From the Slipper of a Sylphide: A Box by Joseph Cornell

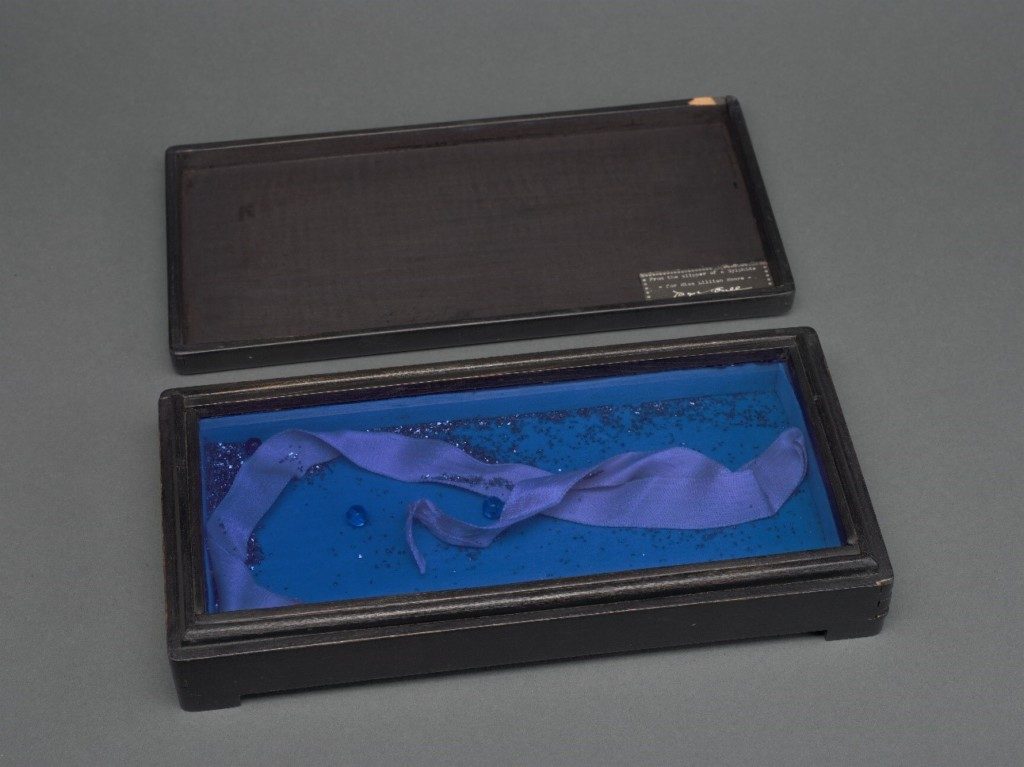

On June 22, 2017, I encountered a box by Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) that was new to me, and I believe new to the literature on the artist (figs. 1, 2). I was nearing the end of a short-term fellowship at the New York Public Library (NYPL) for the Performing Arts and had requested correspondence between Cornell and Lillian Moore (1911–1967), who was a dancer, dance historian, and former NYPL performing arts librarian.1 NYPL special collections librarian Jennifer Eberhardt, with whom I have worked for five years in the largely silent way specific to the archive, asked me if I was interested in Cornell and whether I would like to see their box by him.2 Yes, I was, and yes, I most definitely would. I wrote my master’s thesis on an issue of the magazine Dance Index by Cornell, and my dissertation includes a chapter on Cornell and his relationship to dance, so I searched my memory. I could remember no Cornell object connected to Moore, and I grew more excited when my quick internet searches also turned up nothing.

Eberhardt arranged for Arlene Yu, the collections manager for the Jerome Robbins Dance Division (and another recurrent fixture in my yearly bursts of research at the library), to bring the object to the reading room. In all my time in the collections, I had seen no reference to anything connected to Cornell other than a few letters. As I discovered, the Moore/Cornell correspondence was much more significant than it had seemed at first. Moore was not merely another dance aficionado who exchanged a few letters with the sympathetic artist. Cornell corresponded with many interested parties outside of the visual art world, but only a few resulted in anything more than niceties. He was not a scholar, and at least one dance writer found his idiosyncratic missives confusing even to the point of offense.3 Moore was an important historian whose writing likely influenced some of Cornell’s most significant work, and she directly inspired the ballet box that Yu carried across the reading room to the final row of quiet tables in the Lincoln Center library.

Yu set the box on the table, and my hands shook while I attempted to photograph it from every angle. She removed the lid and turned it over, revealing its title. I felt as I imagine Cornell must have in the first blushes of his love for the Romantic ballet, exhilarated by my proximity to the past. Like Cornell, my moment was facilitated by scholar-librarians who revealed a hidden story to me after years of quiet research. This encounter with art and dance history was only possible because of the generosity and attentiveness of Eberhardt and Yu. It was a new discovery, but neither truly new nor discovered. Cornell’s diaries are peppered with descriptions of exploring used bookstores and library collections, forever on the hunt for an authentic “bibelot” that would bring the past to him with multisensory vividness.4 I have only felt the unexpected thrill of discovery once: that June afternoon in the quiet archive of the New York Public Library, when I had unquestionably the most Cornellian moment of my life.

From the Slipper of a Sylphide (1949)

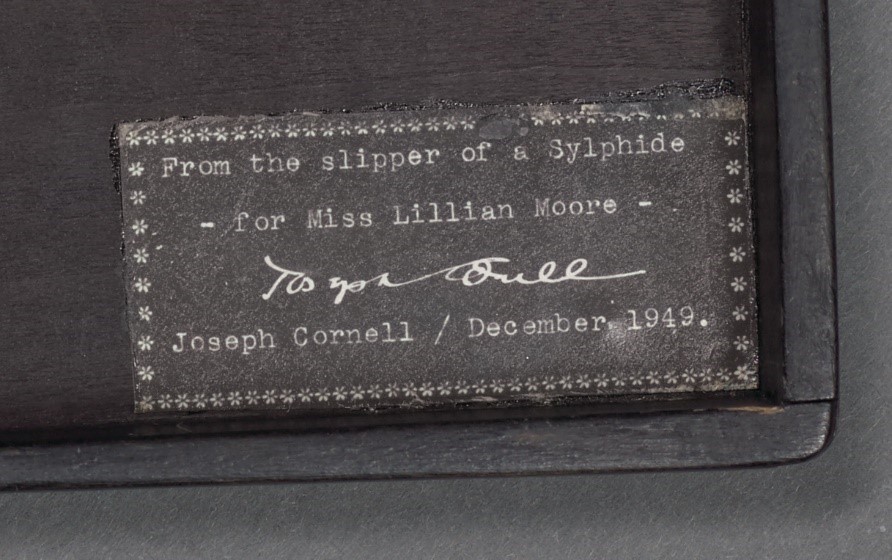

On New Year’s Day, 1950, when Cornell was forty-six years old and Moore was thirty-nine years old, he sent her a special package containing a “treasure” that should be “kept as you would . . . a piece of old china.”5This is not part of Moore’s catalogued correspondence, but Eberhardt was kind enough to forward me a scan of the letter after I left the library that evening. It had accompanied a black box, also uncatalogued, the size of a small book or a necklace case.6 A negative Photostat pasted in the bottom right corner of the underside of the lid gives the title of the object: “From the slipper of a Sylphide / —for Miss Lillian Moore—” (fig. 3). Cornell signs the label in script and types his name, clearly dating it: “December 1949.” In the custom-made joined box with smooth, curved corners, Cornell placed a length of ribbon, dyed blue to match the fabric lining of the box. The ribbon is pinned in place, wrapping around itself on the right side, arranged as though Cornell (or the Sylphide) draped it casually in a loose S-shaped arabesque. Marbles, small enough to be surrounded by the folds of the ribbon and the same deep blue as the fabric and ribbon, roll around the glass-enclosed space. When Yu picked up the box, the marbles moved into and out of the ribbon, settling in its folds. A small handful of loose blue glitter completes the composition, pooling in the left corner below the ribbon and speckling the bottom of the box like stars. The casket—a reliquary or jewel box—conceals its contents when closed.7 Moore could have displayed it in her dressing room and no one would have known it to be the work of the famous artist.

The box commemorates, nearly to the day, the ninth anniversary of Cornell’s relationship with Moore, encapsulating a bit of the sparkle that she had lent to him with her positive response to his early ballet work. In a now-lost letter sent in December of 1940, Moore inquired about the veracity of a “Grisi item” in one of the artist’s early solo shows at the Julien Levy Gallery.8 Cornell’s response survives in Moore’s papers and reveals how pleased he was that a serious historian believed his imagined relic may have been authentic. In the letter of December 29, 1940, he references her 1938 book, Artists of the Dance, which he held in his personal library, now at the Joseph Cornell Study Center.9 The Sylphide box also serves as a bookend to his interest in ballet. It marked the tenth anniversary of his relationship with ballet-as-subject, sparked by ballet and art patron Lincoln Kirstein and related to Moore in the 1940 letter.

While ballerinas would sometimes reappear in Cornell’s later collages, by 1950, he rarely felt the same motivation to create ballet boxes that he had in 1940 and 1941. As he tells Moore, “I have never made many of these miniatures, and with the exception of a couple things for the Ballets de Paris a few weeks ago, I’ve hardly done a new piece since before the war.”10 These two letters have become crucial markers of Cornell’s passion for the dance to me, concrete evidence of his effort to build relationships with the dance world through scholarship and the ways in which scholarship was the direct impetus for his work.

Cornell’s correspondence with Moore, which lasted until at least 1961 via occasional postcards and holiday greetings, echoed his multivalent interest in the ballet. It was serious and scholarly enough for Moore to inquire about whether he owned a particular sheet music cover to illustrate a biography written by her friend, the important dance historian Ivor Guest.11 It was sincere, inspired by Cornell’s own experiences of performance but also by his brushes with Romantic ephemera. And it was fleeting, dependent on the flash of inspiration of his trouvailles in Manhattan bookstores, the availability of the research material at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and area libraries, and the support of patrons and gallerists such as Kirstein and Levy.

Kirstein, Moore, and Cornell were all aware of the history of cooperation between the visual and dancing arts. Impresario Serge Diaghilev (1872–1929) and his Ballets Russes loomed large. The Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk model that Diaghilev adopted and that made the ballet into a phenomenon in the early twentieth century seemed the ultimate example of dance success.12 In the 1940s, visual artists and dance artists were struggling to achieve the balance that seemed to be “mutually beneficial” under Diaghilev and earlier collaborations.13 Spanish painter Joan Junyer (1904–1994) wrote about the ongoing debate for Dance Index in 1947:

[Ballet and painting have done] much for the other. Yet there is need today to bring painting for theatrical dancing to our own times. Scenic art conceived as a background or frame is now in the last phase of a glorious period. . . . There are cases of antagonism among the three collaborating arts [music, painting, and dance]. Sometimes painting disturbs the choreography, while at others it becomes incidental, obscured, or suppressed altogether. Yet a ballet in front of a black curtain with nondescript costumes is like a ballet without music.14

Such nondescript costumes and sets would be exactly what Kirstein-supported choreographer George Balanchine (1904–1983) adopted as he increasingly turned toward performances that evinced spare aesthetics and formalist movement, rejecting the theatrical and spectacular.15 Junyer goes on to describe romanticism as the greatest moment of cooperation between arts, when music, dance, and painting were equally united by the romantic impulse. Following Junyer, Cornell recreates the romantic as a memory of cooperation between the arts, one he saw might be fading away.

Perhaps it felt right to Cornell to focus on the ballerinas in bursts, since so many Romantic ballet scenarios revolve around the temporary apparition and demise of beautiful women. Perhaps Cornell also accepted the slipping interest in ballet in the world of visual art. MoMA closed its dance department when the curator George Amberg resigned in 1948. The museum promised supporters it would present more dance-themed shows, but it divested its research collections and did not return to the subject for an exhibition until 1966.16 Balanchine and other ballet choreographers embraced formalism while many modernist dancers moved toward nonnarrative expressionism.

At the same time that dance turned inward, Cornell, like much of the city’s art community, shifted from his neoromantic and surrealist mode toward abstraction, producing geometric “dovecotes” that would become vastly popular with art connoisseurs. As a result, his delicate ballet works have waned in the Cornell literature, eclipsed by the sharply focused boxes and evocative collage films that later artists and critics have loved. Bits of ribbon and glitter can seem hopelessly unserious; “inconsequential,” as Kirstein put it.17 But that very unseriousness was a commitment to the ephemeral, to the fragile, to objects and creatures that needed protection. Cornell created a facsimile of the romantic past to shield it as well as to contain it. With his gift to Balanchine-trained dancer Moore, he asked her to help him guard the treasure, to keep the Romantic ballet alive through his imaginary relics.

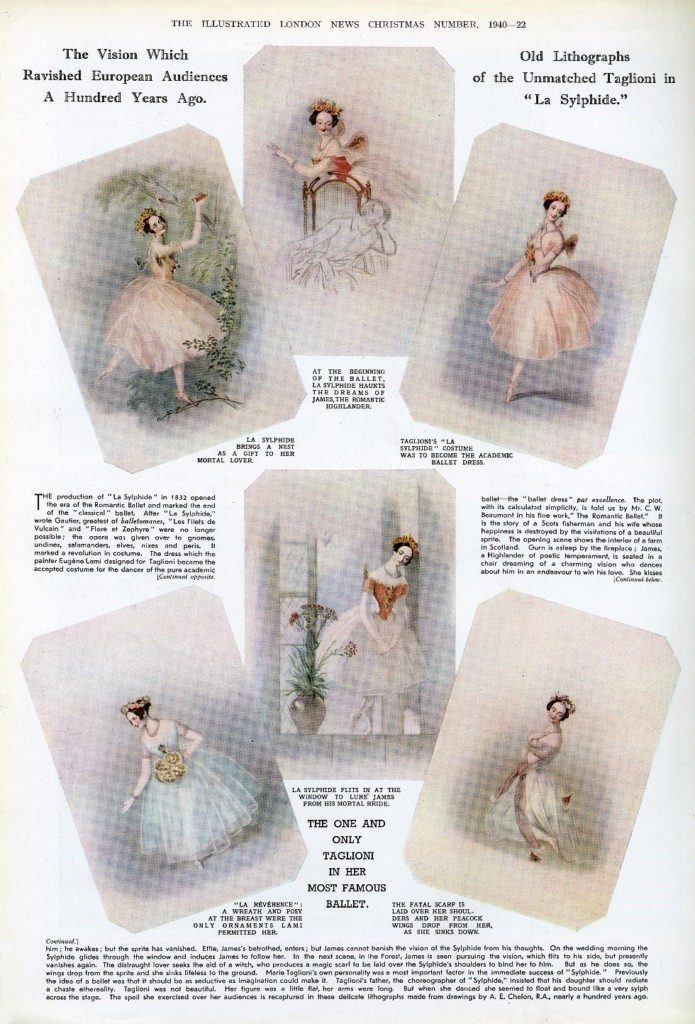

The 1949 reliquary memorializes a dying kind of narrative ballet through a particular figure, the tragic Sylphide. Since Cornell does not include an article—“La” or “Les”—the box can refer to both to the 1832 Romantic ballet La Sylphide, made famous by Marie Taglioni, and the 1907 ballet blanc Les Sylphides, choreographed by Mikhail Fokine. The foundational 1832 Romantic ballet was often illustrated in the prized lithographs which Cornell and other balletomanes collected (fig. 4).18 In some lithographs of Taglioni, the ballerina wears the flowing, ankle-revealing tutu that she popularized, with a blue ribbon emphasizing her waist.19 Moore would have immediately thought of the earlier dancer; she translated Taglioni’s letters for the magazine Dance in June 1945.20 A few issues of Dance survive in Cornell’s library and archives, including one from July 1945.21 Cornell expertly intertwines Taglioni and Moore, ballet women dedicated to bringing the past of the art to the present, connecting Cornell, as audience-artist, to performers in the nineteenth century and beyond. As was typical for him, he coalesces his referents. The Sylphide is Taglioni and Taglioni is the Sylphide, and perhaps all other dancers who performed her role are, too.

Cornell does not title the box “from the slipper of Taglioni,” or “from the slipper of a member of the corps-de-ballet,” but instead “from the slipper of a Sylphide;” in other words, from the slipper of the character or the creature herself. Cornell captured a physical remnant of the impossible, of a winged creature dancing on her toes. This mythological air spirit, who appears flirtatiously but ultimately never consummates a relationship with a Scottish fisherman, must have spoken to Cornell’s overlapping interests: the weather, the immaterial, the ephemeral, and the spiritual (fig. 5). The doubly resonant ribbon would have recalled Taglioni’s innovation, central to contemporary ballet technique: her semilegendary invention of dancing en pointe. The ribbon “from the slipper” would then represent an artifact of a foundational dancer and of the half-magical technical achievement of a nineteenth-century celebrity. Through Les Sylphides, the glittering box recalls the flowering of Russian ballet (both the past and present of dancing in the United States) and the spiritual successor to Taglioni, Anna Pavlova.22 What an appropriately thoughtful and historically informed gift for a dance historian.

Interesting Accidents

The space here to discuss how exactly Cornell’s relationship to Moore illuminates his interest in the dance is limited. The short 1950 letter is relevant to the gift box, but in the more important earlier letter, Cornell writes specifically and seriously about how and why he became interested in ballet as a subject. He tells Moore, “All of the interesting things in the art field that have happened to me have been accidents.”23 Despite Cornell’s feeling that his interest in dance was accidental, the letter and my research show that the artist’s interest in ballet was specifically guided by the resources available to him. Those resources spurred his art-making, and his “interest in dance grew,” supported by the arrival of many museum-approved and “pigeon-holed” prints, books, and miscellaneous objects.24 Cornell’s relationship to the MoMA Dance Archives and Lincoln Kirstein’s aggressive accumulation of the physical stuff of the dance in 1939 for those archives were primary drivers of Cornell’s dance work.25

The artist’s ballet work was accidental only in that he did not plan to devote himself to dance. In all other ways, his burgeoning balletomania was the result of the prolonged efforts of Kirstein and his circle to make dance a serious pursuit in the United States.26 Kirstein pulled Cornell into that project, hiring him to design covers and full issues of his scholarly magazine Dance Index.27 That magazine format would continue to interest Cornell until at least the mid-1950s, when he sent former Dance Index editor Donald Windham a design for an imagined magazine issue in the same distinctive size as that little magazine from the 1940s.28 Cornell loved the ephemeral and the accidental, and ballet seemed to him to be just those things. Ultimately, he was not very interested in the exigencies of actual ballet work.

From the Slipper of a Sylphide is a real ribbon with an unreal story, inspired by a real and specific history. How appropriate, then, for his authentic-yet-inauthentic work to have been lost—yet not lost—in an archive for some fifty years, shelved near the romantic treasures he emulated. Perhaps Cornell would have been pleased that someone should stumble across it there and experience the same flush of archival discovery that he had chased across the libraries and bookshops of that same city.

Cite this article: Elizabeth Welch, “From the Slipper of a Sylphide: A Box by Joseph Cornell,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1640.

PDF: Welch, From the Slipper of a Sylphide

Notes

- Lynn Matlock Brooks, “Lillian Moore (1911–1967),” Treasures, Dance Heritage Coalition, 2012, http://www.danceheritage.org/treasures/moore_essay_brooks.pdf. ↵

- I would like to thank Jennifer Eberhardt and Arlene Yu. Despite rarely exchanging more than ten words at a time in the intensity of my archive visits, I think of them both fondly as well as the rest of the staff at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library (NYPL). The rhythm of archival research entirely depends on their efficient expertise, so it is no exaggeration that I owe much of my academic career to their professionalism. ↵

- “I gather that the enclosed is a Christmas greeting to me which isn’t a Greeting {sic} to me at all, and to be returned. I’M {sic} still not quite clear about the reason for sending, or was it a joke? (If so one I find not in good taste and incomprehensible from you).” Cornell scribbled in his distinctive pencil, “too snippy to answer” (underline his). Marian Hannah Winter to Joseph Cornell, July 21, 1952, Box 4, Folder 11, Joseph Cornell Papers, 1804–1896, bulk 1939–1972, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/joseph-cornell-papers-5790/subseries-2-1/box-4-folder-11. ↵

- Cornell to Moore, December 29, 1940, Folder 98, Lillian Moore correspondence, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NYPL. ↵

- Cornell to Moore, January 1, 1950, uncatalogued item, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NYPL. ↵

- Joseph Cornell, From the Slipper of a Sylphide, 1949, uncatalogued item, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NYPL. ↵

- Cornell himself used the term “casket” to title one of his most famous works, Taglioni’s Jewel Casket (1940; Museum of Modern Art, New York). I use the term partly to gesture to the idea of both a reliquary and a jewelry box. Like Taglioni’s Jewel Casket and Homage to the Romantic Ballet (1942; Art Institute of Chicago), the box is designed to be displayed on a flat surface, not hung like a shadowbox. Unlike those two works, From the Slipper of a Sylphide is not hinged. ↵

- The “Grisi item” is perhaps related to an object now held by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art: a bouquet of dried flowers tucked inside an envelope sent to Cornell with Lincoln Kirstein’s address on the back and postmarked December 29, 1940. In other words, Kirstein sent it to Cornell on the same day that Cornell wrote a letter to Moore referencing a Grisi “bouquet.” It may have been a text-based pamphlet, a precursor to his work for Dance Index. Cornell referred to his text- and image-mixing photomontages as “bouquets” and mentions an “album” sold to “Mrs. Cole Porter” in the same letter. Grisi is Carlotta Grisi, the Italian Romantic ballerina who appears in several of Cornell’s ballet works. I discuss this letter and what the object may have been much more fully in my dissertation. Dried bouquet and envelope from Lincoln Kirstein, December 29, 1940, Box 18, Folder 25, Joseph Cornell Papers, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/joseph-cornell-papers-5790/series-5/box-18-folder-25; and Cornell to Moore, December 29, 1940, Lillian Moore correspondence. ↵

- Lillian Moore, Artists of the Dance (New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell Company, 1938), Joseph Cornell Study Center, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Thanks is owed to Anna Rimel of the Joseph Cornell Study Center for sharing the in-process cataloguing of Cornell’s personal library with me. Moore’s book includes sections dedicated to all the major dance stars to whom Cornell devoted works. Her lucid, readable history may have been a primary inspiration for some of the most important Cornell works in the early 1940s, which I discuss in my dissertation. ↵

- Cornell to Moore, January 1, 1950, Lillian Moore Papers. ↵

- Moore to Cornell, May 8, 1955, Box 3, Folder 15, Joseph Cornell Papers, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/joseph-cornell-papers-5790/subseries-2-1/box-3-folder-15. ↵

- Many scholars have tackled the relationship between dance and the visual arts under the Ballets Russes. One of the most significant contributions is by Juliet Bellow. She makes a sweeping argument about inter-media collaboration in her book Modernism on Stage: The Ballets Russes and the Parisian Avant-Garde (Burlington: Ashgate Press, 2013). Lynn Garafola’s work from a dance studies perspective is a foundational history of the Ballets Russes and its cultural impact. Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). ↵

- Joan Junyer, “On Dance,” Dance Index 6, no. 7 (1947): 147. ↵

- Junyer, 147. ↵

- Tamara Tomic-Vajagic dates this transition to nearly the same time as the box and Cornell’s rejection of dance as subject: the sparer 1951 revival of the 1946 ballet Four Temperaments. Tomic-Vajagic, “The Dancer at Work: The Aesthetic and Politics of Practice Clothes and Leotard Costumes in Ballet Performance,” Scene 2, nos.1 and 2 (October 2014): 91. ↵

- Monroe Wheeler to Elizabeth P. Barrett, William Van Lennep, George Freedley, and Lincoln Kirstein, June 11, 1948, Series 1, Folder 5, Dance Archives, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Archives, New York; also the exhibition “Chagall: Aleko,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 14,1966–February 26, 1967, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2589?locale=en. ↵

- Lincoln Kirstein, “Comment,” Dance Index 5, no. 6 (June 1946): 135. ↵

- For the most extensive published work on Cornell as a balletomane, see Sandra Leonard Starr, Joseph Cornell and the Ballet (New York: Castelli, Feigen, Corcoran, 1983). Starr rigorously and thoughtfully describes Cornell’s relationship to the ballet through analysis of some of his more famous ballet works. More recently, Analisa Leppanen-Guerra has discussed Cornell’s interest in dance as a form of pacifism in “Immortal Dancers: Joseph Cornell’s Pacifism During the Second World War,” in Jane Dini, ed., Dance: American Art, 1830–1960, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts; London and New Haven: Yale University Press: 2016), 265–80. I connect Cornell’s personal exploration to the specific history of the ballet boom in 1940s New York in my dissertation. ↵

- Cornell could have seen some of these in the exhibition Preview: Dance Archives at the Museum of Modern Art, March 6–April 7, 1940. Installation photograph, dance archives, series 1, folder 14, MoMA Archives, New York. George Chaffee also documented romantic lithographs in two issues of Dance Index. Cornell designed the cover “montage,” Parker Sisters, for the February 1942 issue, and Chaffee connects the “Romantic montage” cover of the December 1942 issue to Cornell’s style. See Chaffee, “American Romantic Ballet Music Prints,” Dance Index 1, no. 12 (December 1942): 203, and “A Chart to the American Souvenir Lithographs of the Romantic Ballet 1825–1875,” Dance Index 1, no. 2 (February 1942). ↵

- Lillian Moore, “The Sylphide and Her Letters,” Dance 19 (June 1945): 30–31. ↵

- Dance 19, no. 7 (July 1945), Box 14, Folder 15, Joseph Cornell Papers, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/joseph-cornell-papers-5790/subseries-4-3/box-14-folder-15. ↵

- Cornell connects the two artists directly in his notes. I maintain his strikethroughs to show his editing that emphasized Taglioni’s historical importance. “Is it any wonder, then, that one in our generation

to revivethe whoapproachfollowed so closely thestepspointes of the original Sylphide, should manifest such a predilection for kindred roles such as Pavlova did in Dragon Fly.” Handwritten, undated note, Box 26, Folder 2, Joseph Cornell Papers, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/joseph-cornell-papers-5790/subseries-4-2/box-26-folder-2. ↵ - Cornell to Moore, December 29, 1940, Lillian Moore correspondence. ↵

- Cornell to Moore, December 29, 1940. ↵

- I explain this much more extensively in my dissertation. Kirstein sent Paul Magriel to France in 1939 to acquire the collection that formed the core of MoMA’s Dance Archives. Paul Magriel then became the librarian in charge of the collection and co-founded Dance Index with Kirstein. Cornell tells Moore that he acquired dance films for Kirstein around the same time and attributes his interest in dance to that relationship. Elizabeth Welch, “Looking at Bodies: Dance Index, the Visual Arts, and the Image of Performance in 1940s” (unpublished PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, April 2018) and Cornell to Moore, December 29, 1940. ↵

- Prospectus for Dance Index, “Dance Index: A New Magazine Devoted to Dancing,”1941, Box 12, Folder 25, Joseph Cornell Papers, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/joseph-cornell-papers-5790/subseries-4-3/box-12-folder-25. ↵

- Cornell designed four full issues of Dance Index. They are: “Le Quatuor dansè à Londres par Taglioni, Charlotte Grisi, Cerrito et Fanny Elsler,” Dance Index 3, nos. 7, 8 (July/August 1944); Hans Christian Andersen,” Dance Index 4, no. 9 (September 1945); “Clowns, Elephants and Ballerinas,” Dance Index 5, no. 6 (June 1946); “Americana: Romantic Ballet,” Dance Index 6, no. 9 (1947). He designed the cover “montages” for the following ten issues: volume 1, no. 1 (January 1942); volume 1, no. 2 (February 1942); volume 1, no. 3 (March 1942); volume 1, no. 6 (June 1942); volume 2, no. 4 (April 1943); volume 3, nos. 4, 5, 6 (April/May/June 1944); volume 3, nos. 9, 10, 11 (September/October/November 1944); volume 4, no. 5 (May 1945); volume 4, nos. 6, 7, 8 (June/July/August 1945); volume 4, no. 10 (October 1945). ↵

- Joseph Cornell, unpublished magazine designs, Box 10, Folder 2, Donald Windham and Sandy Campbell Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven. ↵

About the Author(s): Elizabeth Welch is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas at Austin.