Fata Morgana: Jean-André Castaigne, the American Indian, and American Artistic Aspirations in France

When I was working on my dissertation on constructions of American cultural identities in fin-de-siècle Paris at Washington University in St. Louis in about 2009, I stumbled upon a five hundred page English-language novel published in 1904 by a French artist. Entitled Fata Morgana: A Romance of Art Student Life in Paris, its protagonist is an American art student, aptly named “Phil Longwill.” The novel was written and illustrated by Jean-André Castaigne (1861–1929), a painter who today is little known. Its title page announced its dedication “to his many American friends.” I had never seen it cited before in the scholarship on American artists in France, though its full text was available on Googlebooks.1 Intrigued, but uncertain if the novel would be worth the time it would take to read, I haphazardly used an entire month’s worth of free printing at the St. Louis Public Library to print a double-sided copy and had it spiral bound to cart around with me. Reading passages while on the Metrolink or at the gym, I made my way slowly through the book. In the end, this wandering, uncertain read paid off. An anecdote or image from the novel appears in every chapter of the dissertation.2 What makes this book special, aside from the fact that it had been relatively unstudied, is that it falls directly in the fault lines between the French and American art worlds during the fin de siècle.

The author’s transatlantic experiences primed him for insightful commentary about the prevalent American art practice of study in Paris. The French painter was familiar with the American artist community in Paris by teaching at the Académie Colarossi in the 1890s, and he participated in an American Art Association of Paris exhibition in 1898.3 After his own academic training in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) and Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889), Castaigne taught painting in Baltimore in the 1890s.4 He forged a career in the American art world by submitting paintings to the National Academy of Design and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.5 He also produced illustrations for American journal articles and books.6 These interactions inspired Castaigne to write his novel, which is both a celebratory and a mocking account of American art practice in France at the fin de siècle with its simultaneously endearing and troubling protagonist. The complexities of identity developed in the book, alongside its caricatural illustrations that polarized stereotypes of French and American characters, offered a key point of access to the questions I was asking in my dissertation, such as, how were American art and culture perceived in France in a period in which thousands of American artists were working in the foreign capital?

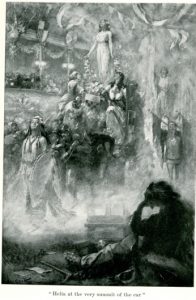

A second related discovery happened two years later, in 2011, while I was living in Paris to continue research for my dissertation. I spent a week in the charming seaside village of La Rochelle to explore the collections of the Musée de Nouveau Monde, an institution that highlights French interest in and travel to the New World, broadly defined as North, Central, and South America, from what was once an important seaport for travel to the east.7 In the collections storage vault among Wild West board games and dinner plates decorated with episodes from Chateaubriand’s Atala, 1801, I stumbled upon a grisaille painting hanging on the rack by the entrance to the room, which had been labeled inconclusively, and for lack of a clearer iconographic definition, as a “Columbus Day parade” (fig. 1). With its unclear title, the painting was not even on my list of objects to view. But I recognized the image immediately, not as a parade for an American holiday that was unofficial until 1937, but as the source for the frontispiece of Castaigne’s 1904 novel (fig. 2), and I froze in my tracks in the dimly lit room. As a piece of material culture related to mass reproduction, Castaigne’s painting is a remnant of that process with its range of white, black, and gray, a singular object with texture and impasto that is rendered invisible and flattened in the reproduced image. Yet even if the painted surface evaporates in the illustration, in the circulation of the image, a multi-layered commentary can be traced about how the the important and controversial act of “playing Indian” in the Paris artists’ community.

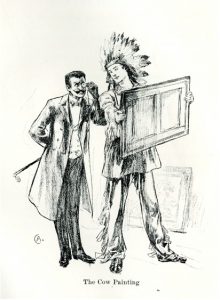

In the novel, Castaigne’s illustrations depict Phil “playing Indian” three times, and these images reveal the conflicted perceptions of American culture in the foreign capital. In addition to the frontispiece, where Phil appears twice and to which I will return, at the beginning of the novel, the reader is introduced to the character as he returns from the Bal des Quat’z’Arts in the morning, puttering around his studio in the feathered war bonnet and leather skin clothing of his costume (fig. 3). Significantly, Castaigne establishes his main character by pandering to international expectations of Americanness by means of the figure of the American Indian. As critic Anna Bowman Dodd (1858–1929) reported in 1907, “All the [Latin] ‘Quarter’ believed the Red Indian to be the only true American.”8 Castaigne describes the peculiarities of the artist:

Certainly, Phil was an odd figure in his Indian dress. If he lowered his head he risked scratching his chin against the bear’s claws of his collar. He was clad in leather and glass beads. There were feathers down his legs and a calumet was stuck in his belt.9

Castaigne pointed out the foreignness and discomfort of Phil’s costume, but also used it to consider the complexities of character between his “savage” exterior and his bourgeois status, gleaned from French ancestry. Castaigne described, “He had the look of a veritable savage. No one would have recognized in him the society painter, descendant of Philidor de Longueville, the Protestant banished from France by Louis XIV, who became a great proprietor in Virginia.”10 Through the American Indian costume, Castaigne implied a tension between the savage and noble aspects of Phil’s character; despite a “savage” façade, he was a bourgeois painter with greater interiority than his costume would suggest.

This scene serves as a mocking metaphor of Phil’s national and artistic identities. Before the “veritable savage” had the chance to change his costume from the night before, the French critic Caracal and Phil’s bête noire, arrived to inspect his latest paintings (fig. 3).11 When he entered, “Caracal turned the glitter of his monocle on the Indian costume. ‘Very, very curious—very amusing—very American! From last night’s ball, doubtless?’ For once there was nothing to say, and Caracal was right. It was really very American.” Caracal employed parallel language with his succeeding comment: “your talent is very interesting, very American.”12 Caracal aligned Phil’s costume with his painting approach, defining both as explicitly “American,” and by association, as “savage.” Phil’s costume is even more pronounced as opposed to Caracal’s clothing. While Phil’s loose fitting clothing is fringed, the French critic wears a sleek suit and holds a maulstick behind his back. His bowtie enhances the twist of his moustache, and he leans slightly forward with his monocle in hand and with perfect control.

The paintings in his studio exemplified the link between savagery and Indian dress mediated by Phil’s costume. In advance of this studio visit, Castaigne explained that Phil had turned his own academically-trained paintings to face the walls. In their place, he displayed a carefully constructed and falsely autographed collection of the worst paintings he could find to trick the nosy critic. In an anecdote that gives the illustration its title, this array included a painting of cows that was “so fearful that Phil, the first time he saw it, scarcely knew whether to groan, or shout with laughter.”13 Castaigne described that these included “all the grotesque works which he had found among the art-junk-dealers in his chance explorations. If he found a picture cast aside,—provided it was utterly bad,—he bought it.”14 Some of the paintings were gathered from “the slums of impressionism and modern style” and Phil added his signature to each.15 Castaigne implied that these quickly dashed off paintings appear unfinished and non-naturalistic with exaggerated color and shapes. In the cow painting, for instance, “the frightful beasts lowered their crocodile heads to graze in a fantastic meadow whose daisies resembled white plates with egg yolks in the middle.”16 His “savage” dress and the paintings were purposefully paired, as Phil “with his glass beads jingling at every step, took the cow painting and set it in full light.”17 As juxtaposed with Caracal’s costume, Phil’s character in person and in art were constructed as lacking poise and control. In linking Phil’s costume with these paintings, Castaigne implied the performed nature of the American artist as American Indian. He suggests that the American Indian is more in touch with nature and authentic experience because Phil told Caracal that these are the paintings “which I paint for myself alone, those into which I put my soul.”18 But this notion is negated as a ruse that mocked a belief in authenticity associated with indigenous America. The author demeans Phil’s role as a serious artist by presenting his duplicity. The use of the American Indian costume in Fata Morgana thus criticizes American artists’ adoptions of naive artistic positions as mere postures to gain advancement in the French art world.

Caracal mockingly linked the “primitive” style in the paintings with Phil’s American identity in the frame of the American Indian. This move suggests anxieties about the relationship between American artists and the French art establishment. By way of revenge at Phil’s trick, Caracal commented sneakily, “Very—very interesting—very original. That’s art—that ought to be at the Luxembourg! Oughtn’t it, cher ami?”19 Caracal’s repetition of phrasing reminded the reader of his claim that Phil’s costume was “very interesting—very American.” The critic offered to buy the cow painting, and Phil simply gave it to him.20 In an attempt to ruin Phil’s reputation, Caracal presented the painting to the Luxembourg Museum, and used his connections to convince the jury to accept it. Phil read this act as a deliberate attempt to “discredit American art by presenting to the public a wretched work bought for a few sous in a junk-shop.”21 Castaigne joked about the minimal required level for American paintings to be accepted by the Luxembourg Museum and revealed his protagonist’s concerns about the reception of American art in Paris. In the mutual deception within this narrative, Castaigne, an artist trained in the French academy, provides a biting comment about the advanced art of Paris. Castaigne positions himself against the kind of artlessness invited by the discourse around “playing Indian.” Furthermore, he mocks the complicity of the French establishment in allowing for the presentation of unworthy paintings as serious works of art.

In dialogue with contemporary conversations about the role of the French government in purchasing American art, this plot twist implied Castaigne’s intersection with French anxieties about the prevalent and well-publicized presence of American artists in France. In the late nineteenth century, the French government acquired more paintings by American artists than by any other international community working in Paris.22 Castaigne’s mocking of Phil paralleled French fears that American artists had adopted French artistic styles too successfully and would cut into their market.23 In addition to mocking American projections of the American Indian in France, Castaigne participates in a frequent French practice of casting jokes about American artists as American Indians to belittle their work as they increasingly competed for French and American art markets. American artists working in Paris indeed often noted that their French colleagues would employ stereotypes about Native Americans to mock them. For example, according to the American academic painter Kenyon Cox (1856–1919), who studied in Paris in the late 1870s and early 1880s, when the nationality of American artists was recognized upon their entry to the ateliers at the École des Beaux Arts, French impressions of Native American war whoops resounded throughout the room.24 The stereotype of non-Native American artist as Native American was thus constructed both by American artists working in Paris, and by the French artists who interacted with them, albeit with different goals. American artists associated themselves with Native America to claim to be culturally distinct, whereas French artists used these tropes to belittle and de-professionalize American art practice in France. Phil’s hope of becoming an accepted artist in French society was mediated through his presentation as an American Indian. Upon returning from the Bal de Quat’z’Arts, Phil “in his half sleep” dreamed of Helia, a childhood friend and his model, as Fata Morgana on a parade float designed for the party.25 Castaigne described that Phil, “dozing in his arm-chair, saw himself, clad in his magnificent Indian costume, marching at the head of the car, brandishing his tomahawk in honor of Morgana.”26 In the frontispiece for the novel (fig. 2), Castaigne depicted Helia on the top of a carriage, with the caravan of figures led by a figure dressed in full Native American regalia. Phil appears twice in this image—in real time as the American Indian lying across the foreground, dreamily gazing off into distance with the feathers from his war bonnet cascading down his back—and within his own vision which appears as a mirage almost sitting on his empty artist’s easel, leading the group in the parade with his head held high. The sounds of the procession are almost palpable, with the balconies jammed with people watching the parade and waving flags.

But Castaigne includes visual cues to undercut Phil’s goals. As the artist imagined his acceptance into French artistic society through marching at the head of a parade, the dreamlike quality of the scene implied that these goals would not be attained. This impression was reinforced by the title of the book itself, Fata Morgana, an unreachable vision, allegorized by the parade float. In the context of the novel, the primitivism of Phil’s costume undercuts the artist’s goals to become a famous Salon painter, until he can costume and comport himself in the same manner as Caracal. Success in the French academic system remains an elusive dream for Phil. Castaigne’s caricature emphasized the incompatibility of Phil’s simultaneous roles—society painter and Native American.

Castaigne’s depiction participates in a larger cultural practice of treating the American Indian as a metonym for non-Native American culture in France. In a period during which American artists were told by critics like Henry Tuckerman (1813–1871) that American Indian iconography could offer a unique contribution to the art world, Castaigne’s choice is unsurprising. “Tales of frontier and Indian life… awaken instant attention in Europe,” wrote Tuckerman in 1867. “If our artists or authors,” he persevered, “wish to earn trophies abroad, let them seize upon themes essentially American.”27 By the late nineteenth century, American artists in Paris had taken up that challenge, submitting many objects depicting western subjects to the Paris Salons and Universal Expositions.28 There is a likely dialogue between Castaigne’s illustration and the American imagery that allegorized the American Indian as an idealized icon for American art, such as Czech artist Luděk Marold’s (1865-1898) illustration “Art Presented to America” (fig. 4). This image topped the heading of a chapter on the art of the United States in an 1893 book, Art and Architecture: World’s Columbian Exposition by William Walton, a volume for which Castaigne also submitted illustrations. Marold’s illustration opposes an American Indian wearing a feathered war bonnet and buckskin clothing sitting on a throne at the left and the artistic muses who stand on sketches at the right. A large eagle bursts through the picture frame at the left of the scene, its wing tips extending beyond the edge of the image. In its placement at the start of an essay on the progress of art in the United States, the image literalizes Tuckerman’s dictum; the nude female figure at right raises her palette high in the air and regards the stoic American Indian and dynamic eagle with intrigue as a new artistic subject. Castaigne’s depiction of Phil’s haughty face in the parade echoes this figure (fig. 1), but instead of using the American Indian as a subject in art, Castaigne takes his character further to actually perform as an American Indian. It marks a distortion of Tuckerman’s and Marold’s suggestions; here, the icon of the American Indian becomes exaggerated to the persona of “playing Indian.”

Castaigne’s painting and the illustration made from it are truly transnational objects. In a French public collection, but reproduced and printed in an English-language volume and published in New York, its iconography imagines Franco-American cultural and artistic exchange within the impossible dream of an American art student in Paris. Castaigne’s mocking portrayal of his non-Native American artist as an American Indian and debasing of his protagonist reveals a fictional version of what was a common practice of white American artists “playing Indian” in Paris. These performances paralleled frequent jokes and insults from French artists and critics in the ateliers who linked non-Native American artists with Native Americans to belittle their work as they increasingly competed for French and American art markets. This analysis is part of a chapter in my book project on the American West in France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, entitled “Transnational Frontiers: The Visual Culture of the American West in the French Imagination, 1867–1914,” that considers the vicissitudes of “playing Indian” in late nineteenth-century France, and how different images of this act resonated within specific French and Franco-American contexts.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1548

PDF: Burns – Fata Morgana

Notes

Thanks to Valerie Ann Leeds and Kevin Murphy for their suggested edits to this text.

- On American art study in Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century, see H. Barbara Weinberg, The Lure of Paris: Nineteenth-Century American Painters and Their French Teachers (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1991); Lois Marie Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1990); and Kathleen Adler and Erica Hirshler, et al., Americans in Paris, 1860–1900, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery, 2006). ↵

- Emily C. Burns, “Innocence Abroad: The Construction and Marketing of an American Artistic Identity in Paris, 1880–1910,”( PhD diss., Washington University in St. Louis, 2012). ↵

- “The Second Exhibition,” Quartier Latin 4, no. 19 (February 1898): 673–74. On this artists’ club, see Emily C. Burns, “Revising Bohemia: The American Artist Colony in Paris, 1890–1914,” in Foreign Artists and Communities in Modern Paris, 1870–1914: Strangers in Paradise, eds. Karen Carter and Susan Waller (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2015), 186–209; and Emily C. Burns, “‘Of a Kind Hitherto Unknown’: The American Art Association of Paris in 1908,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 1 (Spring 2015): http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/spring15/burns-on-the-american-art-association-of-paris-in-1908. ↵

- On Castaigne, see “Art Notes,” American Register, November 11, 1893, 6; John Shirley Fox, An Art Student’s Reminiscences of Paris in the Eighties (London: Mills and Boon, 1909), 107–10; L.R.M. “André Castaigne,” Critic 20 (July 22, 1893): 57; Forrest Fenn, The Beat of the Drum and the Whoop of the Dance: A Study in the Life and Work of Joseph Henry Sharp (Santa Fe, NM: Fenn Pubishing, 1983), 92; and Michael McCue, Paris and Tryon: George C. Aid (1872–1938) and His Artistic Circles in France and North Carolina (Columbus, NC: Condar Press, 2003), 31–32. See also Emily Burns, “Puritan Parisians: American Art Students in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris,” in A Seamless Web: Transatlantic Art in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Cherryl May and Marian Wardle (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Press Scholars, 2014), 124–26; and Burns, “Revising Bohemia,” 99. ↵

- Marcia Naylor, The National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1861–1900, vol. 1 (New York: Kennedy Galleries, 1973), 149; and Peter Falk, The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, vol. 2 (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1988), 128. ↵

- William Walton, World’s Columbian Exhibition (Philadelphia: G. Barrie, 1893). ↵

- Annick Notter, The New World Museum: Visitor’s Guide (La Rochelle: Imprimerie Rochelaise, 2009). ↵

- Anna Bowman Dodd, “The Expatriates: the American Colony in Paris,” Bookman 25, no. 3 (May 1907): 266. ↵

- André (Jean André) Castaigne, Fata Morgana: A Romance of Art Student Life in Paris (New York: The Century Co., 1904), 7. ↵

- Ibid., 7. ↵

- Ibid., 8. ↵

- Ibid., 10. ↵

- Ibid., 11. ↵

- Ibid., 10–11. ↵

- Ibid., 11. ↵

- Ibid., 11. ↵

- Ibid., 11. ↵

- Castaigne, Fata Morgana, 10. On mythologies about Native American culture in modern America, see Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009). ↵

- Castaigne, Fata Morgana, 12. ↵

- Ibid., 15. ↵

- Ibid., 245. ↵

- Susan Grant, “Whistler’s Mother was Not Alone: French Government Acquisitions of American Paintings, 1871–1900,” Archives of American Art Journal 32, no. 3 (1992): 3, 8–9. ↵

- L. Verax, De l’envahissement de l’École des Beaux-Arts par les étrangers. Réclamations des élèves français (Paris: Librairie des Imprimeries Réunies, 1886), 17. See also Jill Jonnes, Eiffel’s Tower: And the World’s Fair Where Buffalo Bill Beguiled Paris, the Artists Quarreled, and Thomas Edison Became a Count (New York: Viking, 2009), 160. ↵

- H. Wayne Morgan, ed., An American Art Student in Paris: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1877–1882 (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1986), 12. ↵

- Castaigne, Fata Morgana, 3. ↵

- Ibid., 4. ↵

- Henry Tuckerman, Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists; Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America (New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1870), 425. On the appropriation of American Indians as the original Americans, see Shari Huhndorf, Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), 59. ↵

- Agathe Cabau, “L’Iconographie amérindienne aux salons parisiens et expositions universelles françaises (1781–1914)” (PhD diss., Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2014); Véronique Wiesinger et al., Sur le sentier de la découverte : rencontres franco-indiennes du XVIe au XXe Siècle/Crossing Paths: French-Indian Encounters XVIth to XXth Century, exh. cat. (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1992); and Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons, 186–92. ↵

About the Author(s): Emily C. Burns is Assistant Professor of Art History at Auburn University