“No Art” Protests: Restricting and Withdrawing Artistic Labor Downtown

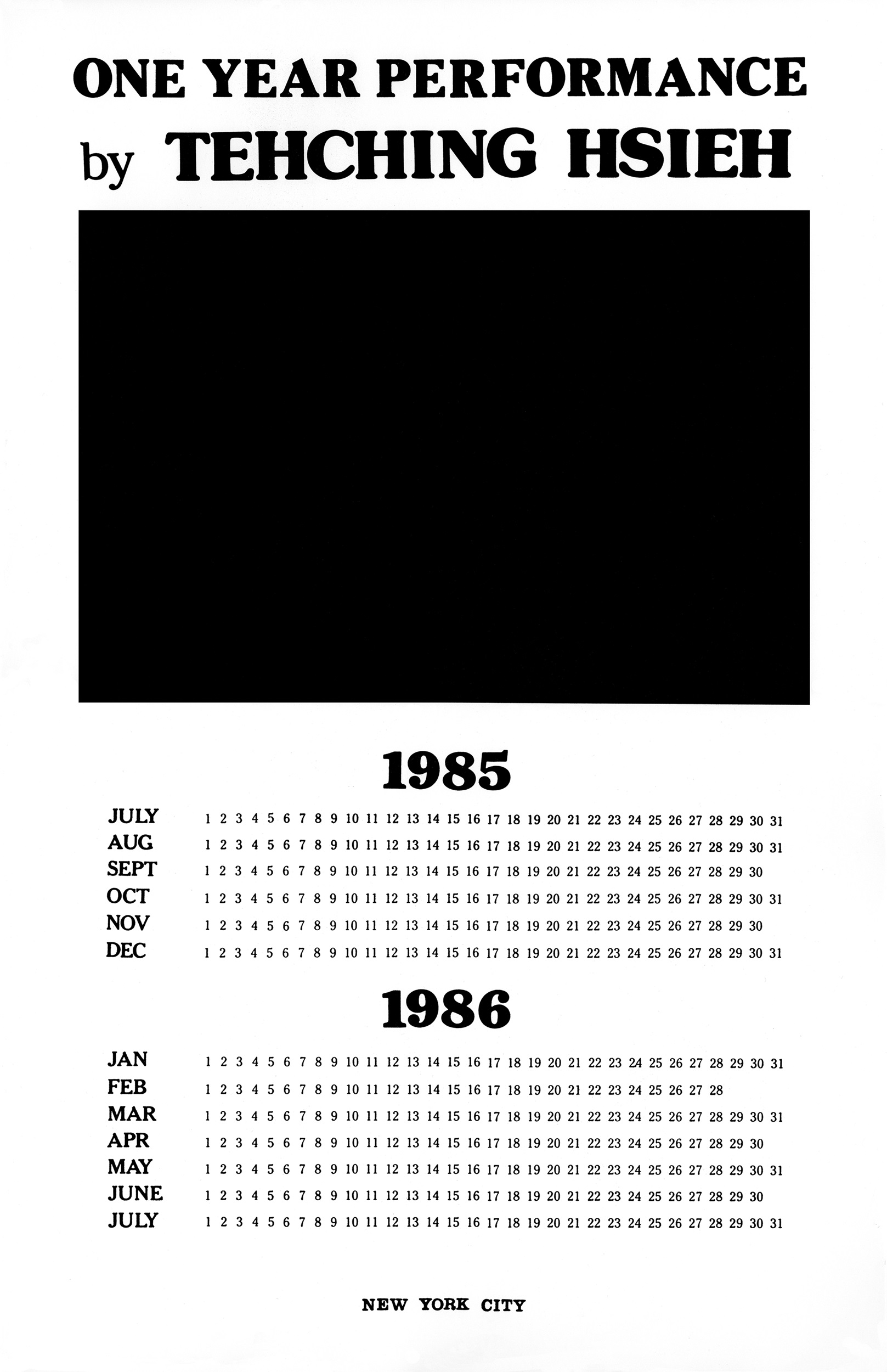

For one year in the mid-1980s, the Taiwanese-American artist and pioneer of durational performance Tehching Hsieh (b. 1950) removed himself from the practice, machinations, and expectations of art, turning away from its ecosystem and even his own consumption of it. His Life-Work, as Hsieh’s performance works are collectively called, include One Year Performance, 1985–1986 (No Art Piece). The work is evidenced by a signed, partially redacted statement and poster-style annual calendar (figs. 1, 2). It was the penultimate long-form performance in a series of lengthy works by Hsieh, in which he submitted his body to various rigors, restrictions, and refusals. These include a year spent living in a cage, a year punching a time clock every hour, a year being tethered to fellow artist Linda Montano, and a year spent living outdoors.1 Unlike the other works in this series, No Art Piece and his subsequent work, Thirteen Year Plan (1986–99) (in which Hsieh removed himself from the art world and claimed to make artworks but not to display or exhibit them in any context) were performances with no verifiable or traceable content. They involved a refusal of labor but also a refusal of documentation or ephemera that might paradoxically stand in for the inactivity of the work. As such, Thirteen Year Plan is troubling to examine and has elicited very little commentary from scholars. Here I want to offer a possible reading of Hsieh’s work as partaking in a wider cultural expression of art stoppages or art strikes that are difficult to disentangle from the politically active context in which the work was conceived and performed.

To this end, I will begin with a brief overview of the diverse history of “no art” protests and actions by artists and art collectives in post-1960 downtown New York, especially in relation to artists’ housing, the Vietnam War, and the AIDS crisis. Partially withholding or outright withdrawing art to protest living conditions; to express dissent against local and federal government policies; or to condemn inaction on social issues, including housing, war, racial and gender equality, and public health crises has a rich history and forms a strain of activist-oriented performance-protest in the city. Against the backdrop of this tradition, I turn to Hsieh’s performance of refusal in One Year Performance, 1985–1986 (No Art Piece). Focusing on the scant material and administrative traces of the event, I read Hsieh’s refusal to participate in the art world of 1980s New York in the context of the neoliberal gentrification that quickly overtook the art spaces of SoHo and the Lower East Side. Because Hsieh’s performance can only partially be situated within this tradition, however, I additionally locate No Art Piece as being indebted to the activities of Henry Flynt (b. 1940), an anti-art figure who chose to cease participation in the art world in the 1960s to instead pursue his own version of cultural life. While Hsieh’s (non)performance does not explicitly wed itself to any direct or distinct political cause, its general rejection of the art world strongly resonates with Flynt’s own refusal of the art world, which was based on his understanding of it as an inherently problematic construction that serves to propagate entrenched classed and racialized hierarchies. Ultimately this essay presents the refusal of making artwork by artists as a kind of radical agency—a tool in their arsenal to help further a committed political radicalism, one that might disentangle or even emancipate art from work and life itself.

Years of Refusal

Unlike some other prominent postwar artists who have conceptually, performatively, or permanently dropped out of the art world (though how fulsome this self-imposed removal is varies from case to case), Hsieh’s exit was only ever conceived as a temporary imposition. By now there is substantial literature on figures such as Lee Lozano (explored by Chloe Julius in this issue’s In The Round) and Charlotte Posenenske, who are pegged as having dropped out of the art world because of its political inadequacies and ineffective posturing in increasingly turbulent times. Posenenske claimed, in a statement published in May 1968, that

though art’s formal development has progressed at an increasing tempo, its social function has regressed. Art is a commodity of transient contemporary significance, yet the market is tiny, and prestige and prices rise the less relevant the supply is. It is difficult for me to come to terms with the fact that art can contribute nothing to solving urgent social problems.2

Using less dryly analytical wording, Lozano included a note on her self-imposed, gradual removal from the art world on one of her scores of Language Pieces in a work called General Strike Piece (1969), which preceded her Drop Out Piece (1970).3 Her terms of removal are expressed in this radically political and vague tirade:

GRADUALLY BUT DETERMINEDLY AVOID BEING PRESENT AT OFFICIAL OR PUBLIC ‘UPTOWN’ FUNCTIONS OR GATHERINGS RELATED TO THE ‘ART WORLD’ IN ORDER TO PURSUE INVESTIGATION OF TOTAL PERSONAL & PUBLIC REVOLUTION.

Two things distinguish Hsieh’s work from these canonical examples of “no art” protest. First, the artist has never provided an explicit statement offering a reason, political or otherwise, for removing or withholding artworks. Second, despite its length, No Art Piece was only a temporary cessation of work. It was not a “drop out,” which is an act, as art historian Jo Applin writes, that is “often classed as the least political action an individual can undertake.”4 Hsieh’s temporary removal implies a relationship to more pointed critique and invokes a specific history. As such I will consider the work in relation to the politics of the art strike, a mode of protest that has a storied history in post-1960 US American art practice. Hsieh’s performances have been considered by scholars from a variety of perspectives, including the study of law, in particular the dictates and doctrines of legal contacts; the maturation of the carceral, domestically militarized prison-industrial world of “punitive America”; and the status and experience of both unhoused individuals and migrants.5 No Art Piece, however, also sits uneasily with such specific readings; Hsieh sees the work as an expression of one of the central concerns of his One Year Performances, as a confrontation with time itself.

Speaking with the historian Adrian Heathfield, Hsieh contextualized the work in relation to preceding examples:

This “No art piece” would have happened sooner or later, although it happened too quickly to be accepted by the art world at that moment, it was a new dilemma I had to face, also a necessary stage I had to pass. Since the concept of my work is passing time, not about how to pass time, I had to give this piece an equalised position, place it within the series of One Year Performances. There is no accurate rule formulated in this piece; the rule cannot give this piece powerful support, it is just used for distinguishing life and art.6

Here Hsieh offers clear insight on one of the key aspects of his work that is pertinent to No Art Piece: namely that he is only imposing an arbitrary rule or instruction for the performance—that he will not engage with art in any way for a determined period of time—as a way to remove art from life, as if the cultural conditions and contexts of artistic production are in and of themselves a kind of bad object that needs to be expunged.

For performance historian Joshua Chambers Letson, Hsieh’s work explores “the regime of work and the power of withdrawal” more broadly. Hsieh performs an “unworking of work” that “offers us a means for affecting (or at least imagining) an undoing of the regime of work” and shows “a practice of withdrawal that may allow the performing subject to survive, if not sublimate, work’s claim to the body.”7 For Chambers Letson, therefore, the resonances of these works cannot be separated from Hsieh’s own subject position at the time as an illegal migrant living in the United States, and as such, his work continues to prompt questions that are of “critical importance to the conjoined struggles for the survival and emancipation of immigrants, refugees, and people of color, who live and work in hostile environments across Europe and the United States at our present historical juncture.”8

Hsieh’s performative refusals of the art world, then, can be mapped onto thinking about large themes that remain relevant and project into our own contemporary moment. But I want here to think more specifically about the context in which this work was created, its immediate predecessors, and the potential meanings of leaving the work world behind and refusing the labor of artwork specifically.

Art stoppage as a means of dissent has been well documented, especially the activities of the so called “art left” of the 1960s, who were organizing protests against the war in Vietnam (both the conflict itself and the suppression of domestic antiwar activity). Singled out in particular are groups like the Art Workers Coalition and its offshoot organization, New York Art Strike Against War, Racism, and Repression, which orchestrated the New York Art Strike in the spring of 1970. Scholarship has perhaps most remarked upon its activities to shut down museums, with the ambivalent relationship of Art Strike’s co-chair Robert Morris with the symbolism of working-class politics, Morris’s own artistic labor, and his organizational posturing making for a particularly charged combination that has attracted astute analysis.9

The idea of art striking in New York, however, has a longer history than this, with the Artist Tenants Association calling on galleries, museums, and studios to close down in early 1964 in order to pressure the city to rezone parts of SoHo to make the buildings more safely inhabitable for artists.10 The act of art refusal also predates Hsieh’s work and has reached wide visibility in the guise of the internationally recognized “Day Without Art,” organized since 1989 by the nonprofit group Visual AIDS to support people living with HIV/AIDS, to enhance relevant pressure campaigns, and to boost funding, research, and support for such initiatives globally.11 Of course, the direct comparison between these efforts and Hsieh’s No Art Piece is not immediately apparent because Hsieh does not tie his act of (non)working to a particular issue that he wishes to confront. His work is instead a way to go about “distinguishing life and art,” as he stated in his interview with Heathfield. It is noteworthy that the work does indeed go on in the vast majority of cases referenced here; tools are downed only for a brief moment before work resumes. Hsieh’s No Art Piece and his follow-up work, Thirteen Year Plan, wherein he supposedly did produce artworks but did not allow them to be seen, escape easy categorization in relation to these art strikes. They perhaps find easier company and share more goals not with the work life of a visual artist but rather with that of the composer and avant-garde impresario who also ceased to produce artworks and instead pursued creative endeavors outside of the art world of New York City: Henry Flynt.

Go in Life

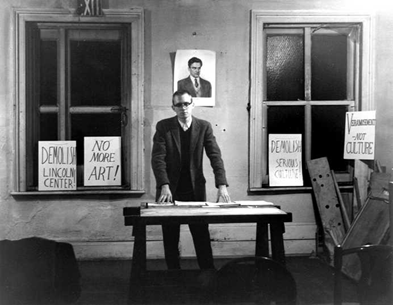

Still living today, Flynt is a Harvard-educated mathematician, philosopher, writer, artist, and musician whose name and anti-art activities pop up in numerous footnotes of studies devoted to the early 1960s avant-garde that circled around LaMonte Young, Tony Conrad, and the early years of the Fluxus group. It was in that group’s foundational publication, Anthology of Chance Operations (1963), that Flynt published his essay “Concept Art,” widely cited as the first use and definition of the term in which artworks’ media was understood as “concepts.”12 A short while after this immersion, he absconded from the New York avant-garde. In one of the few essays exploring the breadth of Flynt’s art and subsequent anti-art career, Michael Oren summarizes:

In 1962 he dissociated himself from the art world to devote himself to writing essays on subjects such as the construction of non-scientific empiricist cognitive modalities, the investigation of experiences of the logically impossible, and the preferability of an individual’s “vera-musement” (later called “brend”) or “just-likings” to oppressive “serious culture.”13

Serious culture, for Flynt, is imperialist, oppressive, and racist. Flynt himself championed Black music and the folk traditions of the poor working-class South, which influenced his own aesthetic as a composer. He saw the staging of new works by towering figures of Western musical experimentalism, like Karlheinz Stockhausen at New York’s Festival of the Avant-Garde (which he picketed in 1964), as examples of high culture that should be resisted, removed, and destroyed. Flynt demonstrated outside concerts and institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art and Lincoln Center, with his compatriots: the artist and musician Tony Conrad, Fluxus founder George Maciunas, and the irascible performance art pioneer and filmmaker Jack Smith. He would later in the 1960s join the Workers of the World, a militant Trotskyist and Maoist group that splintered from the Socialist Workers Party.14 The officialdom of culture is, in Flynt’s eyes, tied to oppressions, occlusions, and dogmas of tradition that are ultimately undergirded by white supremacy. To his mind, high culture conditions viewers and strangulates their ability to embrace culture and life on their own terms. In 1962, he used his distinctive term “brend” for individual “likings” or preferences in culture and life to describe the chokehold of high art:

The conditioning which causes one to venerate “great art” is also a conditioning to dismiss one’s own brend. If one can become aware of one’s brend without the distortion produced by this conditioning one finds that one’s brend is superior to any art, because it has a level of personalization and originality which completely transcends art. . . . If I succeed in getting the individual to recognize his own just-likings, then I will have given him infinitely more than any artist ever can.15

Clearly, for Flynt, the pursuit of one’s own idea and practice of art and culture was something that should be removed from the official functioning of the art world proper. He puts this in starkly leftist, anticapitalistic terms: “Art itself has become an institution which invests waste with legitimacy and even prestige; and it offers instant rewards to people who wish to play the game.”16 It is the game, ultimately, that I think both Flynt and Hsieh were looking to bypass (if not blow up entirely) in order to pursue life work over (art)work. Such resistance to the gamification of the art and cultural sphere are noteworthy in both the context of the 1960s and the 1980s. From the middle of the 1960s, the dematerialization of art and emergence of conceptualism as a new orthodoxy in art practice saw a novel set of opportunities emerge for the marketing and capitalization of increasingly ephemeral artworks.17 To some extent, this was reversed in the 1980s, especially in the downtown East Village scene, which saw the rise of a hypercapitalist and competitive art market predicated on young breakout stars and the re-emergence of painting and sculpture as expensive and highly speculated-upon commodities.18

Hseih’s activities were featured prominently during the 1980s at now-canonical group shows, like Illegal America at Exit Art, and he collaborated with other downtown spaces throughout this period to show and promote his performances. Precisely because of the nonactivity of No Art Piece and Thirteen Year Plan, Hsieh quickly became an obscure figure. During the interview, Heathfield referenced the time that had passed since the conclusion of the self-imposed thirteen-year period of Hsieh’s latest work and asked the artist, “Will you make art again?” Hsieh’s answered, “I haven’t finished my art but I will not do art anymore.”19 This answer would seem an appropriate response from Flynt, who also did not want to see his artistic and cultural life tied up with the art world, its labors, and its classism, which are so dissociated from real life. Hsieh’s implication here is that art can and should be subtracted from the world of “doing,” namely the labor that governs not only its creation but also its exhibition, reception, and consumption. The refusal of “doing” art for Hsieh is not a negation of art but precisely a merging of it with the continuum of his own time on earth outside the art world.

Cite this article: Tom Day, “‘No Art’ Protests: Restricting and Withdrawing Artistic Labor Downtown,” in “Ex-Artists in America,” ed. Oliver O’Donnell, In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18915.

Notes

- Hsieh had planned and made similar documentary material to govern a further performance in which other people, not the artist himself, would pass around a flaming torch for one year. But in a potential contradiction of his claims to not see art in the year from 1985 to 1986, he would observe the work in action. See “Hsieh, Tehching: proposal,” 1985–86, box 4, folder 57, subseries A: Artists Files, series III: Artists, Exhibitions, and Related Material, Fashion Moda Archive, Fales Library and Special Collection, New York University. ↵

- Charlotte Posenenske, “Offenbach, February 11, 1968,” Art International, no. 12 (May 1968): 50. ↵

- On Lozano’s dropping out, see Helen Molesworth, “Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano,” Art Journal 61, no. 4 (2002): 64–73; Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Lee Lozano: Drop Out Piece (London: Afterall, 2014); and Jo Applin’s revelatory monograph on the artist, Lee Lozano: Not Working (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018). Posenenske’s removal from the art world is covered well in an early contribution to the wider literature on this phenomenon: Alexander Koch, “Out of Practice, Out of the Picture: An Introduction to Leaving the Art World,” in “General Strike,” KOW 8 (2011): 2–5. She is profiled among many other artists who removed themselves from the art world or who have adopted an antagonistic position in relation to its operations in Martin Herbert, Tell Them I Said No (Berlin: Sternberg, 2016). ↵

- Applin, Lee Lozano, 19. ↵

- On these topics specifically, see Joan Kee, “Orders of the Law in the One Year Performances of Tehching Hsieh,” American Art 30, no. 1 (2016): 72–91; Faye Raquel Gleisser, “Rethinking Endurance: Pope.L, Tehching Hsieh, and Surviving Safety, 1978–1983,” in Risk Work: Making Art and Guerilla Tactics in Punitive America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023), 108–47; Jack Parlett, “New York Drifters: Tehching Hsieh and David Wojnarowicz,” Performance Research 23, no. 7 (2018): 54–62; and Joshua Chambers Letson, “Withdrawal,” in Tehching Hsieh: Doing Time, ed. Adrian Heathfield (Venice: Biennale de Venice, 2017), 36–44. ↵

- Tehching Hsieh, “I Just Go in Life: An Exchange with Tehching Hsieh,” in Adrain Heathfield, Out of Now: The Lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 336. ↵

- Chambers Letson, “Withdrawal,” 37. ↵

- Chambers Letson, “Withdrawal,” 37. ↵

- For a detailed account, see Julia Bryan Wilson, “Hard Hats and Art Strikes: Robert Morris in 1970,” Art Bulletin 89, no. 2 (June 2007): 333–59. For a wider view on cultural activism and the Vietnam War, see Francis Frascina, Art, Politics, Dissent: Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000); Matthew Israel, Kill For Peace: American Artists Against the Vietnam War (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013); and Melissa Ho, ed., Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019). ↵

- For a recent exploration of these activities, see Aaron Shkuda, “Artist Organizations, Political Advocacy, and the Creation of a Residential SoHo,” in The Lofts of Soho: Gentrification, Art and Industry in New York, 1950–1980 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 92–106. ↵

- Gallery and museum closures are often complemented by exhibitions, screenings, and shows focused on art and artists exploring the cultural politics of AIDS. See Michael Hunt Stolbach, “A Day Without Art,” Social Text, no. 24 (1990): 182–86. ↵

- Henry Flynt, “Concept Art,” in Anthology of Chance Operations, ed. LaMonte Young (New York: LaMonte Young and Jackson Mac Low, 1963), n.p. ↵

- Michael Oren, “Anti-Art as the End of Cultural History,” Performing Arts Journal 15, no. 2 (May 1993): 4. Another more recent account of Flynt singles out his interrelation with the New York musical vanguard in the pivotal year of 1964: Benjamin Piekut, “Demolish Serious Culture: Henry Flynt Meets the New York Avant-Garde,” in Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 65–101. ↵

- Flynt’s abandoning of art and culture for the worlds of politics and philosophy finds a corollary in the contemporaneous art collective Black Mask, which abandoned work in painting and expanded cinema to pursue pure political actions and demonstrations against financial and cultural institutions, morphing into a “street gang with analysis.” The new, provocative name of Black Mask is Up Against the Wall Motherfucker. Their history has been given a fantastic recent overview that touches on their relationship to Flynt in Nadja Millner-Larson, Up Against The Real: Black Mask from Art to Action (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023). ↵

- Quoted in Oren, “Anti-Art as the End of Cultural History,” 9. Originally: Henry Flynt, “My New Concept of General Acognitive Culture,” in dé-coll/age, no. 3 (1962), n.p., and three typescript pages numbered 35–37, a revised version of which is titled “Identification of Brend (1963; final transcript 1992). ↵

- Henry Flynt, “A Summary of My Results,” in Fluxshoe, exh. cat. (Cullompton: Beau Geste, 1972), 33–34; quoted in Oren, “Anti-Art as the End of Cultural History,” 9. ↵

- The paradigmatic example here is the dealer and curator Seth Seigelaub, who marketed and promoted conceptual art and the rights of artists to control and make money from their labor. See Alexander Alberro, Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004). Recent work by historian Christopher Howard has revived the near-forgotten conceptual art project of Terry Fugate-Wilcox to hoodwink the art world by promoting a gallery and set of group shows that never existed, offering a metacritique of the dematerialized nature of idea-driven art practice; The Jean Freeman Gallery Does Not Exist (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018). ↵

- For an overview of this boom, see Paul Ardenne and Michel Vale, “The Art Market in the 1980s,” in “The Political Economy of Art,” International Journal of Political Economy 25, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 100–128. ↵

- Hsieh, “I Just Go in Life,” 338. ↵

About the Author(s): Tom Day is Executive Director of the New American Cinema Group/ The Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

![Photocopied typewritten memo that reads "July 1, 1985 / Statment [sic] / I, Tehching Tsieh, plan to do a one year performance. I [redacted] do not do art, not talk art, not see art, not read art. / Not go to art gallery and art museum for one year. / I [redacted] just go on in life. / The performance [redacted] begin on July 1, 1985 and continue until / July 1, 1986. / Tehching Hsieh [signed and typewritten] / New York City](https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Fig.-1.jpg)