Fanny Palmer: The Life and Works of a Currier & Ives Artist

Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein

Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, New York State and Regional Studies Series, 2018; 408 pp.; 26 color plates; 268 illus. (color and b/w illus); (ISBN: 9780815610953); Hardcover: $60.00

Charlotte S. Rubinstein’s Fanny Palmer: The Life and Works of a Currier & Ives Artist, published posthumously (Rubinstein passed away in 2013) and edited by Diann Benti, is an important contribution to the history of American art and visual culture. It is the first monograph about Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812–1876), “an enterprising professional [artist], one of the most versatile and prolific lithographers of her day” (xiv). Fanny Palmer serves as both a biography of this British graphic artist, who initially worked in England but spent most of her career in the United States, and a catalogue of Palmer’s known works. It not only reflects the work of its author, but also that of the editor, Benti, and the American Historical Print Collectors Society, a community of scholars and collectors who recognize Palmer’s significance and supported the publication of Rubinstein’s unfinished manuscript. The monograph will be a reference for any scholar interested in Palmer’s work and her role in nineteenth-century American visual culture. It includes twelve chapters and a checklist of the artist’s works, covering the full length of her career, from prints and drawings created in Leicester, England, to those made during her American years. The volume is lavishly illustrated with almost all of Palmer’s identified works reproduced, either as small vignettes in the checklist or as large color and black-and-white illustrations distributed throughout the text. In addition, a series of full-page plates of her most important lithographs appear in the “Gallery of Prints by Fanny Palmer” section, located in the middle of the book.

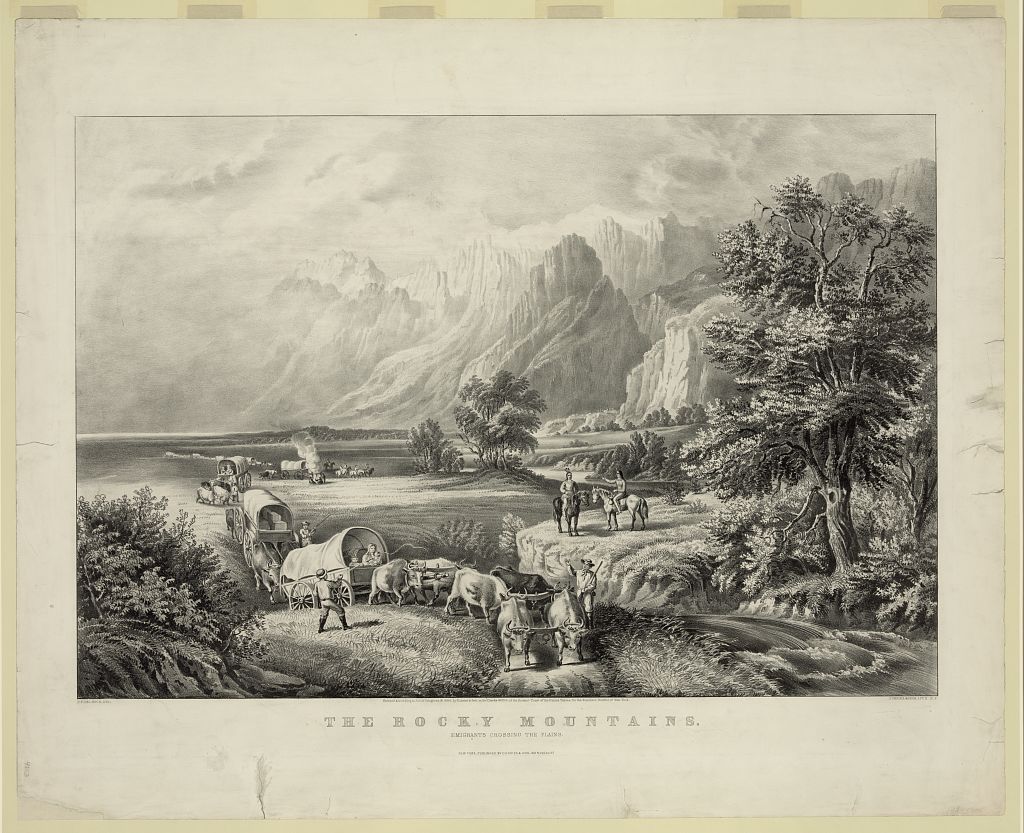

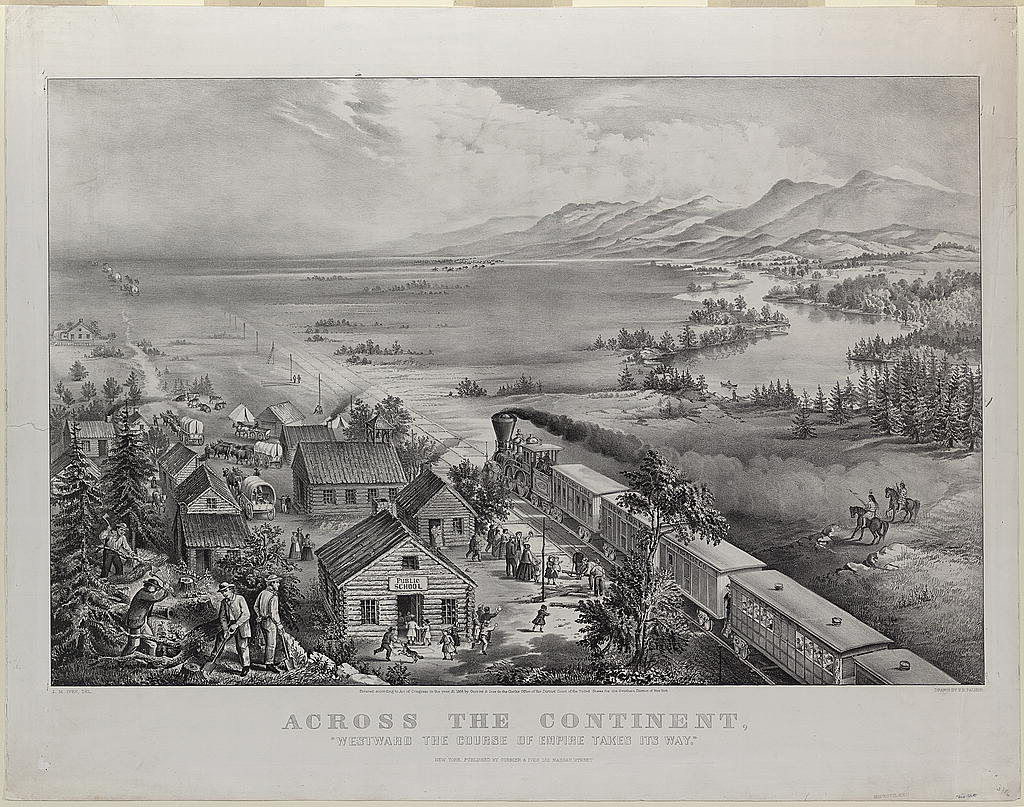

Among historians of American art, Palmer is primarily known for her canonical views of Western expansion, such as The Rocky Mountains. Emigrants Crossing the Plains (1866; fig. 1), and Across the Continent. “Westward the Course of Empire Takes it Way” (1868; fig. 2), both published by the New York lithography firm Currier & Ives. Rubinstein’s book reveals the stature of this Victorian artist and invites the reader to reconsider her significance in the history of American printmaking by looking beyond her years with the self-proclaimed publisher of “Cheap and Popular Prints.”1 Palmer created more than 150 compositions for Currier & Ives, many of which are now among their iconic images. She also established two lithographic firms with her lithographic printer husband, one in Leicester, England, and one in New York (F. & S. Palmer).2 Within five years of their arrival in New York, and before Fanny’s time with Currier & Ives, the Palmers had produced more than two hundred prints. Fanny’s work included landscapes and city views, botanical illustrations, architectural drawings, advertisements, cartoons, war illustrations, sheet music, portraits, sporting pictures, images of ships and churches, and more. She exhibited and competed for awards at various exhibitions. And she taught young male apprentices in her Brooklyn studio— including Joseph Knapp, future partner of the lithography studio Sarony, Major & Knapp —who became innovators or founders of major lithographic publishing firms.3 As Rubenstein demonstrates throughout the book, Fanny Palmer exerted impact on almost every aspect of her field. This text therefore presents an opportunity to reassess Palmer’s importance and consider why she has been sidelined in art-historical scholarship.

The first eight chapters of the book cover the artist’s life and career, with chapters one and two focusing on her childhood in an upper-middle-class family in Leicester and her early career as a lithographer. Rubinstein locates the origins of Palmer’s artistic ambitions in her education at Mary Lynwood’s Academy in Leicester—emphasizing a lineage of professional women artists going back to the eighteenth century.4 She shows that Palmer was professionally trained in lithography in the London workshop of Day & Haghe, considered to be the best English lithographic firm at the time. Rubinstein also uncovers information about Palmer’s husband (Edmund Seymour Palmer, whom she married in 1832) and the couple’s early collaborations, as they established a lithography firm in Leicester in the early 1840s.

Chapters three and four describe the Palmers’ early years in New York and how they reestablished their printing business in the American metropolis. The strength of these chapters lie in their demonstration of the Palmers’ impressive output during this period and their references to innumerable archival sources, both of which provide insight into Fanny and Seymour’s business model prior to his retirement from printing to become a tavern keeper. Taken together, the prints and archival sources suggest that the couple and their firm quickly connected with major players of the city’s publishing and artistic circles. Although the Palmers’ firm ultimately failed, what the reader learns about its output and production practices contributes to a better understanding of the mid-nineteenth-century lithographic trade in New York. However, as a result of the author’s preferred focus on the iconography and technical proficiency of the prints, the Palmers’ early relationships with large publishers who tend to dominate our understanding of nineteenth-century American print and visual culture, such as Nathaniel Currier and Louis Prang, is not sufficiently fleshed out. The section ends with Fanny’s first commissions for Nathaniel Currier in 1849, a series of sporting prints featuring her husband and his hounds in various settings. This conclusion introduces the reader to the business relationship between Palmer and Currier, one that would shape her career for the next twenty years and determine the reception of her work in the twentieth century.

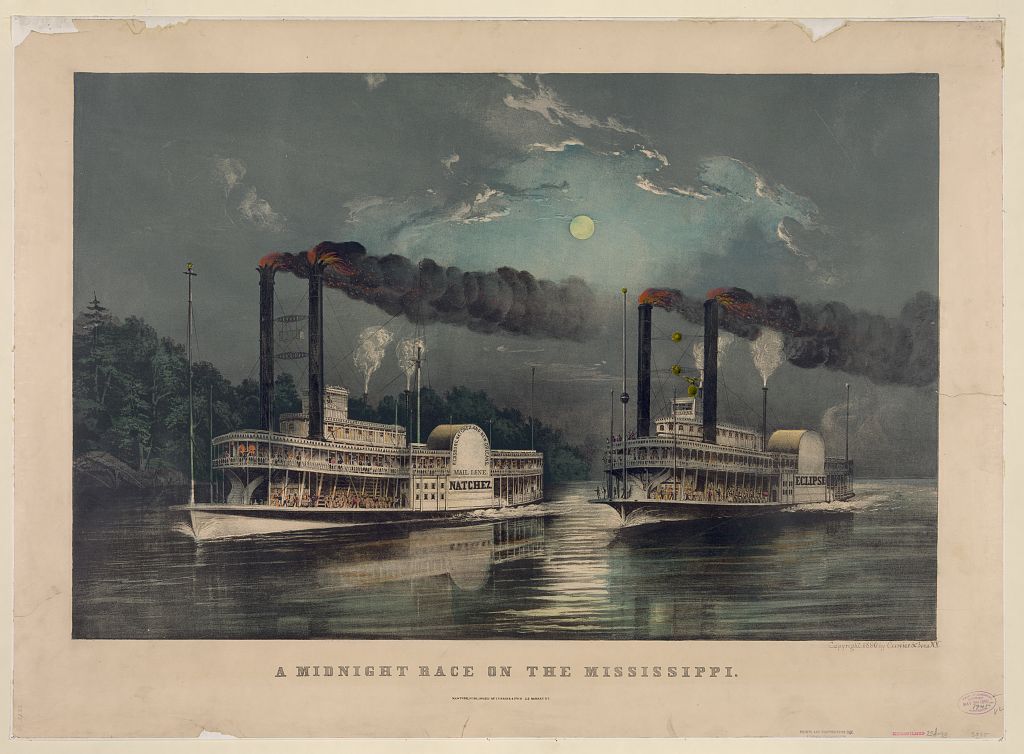

The next four chapters are dedicated to Palmer’s Currier & Ives period. Building chiefly on two fundamental sources—the unpublished research papers of Harriet Endicott Waite (Archives of American Art) and Harry Peters’s monograph Currier & Ives—Rubinstein describes the operations of Currier & Ives and gives the reader context for understanding Palmer’s role within the firm in chapter five.5 She also evokes the life of several key figures associated with the firm, including Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888) and James Ives (1824–1895), Louis Maurer (1832–1932), Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819–1905), and George Henry Durrie (1820–1863). Chapters six and seven focus on Palmer’s Currier & Ives prints and situates them in relation to artistic trends and visual culture of the period. Rubinstein follows Bryan Le Beau’s approach, showing that Palmer’s Currier & Ives lithographs tended to present an unrealistic view of America that embodied Northern, Protestant, and white middle-class values and prejudices.6 Readers familiar with Le Beau will recognize well-known prints, such as A Midnight Race on the Mississippi (fig. 3), American Express Train, and Mississippi in Time of Peace, with its companion picture Mississippi in Time of War, and discover less familiar still lifes, landscapes, and Civil War images, which used innovative compositional and lithographic techniques.

The book ends with a couple of very short chapters that examine the reception of Palmer’s prints after her death in 1876 and describe how they attracted attention in the twentieth century. These chapters interrogate the significance of Palmer’s contributions to the history of American art, address her lithographic technique, and consider the ideological content of the prints. This, however, is the most uneven section of the book, which was largely left unfinished in 2013.

Calling her “the Norman Rockwell of her time,” Rubinstein positions Palmer as a ubiquitous nineteenth-century American artist whose legacy resides in the drawings, watercolors, and lithographs she left behind. Beyond the visual and technical perfection of her lithographic work, Fanny had a keen ability to give visual form to Currier & Ives’s romanticized views of American life. In comparison with her earlier work in particular, Palmer’s images of happy suburban and country life created for Currier & Ives, such as American Farm Scenes, seem not entirely her own; they instead promote the values and experiences of the firm’s partners and intended audience. Because of this, Palmer’s images present a scholarly conundrum, one that is not entirely resolved by Rubinstein’s text. Despite her experiences as an independent artist and the main breadwinner for her family, Palmer’s Currier & Ives compositions consistently avoid the social, racial, and gendered conflicts of her own time. Her prints often appear inconsistent with Rubinstein’s depiction of Palmer as an independent woman artist. In addition, Rubinstein describes Palmer as working alongside men in the Currier & Ives factory, the heart of the firm’s activities. In fact, she worked from her home in Brooklyn, where she taught and employed young male artists. In the current limited archival records, we do not know the exact nature of her contract(s) with Currier & Ives. Nevertheless, we do know that Palmer designed and drew her compositions in her home in Brooklyn, not in the firm’s studio in Manhattan. Positioning her studio independently at home was a sound business decision, as independent work was far more lucrative than employment as a staff lithographer in the Currier & Ives factory. This decision allowed Palmer to employ paying apprentices and hire young lithographers when needed.7 Last but not least, it allowed her to maintain the social status of a middle-class, widowed woman (Edmund Palmer died in 1859). To what extent she chose her topics is up for debate. Did her work with Currier & Ives limit her possibility of expression to prescribed subjects and formats, or were her subjects her own choice? These questions go unanswered.

Diann Benti’s thoughtful editorial work has respected the incomplete nature of Rubinstein’s manuscript, opening many areas for further research. The author’s research had included lithographic descriptions in the manuscript checklist, which were removed because they were unfinished. However, incomplete passages on the artist’s lithographic technique were left in the text, instead of becoming a topic for in-depth inquiry. Indeed, what did Palmer and her husband absorb in the London workshop of Day and Haghe? To what extent did the couple impact lithographic practice in New York with the sophisticated use of tint stones, colored inks, and papers found in F. & S. Palmer’s early American publications, such as Church of the Holy Trinity. Brooklyn Heights (fig. 4)?8 How did Fanny and Seymour’s collaboration compare with the business practices of other small printers and publishers in London and New York? The complete list of Palmer’s works serves as a starting point for working through such questions and for further research into her techniques and English lithographic trade practices, both of which promise to be critical for future scholarship.

Fanny Palmer’s work and the history of her workshop and printing firm have much to tell us about how innovations in printing and lithography spread and flourished in mid-nineteenth-century New York. Despite its incompleteness, Rubinstein’s research and monograph present a much-needed opportunity to ask important questions and better appreciate this remarkably talented and prolific artist and her role in New York’s lithographic trade. Fanny Palmer also demonstrates that research into her businesses and their relation to the city networks of small studios, institutions, and large publishers will be necessary to develop a more refined understanding of this critical moment in the history of American visual culture.

Cite this article: Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, review of Fanny Palmer: The Life and Works of a Currier & Ives Artist, by Harlot Streifer Rubinstein, ed. Diann Benti, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2056.

PDF: Delamaire, review of Fanny Palmer

Notes

- An early broadside for Nathaniel Currier advertised “Colored engravings for the People,” although he only published lithographs (c. 1838–57, private collection). Later, “Publishers of Cheap and Popular Pictures” appeared on the firm stationery (Reproduction of Currier & Ives recipe for making lithographic writing ink, Harriet Endicott Waite research material concerning Currier & Ives, 1923–56, Archives of American Art). ↵

- Fanny and her husband, Edmund Seymour Palmer, used various abbreviations. Their collaboration in Leicester is most often marked “F. F. Palmer, litho. E. S. Palmer, Printer.” In New York, their prints are marked “F. Palmer, lith. Lith. of E. Palmer,” “F. F. Palmer. Lith. of E. S. Palmer,” and various forms of “F. & S. Palmer Lith.” Since the couple used the latter form most frequently, I refer to the firm as “F. & S. Palmer.” ↵

- Palmer, her husband, and her sister exhibited at the American Institute fairs in 1846, 1847, and 1948. See Ethan Robey, “The Utility of Art: Mechanics’ Institute Fairs in New York City, 1828–1876” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2000), 573. ↵

- Linwood/Lynnwood was an internationally known artist of needlework compositions. She specialized in the full-scale translation of old master paintings into needlework, using irregular stitches to evoke brushstrokes. In the late eighteenth century, her work was in high demand among the royal courts of Europe, and she had a permanent exhibition on Leicester Square in London. ↵

- Harriet Endicott Waite research material concerning Currier & Ives, 1923–56, Archives of American Art; and Harry T. Peters, Currier & Ives, Printmakers to the American People (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, 1929–31). ↵

- Bryan F. Le Beau, Currier and Ives: America Imagined (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001). ↵

- Stephanie Delamaire and Joan Irving, “Was Fanny Palmer the Power House behind Currier & Ives?” Art in Print 8, no. 2 (July/August 2018): 25–31. ↵

- Preliminary research on Palmer’s papers and inks conducted at Winterthur’s conservation and analytical laboratories will be published in Stephanie Delamaire and Joan Irving, “Fine or Commercial Lithography: A Reappraisal of Fanny Palmer’s Prints” in Laid Down on Paper: Printmaking in America during the Life of Fitz Henry Lane, ed. Caroline Sloat (Gloucester, MA: Cape Ann Museum, forthcoming 2019). ↵

About the Author(s): Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire is Associate Curator of Fine Arts at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library