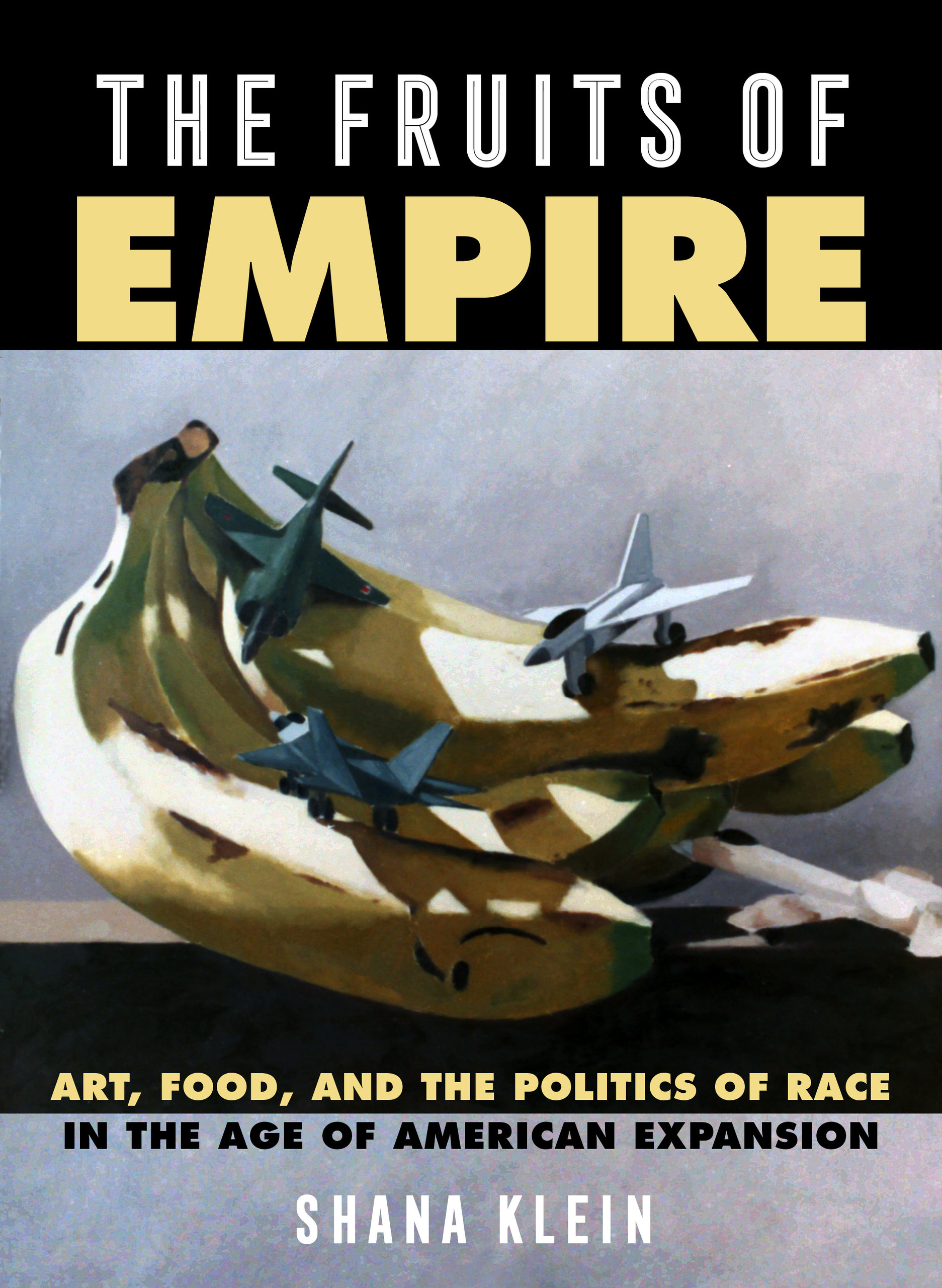

The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion

PDF: Elder, review of Fruits of Empire

The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion

by Shana Klein

by Shana Klein

Oakland: University of California Press, 2020. 264 pp.; 45 color illus., 17 b/w illus. Hardcover $65.00 (9780520296398)

In the wake of the Civil War, the citizenry, history, and economy of the United States were in flux. The newly reunified country had to integrate into the body politic two radically different populations: white citizens who had rebelled against the state and Black Southerners who had been born into slavery and were now free. At the same time, the nation looked to its Western territories to locate a shared past as well as to islands in the Atlantic and the Pacific that could help expand the country’s economic base and labor force. The era in which these developments took place—the 1860s through the 1940s—witnessed the failed promises of Reconstruction, the rise of Jim Crow laws, adoption of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the Spanish-American War, the American-Philippine War, and the forced annexation of Hawai‘i. The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Era of American Expansion focuses on this pivotal time in the nation’s domestic and international relations. Rather than explicit depictions of these discriminatory policies and exploitative incursions, however, Shana Klein invites us to consider a seemingly negligible and humble subject: images of fruit.

Over the course of five chapters—each dedicated to a different pome—Klein unequivocally demonstrates that the verbal and visual discourses around fruit were a critical means by which artists, corporations, and the white public negotiated who and what was “American.” Grapes, oranges, watermelons, bananas, and pineapples, as well as representations of them, were intimately tied to mainstream perceptions of the nation’s past, its diverse populations, and the country’s relationship to islands in the Atlantic and the Pacific. Advertisements and trade cards; tableware and flatware; commercial and documentary photography; and still-life paintings by familiar, recuperated, and surprising names reflected and shaped how the general public perceived both the geographically peripheral territories where these fruits grew and the people who harvested, commodified, and consumed them. During the tumultuous era in which the nation’s economy and population rapidly diversified, images of fruit and objects bearing them were a means through which individuals and corporations forged both cultural stereotypes and cultural norms.

Establishing a critical contribution of the book, the first chapter on grapes offers an art history from the margins. Both in terms of its geographical focus and the visual material Klein tackles, “Westward the Star of Empire: California Grapes and Western Expansion” departs from traditional narratives of American art. Her story begins not with Gilded-Age painting and sculpture in the Northeast but in California in the post–Civil War era, when wine makers used world’s fairs to assert the sophistication and historicity, but also the whiteness, of the United States vis-à-vis Europe. In a bid to elevate Europeans’ perceptions of the California wine industry and the United States in general, exhibition displays and ephemera representing them bypassed the region’s relatively recent connection to Mexico (as well as to the Native and Chinese laborers on which the industry had, respectively, relied in the past and the present) and instead touted its prior relationship to Spain and Spanish missionary efforts. California-based still-life painters made similar claims in their work. As the state strove to establish its place in the relatively newly reunified nation and the nation worked to establish its place on the world stage, vintners and artists crafted grapes into a symbol of “civilization.”

Shifting to the post-Reconstruction South, chapter 2 addresses artistic and commercial depictions of the Florida orange industry. Klein argues that in the wake of abolition, paintings, photographs, and popular media depicting oranges and orange groves worked to rehabilitate Northern perceptions of the economic potential of the South and also to facilitate Northern interventionism and migration to the region. Oranges helped frame Florida as a land of abundance and opportunity. Klein attends to the significance of this campaign for white women and Black men, who were among the audiences for these images. Although this chapter addresses objects of material and visual culture, it may be of particular interest to art historians for its discussions of several well-known artists and one unexpected name. Klein addresses the still lifes of oranges that Martin Johnson Heade created under the auspices of entrepreneur Henry Flagler and Henry Ossawa Tanner’s melancholic landscapes of Florida orange groves, which she argues register the region’s growing hostility to African Americans in the Jim Crow era. But the chapter’s major art-historical contribution is its attention to author Harriet Beecher Stowe’s still-life practice. Herself a New England transplant, Stowe bought an orange grove in Mandarin, Florida, where she cultivated and painted its fruits—selling both the harvest and her artworks in an attempt to advertise the state’s potential to be “civilized,” or, in other words, Northernized.

Chapter 3 explains how and why commercial outfits and painters used watermelons as a means to denigrate African Americans. Indigenous to Africa and easily grown on enslaved people’s private plots, the watermelon was—in the antebellum era—a symbol of Black agency and pride. As Black men in particular gained rights to land and political representation, white image makers expressed their anxieties about the shifting social order via images of Black men and boys either ravenously devouring the fruit or assuming its form. This imagery appeared on trade cards for various food-adjacent businesses, in genre and still-life paintings, and in a variety of media as collectible souvenirs. All of these objects promulgated and normalized this vicious stereotype both in the private and public spheres. Laudably, the chapter also addresses historic and contemporary works of art that undermine it—works such as Charles Ethan Porter’s Broken Watermelon and Valerie Hagerty’s Alternate Histories, which visualize and counter the stereotype’s violence. These welcome complements to the discussion of derogatory uses of watermelon imagery offer ways in which other scholars could productively expand on Klein’s project. Why did this historic imagery and the pernicious stereotype that it helped circulate become generative for visual artists at the turn of the twenty-first century? And, are there other instances in which representatives of the populations that mainstream images of fruit sought to marginalize contested their characterization by visual or discursive means?

In chapter 4, Klein focuses on the banana, which grows in Central America and the Caribbean and is imported to the United States. To build a domestic consumer base for the exotic product, the United Fruit Company (UFC) exploited existing strategies that had tempered the banana’s association with the tropics and affiliated it, instead, with progress and modernity. The end of the nineteenth century witnessed haphazard attempts to glamorize or at least normalize banana consumption. At the turn of the century, though, explicitly borrowing interventionist strategies from the Reconstruction era, UFC launched advertising and cookbook campaigns that framed itself as a “civilizing force” in the tropics and that positioned the banana as an emblem of refinement. Bracketing political realities in places like Guatemala, where UFC grew and harvested the fruit (and supported a Central Intelligence Agency–backed coup in 1954), the company’s marketing used modernist strategies to depict bananas in the United States home. In this chapter, too, Klein invokes contemporary works of art that address the politics that UFC’s advertising campaigns strategically ignored.

The focus of chapter 5 is the pineapple, which the Dole Corporation cultivated in Hawai‘I, rightly anticipating that the United States would support and facilitate incursions into the region. As Klein details, “Leaders of the Dole Hawaiian Pineapple Company campaigned for Hawaiian statehood in the 1950s, as [they] had done for annexation in the 1890s, when the United States sought to incorporate the Hawaiian Islands for their militaristic and economic advantages” (139). These campaigns took place in the halls of government and also in the pages of American magazines, where Dole used advertising to attempt to mitigate the racial anxieties that white Americans had about Hawai‘i’s Indigenous and immigrant populations. By minimizing, “sanitizing,” sexualizing, or altogether eliminating people of color, the corporation’s marketing materials represented Hawai‘i, the pineapple industry, and Dole’s products as ripe (it had to be done!) for the American market. Of particular note is Klein’s discussion of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work for the corporation and the ways in which the artist and Dole negotiated their competing perspectives on the labor debates at its Hawaiian plantation. Although addressed in recent exhibitions, this material benefits from being located within a study about the politics of food imagery, where it lends further weight to other scholarly efforts to recuperate O’Keeffe’s investment in contemporary social issues.1

Published for the University of California Press’s California Studies in Food and Culture series, The Fruits of Empire offers an engaging cultural history of grapes, oranges, watermelons, bananas, and pineapples in the United States that, as Klein notes, contributes to food studies a greater focus on, and attention to, the objects of visual and material culture. Throughout the book, she highlights the ways in which her study builds on the work of scholars in this growing field, and her conclusion addresses “new directions in scholarship on food in American art,” pointing to several other crops and commodities whose depictions deserve comparable attention. Delving deep into the singular histories of individual fruits, Klein makes a strong and convincing case for taking seriously the ways in which individuals and corporations used and pictured food to serve their own professional and economic interests. That said, given the book’s focus on visual culture, it would have benefited from a larger image program. In every chapter, several images are discussed and described at length that go unillustrated, and their inclusion would have helped to advance and solidify the author’s premise that the politics of fruit crystallize in representations of it. However, a larger criticism (which is also a compliment) is that I, as an art historian like Klein, would have loved to see her explore further the book’s many contributions to our field, which differ from what readers might expect.

As the book’s topic is images of fruit, we might anticipate that the book’s chief interlocutors would be studies of American still-life painting. In the introduction, Klein herself locates the project within this context. But The Fruits of Empire actually sits more productively beside other studies of industry and empire between the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement. In terms of industry, the book could easily be placed into conversation with Vanessa Mielke Schulman’s Work Sights: The Visual Culture of Industry in Nineteenth-Century America (University of Massachusetts Press, 2015). Both projects attend to the ways images about industry and mass-produced images themselves shaped ideas about modernity and difference after the Civil War. Fruits of Empire also complements Vivien Green Fryd’s Art and Empire: The Politics of Ethnicity in the United States Capitol, 1815–1860 (Ohio University Press, 2001) as well as a number of slated academic and museum publications on art and US imperialism.2 Indeed, it is exciting to think about how the combined force of all this scholarship will reorient understandings of the so-called Gilded Age and retrieve the global character and complexity of American art and culture in this era.

Americanists will be able to bring this context and framework to The Fruits of Empire and will readily see the role that it can play in their courses and research. But the book’s strength also rests in its accessibility and relevance to readers well beyond the classroom. A captivating read, it offers clear insight into the growth of the fruit industry and the many ways in which its attendant images sowed the seeds for the rhetorical and physical violence against Asian, Black, Latinx, and women-identified people that continues to haunt the United States to this day.

Cite this article: Nika Elder, review of The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion, by Shana Klein, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17484.

Notes

- Recent publications of O’Keeffe’s Hawaiian paintings include Theresa Papanikolas and Joana L. Groarke, Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of Hawai‘i (Munich: Prestel, 2018); Theresa Papanikolas, Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams: The Hawai‘i Pictures (Honolulu: Honolulu Museum of Art, 2013). For a study that addresses O’Keeffe’s awareness of, and interest in, the representation and politics of World War II, see Sascha Scott, “Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘Black Place,’” Art Bulletin 101, no. 3 (July 2019): 88–114. ↵

- Forthcoming books on this topic include Maggie Cao, Painting and the Making of American Empire, 1830–1989 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming); Taìna Caragol, Kate Clarke Lemay, and Carolina Maestre, eds., 1898: Visual Culture and U.S. Imperialism in the Caribbean and Pacific (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023). ↵

About the Author(s): Nika Elder is Assistant Professor at American University.