In Search of Asian-ness in America: Situating Wing Young Huie’s Photographic Road Trip

PDF: Wang, In Search of Asian-ness

Born and raised in Duluth, Minnesota, Wing Young Huie (b. 1955) is the youngest of six children and the only one of his siblings not born in Guangdong, China. When Huie visited Hong Kong, where he purchased his first camera at the age of twenty, it was bizarre and fascinating to him, because he had been exposed to very few Chinese people in his hometown. The Huies were the only Asian family in their neighborhood, and Wing was the only Asian kid in school until the tenth grade.1 Despite growing up immersed in US culture, Huie experienced the United States as an outsider because he looks Chinese.

In August 2001, Huie and his then-wife, Tara, set out on an extended road trip for nine months in their green Volkswagen Beetle. Huie has always been curious about places where Asians gather. When visiting a new city, Huie’s first impulse is usually to find the local “Chinatown.” This interest in documenting Asian American experience can be seen in his earlier project photographing the Frogtown neighborhood in Saint Paul, Minnesota.2 It can even be traced to Huie’s first published photo-essay in the magazine Lake Superior Port Cities (1979), documenting his hometown, Duluth, and featuring his father, Joe, who ran a café there for many years before retiring.3 When he began his road trip, Huie’s initial idea was to photograph Chinese restaurants throughout the United States because, as he puts it, “there are Chinese restaurants everywhere,” implying that there are Chinese people everywhere.4 Beyond this, most of Huie’s trip was largely serendipitous, with little planning in advance, except for visits to Slope County, North Dakota, one of the least diverse areas in the United States, and Hawaii, one of the most diverse. He took a counterclockwise route and made a point of reaching every border and coastal state.5

The trip ended in May 2002, and after two years of sorting through some seven thousand photographs and thirty hours of digital video footage, Nine Months in America: An Ethnocentric Tour by Wing Young Huie premiered at the Minnesota Museum of American Art with 105 photographs, a two-and-a-half hour video that played on three screens, nine “stories” written by Wing, and the journal kept by Tara during their travels. The exhibition became the basis for the book Looking for Asian America: An Ethnocentric Tour by Wing Young Huie (2007).6

Tara often jotted down notes in the passenger seat and kept a travelogue that later became the text “Views from the Road,” which was included in the exhibition and book.7 Her remarks often corroborate Wing’s experience while also offering an honest, critical, and thoughtful take from her perspective as a white woman raised in middle-class suburban Minnesota. Tara grew up with white privilege but began encountering racism as Wing’s wife and because of the focus of their trip.8 For Wing, a relationship to white normativity preceded his marriage to Tara because of the extent that he felt formed by mainstream culture, like Garrison Keillor’s radio variety show, A Prairie Home Companion, which he uses as a point of departure for discussing the complexity of his racial identity:

I was born and raised in Lake Wobegon, assuming not only that I was like everyone else but also that I looked like everyone else. After all, you don’t grow up with a mirror in front of you; you become what you see. As I spent more time away from home, mass culture became my mirror.

From time to time, though, that bubble was burst. Like when my junior high band teacher announced to my fellow band members that they should look to me as a role model because of my industrious Chinese work ethic. Or when that cute girl who worked at Bridgeman’s said she couldn’t go out with me because her dad had fought in World War II.9

Although Huie’s identity was shaped by the culture of his Chinese immigrant parents, it was overwhelmed by white American-ness over the years.10 Huie describes how he slowly realized his basic cultural filter was white, formed by Mary Tyler Moore, Paul Bunyan, and the Vikings. Yet despite the fact that Huie was fully immersed in US popular culture, his appearance suggests otherwise. While to many Minnesota is considered identical to Lake Wobegon, Huie is, however, one of hundreds of thousands of hyphenated Minnesotans who do not have a role in Keillor’s fictional creation.11 In an earlier project of documenting the Frogtown neighborhood in Saint Paul, Minnesota, especially the burgeoning Southeast Asian communities there, Huie reflected on his own family’s experience and saw himself reflected in the younger Hmongs he was photographing who were becoming “acculturated, Americanized.”12

Wing’s collaboration with Tara is reminiscent of the collaboration between Paul Schuster Taylor and Dorothea Lange for their coauthored book, An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (1939), where Lange’s photographs and recorded testimonies of migrants on the highway were accompanied by Taylor’s essays on socioeconomics. In the Huies’ case, while Wing did most of the photography, they interacted with people they met on the road as a couple. Because they worked together in this way, the collaboration between Wing and Tara provides a multiracial lens on the Asian American experience in the United States.

Huie’s photographic road trip is reminiscent of the long tradition of seeing and picturing the United States on the road, as exemplified by Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld, and Baldwin Lee.13 This article revisits Huie’s “ethnocentric tour” across America, situating his work in the genre of US road photography, focusing on the Asian-ness he encountered and documented during the trip. Huie knew the works by several of these photographers, and he even paid homage to some photographs from Frank’s The Americans. Yet Huie’s focus on how he and other Asians experienced and were represented in the United States distinguishes his project since he was specifically searching for and reflecting on the experience and representation of Asian-ness in America.14

Chinatowns and Chinese Restaurants

In Huie’s photograph Bar, Chinatown, San Francisco (fig. 1), we see Michael Jordan on the television screen juxtaposed with a Buddhist altar cabinet at a San Francisco bar. The photograph projects a sense of loneliness, especially without any sign of bartenders or customers present. In this way, it echoes one of Frank’s iconic photographs from The Americans. In Restaurant—U.S. 1 leaving Columbia, South Carolina (fig. 2), Frank focused his camera on a TV set in a roadside café along the US Highway 1. On screen is Oral Roberts, one of the most famous television evangelists in the United States. As a Jewish immigrant from Switzerland, Frank was likely interested in the phenomena of US televangelism, and he captures a sense of isolation as Roberts preaches to this empty diner that is similar to Huie’s deserted Chinatown bar.

While both Frank and Huie created restaurant images that convey a sense of loneliness, Huie’s barroom scene also reflects dimensions of his particular hyphenated Asian American experience. The religious iconography of the Buddha is a strange or exotic religious item for Huie, since he grew up Presbyterian (although his mother used to make him pray to the Buddha every New Year).15 This photograph was taken in the famous Buddha Bar in San Francisco’s Chinatown, which features Buddha-themed décor. Huie thought the Chinatown in San Francisco was the closest thing to China that he had experienced until he went to mainland China in 2010. Basketball is Huie’s lifelong passion, and he has played in a weekly organized pick-up game for thirty years. By juxtaposing Jordan playing basketball with a Buddhist icon, Huie simultaneously displays something familiar and something foreign to him—the inverse of what his Asian heritage may lead others to think. In retrospect, the TV is presumably airing coverage on ESPN about Jordan’s return to the NBA in 2001. For many NBA fans, Jordan might be considered a “god,” making the link between Frank’s and Huie’s images particularly resonant.16

Huie’s urge to photograph restaurants has a precedent in road-trip photography as well; in addition to Frank, Shore photographed numerous restaurants for two of his book projects, American Surfaces (1973) and Uncommon Places (1982), famously stating: “I started photographing everyone I met, every meal, every toilet, every bed I slept in, the streets I walked on, the towns I visited.”17 In Clovis, New Mexico, June 12, 1972 from American Surfaces (fig. 3), Shore records the food he ate in a snapshot that combines a Warholian take on mundane subjects with the message of “I was here”; the picture functions as a diary and souvenir.18 In Town and Country Restaurant, East 7th Street, Parkersburg, West Virginia, May 16, 1974 from Uncommon Places (fig. 4), Shore set his camera up high to capture empty booths with the roadway outside framed by the window, making clear the image was of a roadside restaurant. Yet unlike some of his predecessors who photographed dining establishments, Huie has a personal connection to Chinese restaurants. He started keeping the books for his father at Joe Huie’s Café when he was twelve and later cashiered, washed dishes, waited on tables, bused, and cooked at other places. His brother opened a restaurant in Duluth, the Chinese Lantern, where Huie cooked in his early twenties, and Huie’s mother encouraged him to open his own restaurant rather than pursue photography.19

During his trip, Huie conversed with the people he photographed, which sometimes led to uncomfortable conversations and sad truths about the Asian American experience. When he photographed the chef and former owner Ping at the China Lantern restaurant in New Mexico in Ping in the Kitchen, China Lantern, Carlsbad, New Mexico (fig. 5), Huie recorded Ping’s particular story and identified elements of a shared history between them. Ping revealed that he was an immigrant who had left his family behind in China and sent money back to support them. Ping first opened the China Lantern in downtown Carlsbad in the 1950s but quickly outgrew the space. Since anti-Chinese laws were still in effect, he could not buy land in town, so he began to build a new place outside of the city limits.20 Just a week before the opening, someone linked to organized crime in Carlsbad detonated a bomb in Ping’s restaurant, possibly because they did not like Ping’s success in a jurisdiction where the local mafia enforced business fees. Fortunately, the larger community was outraged by this act of terror, and the bank lent Ping the money to rebuild. With the townspeople’s support, Ping’s rebuilt his business.21 Ping’s story is part of the larger unsettling history of discrimination and violence against Asian Americans and their business properties, which also took the form of the Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871, the San Francisco riot of 1877, the massacre of Chinese American minors in Rock Springs, Wyoming in 1885, and later the Los Angeles riot of 1992 against Korean Americans and their businesses after the acquittal of the four Los Angeles police officers who used excessive force in the videotaped beating of Rodney King.22

Media Landscapes

The TV screen is often a part of travelers’ stops along their journeys, and it appears frequently in related photography. Like the windshield while travelers are on the road, the TV screen provides another window through which to see the world, whether in a restaurant or a motel room. Particularly relevant to Huie, the images one encounters on television are often crystallizations of cultural attitudes toward race.

On this trip, Huie watched The Keys of the Kingdom in a motel room, an event he recorded in Coos Bay (young girl), Oregon (fig. 6) The 1944 film, starring Gregory Peck, is an adaptation of the novel of the same title about a Catholic missionary to China. In this photograph, the movie stands in for a common theme in Huie’s experience of Chinese culture. Despite being Chinese American, China for Huie is actually a foreign land, which he experiences predominantly through a US lens. In this way, despite a formal resemblance to images like those in Friedlander’s series Little Screens, Huie’s picture comments more specifically on US media representations of Asian people and the degree to which they shape an American idea of what it means to be Chinese.

Huie took the photo Graves of Bruce and Brandon Lee, Seattle, Washington (fig. 7) during his road trip, perhaps selecting the site because Bruce Lee was one of the most famous martial artists and actors in the United States. In this picture, Huie documents an African American man in athletic clothing and a bandana posing behind the tombstones. Huie recalls that when he first heard the news about Bruce Lee’s passing, it shocked him more than the death of other celebrities. Lee was a star who had cropped up at both positive and negative moments in Huie’s life. When Huie was working at the Chinese Lantern after graduating high school, a girl he was interested in told him that Lee was her favorite movie star. Huie thought that was the most seductive thing that she could have said to him. Many years later, while Huie was playing pick-up basketball, he was called “Bruce” as an expression of racial microaggression.23 Lee, therefore, embodies two opposing attitudes white culture directed to Asian Americans in Huie’s life experience: that of both idol and stereotype.

Standing Out and Belonging

Friedlander is known for showing his idiosyncratic sense of humor in works such as Lee Ave., Butte, Montana (fig. 8), which is comparable to Huie’s Somewhere in Texas (fig. 9). While Friedlander positioned the “Lee Av.” sign close to the center of his composition, bisecting the utility wires in the background and flanked by other poles, Huie tilted his camera to give a more haphazard snapshot feel to his picture. There is a sense of rhythm, however, since the “China” street sign aligns with the utility poles in the background, reinforcing the repetition and dynamic aspect of the composition. Whereas Friedlander captured his own, relatively common given name on a sign, Huie’s choice to photograph a street named “China” evokes his search for a Chinese cultural identity rather than just a personal one. Interestingly, Huie’s composition perhaps implies the priority of a Texan American identity over a Chinese American one, since the signs in his image read “China,” “Yield,” and “Texas,” despite the fact that “China” occupies the foreground while “Texas” looms in the background.

For Huie, his road trip provided a means for him to identify an Asian America (albeit a hyphenated one), as well as to search for his own identity as a Chinese American. In Huie’s Death Valley, CA (fig. 10), an Asian girl appears to be a tourist posing in front of the iconic landscape of the American sublime. The girl in the muted blue outfit is surrounded by a vast desolate landscape in grayish earth tones, which emphasizes a sense of emptiness and isolation. It is unclear whether the girl is from Asia or if she is Asian American/Chinese American, with a family that has lived in California for generations. The photograph recalls Shore’s Grand Canyon, Arizona, June, 1972, which captures the touristic experience of seeing the United States, especially the geological wonders of the American West. While the landscape in Shore’s shot is vague, the title’s declaration that the picture was taken at the Grand Canyon is critical and symbolic. As a native of New York City, Shore considered his cross-country road trip as an automotive Grand Tour that allowed him to experience and identify with the United States while responding to the photographic tradition established by Walker Evans and Robert Frank. Where the urban-based Shore seems to have found friendship in the remote southwestern landscape, Huie chose an image of an isolated Asian person in a distinctly “American” landscape.

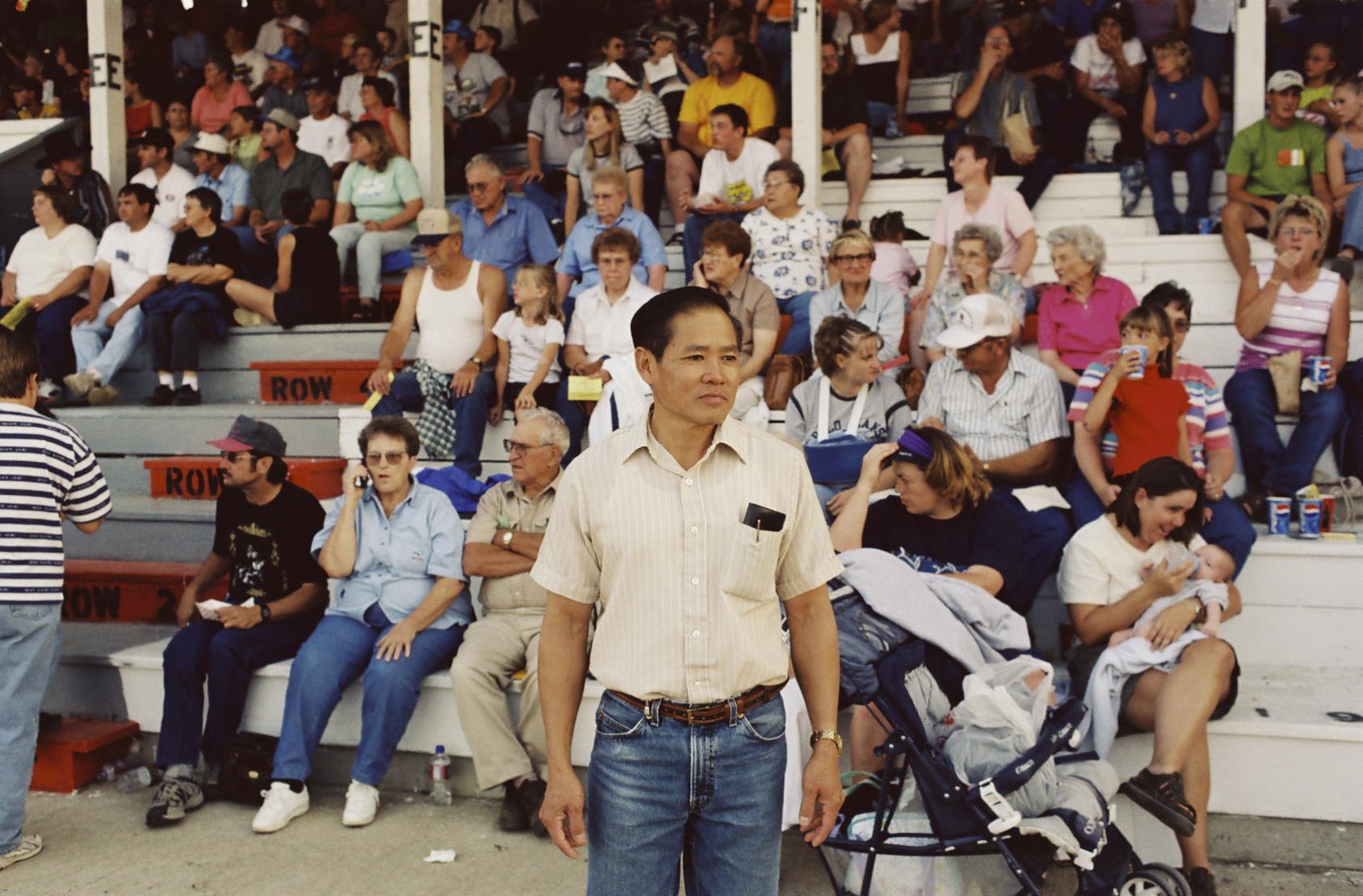

Huie had never been to either a demolition derby or to rural Montana until his cross-country road trip. Rather than capturing the sight of smashing metal at the violent vehicular spectacle, Huie turned his attention to the sole Asian face he spotted at the event in Demolition Derby, Baker, Montana (fig. 11). The pictured man had been settled in Montana with his wife for some time, both having immigrated from Cambodia. In the photo, he blends in, wearing worn blue jeans, a short-sleeved shirt, and a pocket wallet. Reflecting on his photograph later, Huie states that the Cambodian man appears to be photoshopped into the image. Huie speculates that he may also appear photoshopped into images taken of him in his home state of Minnesota. Being photoshopped into a setting was a good metaphor for not fitting in.24

Huie’s Demolition Derby, Baker, Montana corresponds with his photograph of the Asian American girl at a roadside tourist attraction in Death Valley, CA (see fig. 10). In both images, the Asian American figures do not seem to fit with their backgrounds, whether the predominantly white crowd at the demolition spectacle or the sublime rock formations of the American West. Both pictures give the sense of an alienated awkwardness.

By capturing pictures of the United States while road-tripping cross-country, like several of his predecessors had done, Huie reconsiders and revitalizes the photographic tradition of seeing and identifying the country through automobile travel. Yet, as an Asian American, Huie also sees and experiences things differently from his Euro-American counterparts, who faced far less “othering” during their journeys. It is through his ongoing but largely unplanned search for Asian American subjects, spaces, and communities on the road that Huie was able to identify aspects about himself that he shared with his subjects. His project visually documents his critical reflection on Asian American history and experience as part of his long overdue coming-of-age quest for his own identity. Huie’s work invites the viewer to contemplate the duality, fluidity, and hybridity between the foreign and the familiar that can characterize the Asian American experience along the American road.

Cite this article: Peter Han-Chih Wang, “In Search of Asian-ness in America: Situating Wing Young Huie’s Photographic Road Trip,” in “Reconsidering Art and Travel in America” (In the Round), ed. David Smucker, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18208.

Notes

A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the Association of Historians of American Art Biennial Symposium in the Twin Cities, Minnesota, in October 2018. I want to thank Wing Young Huie for generously sharing his photographs and image permissions with me. In addition, I would like to extend my thanks to David Smucker for organizing this special issue and offering feedback on earlier drafts. I also would like to thank Elizabeth Duquette for providing editorial suggestions during the revision process.

- See Wing Young Huie, preface to Looking for Asian America: An Ethnocentric Tour by Wing Young Huie (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), xvi. ↵

- Most of the Asians on University Avenue and within Frogtown are recently arrived Laotian Hmong refugees, and the Hmong are the area’s largest ethnic minority, making up about a quarter of the population. See Wing Young Huie, “A Frogtown Introduction,” in Frogtown: Photographs and Conversations in an Urban Neighborhood (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1996), 1–2. ↵

- Wing Young Huie, “Joe Huie,” Lake Superior Port Cities 1, no. 2 (1979), 9. See also Wing Young Huie, prologue to Chinese-ness: The Meanings of Identity and the Nature of Belonging (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2018), 9. ↵

- Huie, quoted in Anita Gonzalez, “Autobiography and Ethnocentricity,” in Looking for Asian America, xxii. ↵

- Wing Young Huie, email interview with the author, October 3, 2018. ↵

- The exhibition at the Minnesota Museum of American Art ran from April 17 through August 1, 2004, and Looking for Asian America: An Ethnocentric Tour by Wing Young Huie was published in 2007 as an extension of the exhibition. See Gonzalez, “Autobiography and Ethnocentricity,” xxiv. Huie recalls that he took 186 rolls of film with thirty-six frames per roll, ultimately selecting 111 photographs for the book. Wing Young Huie, email interview with the author, September 7, 2023. ↵

- Originally, Wing wanted Tara’s name in the exhibition title, but she adamantly refused. The project was collaborative on many levels, as Wing and Tara would meet most of the people they encountered on the road together and interacted with them as a couple. The journal, however, was solely Tara’s observations and reflections. Huie, preface to Looking for Asian America, xvii. ↵

- Tara Simpson Huie, “Views from the Road,” in Looking for Asian America, 87–107. See also Huie, preface to Looking for Asian America, xvii–xviii. ↵

- Huie, preface to Looking for Asian America, xviii. ↵

- Wing Young Huie, email interview with the author, October 3, 2018. ↵

- See Wing Young Huie, foreword to Gordon Parks, A Choice of Weapons (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010), xiii. ↵

- Huie, foreword to Parks, A Choice of Weapons, xii–xiii. For the photographic project about Frogtown, see Huie, Frogtown. Huie used the term “acculturation” rather than “assimilation,” since the change of values are not required, and the process is bi- rather than unidirectional. That is to say, to Huie, Asian Americans still try to preserve their original traditions, customs, and cultural values to a degree as they blend with US society. For a classic discussion on the comparison between acculturation and assimilation, see Raymond H. C. Teske Jr. and Bardin H. Nelson, “Acculturation and Assimilation: A Clarification,” American Ethnologist 1, no. 2 (May 1974): 351–67. ↵

- Huie, email interview with the author, October 3, 2018. ↵

- For example, after taking a teaching position at the University of Tennessee, Baldwin Lee conducted a series of road trips in the South from 1983 to 1988, primarily photographing African American subjects. Although both Huie and Lee are Chinese Americans photographing the United States while on the road, their intentions, subjects, and approaches differ since Huie was documenting Americans who shared an Asian identity with himself. Lee’s project, which focused on African Americans in the South, was dormant until 2022, when he held a solo exhibition at the Howard Greenberg Gallery. See Baldwin Lee, “Black Americans in the American South, 1983–89,” lecture, Robert C. May Photography Lecture Series, University of Kentucky, March 24, 2023 (recorded by the University of Kentucky Art Museum). In fact, Huie did not know of Lee’s work until he read about it in the New York Times: Margaret Renkl, “The Troubling and Humane Photography of Baldwin Lee,” New York Times, October 31, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/31/opinion/baldwin-lee-photography-black-america.html. Huie, email interview with the author, September 7, 2023. For more on Lee’s project, see Baldwin Lee, Baldwin Lee (Long Island City, NY: Hunters Point, 2023). ↵

- For Huie’s personal reflection on basketball and the Buddha, see “From the Archive–Loring Park, Minneapolis, Minnesota (circa 1995),” (k)now: a blog by Wing Young Huie, accessed May 19, 2023, https://know.wingyounghuie.com/page/4. ↵

- Michael Jordan returned to NBA at the age of thirty-eight in 2001. Larry Bird once commented, “I think he’s God disguised as Michael Jordan”; quoted in Juan Paolo David, “That Was God Disguised as Michael Jordan,” Sportskeeda, November 8, 2022, https://www.sportskeeda.com/basketball/news-revisited-that-god-disguised-michael-jordan-larry-bird-recalls-mj-s-legendary-63-point-performance-the-garden-1986. ↵

- Shore quoted in Bob Nickas, introduction to American Surfaces (New York: Phaidon, 2005), 9. Shore emulated Frank’s cross-country road trip as a means to fully explore the United States with a snapshot approach in color and with a Pop-art attitude toward mundane subjects that he picked up after working in Andy Warhol’s studio. In his second book, Uncommon Places, Shore switched from a thirty-five-millimeter camera to a four-by-five and eventually an eight-by-ten view camera to provide more analytical viewing and better image quality with details. See Stephen Shore, Uncommon Places: The Complete Works (New York: Aperture, 2004). ↵

- Between 1965 and 1967, Shore was a regular in-house photographer at Warhol’s studio in Manhattan, called the Factory, where he took pictures of diverse groups of people and Warhol’s daily social and artistic activities. ↵

- Huie, interview with the author, October 3, 2018. ↵

- In 1913, California enacted the Alien Land law, barring Asian immigrants from owning land. The state then tightened the law further in 1920 and 1923, barring the leasing of land and land ownership by American-born children of Asian immigrants. The animosity and discrimination against Asian Americans was brewing nationwide, as Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming all enacted discriminatory laws restricting the rights of Asian American to hold land in America. See “California Law Prohibits Asian Immigrants from Owning Land,” EJI: A History of Racial Injustice, accessed May 19, 2023, https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/may/03. ↵

- Huie, “Ping” in Looking for Asian America, 44. For more details, see Tara Simpson Huie, “Views from the Road,” section titled “Carlsbad Mafia,” 106. ↵

- On the 1871 murder of eighteen Chinese Americans in Los Angeles, see Scott Zesch, The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). For the San Francisco riot of 1877, see Katie Dowd, “140 Years Ago, San Francisco Was Set Ablaze during the City’s Deadliest Race Riots,” SFGate, July 23, 2017, https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/1877-san-francisco-anti-chinese-race-riots-11302710.php. For the Rock Springs Massacre in 1885, in which twenty-eight Chinese American miners were killed, fifteen wounded, and the Chinatown neighborhood of Rock Springs, Wyoming, burnt to the ground, see “The Rock Springs Massacre,” History, April 13, 2021, https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/rock-springs-massacre-wyoming. For the Los Angeles riot of 1992, see Kyung Lah, “LA Riots Were a Rude Awakening for Korean-Americans,” CNN, April 29, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/28/us/la-riots-korean-americans/index.html. ↵

- Huie, “Bruce Lee” in Looking for Asian America, 40. ↵

- For Huie’s reflection, “From the Archive—Demolition Derby, Baker Montana, 2001,” (k)now: a blog by Wing Young Huie, accessed May 16, 2023, https://know.wingyounghuie.com/post/20941358050. ↵

About the Author(s): Peter Han-Chih Wang is Assistant Professor in the School of Art and Visual Studies at the University of Kentucky.