“If You Can Read This . . .”: Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream and the Viewing of His Pictures

In June 2014, a collector and amateur art historian emailed me about the inscription in the lower left-hand corner of the Winslow Homer (1836–1910) painting The Gulf Stream (fig. 1), just below the signature and date. This is a painting with which I had limited experience and, I must confess, for which I had limited affection. In spite of the inspired advocacy of such writers as Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. and Peter H. Wood, the earlier, chiding writings by Barbara Novak and Roger Stein were what had always resonated with me, as when Stein simply condemned it as “poorly painted, harsh in color, melodramatically overstated and terribly derivative in both its symbolism and its structure.”1 So, in order to respond to the email, I had to look at the picture more intensely, more openly, than ever before. My correspondent did not convince me about his interpretation of what the artist had written on this canvas or why he had done so. In the process of looking, however, I perceived a reading of the inscription—in what has proven to be an ironically close examination both in person and via Google photographs—fuller than has yet appeared in the most authoritative publications on the work.2 Since this inscription affirms an important but rarely heeded point concerning viewing distances, and since it might assist in a more apt appreciation of many late-nineteenth-century paintings, it seems worth sharing.

I say “many . . . paintings,” for as various as were their techniques, their styles, and their careers, on at least one thing Homer, James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) could all agree: they intended their pictures to be seen from specific distances, most often farther away than most people tended to stand. They made this clear by both word and deed. Whistler, for example, wrote of Nocturne: Blue and Silver—Bognor (1872; Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC): “Go and see if ever you saw the sea painted like that! And the mystery of the whole thing—nothing apparently when you look at the canvas, but stand off—and I say the wet sands and the water falling on the beach in the blue glimmering of the moon—and the sheen of the whole thing—enfin—then I have exhausted my subject.”3 At the very beginning of his drawing manual, Eakins declared that “a picture can be correctly looked at from one point only, and the spectator should have a care to place himself at that point.”4 Numerous witnesses wrote of how Sargent, while painting, would dash away from his easel to observe his picture’s effect from a distance, then scoot forward, “with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only with equal suddenness to repeat the wag-tail action,” metaphorically equating the painter with a small bird known for its swift darting motions and documenting for us the fact that, to see his own work, Sargent established considerable space between himself and the canvas.5 Critics of the day, too, understood that artists wanted their viewers to stand a certain distance from their pictures. A writer in 1908 went so far as to wish that Sargent would annotate his works to let people know “at how many feet or yards distant the precise effect was to be found.”6

Well, one artist had already done precisely that.

Homer was among the most adamant of painters on this point. Telling testimony to this is the environment that the dealer Reichard & Co. constructed, presumably with the artist’s input, when Homer’s four major paintings of 1890—including his first two large-scale Prouts Neck seascapes—made their debut in New York; viewers were apparently kept physically from approaching too closely to Winter Coast (1890; Philadelphia Museum of Art) and Sunlight on the Coast (1890; Toledo Museum of Art). The writer for the New York Times reported:

The range at which these pictures look their best is very great; at a distance of thrice the width of the canvas their beauty is far from what it is when the observer stands ten picture breadths away. To insure this respectful distance the two last named paintings [i.e., the two marines] are roped off, so that one must examine them from the other side of the gallery.7

For this observer, the paintings looked better at forty feet than they did at twelve feet away (and how many viewers today stand even that far back?).

Others of the time who wrote about Homer’s works expressed similar thoughts. Complaining of a “lack of refinement in the treatment of the details” in A Light on the Sea (1897; National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection), the Evening Post critic, as just one example, excused this shortcoming by noting that, “at a distance from which these things are not noticeable the picture masses with unaffected and powerful simplicity. The figure and the shore, dark against the moonlit sea, merge into a single confirmation that is singularly impressive.”8 Painter Kenyon Cox affirmed that Homer’s works in general “can hardly have too much light or too much distance.”9 If someone was to call Homer’s seascapes, as one critic opined of the two 1890 marines, “true in effect, but a little painty,”10 Homer’s and Cox’s responses would likely have been words to the effect of, “Friend, just step back another few feet.”

Homer himself often noted the need to find an appropriate viewing distance for his late works. Of Cannon Rock (1895; The Metropolitan Museum of Art) he wrote:

It was painted in 1895 & has been hanging in my studio untouched. I did not put it out or change it in any way as the breaking on the bar part of it looked so broken & so like decanters & crockery, & at the same time looked so fine at a proper distance. I now take the chance of sending it out.11

Here we can imagine him stepping back and forth in the studio, moving closer or farther away as he finds the “proper distance” from which to see the work.

The same held true of Early Morning after a Storm (1902; Cleveland Museum of Art). When, after exhibition in Chicago and New York, the painting remained unsold, he reworked it. Back once more in New York, it still garnered negative responses from the critics, one writing of it as “a heaving sea of chalk and pink, with waves topped by bunches of wool, and the distant stretches of his ocean are illuminated milk.”12 Homer blamed at least some of this negative critical response on the close viewing distance forced on the work by its hanging at the Society of American Artists: “They hung it in a little room at the Academy. Why, of course it would look brutal there.”13 At least one critic agreed with this reasoning: “Here was a picture to humor by hanging it high in the Vanderbilt Gallery, in order to give it the benefit of distance, or at one end of the South—more’s the pity! It would have been kinder to reject it than to place it where it looks so ill.”14 Homer had it again sent to Prouts Neck to “overlook” it.15 Putting it once more before the public, this time in Pittsburgh, he wrote, “I know that it will now be understood & if it can be hung in the long gallery on the second line & at the distance across the gallery it will be admired.”16

In his correspondence to dealers and exhibition organizers he could be insistent and specific concerning viewing distances. In 1907, for example, he wrote to a dealer who was going to sell his much earlier Shepherdess of Houghton Farm (1879; Private collection): “If you will place some article of furniture in front of this in your Gallery or hang it up high to keep people from smelling of it—and at their proper distance—three times its width I should say that would be a good hint to them & something they should know.”17 This echoes his earlier note, of 1904, to the managers of Knoedler Galleries concerning Kissing the Moon (1904; Addison Gallery of American Art) and Cape Saguenay (1904; Private collection): “Your window is the only place where a picture can be seen in a proper manner—That is at a point of view from which an artist paints his Picture—to look at and not smell of.”18 On occasion, it is tempting to think that he is being hyperbolic, as when in 1907 he wrote of Early Evening (1885/1907; Freer Gallery of Art): “It can be seen properly from the opposite side of 5th ave the old Stewart building corner.” He continued, however, to specify in a way that clarifies his sincerity on the point: “—as it is painted at the distance of 60 feet from the artist. That is the rule for the nearest figure on the base of a picture.” With typical, albeit acerbic, wit he added a drawing at the bottom of this note, showing a man with his nose against the painting, captioned: “This man cannot see it.”19

Homer was not joking about the virtues of seeing his works from a distance. While he did not necessarily dance about in the act of painting, as Sargent did, when it came time for him to examine one of his works, he practiced what he preached (and more): “Why, I hang my pictures on the upper balcony of the studio, and go down by the sea seventy-five feet away, and look at them. I can see the least little thing that is out. I can then correct it.”20

Much of this is recognized and has been repeated in the literature for more than half a century. Even today, however, very few institutions take care to create sympathetic installations that encourage viewers to put a sufficient distance between themselves and Homer’s works, even though understanding of the works benefits from such distance. For when one steps back from any of the late marines three or more picture widths (generally twelve or more feet), the picture’s character changes dramatically: deep space opens out, foreground details diminish in import, and colors shift in their relationship to one another. Most often these shifting perceptions settle a palpable sense of atmosphere over the whole.21 This evocative illusionism is clearly what Homer’s contemporaries prized in his works: “They will always be windows opened in a wall rather than squares of brocade stretched upon it; they have none of the amenities of the drawing room, and you might almost as well let the sea itself into your house as one of Homer’s transcripts of it.”22

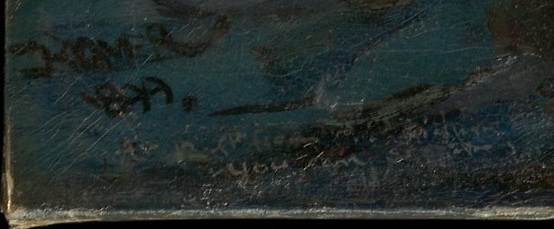

Homer was certainly thinking about vantage points and ways of perceiving distances with The Gulf Stream. He wrote to the director of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts when preparing to send the picture to Philadelphia for its debut in early 1900: “This first shark is 15 ft long & the boat is 30 feet away from him—into the picture. Do not smell of this, but stand off!”23 In spite of this admonitory care, however, the painting did not find a buyer in Philadelphia. Nor, for the next six years, in any of the other places Homer sent it: Pittsburgh, Venice, Chicago, and Des Moines. Only in mid-December 1906 did The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s trustees—on receiving a petition from artists—reverse their October decision declining the opportunity to purchase the painting and, using the Wolfe Fund, acquire it as the first Homer painting for the museum’s collection. We know that between 1899 and 1906, Homer had amended the painting in ways both large and small.24 Sometime before his final work on the picture, he evidently felt the need to instruct the public in how to look at it. To anyone who had the temerity to press a nose against the picture, to sniff at or try to smell it, he gave a clear message. In the lower left corner, just below his signature and the painting’s date, Homer wrote in light-colored script, as if it were flotsam from a wreck (fig. 2): “At 12 feet from this picture/you can see it.” Long before bumper stickers proclaimed, “If you can read this you are too close,” Homer set such an admonition on the face of a major painting.

Distance is necessary for the reading of deep space of Homer’s paintings—and such illusion mattered to him. Sadly for us, distance from paintings—so important to Homer and others of his contemporaries—is not a luxury that museum visitors generally allow themselves or are permitted. They thus lose a significant aspect of what the artist intended. Homer’s admonition that his audience should experience the “point of view from which an artist paints his Picture” suggests that it would be worthwhile to reinstate in our experience of the works the illusionism and atmosphere that standing back allows, balancing the emphasis on brushwork and surface, as well as the engagement with social and cultural themes, that come so naturally to our twenty-first-century sensibilities. What we gain from these latter approaches is rich and rewarding. It is augmented, however, by valuing as well the illusion that results from “standing off.”

It is worth remembering that when Homer first wrote of The Gulf Stream, before sending it to Philadelphia, he declared:

I think this is the last picture I shall ever paint for fun. This picture is called “The Gulf Stream.” Please [do] not change this title. I have some landscape figures in it—enough to give interest to it but of little account in this great subject of the “Gulf Stream.” You may remember “Turner’s Slave Ship” with the chain cables floating on the water & the impossible arms & legs that have been admired by the public. These figures of mine [are of] about the same value to the picture.25

Homer gives us a challenging bit of prose to parse. The idea of making one of the most harrowing of pictures be a source of fun signals either high irony or an extreme emotional coolness. And is he truly casting aspersion on the Turner painting, as it seems—echoing critical responses to the painting when it was seen in New York a quarter century before?26 If so, is he dismissing his own central figure as staffage? I suspect that, as he had done throughout his career, he straddled meanings and intentions, establishing a balance between options that forbids any definitive answer as to his purpose and his aim. His own polyvalence allows us to find multiple riches in the work. When we stand near to the canvas, we cannot help but focus on the sailor and the sharks. But if we step back, to a “proper distance,” other elements—the ocean, its might, its wonder—come to the fore. Movement back and forth allows the picture to work its Homeric magic on us.

Cite this article: Marc Simpson, “‘If You Can Read This . . .’: Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream and the Viewing of His Pictures,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1638.

PDF: Simpson, If You Can Read This

Notes

- Roger B. Stein, Seascape and the American Imagination (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1975), 112. See also Nicolai Cikovsky Jr., “Homer Around 1900,” Studies in the History of Art 26 (1990): 132−54; Peter H. Wood, Weathering the Storm: Inside Winslow Homer’s Gulf Stream (Athens: University of Georgia, 1904); and Barbara Novak, American Painting of the Nineteenth Century (New York: Praeger, 1969), 187. ↵

- Most notably, Natalie Spassky, American Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born between 1816 and 1845 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), 482−90; and Lloyd Goodrich, edited and expanded by Abigail Booth Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 1890 Through 1910 (New York: Goodrich-Homer Art Education Project, 2014), 285−90. The museum currently records the inscription as “{at lower left, partly painted over}: At 12 feet you can see it” (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11122, accessed November 20, 2017). Goodrich/Gerdts publishes a close variant: “{obscured} at 12 feet . . . you can see it” (5:285). ↵

- Whistler to Cyril Flower, July/August 1874; quoted in Lucy Cohen, Lady De Rothschild and Her Daughters, 1821−1931 (London: John Murray, 1935), 198. ↵

- Kathleen A. Foster, ed., A Drawing Manual by Thomas Eakins (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2005), 47. ↵

- Edmund Gosse; quoted in Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927), 74. ↵

- Laurence Housman, “Mr. Sargent’s Water-colours,” Manchester Guardian, June 3, 1908, 14. ↵

- “Four Paintings by Homer,” New York Times, January 16, 1891, 4. The review concludes: “It is not merely the tremendous ‘go’ in the shore scenes that will interest art lovers, but the superb qualities of color which Mr. Homer shows in these four paintings. We should like to know who among living European artists is capable of the big and masterly work in marines one finds here.” There were no ropes in front of the two figure-centered paintings (A Summer Night {1890; Musée d’Orsay, Paris} and The Signal of Distress {1890; Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid}). ↵

- New York Evening Post; quoted in William Howe Downes, The Life and Works of Winslow Homer (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 202. ↵

- “Art Here and Abroad—Cox Talks of Homer’s Pictures,” New York Times, January 12, 1908, X10. ↵

- Untitled paragraph, New York Herald, January 26, 1891, 5. ↵

- Homer to Knoedler and Company, December 3, 1900, Archives of American Art; quoted in Spassky, American Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 475. ↵

- “Fine Arts: Exhibition of the Society of American Artists,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 2, 1903, 14. ↵

- Homer to John Beatty, September 1903; quoted in Lloyd Goodrich, Winslow Homer (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1944), 177. ↵

- “The American Artists,” New York Times, March 29, 1903. ↵

- Which he did and wrote, when he sent it back to New York: “I have lightened the scale of the color to bring it within the range of the public. It’s the same thing. Easy to be understood.” (Homer to M. Knoedler and Company, September 14, 1903; quoted in Goodrich/Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 337). ↵

- Homer to John Beatty, September 14, 1903; quoted in Goodrich/Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 337. ↵

- Homer to William Clausen, January 22, 1907; quoted in Lloyd Goodrich, edited and expanded by Abigail Booth Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 3, 1877 to March 1881 (New York: Spanierman Gallery, 2008), 198. ↵

- Homer to Knoedler and Company, November 8, 1904; quoted in Goodrich/Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 365. ↵

- Reproduced in Lloyd Goodrich and Abigail Booth Gerdts, Winslow Homer in Monochrome, exh. cat. (New York: M. Knoedler and Company, 1986), 85. ↵

- Homer to John Beatty, September 1903; quoted in Goodrich, Winslow Homer, 177. ↵

- I assert this not solely on the basis of personal observation but on the comments of those students in the Williams College Graduate Program in the History of Art from 2000 to 2013 and again in 2015 who took my seminars and spent time in the galleries of the Clark Art Institute with me. ↵

- Samuel Isham, The History of American Painting (New York: Macmillan, 1905), 355−56. ↵

- Homer to Harrison Morris, November 26, 1899; quoted in Goodrich/Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 286. ↵

- These are well documented in Spassky, American Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 482−90; and Goodrich/Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 287. ↵

- Homer to Harrison Morris, November 26, 1899; quoted in Goodrich/Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, Volume 5, 285−86. ↵

- Elizabeth Athens, “Homer’s Odyssey,” The Magazine Antiques (November/December 2017): 108−13. ↵

About the Author(s): Marc Simpson is an independent scholar who has written extensively on Winslow Homer.