, an education revolution, a drug revolution, a sex revolution or a personal revolution. I cannot consider a program of museum reforms without equal attention to gallery reforms and art magazine reforms which would aim to eliminate stables of artists and writers. I will not call myself an art worker but rather an art dreamer and I will participate only in a total revolution simultaneously personal and public.9

Baldly refusing every single premise on which the initial prompt had been staked, this statement made it quite clear that General Strike Piece had nothing to do with the AWC. They were her audience, not her collaborators. In her strike, the AWC was as much a target as the museums. The AWC had not put revolution on the table, but if they had, it would have likely been as an art revolution, not the “total revolution” Lozano demanded. Worse, Lozano accused the AWC of not being “total” enough in their dealings with art by neglecting to mention galleries or art magazines. But the real sucker punch was Lozano’s final line. By rejecting the term “art worker” in favor of “art dreamer,” Lozano identified the AWC with a certain utilitarianism that stripped their project of its purchase on a new, as-yet-imagined world.

Two months after the open hearing, a letter signed by an unnamed art worker made the rounds in New York. Gauging support for the type of revolution that Lozano had denigrated at the open hearing, the letter implored its readers to “support the Revolution by bringing down our part of the system and clearing the way for change.”10 This letter provided the opening for Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, Julia Bryan-Wilson’s 2009 survey that located the radical potential of American art of the late 1960s and 1970s in its turn toward issues of labor.11 Although sober about the revolutionary promise of replacing artists with art workers, Bryan-Wilson staked that promise here rather than with what she describes as Lozano’s “idiosyncratic” position.”12 Underscoring the gulf between Lozano and her assembled audience at the AWC open hearing, Bryan-Wilson asserted that “Lozano’s denunciation of the term art worker in favor of art dreamer signals a model of individual rather than collective transformation.”13

That Lozano’s revolution tended inward, despite her claims that it was both personal and public, is a frequent critique leveled at General Strike Piece. Given that what followed was her Dropout Piece—and not “total revolution”—such critiques are understandable. For example, when comparing Lozano’s General Strike Piece to Adrian Piper’s contemporaneous decision to withdraw her work from a group exhibition at the New York Cultural Centre, Jo Applin posited:

While Piper’s gesture was strategic and political, Lozano’s withdrawal and general strike at best hurt only herself and, at worst, signaled a solipsism and emphasis on individuality and personal freedom that was out of kilter with a contemporary politics of participation and collective empowerment.14

Considering what was to come, “out of kilter” is certainly right. While Lozano’s revolution never arrived, the ascent of the women’s movement threw her politics of nonparticipation into sharp relief. Even without her boycott of women, in the context of the 1970s’ consciousness-raising, collective action, and community building, Lozano’s withdrawal appears as a cynical inversion of the feminist battle cry that the personal is political.

Applin used the term “proto-feminist” to deal with this issue, not to shy away from Lozano’s antagonistic relationship to the nascent women’s movement but rather to frame her work as anticipatory of certain questions around subjectivity, sexuality, and agency that were posed anew under the banner of second-wave feminism.15 Yet rather than read the 1970s back into Lozano’s late 1960s work, these pieces can also be illuminated by the politics of their time. While Lozano’s revolution was certainly out of step with second-wave feminist politics, it did chime with what Herbert Marcuse called the “Great Refusal” in his 1969 book Essay on Liberation. Less of a program and more of a diagnosis, Marcuse’s essay offered an extended analysis on why the American New Left—Marcuse’s primary audience—might reject “the rules of the game that is rigged against them.”16 Marcuse exerted a particular influence on that corner of the New Left characterized by Bryan-Wilson as the “New York art left,” and something of his Great Refusal can certainly be detected in the flight of artists like Agnes Martin, Lee Bontecou, and Michael Heizer from the New York gallery system.17 Avowedly political, at least in its expression in General Strike Piece, Lozano’s own Great Refusal resonated with many of the observations in Marcuse’s Essay on Liberation. Note the strong echo of her AWC statement in his proposal that

the artificial and “private” liberation anticipates, in a distorted manner, an exigency of the social liberation: the revolution must be at the same time a revolution in perception which will accompany the material and intellectual reconstruction of society, creating the new aesthetic environment.18

Part of Marcuse’s appeal as a political philosopher among artists was his sustained engagement with art, attested here in his interlinking of “revolution” with a “new aesthetic environment.” It calls to mind the painter David Reed’s astute observation that for Lozano, the AWC “weren’t radical enough for her, in that they weren’t artistic enough. She wanted the two things to come together—a very difficult position to sustain.”19

For Lozano—at least in 1969—conceptual art brought those two things together. By dematerializing art, rendering it a “piece” rather than an “object,” it could be liberated only to circulate within the world of ideas. On this point, Marcuse was in agreement; the promise of “dematerialization” is discussed in his Essay on Liberation.20 After the 1960s, that promise ran out of steam. Lucy Lippard, the feminist critic and curator who was deeply attuned to the politics of conceptual art, later reflected that “with hindsight, it is clear they [conceptual artists] could have run further.”21 Another critic who felt this disappointment was Barbara Rose, who in 1969 had hypothesized that what she called “non-objective art” permitted “non-cooperation” with a broken art-world system and thus could be seen as “the aesthetic equivalent of the wholesale refusal of the young to participate in compromised situations (e.g. the Vietnam War).”22 Rose would give up on nonobjective art long before Lippard, and she devoted much of her art criticism in the 1970s to showing that it had ultimately lead to a dead end. Object or no object, Rose argued, the dependence of dematerialized art on an audience meant institutionalization could only be deferred, never avoided.23

Refusing to participate is different from dropping out, which returns us to the key distinction between General Strike Piece and Dropout Piece. If the earlier work can be aligned with the late New Left politics of nonparticipation and Marcuse’s Great Refusal, the latter fits more comfortably with the decidedly apolitical message of “Turn on, Tune in, Drop out,” the title of psychologist Timothy Leary’s famous broadcast. Although delivered in 1966, the persistent legibility of Leary’s message attests to the ease with which it assimilated into the post-1968 world in which we still live. Far less legible, however, is the genuine revolutionary potential conferred to nonparticipation during this period. Thus, while General Strike Piece and Dropout Piece share too many similarities to be entirely decoupled from each other, Lozano’s movement from a strike to a dropout does point toward the diminishing political horizons in which art was made—and not made—in post-1968 America. Helen Molesworth, in an article on Lozano that notably invokes Leary’s formulation in its title, posited that “her refusal to play by the rules feels simultaneously utterly pathological and consummately idealistic.”24 Lozano’s idealism and her utopianism are a constant refrain throughout the scholarship, two words that tacitly acknowledge both the politics of her art and the failure of those politics to materialize. Much harder to acknowledge, however, is Lozano’s realism, the possibility that her General Strike Piece—and the New Left politics that motivated it—might have actually led to revolution and not just a dropout. Over fifty years later, that possibility is even harder to grasp, especially as the game whose rules Lozano refused to follow is still being played. Yet if we can hold onto the idea that Lozano’s revolution was genuinely plausible, the political stakes of her decision to quit art can come back into view.

Cite this article: Chloë Julius, “Lee Lozano’s Revolution, or Quitting Art at the End of the 1960s,” in “Ex-Artists in America,” ed. Oliver O’Donnell, In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18927.

Notes

- Herbert Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation (London: Allen Lane, Penguin Press, 1969), 38. ↵

- Lozano’s choice of the term “piece” to describe these artworks was quite deliberate and entirely in step with the expanded field of late-1960s American art. It permitted not only a rejection of the division of art into different media but also of the category of art itself. ↵

- Given how Lozano’s life-art seems to jar with the received view of conceptual art as dry, disinterested, and depersonalized, Lucy Lippard’s elucidation of Lozano’s conceptualism is helpful here: “Unlike most ‘instruction’ or ‘command’ pieces, for example, Lozano’s are directed to herself, and she has carried them out scrupulously, no matter how difficult to sustain that may be. Her art, it has been said, becomes the means by which to transform her life, and, by implication, the lives of others and of the planet itself”; in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 98. ↵

- Lee Lozano, “Private Notebook 8,” April 5, 1970, 114. The Estate of Lee Lozano, courtesy Hauser & Wirth. ↵

- Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Lee Lozano: Dropout Piece (London: Afterall, 2014), 15. ↵

- This text is part Lee Lozano’s General Strike Piece, documentation of which is held at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. Jo Applin also underscores the distinction between the terms “strike” and “dropout” as they relate to Lozano’s practice in Lee Lozano: Not Working (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 150. Writing in a similar direction, Helen Molesworth roots Lozano’s pre-dropout terms in the language of 1960s politics: “Lozano’s use of words like ‘boycott’ and ‘strike’ evoke the Civil Rights Movement’s strategies of refusal to participate in systems deemed inequitable”; in “Tune in, Turn on, Drop out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano,” Art Journal (Winter 2002): 70. ↵

- Applin, Lee Lozano, 17. ↵

- Art Workers’ Coalition, Open Hearing (New York: School of the Visual Arts, 1969), n.p., on Primary Information, accessed April 24, 2024, https://primaryinformation.org/files/FOH.pdf. ↵

- Lee Lozano, “Statement for Open Public Hearing, Art Workers’ Coalition,” in sec. 38, n.p. ↵

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical practice in the Vietnam War Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 1. ↵

- Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers, 1. ↵

- Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers, 17. ↵

- Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers, 18. ↵

- Applin, Lee Lozano, 137. ↵

- See Applin, Lee Lozano, 22, 29, 123, 47. ↵

- Marcuse, Essay on Liberation, 6. ↵

- Lehrer-Graiwer provides a good survey of this trend, which extended into the 1970s and also included artists like Jo Baer, Christine Kozlov, and Elaine Sturtevant; in Lee Lozano, 15. Regarding the “New York art left”, Bryan-Wilson also points to Robert Morris’s direct application of Marcuse’s theories in his “Art Strike” from 1970; in Art Workers, 118. ↵

- Marcuse, Essay on Liberation, 37. ↵

- David Reed and Katy Siegel, “Making Waves: The Legacy of Lee Lozano,” Artforum 40, no. 2 (October 2001), https://www.artforum.com/features/making-waves-the-legacy-of-lee-lozano-163061. ↵

- Marcuse, Essay on Liberation, 49. ↵

- Lippard, Six Years, i. In another reflective article, this time considering the legacy of conceptual curating, Lippard framed this situation even more baldly: “The sum of the parts would add up to permanent political change. . . . The fact that it has not signals an ultimate failure,” in “Curating by Numbers,” Tate Papers 12 (2009): 6. ↵

- Barbara Rose, “The Politics of Art: Part III” (1969), in Autocritique: Essays on Art and Anti-Art (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987), 241. ↵

- See, for example, Barbara Rose, “Document of an Age” (1972), in Autocritique, 253–55; and Barbara Rose, “Twilight of the Superstars” (1974), in Autocritique, 263–72. ↵

- Molesworth, “Tune in, Turn on, Drop out,” 71. ↵

About the Author(s): Chloë Julius is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Nottingham.