When We Gather

From cultural institutions to the virtual realm, to our homes, and to our beds, disabled artists are challenging the capitalist notion that our only option is to be independent and self-sufficient. The idea that we must take care of our needs alone leads to shame about our bodyminds and prevents us from gathering, organizing, building, and dreaming together in our communities. With the understanding of access as artistry, disabled artists expose the lie of American individualism and give us innovative ways to rethink how we gather.

In her book Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid, Shayda Kafai quotes crip-ancestor Stacey Milbern, who explains that “the work of supporting people rebirthing themselves as disabled or more disabled has a name. We are doulas.” Kafai expands, “Crip doulas stress that we do not grow into our present or our futures on our own; we move into these places with love and mentorship of our community. Together we rebirth ourselves into our disabilities or into our shifting bodyminds. We do this work with celebration and with struggle, we never journey alone.”1 After a major surgery triggered chronic illness in 2017, I experienced such a rebirth. Not knowing that the pain I was experiencing would not be temporary, I returned to graduate school and attended classes taught by artists Constantina Zavitsanos and Park McArthur, who shifted everything I knew about value, care, and togetherness. The reason I am able to identify as a disabled trans person, politically and with joy, is because of a lineage and legacy of queer-crip2 doulas and mentors like Zavitsanos and McArthur.

In 2019, Zavitsanos and McArthur, along with Arika, Amalle Dublon, Jerron Herman, Carolyn Lazard, and Alice Sheppard, organized the disability arts festival I wanna be with you everywhere at Performance Space New York and the Whitney Museum of American Art. I wanna be with you everywhere was described as “a gathering of, by, and for disabled artists and writers and anyone who wants to get with us for a series of crip meet-ups, performances, readings and other social spaces of surplus, abundance and joy.”3 This was my first large-scale disability community gathering, and it was also the first time I experienced a space that considered a wide range of access needs. This included stipends for local travel and a sensory room created with the needs of autistic people in mind but utilized by many. This was the first and only time I have experienced a sensory room in a cultural institution, and it’s a form of access that I often long for.

On the third night, Jerron Herman performed Relative in collaboration with Kevin Gotkin. Relative, “a dance party love letter to our community,” took us “to the accessible club of our underground dreams” (fig. 1).4 Herman speaks about the role of community in his practice during an interview with the Collegiate Association for Artists of Color. When asked, “What is the legacy you want to leave?,” he explains, “The legacy I want is to remain a person who has lived borderless, who has continued to examine the ways we create freedom, to create liberation, and liberating spaces. I don’t want to be known as necessarily a trailblazer but a communal worker. I think there are so many legacies to the right and left of me that I attach to, that my forward motion can seem independent but it’s not. . . . I do just want people to recognize that there’s a community here, to what I’m doing.”5 Herman’s embrace of interdependence was palpable during Relative, and his performance remains for me a warm and vivid memory of disability community love.

The dance began with several folks seated in chairs on the stage, with most of us seated in the audience. Before Herman entered, Gotkin began by playing music. Without any cue that the performance had started, everyone began chatting and moving around the stage. Herman, wearing a fantastic reflective silver jumpsuit, made his way through the already lively crowd, alternating between dancing in the center of the stage and dancing with others. Weaving the audience into the choreography, Herman made the boundary between stage and audience melt away. At this point, everyone had made their way on stage and was dancing together. Watching the footage of Relative later, I spot myself running into the arms of my partner, Francisco echo Eraso, who was already seated on stage. I stand behind him wrapping my arms around his shoulders as Gotkin’s soundscape slows, and we sway to the beat. My dear friend Kevin Quiles Bonilla comes over to us, arms high in the air with a skip in his step. We hug, and he puts his arms around our shoulders. He rubs my back, and we bring our heads close together and hold each other as more friends join us.

As Adelita Husni Bey writes in her review of I wanna be with you everywhere, “In a chronically inaccessible and isolating world, such togetherness is the forbearer of political agency.”6 When disabled people gather, we are doing so in a landscape, past and present, that actively works to remove disabled people from public life. From institutionalization, ugly laws, poverty-level SSDI (Social Security Disability Insurance) or SSI (Supplemental Security Income), and the inaccessibility of public transportation, the built environment, and beyond, society prevents disabled people from being together. Gathering under a Disability Justice framework,7 we create a crip-sociality where inclusion is non-negotiable; no one is a burden; and the work necessary to bring us together becomes a pleasure.8 As Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha prompts us in their book Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, “What does it mean to shift our ideas of access and care (whether it’s disability, childcare, economic access, or many more) from an individual chore, an unfortunate body, to a collective responsibility that’s maybe even deeply joyful?”9 Piepzna-Samarasinha’s call to see the joy of access is exemplified by the Remote Access party series.

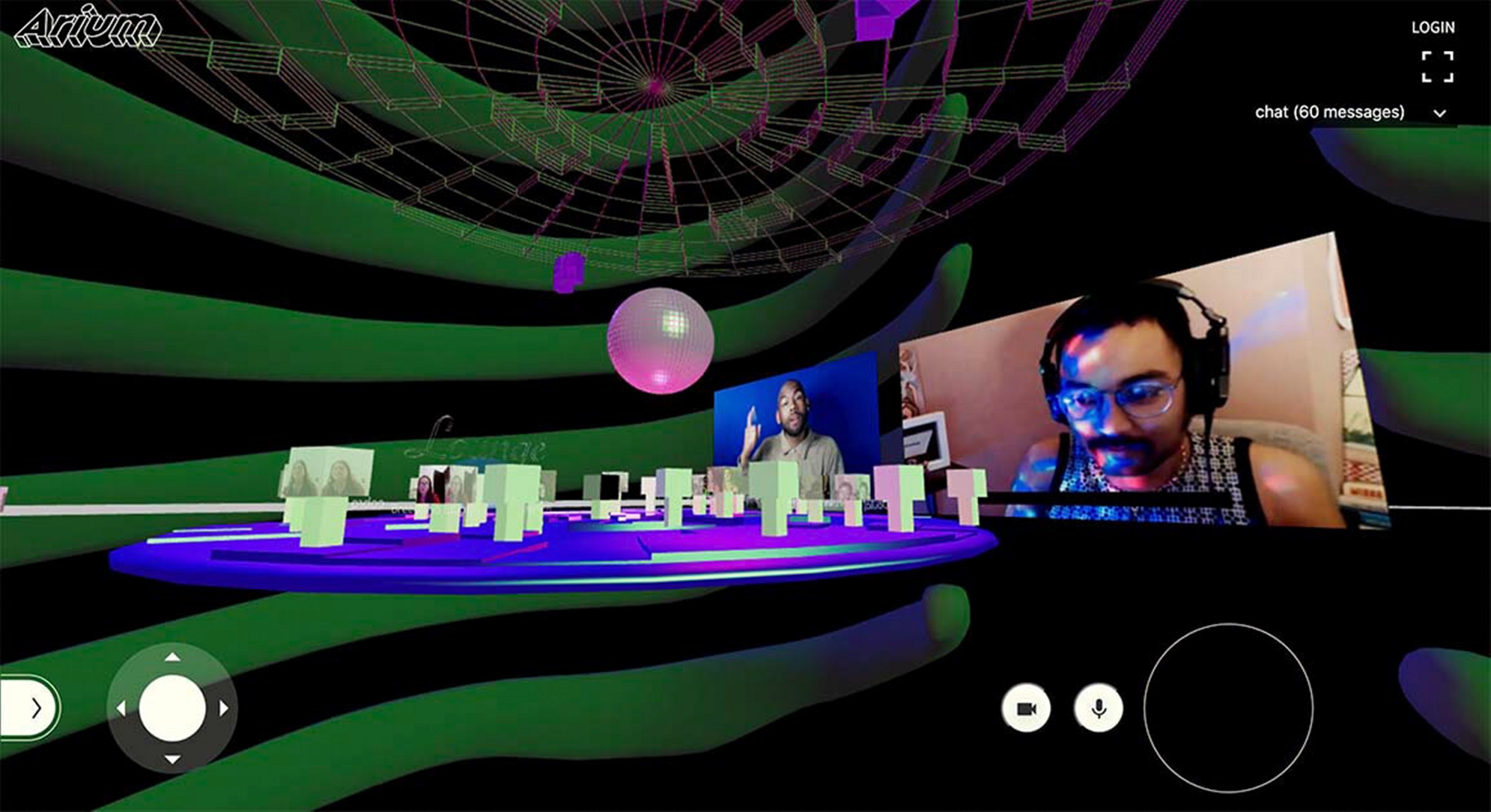

Remote Access is a series of crip nightlife events curated and designed by Critical Design Lab, “a multi-disciplinary and multi-institution arts and design collaborative rooted in disability culture” (fig. 2).10 A year and several iterations after Gotkin and Yo-Yo Lin hosted the inaugural Remote Access party, they took the party to a new dimension. Developed during Lin’s time in the CultureHub Residency Program, Remote Access: GlitchRealm was “a virtual dance party centering disability nightlife and access magic,” with the description, “Let’s blur the lines between URL/IRL and glitch endlessly, dancing in the lag together. Featuring a 3D virtual dance club and lounge, time-bending performances, live DJ sets, cyber rituals, real-time captions, audio description, ASL [American Sign Language], access doulas and more!”11 Through Arium, a 3D-meeting platform, partygoers could use their keyboards to move an avatar from the dance floor to the lounge and interact with other avatars. And as another option, you could Zoom in instead, which provided an experience similar to a typical Remote Access party.

The phrase “access magic” gives me the sense that anything is possible when our needs are valued. It is a stark contrast to having access needs constantly ignored or shut down and being told that the accommodations we need would be too hard, too complicated, not in the budget, not part of the aesthetic, or even an impossibility. Gotkin explains, “We just design a kind of ecology where the usual access features that we need regularly like ASL, CART [Communication Access Real-time Transcription] are there and then there are all these other responsive elements so that access needs are not this list of things but more like a set of discoveries and a process or coming into our bodymind, so I think access magic for me is when you break out of this ‘what accommodations can we provide for you at this event?’ It’s this whole other model.”12 Lin tells us, “I definitely feel like so much of what I’m witnessing with creating access is so cut and dry sometimes. And then little glimmers of access intimacy, you’re just like [sigh of relief] oh my god amazing, you just feel so held and so seen in that moment. For me the access magic is the magic of finally coming together and experiencing that together, that relational moment of ‘oh we can do this for each other and it feels great.’”13

The magic of coming together that Lin describes with joy is something that I felt from Shannon Finnegan’s Here to Lounge (fig. 3). This project is a site-specific “seating-centric space” originally made for Nook Gallery in Oakland, California. Recently, Here to Lounge traveled to Helmhaus in Zürich, Switzerland, as part of the exhibition All That You Touch, You Change. This most recent iteration included a selection of small works by artists Carly Mandel, Christine Sun Kim, Jeff Kasper, Jillian Crochet, Joselia Rebekah Hughes, Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, Pelenakeke Brown, Rebirth Garments, Sandra Wazaz, Yo-Yo Lin, Zach Ozma, and myself. The installation featured seating with cushions painted by Finnegan to invite rest with text such as “I’d rather be sitting. Sit if you agree.” The small works by the invited artists were placed on shelves, were attached to a window, rested on a table, and were laid on two Lazy Susans. Finnegan explains, “I was thinking about the idea of an exhibition where the artwork comes to the visitor, so as a pilot of that idea, I placed Lazy Susans in the space. I curated a selection of objects from other artists into the show—all things that can be picked up and touched. Sometimes we can’t gather in person but experience a type of togetherness through artwork, especially artist multiples and things that travel easily.”14

Finnegan also invited a range of expressions, giving the option to present a material, a book recommendation, a found object, or something more informal. One of the objects I sent to the recent iteration at Helmhaus was a stim toy made up of tiny magnetic balls that could be connected into shapes and squished like putty. Although I initially considered it an informal object, I treated it as an artwork, titling it The Neurodivergent Joy and Access Intimacy of Sharing Favorite Stims, indicating that what was being shown was not simply the object itself but rather the invitation to share a form of intimacy and stim with me through a touch experience across space and time.

As an autistic person, to share a stim or to stim with another goes against the mainstream pathological understanding of autism itself. Autistic people are still often thought to lack compassion, empathy, the need for affection, and the ability to bond with others. Yet I find this so ironic because in my experience autistic people and disability communities know so well the importance of cultivating safe spaces to gather and connect. This crip-wisdom is what allows me to understand autism as a skill set, a mode of access intimacy, and a framework for organizing and gathering.

Since the beginning of quarantine, I have been experiencing another rebirth as I grow into myself as an autistic person. As part of this process and reflection, I kept returning to the chapter in Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work titled “Crip Emotional Intelligence.” In this chapter they explain that disabled people have cultures and unique wisdom that able-bodied people could learn from.15 For me, one of the most impactful forms of “crip emotional intelligence” has been the way I have seen disability communities gather and operate from a framework of access as love.16 I wanna be with you everywhere and Herman’s Relative, Gotkin and Lin’s GlitchRealm, and Finnegan’s Here to Lounge are projects imbued with crip love through their insistence on togetherness. As journalist s.e. smith writes in “The Beauty of Spaces Created for and by Disabled People,” “The first social setting where you come to the giddy understanding that this is a place for disabled people is a momentous one, and one worth lingering over. . . . The experiences blend together, creating a sense of crip space, a communal belonging, a deep rightness that comes from not having to explain or justify your existence. They are resting points, even as they can be energizing and exhilarating.”17 Reflecting on my own experiences of crip space, I find these “resting points” in the ways disability communities gather and create spaces that hold us and nourish us. Together we dream worlds that embrace our wholeness.18

Cite this article: Alex Dolores Salerno, “When We Gather,” in “Exploring Indisposability: The Entanglements of Crip Art,” Colloquium, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13056.

Notes

- Shayda Kafai, Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021), 170. ↵

- “Crip”, a shortened spelling of the slur “cripple,” is often used as a term of empowerment. Some people of color spell it “Krip.” I use “queer-crip” to point to an intersection of my identity and community. ↵

- I wanna be with you everywhere, Performance Space New York, October 1, 2019, https://performancespacenewyork.org/shows/i-wanna-be-with-you-everywhere. ↵

- I wanna be with you everywhere. ↵

- “BORDERLESS ART | An Interview with Jerron Herman,” Collegiate Association for Artists of Color, December 14, 2020, video, 23:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FiVSte9Ar2k. ↵

- Adelita Husni Bey, “Adelita Husni Bey on I wanna be with you everywhere at Performance Space New York,” Artforum, May 29, 2019, https://www.artforum.com/performance/adelita-husni-bey-on-i-wanna-be-with-you-everywhere-79790. ↵

- Disability Justice moves beyond the single-issue rights-based framework of disability rights and foregrounds the intersectionality of disability issues and disabled people. ↵

- “Crip-sociality” is a term I first heard used by Francisco echo Eraso. ↵

- Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018), 33. ↵

- “Meet the Lab,” Critical Design Lab, accessed March 12, 2022, https://www.mapping-access.com/lab. ↵

- “Remote Access: Glitchrealm,” CULTUREHUB, accessed March 12, 2022, https://www.culturehub.org/remote-access-glitchrealm. ↵

- “Remote Access: Glitchrealm,” CULTUREHUB, accessed March 12, 2022, https://www.culturehub.org/remote-access-glitchrealm. ↵

- Yo-Yo Lin, Zoom conversation with author, February 16, 2022. Mia Mingus describes this sensation as “access intimacy”; see Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link,” Leaving Evidence, May 5, 2011, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link. ↵

- “Here to Lounge,” Shannon Finnegan, accessed March 12, 2022, https://shannonfinnegan.com/here-to-lounge. ↵

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, “Crip Emotional Intelligence,” in Care Work, 69–73. ↵

- “Access Is Love,” Disability Intersectionality Summit, accessed March 12, 2022, https://www.disabilityintersectionalitysummit.com/access-is-love. ↵

- s.e. smith, “The Beauty of Spaces Created for and by Disabled People,” in Disability Visibility: Twenty-First Century Disabled Voices, ed. Alice Wong (New York: Vintage, 2020), 272. ↵

- Here I reference Principle #5: Recognizing Wholeness, from “10 Principles of Disability Justice,” Sins Invalid: An Unshamed Claim to Beauty in the Face of Invisibility, September 7, 2015, https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice. ↵

About the Author(s): Alex Dolores Salerno is an interdisciplinary artist in Brooklyn, New York.