Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern

Curated by: Wanda M. Corn

Exhibition schedule: Cleveland Museum of Art, November 21, 2018–March 3, 2019; Wichita Art Museum, March 29–June 23 2019; Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, July 19–October 20, 2019; Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL, November 22, 2019–February 4, 2020

Exhibition catalogue: Wanda M. Corn, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, exh. cat. New York: Delmonico Books/Prestel, 2017. 320 pp.; 217 color illus.; 112 b/w illus. Hardcover $60.00 (ISBN: 9783791356013)

In 1935, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1996) visited the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) for the first time when her painting Red Maple, Lake George (1926) was exhibited there. Two years later, O’Keeffe was invited to participate as a juror for their May Show, an annual museum event inaugurated in 1919 for regional artists to exhibit and sell their work.1 Earlier in the decade, the museum purchased O’Keeffe’s White Flower (1930), and records indicate that the CMA may well be the first museum to acquire one of her flower paintings. O’Keeffe’s affection for the CMA had so been fostered, and at her death, she bequeathed five canvases to the museum. Late this past fall, O’Keeffe posthumously returned to Cleveland with Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern. The exhibition makes intriguing connections between O’Keeffe’s art, wardrobe, and public persona, which curator Wanda Corn dubs a “holistic aesthetic.”2

The exhibition originated at the Brooklyn Museum and traveled to two other venues from 2017 to 2018, and Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern recently reopened for a second tour at four additional museums, beginning with the CMA.3 The host curator in Cleveland, Mark Cole, worked closely with Corn to decide which objects would best fit the footprint of the CMA exhibition space and still preserve the thesis of the show, with about two-thirds of the works from Brooklyn selected from the checklist for inclusion. The CMA flower painting Morning Glory with Black (1926), purchased by a Cleveland art collector in the 1920s from Alfred Stieglitz’s third and last gallery, An American Place, and donated to the museum in 1958, was added to the presentation and will travel to the remaining venues. Two of the five canvases O’Keeffe gifted to the museum appear in the Cleveland iteration of Living Modern, both on Southwestern themes, giving the exhibition even more of a hometown touch. Paintings such as these are accompanied by works on paper and two sculptures by O’Keeffe, but the show emphatically privileges the remarkable archive that O’Keeffe preserved in her closets.

Visitors are introduced to the guiding concept of the exhibition by four stylistically related objects showcased at the beginning of the installation: two abstract paintings by O’Keeffe, a favorite “Chute” dress by Italian designer Emilio Pucci, and a photograph of the artist wearing a sharply cut collared shirt, one of several in the show taken by Stieglitz, her husband (fig. 1). All feature a prominent “v” shape—thereby allowing viewers an initial opportunity to trace the continuity between elements in O’Keeffe’s art and life. Stieglitz’s photograph offers the earliest example of how important formal portrait photographs are to the exhibition: as an aid to help date garments, to understand which clothes O’Keeffe favored for different audiences and how she wore them, and to reveal how carefully O’Keeffe presented herself to the world over her extensive career.

After this opening prologue, the show is organized chronologically, for the most part, in four rooms, more deeply demonstrating how O’Keeffe deliberately crafted a unified aesthetic, with the first gallery highlighting O’Keeffe’s early years and life in Manhattan. Two high school photographs and an oil portrait of a twenty-year-old O’Keeffe, painted by Art Students League classmate Eugene Speicher (1908; Art Students League), establish her independent thinking vis-à-vis her stylistically progressive manner of dress and severe presentation as a young woman. After she moved from Texas to Manhattan, O’Keeffe adopted the mostly monochromatic and streamlined black-and-white wardrobe for which she is well recognized, and so one particular garment comes as something of a surprise. O’Keeffe’s final skyscraper painting (1932; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC) is deliberately paired with a silk kimono-style evening coat possibly designed by the artist (fig. 2). The coat boasts a partially hand-painted lining in a number of colorful shades beginning at the hem, and is conspicuously in accord with the columnar form of the soaring, multi-hued buildings depicted in her well-known canvas.

The second room focuses on O’Keeffe’s clothing during her summers at Lake George, the Stieglitz family retreat in upstate New York. Three short-sleeved white linen blouses that hang side-by-side are particularly striking, in bold contrast against a black accent wall (fig. 3). Here visitors discover that there is not only seriality in O’Keeffe’s paintings, but in her mode of dress as well (later, a hanging row of five different colored wrap dresses from the late 1950s to the 1970s confirms O’Keeffe’s penchant for multiples in the clothes she favored). The delicate ornamentation at the neckline of one blouse, constructed by dozens of tiny, handsewn pin tucks believed to be stitched by the artist herself, conjures the veins of leaves in a contemporaneous painting hanging nearby, as well as two pairs of shoes decorated with a leaf motif that further connect with her interest in nature. This gallery closes with Arnold Newman’s well-known photograph of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, nearly fused as one by the black capes that appear to encase and blend their bodies together (1944). The composition of the photograph has in the past lent itself to a reading of the pair as missionaries united for the cause of modern art or as an exploration of the artists’ differing personalities: Stieglitz gregarious and garrulous in opposition to O’Keeffe’s meditative and quiet demeanor. But that the two face in different directions may also be an allusion to the strains in their relationship, and the photograph, in that sense, subtly announces what comes in the next gallery: O’Keeffe’s evolving style as she makes a life in New Mexico without her husband.

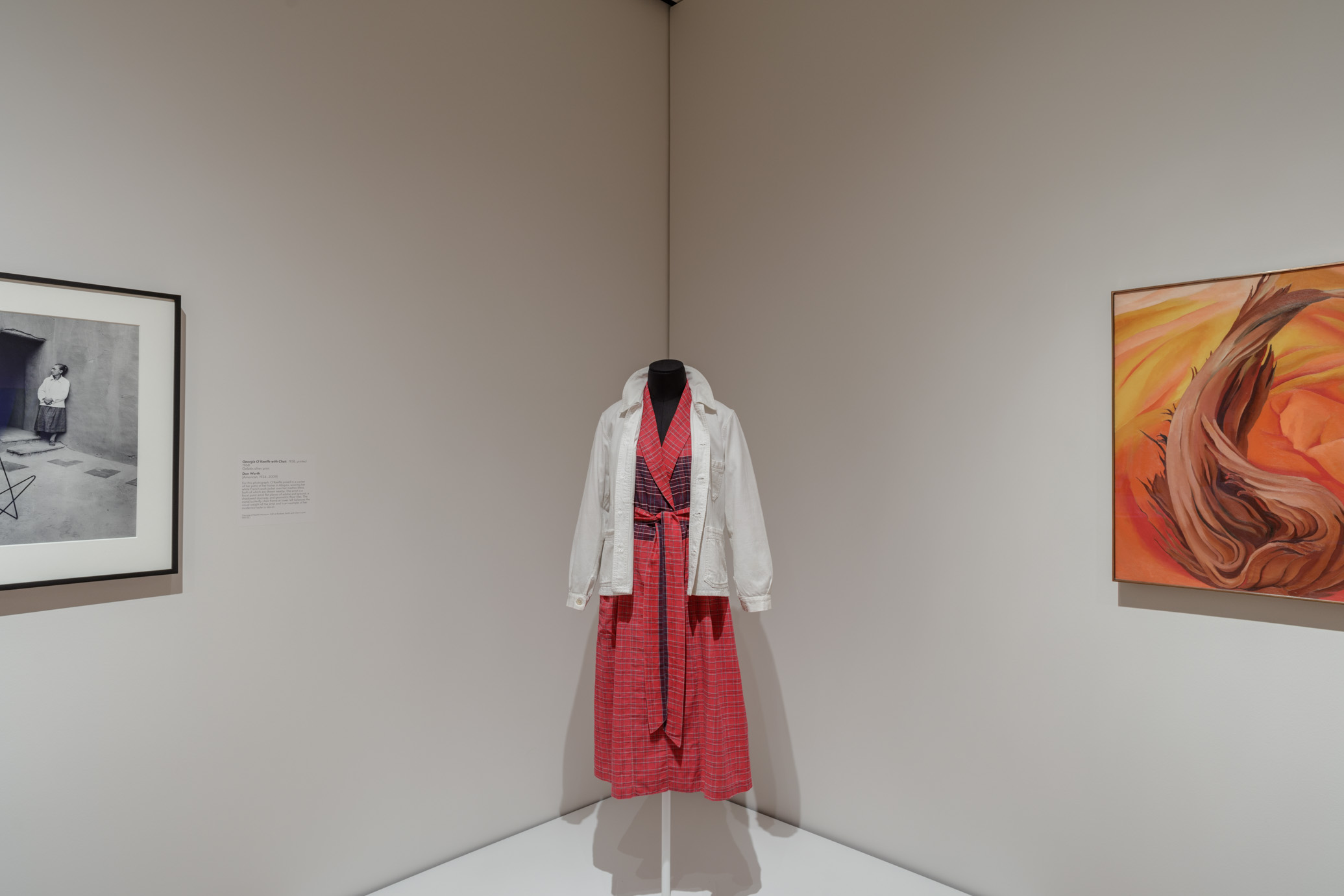

Visitors entering the generous third gallery are immediately struck by how O’Keeffe’s new surroundings stimulated a change in color palette for her art as well as her garments. At times she would cast aside the signature tailored black suits, unornamented dresses, and androgynous capes that she favored in Manhattan for shades of blue denim and even a red, belted madras dress with purple accents that she may have designed and made (fig. 4). Yet she still chose to wear a minimalist gaucho hat, carefully avoiding the curves and fringes of a typical cowboy hat. Photographs of O’Keeffe by Ansel Adams show her more relaxed in her Southwestern desert environment (1937, 1938) than when pictured in urban New York. Unsurprisingly, O’Keeffe was attracted to painting simplified adobe architecture, which meshed with her stark personal style.

For most, O’Keeffe’s lifelong interest in East Asian cultures is the least familiar aspect of her oeuvre. She owned a substantial collection of books on Japanese and Chinese subjects, including calligraphy, art, and philosophy, and in 1959 and 1960, she traveled to Asia for an extensive period of time. While there she fed her love of kimonos (she owned at least twenty at her death), had clothes tailor-made in Hong Kong, and bought garments off the rack. O’Keeffe only created three sculptural works, and the gallery devoted to her Asian influences features Abstraction (1946, cast 1979–80; Georgia O’Keeffe Museum), one of the two sculptures in the show. Abstraction sits in front of four gorgeous kimonos, one with curvilinear patterning in concert with the spiral form of the white-lacquered bronze sculpture. Flanking the sculpture are two delicate, calligraphic paintings inspired by her affinity for all things Asian (fig. 5).

The final gallery addresses O’Keeffe’s celebrity and relies heavily on a variety of photographs taken over several decades to convey the varied ways she captured the American imagination. Here we also see that the cool, deliberate demeanor honed in O’Keeffe’s early presentations stretch through to the very end of her life. The greatest indication of O’Keeffe’s celebrity may not be that she posed for more than forty professional photographers over half a century, yielding about five hundred images, or her appearance on the cover of Life magazine (1968); instead, it could be celebrity-obsessed Andy Warhol’s shimmering diamond dust silkscreen (c. 1980), based on a series of Polaroids he had taken of O’Keeffe during one of their visits, that puts the artist in the company of Elvis and Marilyn, and it is this work that concludes the exhibition.

In an exceptionally thorough and abundantly illustrated catalogue that amplifies the exhibition themes, Corn links O’Keeffe to Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, whose art and fashion sense similarly and strongly intersect, and whose celebrity status in the art world rivals her American counterpart. Corn further compares O’Keeffe’s interrelated manner of living with other art world luminaries such as Gertrude Stein and James McNeill Whistler. While the show was hanging in Cleveland, the Nevada Museum of Art mounted the first major retrospective of photographer Anne Brigman, and there is an analogy to be made there as well. Much less known than her heavily studied contemporary, Brigman (1869–1950) was also a long-lived, childless woman struggling in a male-dominated art world, whose work was pigeonholed by her gender.4 Brigman provides a counterpoint to O’Keeffe; while O’Keeffe was being photographed nude by her husband, at times aligned with nature or dressed like a monk in New York City, Brigman deliberately presented herself nude in the California wilderness in dozens of staged self-portraits. She was muse to no one but herself.

To all outward appearances, Brigman took more agency in her life and of her body than did O’Keeffe, but Living Modern refutes that notion. Much has been said about Stieglitz’s commodification of O’Keeffe’s body and art, but the exhibition makes a strong case that while O’Keeffe’s resistance to her husband’s gendered classification of her art was mostly fruitless, she often controlled her presentation through her wardrobe; the methodical way she dressed, posed, and orchestrated the copious photographs taken of her; and how she designed her living spaces. One crucial element, which Corn discusses in depth in the catalogue but could only be suggested in the exhibition, is how assiduously O’Keeffe integrated the decor of her domestic spaces with her larger artistic program—hence the apt umbrella term “living modern.” Beyond offering an original and refreshing perspective on a much-parsed artist, Corn, whose scholarship has been groundbreaking for the field of American art, provides yet another new interpretative paradigm for future studies and exhibitions on any number of topics by so compellingly demonstrating the vitality of material culture as a means to increase our understanding of an artist’s work and way of being.

July 10, 2019: An earlier version of this article incorrectly cited the title of the exhibition catalogue.

Cite this article: Samantha Baskind, review of Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, Cleveland Museum of Art, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1708.

PDF: Baskind, review of Georgia O’Keeffe

Notes

- Leslie Cade, “O’Keeffe and the May Show,” Cleveland Art 59, no. 1 (January/February 2019): 15. A small display case of May Show documents and photographs was on view in the CMA library during the run of the exhibition. ↵

- Wanda M. Corn, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, exh. cat. (New York: Delmonico Books/Prestel, 2017), 11. ↵

- Brooklyn Museum, March 3–July 23, 2017; Reynolda House Museum of American Art, August 18–November 19, 2017; and Peabody Essex Museum, December 16, 2017–April 8, 2018. ↵

- Anne M. Wolfe, et al, Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018). ↵

About the Author(s): Samantha Baskind is Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University