Iconoclasm on Paper: Resistance in the Pages of Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, 1849

Author’s note1 and content warning: In keeping with this article’s consideration of the ethical implications of looking at and disseminating images of torture and subjection, we have decided to screen some images in the web version so that readers can choose whether to view them or not. Clicking on the brief title will open the image in another window. In the pdf version, all images are visible. This article also employs discursive captions in order to reflect the layers of mediation, alteration, and labor inherent within the images discussed.

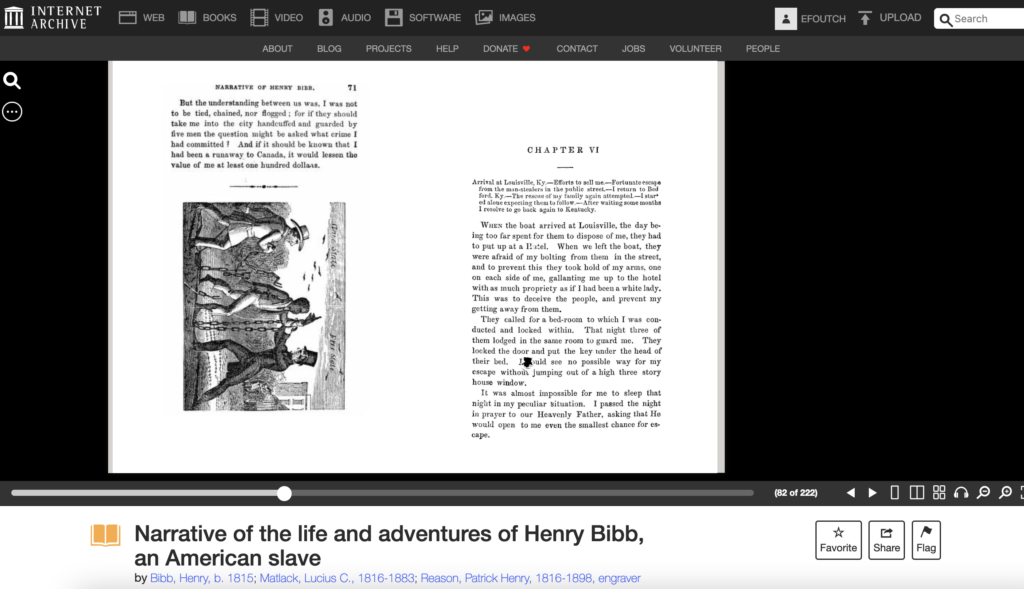

Discussions of iconoclasm frequently focus on the destruction or violence wrought upon large-scale works—life-size paintings, larger-than-life sculptures, or massive altarpieces—assaulted by a group or individual brandishing damaging tools or instruments, such as ropes, swords, or hatchets. In a US context, scenes of iconoclasm have often featured rowdy crowds wrestling with unwieldy objects: we might think of patriots in New York’s Bowling Green, tearing down the equestrian statue of King George III, or formerly enslaved men and women attacking the family portraits of Southern enslavers; more recently, the spring 2003 footage of US Marines toppling the monumental statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad comes to mind.2 This research note considers a quieter kind of iconoclasm, one that nonetheless offers important material evidence of the power of images and of readers’ agency: a defaced book, now in the collection of Emory University Libraries and viewable online via the Internet Archive.3 The pages of this book are part of a long-standing tradition of conscientious iconoclasm, in which altering or damaging a picture or object constitutes a considered form of political protest, while they also provoke further reflection upon questions about the ethics of viewing or showing scenes of pain and suffering. Their dissemination via digitization further complicates these questions.

In the spring of 2015, I taught a class on the American Civil War and its reverberations in the art and material culture of the United States. To foreground the voices of Black authors and artists, I selected the 1849 Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave as a primary source for students to study, using a scanned edition of the volume that was easy to access online. The book offers a study in contrasts between the ways in which enslaved people were portrayed in much media of the time—generic representations that depicted them as economic commodities—versus Bibb’s individual experiences and perspective. While the text foregrounds Bibb’s subjectivity in relating his repeated attempts at self-liberation, the accompanying wood engravings are, in many instances, reprinted from other antislavery publications, evoking in their very familiarity Saidiya Hartman’s searing analysis of “scenes of subjection.”4

Clicking through the pages of the text brings us to an archetypal image of a slave auction that depicts a heartrending scene (fig. 1).5 A white man stands atop a table in the center of a room, holding a child by the wrist in one hand and a gavel in the other. Other well-dressed white men stand nearby, smiling faintly. On the left side of the picture, one man raises a whip, about to strike a kneeling Black woman; this whip cuts through the air in a jagged line, evoking the outline of a man’s profile.6 Nearby, another man seems to brandish a riding crop. Groups of men, women, and children of African descent are dispersed around the room. While some kneel in supplication, their poses echoing the abolitionist emblems “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” and “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?,” others sit on a bench or stand against a wall, their arms in chains and shackles.7 In the left foreground, a woman kneels on the floor, embracing a child. Some figures comfort one another or plead with the white men standing over them; others entreat the heavens, heads upraised and hands clasped. On one wall, a sign labels the scene: SLAVE SALE.

But if we look closely at the page, we can see something else. The illustration in this particular book has been defaced: a jagged hole has been punched through the head of the auctioneer, tearing out his face; it has been done with such force that the rip continues in a curve that cuts him at the elbow (fig. 2b). Zooming in on the digital scan shows that the paper has been punched completely through, revealing the text of the following page and a slight tear emanating outward, suggesting the vehemence of the gesture. The other figures in the illustration have been untouched, except for a man with a raised whip who threatens a kneeling woman at the left margin of the image (fig. 2a). His face has also been excised, possibly with the point of a pencil, given the precise punch. The page is largely left intact; the image is still legible.

On this page and in this scanned file, we find concrete evidence of a reader/viewer’s response: an indexical record of an embodied reaction on the pages of a book. As much as art historians, humanists, and historians of the book herald the power of images and words, we often struggle to find documentation of these affective responses. As Leah Price remarks, “Any reception historian will sooner or later be maddened by the low proportion of traces left in books. . . . Mental actions prove harder to track than manual gestures.”8 And yet in Emory’s edition of Bibb’s book, we find both: a physical trace of an embodied action, testifying as material evidence of a reader/viewer’s reaction to Bibb’s work. Moved to (symbolic) action, this unknown reader (whom I will refer to as the “Emory iconoclast”) exacted their own violence or retribution upon the image. Yet this attack was controlled and calculated. It did not obscure the image or the text on the verso of the page, keeping Bibb’s words and story whole—this was a precision strike on the violent figures within the image.

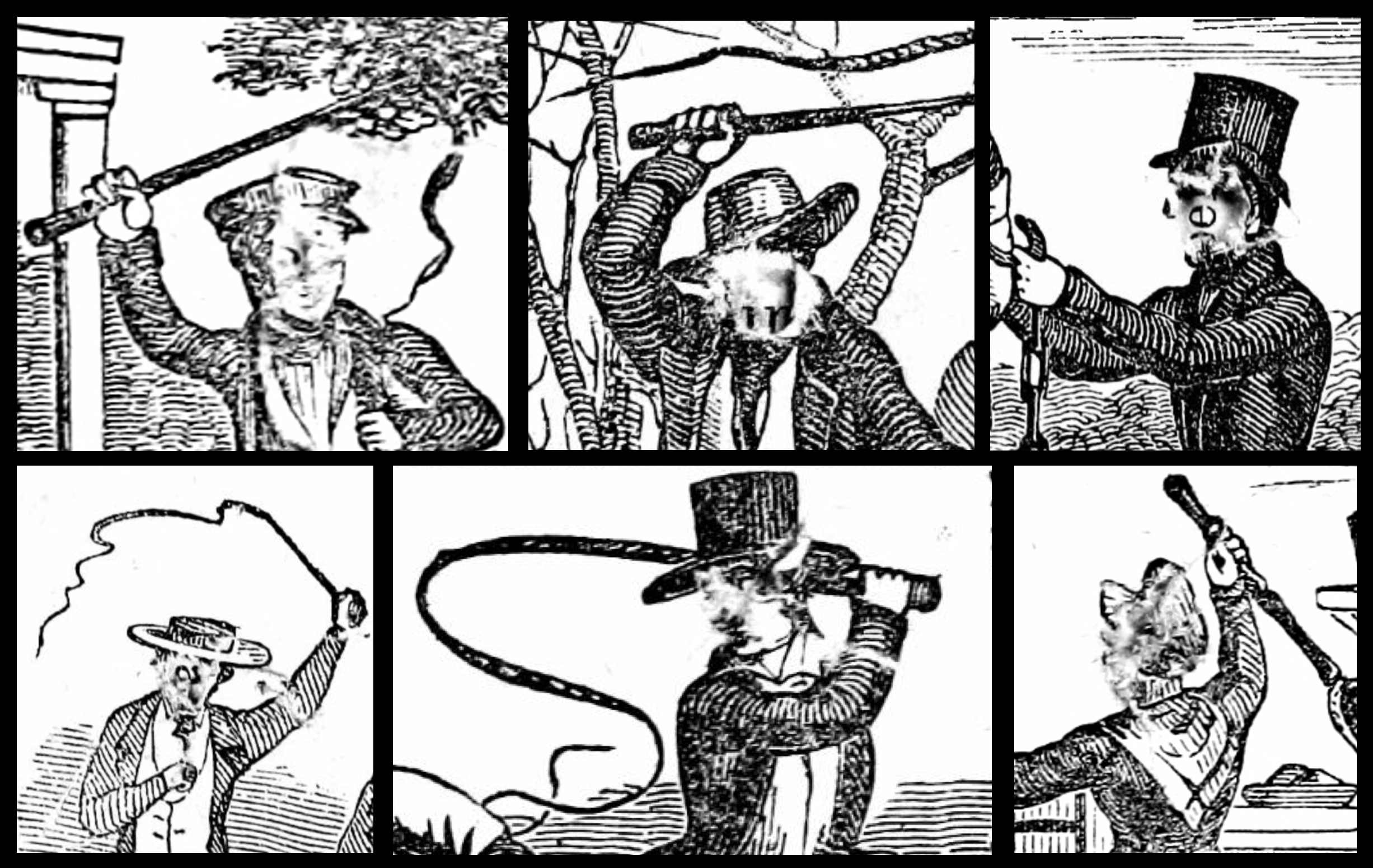

Startled out of my course planning, I clicked through to other illustrations in the book, wondering if this page was an isolated example. It was not. In every depiction of physical violence and cruelty, the heads of the perpetrators have been punched through, tearing the paper at the precise outlines of their faces. A selection of details conveys the extent of the book’s alterations without disseminating additional representations of racialized violence and torture (fig. 3). The testimony of Bibb’s text remains legible, as do the illustrations—only the features of brutalizers and torturers have been excised. Pictures that do not include white perpetrators doing active harm have been left untouched. One of the first images in the book, for example, represents a group of Black laborers, linked by chains worn around their necks and carrying tools, such as a pickaxe and shovel, over their shoulders; walking toward the left margin of the page, they look backward at a Black overseer who gesticulates but leaves his whip limp and unused on the ground (fig. 4). The men’s clothes are patched and ragged, with jagged lines and crosshatching indicating holes and gaps, paralleling the rips and tears that puncture the paper of other images that depict violence. The page itself, however, is unscathed.

There is little we can know for certain about the person or people who punctured the pages of Bibb’s book. What we do know is that the scans of the damaged book were uploaded in October of 2014.9 The volume was purchased from a rare books dealer by Emory University librarians as a standalone acquisition, not part of a lot or donation from an individual, making it nearly impossible to trace whether additional volumes from the collection had also been defaced, possibly by the same individual; the librarians have no information about the book’s provenance.10 The Emory Special Collections volume is inscribed “J. H. Stedman, 1850,” indicating its purchase shortly after publication, but the defacement could have been inflicted by a reader or readers over the ensuing 160 or so years.11 It is unlikely, however, that the damage could have occurred after the book’s acquisition by Emory Special Collections, given the number of precautions and security measures that modern rare-book libraries take with printed materials under their care.

We are left with many questions. Were these pictures defaced by an individual, or was this a communal act? Was only one plate defaced at first, with other readers later taking up sharp-tipped instruments in imitation, spurred to action? We might wonder about the tools used—whether the pages were punctured by writing instruments, like pen nibs or sharpened pencils, objects usually intended to convey textual messages or create images, or whether the tools might have been for needlework or craft, such as knitting needles or pins. We might speculate whether this intervention occurred while the institution of slavery was still the law of the land (between the book’s publication in 1849 and the abolition of slavery in 1863–65) or whether it occurred in the decades after the Civil War. This act might indeed have been a solitary, quiet expression, or it might have been part of a larger movement. The defaced book could have been shared beyond a small circle, its illustrations and their damage used as an impetus to rebellion or activism. The repeated tears in the book suggest both consistency and a kind of insistence. While it seems nearly impossible to obtain concrete answers, this defacement, in my view, powerfully evokes the agency of a historical reader/viewer and offers material evidence of a strong reaction to pictures and the written word.

What Kind of Iconoclasm Is This?

In his analysis of suffragette Mary Richardson’s stabbing of the Rokeby Venus, anthropologist Alfred Gell declares, “Art-destruction is art-making in reverse; but it has the same basic conceptual structure. Iconoclasts exercise a type of ‘artistic agency.’”12 The words and work of artist Dario Robleto helpfully reframe these tensions between creation and destruction. In conversations about his practice, with its frequent sampling, fragmentation, and incorporation of objects of historical significance, Robleto emphasizes that creative acts of alteration can also be constructive, not only destructive, processes.13 We might then imagine the Emory iconoclast’s defacement as a constructive act, one that alters the image and makes it even more meaningful by dint of this indictment of violence and oppression. Beyond the art-historical context of iconoclasm, we might also consider this part of the generative history of the book and of material texts, reframing the Emory iconoclast as a kind of “uninvited collaborator,” per H. J. Jackson.14

It is the materiality of paper and the physical qualities of the book, after all, that made the alteration of Emory’s Narrative possible.15 The tears in Bibb’s book are examples of a quiet kind of iconoclasm, carried out perhaps surreptitiously in the corner of a room. The form of the book ensures a certain degree of intimacy not afforded by oil paintings or life-size sculpture; with its small scale, this book can be held in one’s hands or on one’s lap. While the tensile strength of paper varies, it does not require brawny muscular exertion to puncture a page; indeed, the small scale of the wood engravings required precise aim and the execution of controlled and minute gestures. The perforation might even have been accomplished by calculated stillness, holding a sharp instrument immobile over the depicted face of the intended victim while lifting the page as if to turn it with the other hand. Depending on its execution, this act of defacement would barely make a sound and could be muffled by a strategically timed cough or a crackling fire.

Significantly, the damage in Bibb’s book is inflicted almost entirely upon the faces and heads of the offending figures. Many analyses of iconoclasm note a continued focus upon the eyes and face, a literal “defacement (or the mutilation of the affective parts of the face, such as the eyes and nose) often substituted for decapitation,” as Finbarr Barry Flood has described it. These assaults on images thereby parallel physical altercations; as Flood notes, “Visiting vengeance or shame on the image as if on the body of a living person, iconoclasts engage with the image as if it were animate.”16 In one of T. W. Strong’s illustrations for Bibb’s book, a white man brandishes a whip over the kneeling figure of Bibb, whose wife and child embrace him. In Emory’s edition, not only has the enslaver’s face been excised, but his elbow has been punctured as well, as if to stop the whipping or to disempower him (figs. 5, 6). Could this be a rehearsal for intervening in a scene of physical violence, holding back the arm that wields a whip?

Fig. 6. Alteration by Emory iconoclast of wood engraving by T. W. Strong, from Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave (New York, 1849: Published by the author), 148. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library, Emory University. Scan by Emory University Digital Library Publications Program; screenshot by the author from archive.org (detail)

The defacement within the pages of Bibb’s book also evokes evidence of reader response found in medieval manuscripts, wherein worshippers kissed an image of Christ or attacked representations of “evildoers,” devils, or monsters.17 In her analysis of a defaced twelfth-century Latin manuscript’s representation of the Passion of Saint Margaret, Jennifer Borland argues that material evidence—signs of abrasion and “rubbing” that suggest attempts to erase figures of sinners or torturers of saints—testifies to the power of the work. As Borland explains, “The physical destruction of evildoers was literally enacted by the reader/viewer,” noting, “perhaps the greatest power of this book lay not in its inherent value, but rather in the opportunity it provided for the physical and immediate eradication of evil” or in its fulfillment of the reader’s “desire . . . to be morally aligned with the saint.”18 Indeed, the extent of the damage, Borland argues, indicates that “the perpetrator wanted the aggressiveness of these changes to be clearly evident to subsequent readers.”19 We might imagine a similar motivation at work in Emory’s Narrative, with a past reader who wished to eradicate the power of enslavers or even perhaps to liberate Bibb and his fellow men from the cruelties and violence of slavery and abuse, if only within the confines of the image.

In his work on responses to Roman portraiture, Andrew P. Gregory has distinguished between instrumental iconoclasm—an act of destruction or defacement that is motivated by a higher purpose or “greater goal,” such as the abolition of slavery or the end of a ruler’s reign—and “expressive iconoclasm, in which the desire to express one’s beliefs or give vent to one’s feelings is achieved by the act itself.”20 With our limited knowledge about the context of the original act of defacement and about the person(s) who pierced these pages, it is difficult to establish these distinctions or motivations. Did this action extend beyond pictorial defacement and into material action to end slavery and advance Black liberation, or was this an emotive gesture that then seemed to absolve the actor of the need to take further action? This iconoclastic act, however, might have been the only rebellion possible within the parameters of the reader’s life. In an era of antiliteracy laws that forbade the teaching of reading or writing to enslaved people, the very act of possessing or reading Bibb’s story could have been an act of resistance. Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson note the ways in which iconoclasm can symbolically empower the disenfranchised: “The weak may punish offences of a human or extrahuman power beyond their reach through its available icons.”21 They explain, “Iconoclasm is a principled attack on specific objects aimed primarily at the objects’ referents or at their connection to the power they represent. Iconoclastic acts require not just the intent to remove or destroy objects but the intent to attack their relation to that power. . . . [It] may also be a rebuke or punishment to the human or supernatural figure represented by the icon.”22 Although the Emory iconoclast might not have been able to assist in the liberation of plantations, these small gestures can be read as an indictment of the cruelty depicted, a means of striking back at the institution of chattel and race-based slavery.

Even as I have described this as a “quiet” or less public form of iconoclasm, Bibb’s altered book resonates with protests of our own historical moment: sculptures that have been forever altered in our minds by protest-fueled revision. In the spring of 2020, Greg Ragland’s Salt Lake City sculpture of outstretched, almost cupped hands, meant to express the ideal of public service in the actions of emergency service responders, was doused with red paint, suggesting instead police forces with blood on their hands in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota.23 Several statues representing Christopher Columbus have been overlaid with red paint or beheaded, often accompanied by pointed inscriptions that clarify the iconoclasts’ motivations, such as the placard reading “STOP CELEBRATING GENOCIDE” that was placed near a defaced Columbus monument in Providence, Rhode Island.24 Other interventions have been more ephemeral, such as artists Dustin Klein and Alex Criqui’s light projections on the (since removed) Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, Virginia, which superimposed images of Harriet Tubman, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and the Black Power fist over the sculpture and pediment that had previously celebrated the Confederate general.25 These are additive acts of iconoclasm: alterations that still leave the original statue or monument visible and layer a further message or annotation of sorts to it. Unlike British protesters who recently hauled the statue of seventeenth-century slave trader Edward Colston into Bristol harbor, removing it from view,26 these additive acts do not delete the emblem of oppressive power; instead, they alter it so that we will always see it anew, with the intervention of the present interacting with the representation of the past, even if only in our mind’s eye. W. J. T. Mitchell has described even a temporary alteration as a powerful intercession:

The disfiguring, vandalizing, or humiliating of an image . . . can be just as potent as its actual destruction, since it leaves an imprint in the mind of the idolater. . . . iconoclasm is more than just the destruction of images; it is a “creative destruction,” in which a secondary image of defacement or annihilation is created at the same moment that the “target” image is attacked.27

Like the careful defacement of Bibb’s book, the legibility of the original symbol of power—and its rejection—is key.

A similar conceptual logic is at work in Sonya Clark’s Unraveling and Unraveled, in which the artist has invited museum visitors to join her in unraveling a Confederate battle flag, painstakingly dismantling its threads and segregating them into piles of red, white, and blue, thereby staging a public reckoning with the oppressive symbol (fig. 7). “The intent,” Clark has said, “is not to destroy the flag but to investigate what it means to take it apart, a metaphor for the slow and deliberate work of unraveling racial dynamics in the United States.”28 This “slow and deliberate” ritual further parallels the careful work of the iconoclast who punctured the paper fibers of Bibb’s Narrative, signaling resistance to the institution of slavery even while maintaining the legibility of Bibb’s testimony.

The Emory iconoclast has transformed the meaning of Bibb’s illustrations with this intervention, whether we interpret it as a defacement or an excision. This subtractive mediation further evokes the genre of erasure poetry, in which an author selectively redacts a found text, transforming its meaning and often revealing what has been left unsaid or suppressed. Tracy K. Smith’s “Declaration,” for example, hauntingly adapts the US Declaration of Independence, the blank swaths of her page conjuring violence, displacement, loss, and resistance.29 Moving from the page to the built environment, artists Shane Allbritton and Norman Lee of RE:site etched poet Quenton Baker’s alteration of historical documents from the Mackall-Brome plantation into the mirrored surface of a structure that evokes a slave cabin in the memorial From Absence to Presence: The Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland, confronting its viewers in three dimensions.30 These interventions speak back to their historical source materials, redacting and excising words that once oppressed to express a kind of agency.

Ethics of Viewing

Even as the production of Bibb’s book preceded Clark’s painstaking unraveling of the Confederate battle flag and the poetry of Smith and Baker by more than 160 years, the issues the book raises are all too resonant in our own historical moment, given the continued dominance of systems of white supremacy, including police violence against Black and Brown people, which has been made hypervisible with the ubiquity of cell-phone cameras. Reading Bibb’s text (and viewing the pictures within) had different stakes in 1849, when the book was first published. Yet then, as now, these scenes of violence demand we consider the ethics not only of the scenes represented but also of our own roles in viewing images of trauma and suffering, raising the long-standing question: can pictures and stories awaken empathy and action, or do they result solely in a kind of prurient voyeurism?31 Those of us leading courses about American history and culture know the challenge of teaching about the traumas of the past without reinflicting them on current students: how does one ethically teach a history of slavery or show a room of students pictures of torture and suffering? And how do we do so when we know these inequities and acts of state violence against Black individuals are not just part of the historical past but instead continue to unfold and ricochet across lives and headlines in our own historical moment?

Some activists and scholars have advocated for the importance of bearing witness, citing the power of images to effect both personal and social change. Courtney Baker, for example, analyzes “a rhetoric of black liberation premised upon the ethical beholding of the black body’s physical sensation.” In Baker’s reading, representation and witnessing both play crucial roles in the pursuit of justice as they work to “[assemble] a viewership that is moved to protest and eliminate the fatal racism endured by people of African descent in the United States.”32 In contrast to the objectifying or spectacularizing gaze, Baker advocates for “humane insight,” an intersubjective encounter “in which the onlooker’s ethics are addressed by the spectacle of others’ embodied suffering.”33

In analyzing historical images, Radiclani Clytus has emphasized the American Anti-Slavery Society’s reliance upon pictures and scopic engagement in advancing their cause and recruiting members, operating with what Clytus terms an “ocularcentric ethos” that evokes “spectatorial sympathy.”34 Similarly, Martha Cutter argues for the enhanced powers of a combination of image and text that work in tandem (as seen in illustrated slave narratives and analyzed in graphic narrative theory) to provoke a generative reader response. Pictures and words together, she asserts, can yield “a more radical experiential paradigm . . . [and might] move readers toward certain prosocial ends or actions more effectively than pictures or words alone,” especially when motivated by “parallel empathy” (in contradistinction to “hierarchical empathy” or pity).35 In her view, the readers’ efforts to correlate text and image are what “create intersubjectivity (shared cognition and affective states)”36 and might even “encourage a viewing reader to move beyond passive spectatorship toward active resistance to slavery’s sociopolitical regime.”37

Indeed, as one period reader of Bibb’s Narrative remarked, “This fugitive slave literature is destined to be a powerful lever. We have the most profound conviction of its potency. We see in it the easy and infallible means of abolitionizing the free States. Argument provokes argument, reason is met by sophistry. But narratives of slaves go right to the hearts of men. We defy any man to think with any patience or tolerance of slavery after reading Bibb’s narrative.”38 While Cutter’s analysis of several illustrated narratives, including Bibb’s, argues for the power of books to compel their readers/viewers to action, her primary evidence is her own formal analysis of pictures and close readings of the texts, imagining their rhetorical effectiveness and likely impact upon other users. The volume in Emory’s library offers its own material evidence of a strong reader response: an index of an emotional and intellectual reaction in its precise strikes against enslavers.

Yet these analyses are all predicated on the dissemination of images of violence inflicted upon Black individuals. With prose that hauntingly evokes video footage of Rodney King, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, George Floyd, and too many others, Baker notes this bind: “Learning from looking . . . has and continues to be a compelling project for the eradication of injustice worldwide. . . . Appeals to sentiment through the presentation of pain have been crucial to progressive black movements in America.”39 Yet the repetition of the imagery of Black pain and suffering threatens to transform these pictures and this visual evidence into what artist Parker Bright has memorably labeled a “Black Death Spectacle.”40

As Christina Sharpe notes:

We have been reminded by Hartman and many others that the repetition of the visual, discursive, state, and other quotidian and extraordinary cruel and unusual violences enacted on Black people does not lead to a cessation of violence, nor does it, across or within communities, lead primarily to sympathy or something like empathy. Such repetitions often work to solidify and make continuous the colonial project of violence. With that knowledge in mind, what kinds of ethical viewing and reading practices must we employ? . . . What might practices of Black annotation and Black redaction offer?41

Sharpe powerfully models this practice. Rather than reproducing Joseph T. Zealy’s famous and contested daguerreotypes of Delia and Drana in full, she crops and alters the photographs, showing only a small rectangle of their eyes encountering the camera/viewer. In another redaction, Sharpe reprints newspaper coverage of a young girl prosecuted, notably, for vandalism, but she overlays the printed text with black bars that conceal all lines except those that convey the girl’s own words.42

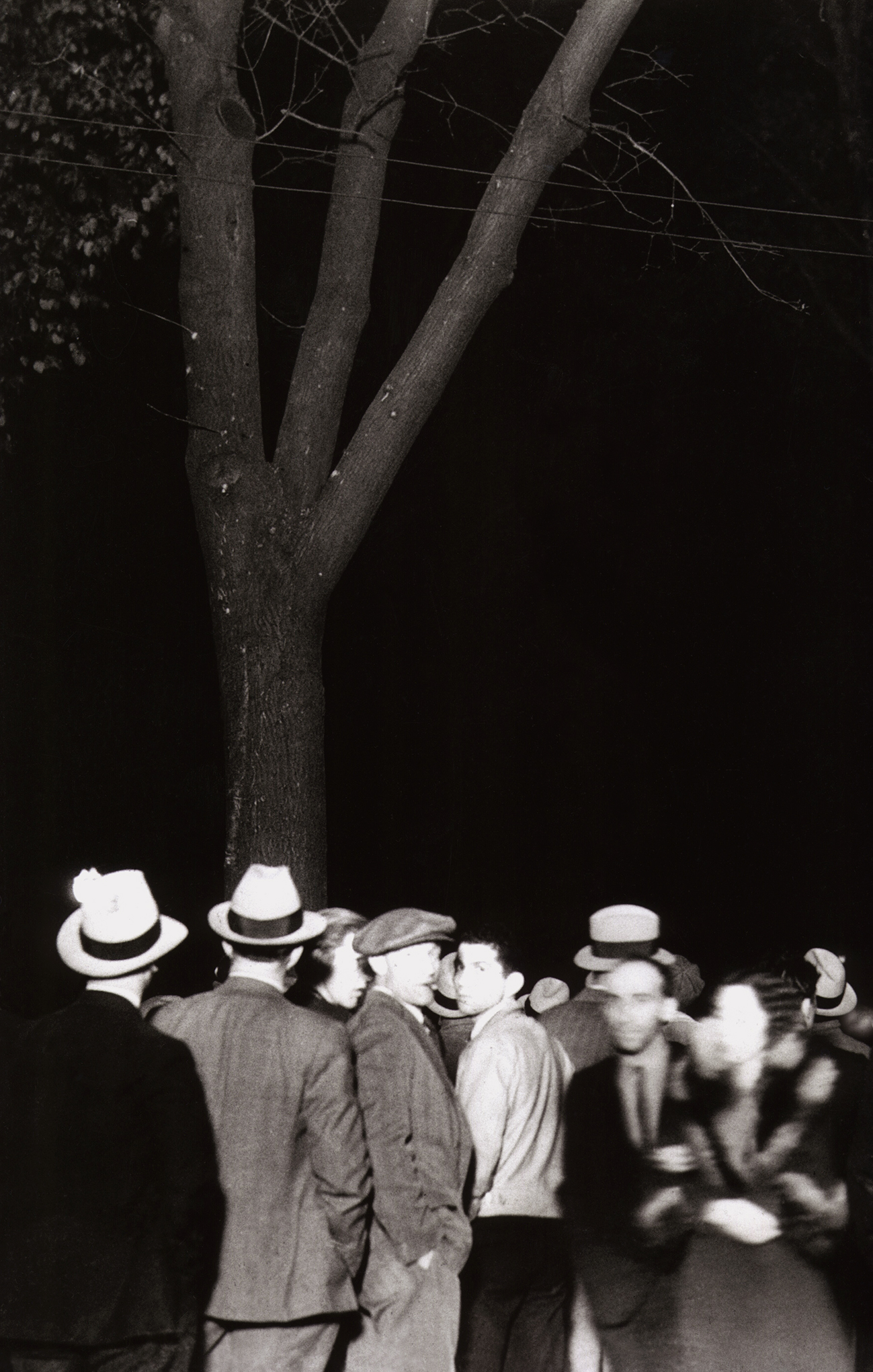

These practices parallel the Erased Lynching photographs of artist Ken Gonzales-Day (fig. 8). In these digitally manipulated versions of historical photographs, the bodies of lynching victims have been removed, leaving only the images of the perpetrators subject to our gaze.43 It is an opposite approach to that of the Emory iconoclast. Yet the redacted or defaced pictures in Bibb’s book similarly attest to a reader’s active rejection of oppression. The rips in these pictures transform them from “scenes of subjection,” as articulated and theorized by Hartman, into scenes of subversion and resistance. This intervention is what makes Emory’s edition of Bibb’s Narrative all the more powerful for teaching purposes. Beyond highlighting Bibb’s historical voice and perspective, the altered book foregrounds the agency of its reader/viewer, emphasizing the subjectivity that historical and contemporary persons bring to their encounters with media or representations of the suffering of others. This is not only a passive portrayal of the horrors of slavery but also an example of a quiet act of resistance and response, hiding in plain sight in the archive, made visible to us by digitization.

Postscript: Viewing from a Distance

I have to confess an art-historical sin of sorts. As of this writing, I have yet to see the primary object of my study in person. I have not been able to examine the materiality of its pages, the thickness of its paper, and the details of each tear and puncture. I had planned to travel to Atlanta at the end of March 2020 as part of a spring break research trip—yet the COVID-19 pandemic had other plans. For now, my research (like so many of our projects) is constrained by the parameters of what has or has not been digitized. While many libraries and archives have once again started to have staff working on site, and some are now able to scan items on request, the prevalence and circulation of viral variants and low vaccination rates in many areas mean that many of us are still dependent upon earlier digitization projects. What impact will that have on our field? As a parallel to Robert Nelson’s analysis of the dual slide projector’s influence on the discipline of art history and the kinds of arguments art historians have crafted, awareness of these infrastructural conditions or limits is crucial for the historiography of our own historical moment.44

The experience of clicking or scrolling through a digitized file yields a different kind of material engagement from turning the pages of a physical book. While the Internet Archive offers a two-page view that seems to replicate the experience of an open book, with facing pages and an illusory page-turning animation, the inclusion of the book’s cover, front matter, and copyright notices reorders the book pages so that images of what once were the recto/verso of a page are seen instead side by side (fig. 9). Even as the digitized version looks like a “book,” the file fundamentally alters how the reader would have experienced the pages in physical form and enables the viewer to see both sides of the defacement simultaneously. Moreover, readers’ interactions with the scanned file are contingent not only upon the resolution and color-selection choices made by the scanner (dpi, error diffusion, 8-bit, and the like) but also upon their own monitor settings, such as the brightness or contrast of the image. These technological considerations likely further affect and alter our perceptions and interpretations of pictures and objects.

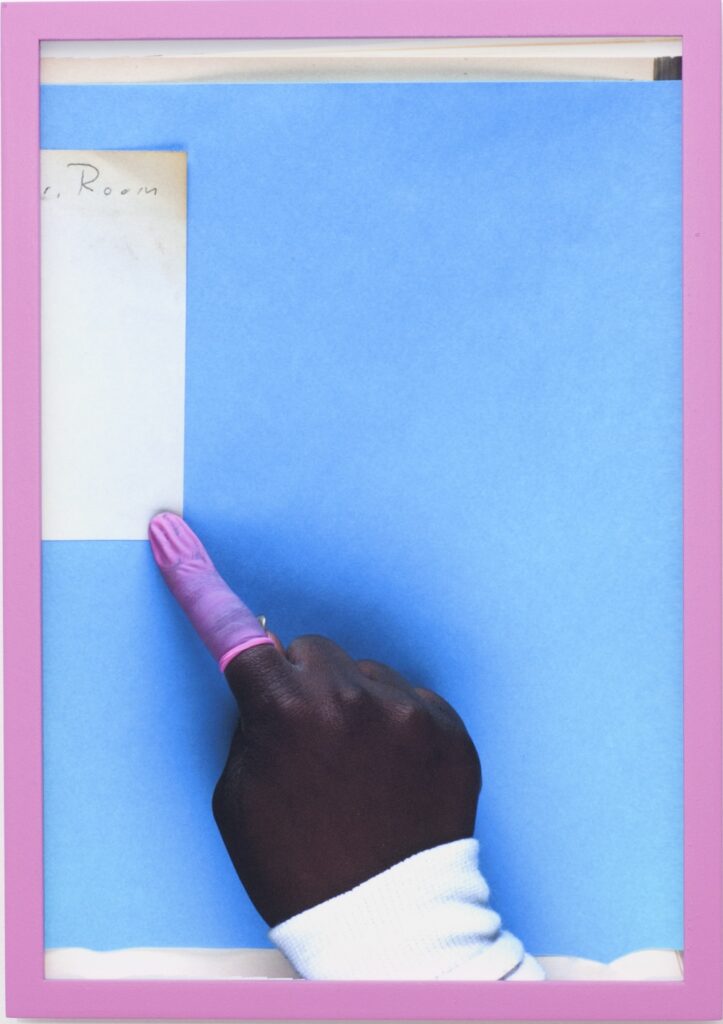

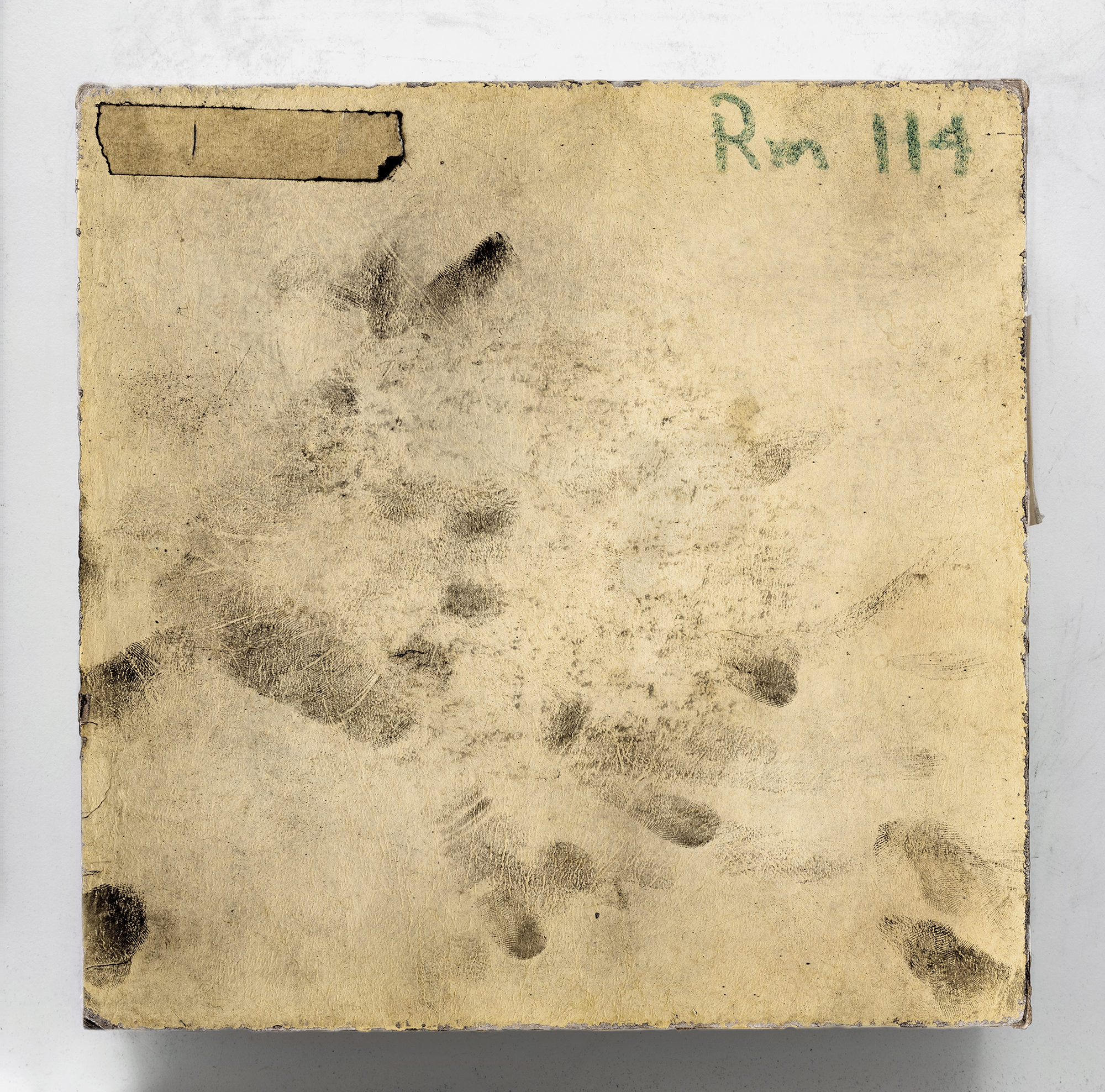

We might also analyze not only the phenomenology of reading/viewing as it was experienced in the material conditions of the original or “analogue” works under consideration but also the means by which digital scholarship is produced. As much as I have considered the hands that held Bibb’s book and punctured its pages, I must also consider how digital images of the book in its Atlanta library made it to my computer screen in Vermont. Infrastructures of online research and reliance upon the laboring bodies of scanners are brought to the fore in projects by contemporary artists Benjamin Shaykin (Special Collection, 2013) and Andrew Norman Wilson (ScanOps, fig. 10).45 These works feature the “glitches” of scanning projects: images that capture the fingers of the laborers doing the manual act of scanning or page-turning, the jumbled pixels of corrupted files, and the distorted lines of pages scanned midturn.46 Glimpses of flesh, nail polish, and jewelry evoke the largely female and BIPOC demographics of the scanners. These are the laborers who have made our research possible in this cultural moment, and Wilson’s discussion of the status of ScanOps teams should indeed raise concerns about employer-employee relations and the conditions of their labor, alongside questions about the logistics of the “digital,” the hands that photograph the books, and the server farms that transmit this “data” to us.47 Shaykin’s and Wilson’s projects emphasize the physical and phenomenological qualities of both books and the digital realms that connect us even through lockdowns and the mediations of screen technologies.

Touch, contact, and screen technologies are further foregrounded in artist Susan Dobson’s photographs of the artifacts of slide libraries in her multiple series Slide Lectures (2018): file cabinets, drawers of slides with cardboard dividers, aerial views of half-filled slide carousels.48 In one series, Dobson uses forensic techniques to dust the slide-carousel boxes for fingerprints, capturing the indexical trace of those who once carted these to lecture rooms and projection booths, registering their fleeting points of contact (fig. 11). This work has taken on new resonance for me in the era of COVID-19, when we fear the remainder of what might have been left by others’ hands or breath: a heightened preoccupation with potential traces of viruses, bodily fluids, or germs on so-called high-touch surfaces. The lasting effects of COVID-19 on our scholarly labor and perspectives on images and objects must be noted not only for our own sanity but also for historiographers of the future. As we continue to engage with the sources available to us, it is worthwhile to consider what is legible and what is not legible in the works we encounter, namely the stories that might be beyond our perception. While the tears in Bibb’s book attest to the haptic gestures of a previous reader, there must be many other affective responses, with and without material traces, that are beyond our ken. Whether in “digital” archives or brick-and-mortar ones, we should remain curious about the agency and experiences of readers and researchers before us.

Cite this article: Ellery E. Foutch, “Iconoclasm on Paper: Resistance in the Pages of Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, 1849,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13287.

PDF: Foutch, Iconoclasm on Paper

Notes

Many friends and colleagues have helped me think through the issues raised by this defaced book in conversations and exchanges over the past few years; some even read previous drafts and shared their insights and suggestions. I am especially grateful to Susan Burch, Tom Denenberg, Michael Leja, Sara Levavy, Juliet Sperling, Reed Gochberg, Sarah Rogers, Michael Newbury, Benjamin C. Tilghman, Paul Erickson, Christina Michelon, Arthur DiFuria, Jonathan Frederick Walz, Rebecca Uchill, Wendy Bellion, Jonathan Senchyne, Colin C. Boyd, and my most loyal reader, Linda B. Foutch. Thanks also to the Panorama editorial team for their suggestions, comments, and improvements, especially to Emily Burns, Kate Crawford, Erin Pauwels, and Jessica Skwire Routhier. Much of the reading and research related to this essay occurred during a Middlebury College sabbatical of 2018-2019, although most of the text was written during the winter and spring of 2021. Portions of the research were also shared as part of the American Studies Association session “Appetite for Destruction: Iconoclasm and Creative Acts of Resistance” and the Association of Historians of American Art roundtable “Iconoclasm in North America” (both originally scheduled for fall 2020 and postponed until October 2021 due to COVID-19). Kathleen Shoemaker, Courtney Chartier, and Randall Burkett of Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library were immensely helpful in answering questions via email; Middlebury’s Interlibrary Loan department and Rachel Manning in particular have made much of my research possible. I am also grateful to many people whose names I do not and cannot know, including librarians, digitizers and scanners, those who maintain our online infrastructures, and especially protestors for social justice, past and present.

- Ellery E. Foutch will be joining Panorama‘s Advisory Council in August 2022. ↵

- See Wendy Bellion, Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019); Jennifer Van Horn, “‘The Dark Iconoclast’: African Americans’ Artistic Resistance in the Civil War South,” Art Bulletin 99, no. 4 (2017): 133–67; Lauren Lessing, Nina Roth-Wells, and Terri Sabatos, “Body Politics: Copley’s Portraits as Political Effigies During the American Revolution,” in Beyond the Face: New Perspectives on Portraiture, ed. Wendy Wick Reaves (Washington, DC: National Portrait Gallery, 2018), 27–43; Sarah Beetham, “Sculpting the Citizen Soldier: Reproduction and National Memory, 1865–1917,” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2014); Sarah Beetham, “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter,’” Public Art Dialogue 6, no. 1 (2016): 9–33. ↵

- Henry Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave (New York, 1849), https://archive.org/details/26342933.4803.emory.edu/page/n5/mode/2up. ↵

- Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). On the reuse of illustrations from other antislavery publications, see Marcus Wood, “Seeing Is Believing, or Finding ‘Truth’ in Slave Narrative: The Narrative of Henry Bibb as Perfect Misrepresentation,” Slavery and Abolition 18, no. 3 (1997): 174–211; Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780–1865 (New York: Routledge, 2000), 118–34; see also Martha Cutter, The Illustrated Slave: Empathy, Graphic Narrative, and the Visual Culture of the Transatlantic Abolition Movement, 1800–1852 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017); Teresa Goddu, Selling Antislavery: Abolition and Mass Media in Antebellum America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020). ↵

- See Maurie D. McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 43–54. ↵

- The prominence of the whip recalls Elaine Scarry’s analysis of “the image of the weapon” and “the conflation of pain with power” as a means of understanding the pain inflicted upon or experienced by others: The Body in Pain (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 16–18, 27–8, 172–76. ↵

- See, for example, Jean Fagan Yellin, Women and Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989); Mary Guyatt, “The Wedgewood Slave Medallion: Values in Eighteenth-century Design,” Journal of Design History 13, no. 2 (2000): 93–105. ↵

- Leah Price, How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 19. The ongoing Book Traces Initiative tracks and indexes physical evidence of past readers. See Kristin Jensen et al., “Book Traces @ UVA,” whitepaper (University of Virginia, 2017), https://doi.org/10.18130/V3DJ42, http://booktraces.org, and https://booktraces.library.virginia.edu; Andrew M. Stauffer, Book Traces: Nineteenth-Century Readers and the Future of the Library (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). See also David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989). ↵

- See the metadata included with the book’s entry at https://archive.org/details/26342933.4803.emory.edu, which indicates an upload date of October 12, 2014. ↵

- Randall Burkett, personal correspondence with the author, August 24, 2016; ; personal correspondence with Courtney Chartier, May 25, 2021. ↵

- Although I have searched 1850 census records for a J. H. Stedman, without knowing the geographic region of residence, it is almost impossible to ascertain accurate information related to this particular individual. Michael Camille has addressed the difficulty of dating defacement with certainty: “Obscenity Under Erasure: Censorship in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts,” in Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages, ed. Jan M. Ziolkowski (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 147. ↵

- Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 64. ↵

- Dario Robleto, conversation with the author, January 29, 2018. See also Gill Partington and Adam Smith, eds., Book Destruction from the Medieval to the Contemporary (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014). ↵

- H. J. Jackson, “Marginal Frivolities: Readers’ Notes as Evidence for the History of Reading,” in Owners, Annotators and the Signs of Reading, ed. Robin Myers, Michael Harris, and Giles Mandelbrote (New Castle: Oak Knoll Press, 2005), 143. See also Peter Stallybrass and Margreta de Grazia, “The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text,” Shakespeare Quarterly 44, no. 3 (Autumn 1993): 255–83; Jonathan Senchyne, The Intimacy of Paper in Early and Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020); and Jonathan Senchyne, “Vibrant Material Textuality: New Materialism, Book History, and the Archive in Paper,” Studies in Romanticism 57 (Spring 2018): 67–85. On additive marks, see H. J. Jackson, Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001); Robert Darnton, “Toward a History of Reading,” Wilson Quarterly 13, no. 4 (Autumn 1989): 86–102; William Howard Sherman, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009); Jennifer Andersen and Elizabeth Sauer, eds., Books and Readers in Early Modern England: Material Studies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002). ↵

- The printed book’s status as a multiple, one of many copies, is also important; see Dario Gamboni, “Iconoclasm and Multiplication,” in The Destruction of Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 117–26. ↵

- Finbarr Barry Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” Art Bulletin 84, no. 4 (December 2002): 644, 648. See also C. Pamela Graves, “From an Archaeology of Iconoclasm to an Anthropology of the Body,” Current Anthropology 49, no. 1 (February 2008): 35–60. ↵

- Camille, “Obscenity Under Erasure”; Kathryn M. Rudy, “Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts through the Physical Rituals They Reveal,” Electronic British Library Journal (2011): 21; Jennifer Borland, “Unruly Reading: The Consuming Role of Touch in the Experience of a Medieval Manuscript,” in Scraped, Stroked, and Bound: Materially Engaged Readings of Medieval Manuscripts, ed. Jonathan Wilcox (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), 97–114; Beatrice Radden Keefe, “Surveying Damage in the Walters Rose (W.143),” Journal of the Walters Art Museum 68/69 (2010/11): 97–106. ↵

- Borland, “Unruly Reading,” 97, 98, 111. ↵

- Borland, “Unruly Reading,” 105. ↵

- Andrew P. Gregory, “‘Powerful Image’: Responses to Portraits and the Political Uses of Images in Rome,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 7 (1994): 89. ↵

- Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson, “Introduction: ‘O for a muse of fire . . . ,’” in Negating the Image: Case Studies in Iconoclasm, ed. Anne McClanan and Jeff Johnson (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), 4. ↵

- McClanan and Johnson, “Introduction,” 3–4 (emphasis added). On South African iconoclasm and “attacks” on authority, see John Peffer, “Censorship and Iconoclasm: Unsettling Monuments,” RES 48 (Autumn 2005): 50. ↵

- Greg Ragland, Serve and Protect, 2013, https://gregragland.com/portfolio/serve-and-protect-2013; Sean P. Means, “4 Artworks Commissioned for Salt Lake’s Public Safety Center,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 17, 2012, https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=54500732&itype=CMSID; Taylor Stevens, “After Demonstrations in Downtown Salt Lake City, a Determined Cause Still Smolders,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 31, 2020, https://www.sltrib.com/news/2020/05/31/day-after-an-eerie-calm. ↵

- Matt Zarrell, “Statues of Christopher Columbus Vandalized in Multiple States amid Controversy over the Holiday,” ABC News, October 14, 2019, https://abcnews.go.com/US/statues-christopher-columbus-vandalized-multiple-states-amid-controversy/story?id=66269347. ↵

- Jessica Stewart, “Powerful BLM Video Projections Help Reclaim Controversial Robert E. Lee Monument” (interview), My Modern Met, July 28, 2020, https://mymodernmet.com/light-projections-robert-e-lee-memorial. See also Dustin Klein and Alex Criqui, “Reclaiming the Monument,” Reclaiming the Monument: Recontextualizing Historic Spaces with Technology, https://www.reclaimingthemonument.com. ↵

- “Edward Colston statue: Protestors tear down slave trader monument,” BBC News, June 8, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-52954305; Frank Langfitt, “The Protests Heard ‘Round the World,” NPR Code Switch September 16, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/09/15/913353564/the-protests-heard-round-the-world. ↵

- W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 18. ↵

- See Rachel Rogol, “Unraveling with Sonya Clark ’89,” Amherst News, March 21, 2018, https://www.amherst.edu/news/news_releases/2018/3-2018/unraveling-with-sonya-clark. ↵

- Tracy K. Smith, Wade in the Water: Poems (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2019). The poem can also be read at the Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/147468/declaration-5b5a286052461. ↵

- “From Absence to Presence,” St. Mary’s College of Maryland, https://www.smcm.edu/commemorative. On Baker’s poetry, see “About the Commemorative/ Revealing the Power of Erasure Poetry,” St. Mary’s College of Maryland, accessed May 28, 2022, https://www.smcm.edu/honoring-enslaved/about-commemorative/#poetry; and the 2018–19 exhibition Ballast at the Frye Art Museum, https://fryemuseum.org/exhibition/6864. ↵

- See Hartman, Scenes of Subjection; Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003); Elizabeth Alexander, “‘Can You Be Black and Look at This?’: Reading the Rodney King Video(s),” Public Culture 7, no. 1 (Fall 1994): 77–94; Anne Strachan Cross, “‘The Time Has Now Gone by When Things of This Nature Are to Be Hidden from the Public’: Mediating Bodily and Archival Violence,” Panorama 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://journalpanorama.org/article/the-time-has-now-gone-by. ↵

- Courtney R. Baker, Humane Insight: Looking at Images of African American Suffering and Death (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 5, 6 (emphasis added). ↵

- Baker, Humane Insight, 5. ↵

- Radiclani Clytus,”’Keep It Before the People’: The Pictorialization of American Abolitionism,” in Early African American Print Culture, ed. Lara Langer Cohen and Jordan Alexander Stein (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 292, 294. ↵

- Cutter, The Illustrated Slave, xiv. ↵

- Cutter, The Illustrated Slave, xi. ↵

- Cutter, The Illustrated Slave, 11. ↵

- “Life of Henry Bibb,” Anti-Slavery Bugle, November 3, 1849, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1849-11-03/ed-1/seq-1. ↵

- Baker, Humane Insight, 2, 5. ↵

- Parker Bright wore a t-shirt with these words emblazoned on it as part of a protest of Dana Schutz’s Open Casket at the Whitney Biennial of 2017; see Antwaun Sargent, “Unpacking the Firestorm around the Whitney Biennial’s Death Spectacle,” Artsy, March 22, 2017, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-unpacking-firestorm-whitney-biennials-black-death-spectacle. ↵

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 116–17. ↵

- Sharpe, In the Wake, 119, 123. ↵

- Ken Gonzales-Day, Lynching in the West, 1850–1935 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006). See also Ken Gonzales-Day, Erased Lynchings, https://kengonzalesday.com/projects/erased-lynchings. ↵

- Robert S. Nelson, “The Slide Lecture, or the Work of Art ‘History’ in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Critical Inquiry 26, no. 3 (2000): 414–34. ↵

- Benjamin Shaykin, Special Collection, 2009–13, https://benjaminshaykin.com/Special-Collection; Andrew Norman Wilson, ScanOps, 2012–ongoing, http://www.andrewnormanwilson.com/ScanOps.html. ↵

- See also Kenneth Goldsmith, “The Artful Accidents of Google Books,” New Yorker, December 4, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-artful-accidents-of-google-books; Krissy Wilson, “The Art of Google Books,” https://theartofgooglebooks.tumblr.com; Leah Henrickson, “The Darker Side of Digitization,” March 20, 2014, https://bhilluminated.wordpress.com/2014/03/20/google-book-scanners. ↵

- Andrew Norman Wilson, “The Artist Leaving the Googleplex,” e-flux 74 (June 2016): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/74/59791/the-artist-leaving-the-googleplex. My interpretation is also informed by Lisa Parks, “‘Stuff You Can Kick’: Toward a Theory of Media Infrastructures,” Between Humanities and the Digital, ed. David Theo Goldberg and Patrik Svensson (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015), 355–73. ↵

- Susan Dobson, “Slide Lectures,” https://susandobson.com/portfolio/portfolio-lecture-series. ↵

About the Author(s): Ellery E. Foutch is an Assistant Professor of American Studies at Middlebury College.