“It’s in My Mind”: William Merritt Chase and the Imagination

In some respects, the research methods I use as a curator are the inverse of those of a graduate student writing a dissertation. While in the past I skipped over works of art that did not fit into my narrative and sought out the best examples to make my point, I now tend a permanent collection and have become better at taking the idiosyncrasies of those artworks as the starting point for research. In particular, curatorial work has made me attuned to those moments when artists work against the grain of habit and do something unpredictable. They make one offs, or two offs, and then return to what they were doing before. Trying to square these oddball works against thoroughly convincing interpretations of the rest of the oeuvre can be a fruitless exercise. At the Huntington, there is one such painting by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916),The Inner Studio, Tenth Street (fig. 1), which offers a counter narrative to prevailing interpretations of his work.1

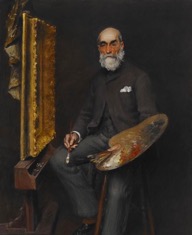

From the Gilded Age to the present, Chase has not been known for the poetic or the chimerical. As Royal Cortissoz put it: “It was [Chase’s] virtue that he kept his eye on the object and painted it as he saw it . . . . Of imagination he never revealed even the slightest trace.”2 More recently, Sarah Burns has characterized his art, in particular the paintings of his New York studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building, as the “paradigm of the aesthetic commodity: the luxuriously coated surface, the precious object celebrating the joys of seeing a material world full of delectably lovely things.”3 Chase as a materialist bound to what he can see, to the glittering surface of things, and his paintings is not challenged here. Instead, I make the modest claim that from time to time Chase pushed against this characterization. The Inner Studio, Tenth Street and Self Portrait in 4th Avenue Studio (1916; Richmond Art Museum, Indiana) (fig. 2) are separated by over thirty years, but each contain an unfinished canvas smattered with marks that do not add up to anything recognizable. No forms or possible subjects emerge. As will be shown, the trope of the unfinished canvas testifies to an inner vision not tied to visible appearances. According to Cortissoz, there was at least a “trace” of imagination, and perhaps on occasion, the artist could not paint it as he saw it because there was nothing to see but a cloud of brush marks.

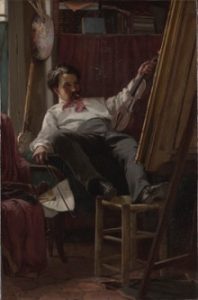

The earliest instance of an unfinished canvas appears to be the Huntington painting. In the painting, a man in spats with dark brown hair, a short hair style, and a tuft of a mustache is seated on a stool, taking in the framed canvas with its nebulous confection of blue, green, and red (fig. 3, and fig. 4 for detail of facial hair). A red covering is partially flipped over the frame as if it had been only recently and haphazardly removed. A print slightly curls as it rests next to the stool, perhaps having been put down moments ago. Its precarious position must be temporary. Sitting uncomfortably close to the painting and with his head turned down, the man cannot take in the entire composition and might be examining a detail. His proximity to the painting is underscored by the shadow he casts on the gilded frame. The man is thinking, not doing, contemplating the canvas that is waiting to be formed by someone. Whether it is by this man or someone else, this painting-to-be is potentiality waiting for an additional intervention to give it shape. Invisible conception will eventually be channeled into visible execution.

Claiming that the unfinished painting in The Inner Studio,Tenth Street is a statement about the invisible imaginative labor of an artist contradicts the critical consensus that had developed around Chase as early as the 1870s. By then, he was already classed as an unpoetic artist grounded in the material world.

In 1887, a reviewer of a Boston exhibition said that Chase has “such happy unconsciousness that art has any ulterior objects, any moral mission or historical function!”4 Another wrote that “[W]hatever [the] eye can see, he is able to comprehend and reproduce.”5 In 1881, the influential critic Mariana Van Rensselaer pointed out: “I do not think that Mr. Chase will ever prove that he possesses imagination of the idealizing sort that can sometimes vitalize the most alien materials and make them valuable.” She adds: “He is not a dreamer of dreams, or a seer of visions, or a romancer, or an idealist of any sort.”6 To be clear, this was not a detriment. She lauded his work and placed him within the lineage of Diego Velázquez and Frans Hals. Whether or not this is Chase, The Inner Studio, Tenth Street is a pictorial retort to the likes of Van Rensselaer. Whoever he is, this man is a “seer of visions” who is vitalizing “alien materials” owing to the prompting of the painting.

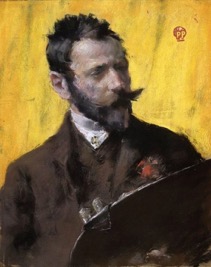

Beyond the inference that the unfinished painting is by Chase because it is in his studio, there is good reason to suspect the artist depicting himself. First, what can be read as a tuft of hair matches his waxed mustache. Second, the man is wearing spats, a signature part of Chase’s costume . Third, the short hair matches that of a self portrait in pastel from 1883. Finally, a critic in 1882 assumed the man in The Inner Studio, Tenth Street was Chase.7 Moreover, the critic read it as a meditation on the mental nature of artistic creation:

The large picture by Chase shows a portion of his studio, with everything thrown about in a haphazard way, displaying a truly inspired disregard of composition on the part of the artist. Of course a studio by Chase, with Chase left out, would be like “Hamlet” with the Dane omitted, and Chase is seen with his back turned on an unappreciative world.8

The melancholic Chase is like Hamlet brought to inaction by his thoughts. In the canon of English literature there can hardly be a better figure to epitomize a division between thought and action.

There are precedents for portraits of artists immersed in the intellectual effort of creating a painting. In a portrait from the 1870s, Chase depicted Frank Duveneck lost in thought instead of in the act of painting (fig. 5). Legs sticking out and slouching with his head resting on his hand, his brush and palette are at rest. Part of a cohort of American artists studying in Munich, Duveneck and Chase traveled together in Italy and shared rooms in Venice.9 Nearly perpendicular to the picture plane and almost bisecting the canvas, the object of Duveneck’s attention is out of view, yet it gives structure to the composition. A Thomas Hovenden self portrait from his bohemian youth in Paris also contains a painting out of view (fig. 6). Hovenden reflects on the fickle nature of inspiration. Holding a bow in one hand and a violin in the other with a burning cigarette in his mouth, the artist sprawls lazily in a position not conducive to playing the instrument or to painting. In a state of languorous distraction, he stares at the unseen canvas. Smoking, his mind gnaws away at an aesthetic problem while his body is at rest.

Around the time of The Inner Studio, Tenth Street Chase represented himself and another artist, Worthington Whittredge, at work on a painting that is placed so the back or side are the only visible parts. The artwork is treated like an object, a stretched piece of canvas, instead of a window into a fictive world. For example, in his portrait of Whittredge, another occupant of the Tenth Street Studio Building, a highly foreshortened frame juts out (fig. 7). There is also a pastel self portrait of Chase at work, either holding a palette or a stiff board on which a sheet of paper is held while he draws (fig. 8). A painting seen from behind or only in partial view is common in portraits of artists at work, as in two extraordinarily famous examples: Rembrandt van Rijn’s Artist in His Studio (1628; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656; Museo del Prado).

The painting in the Rembrandt is wholly obscured, but owing to a mirror, the subjects of the Velázquez painting, Phillip IV and Queen Mariana, are visible. While the unfinished canvas in The Inner Studio, Tenth Street and the unseen canvas in the Whittredge portrait seem unrelated, they accomplish the same end. Both prevent identification of the subject matter of the painting-within-a-painting and, therefore, divert attention toward the artist at work, whether engaged in manual or intellectual effort. It is as if the artistic process is best seen with the object of its labor out of sight.

The unfinished canvas in the Huntington painting is part of Chase’s broader gambit in the 1870s and early 1880s to present himself as a cosmopolite. As John Davis has recently argued, Chase adopted a diverse set of subjects and painting styles as well as sought out exhibition opportunities in Europe in an effort to position himself as an international artist—a strategy that is unsurprising given the high prices American collectors were willing to pay for European artists.10 The Inner Studio, Tenth Street could therefore be yet another vehicle to assert his sophistication. Indeed, the formlessness of the unfinished canvas has precedents in Leonardo da Vinci and James A. M. Whistler, two famous artists who factor into the long history of images made by chance chronicled by H. W. Janson and more recently Dario Gamboni. Leonardo and Whistler, an old and a modern master, championed the indistinct as a legitimate part of art making.

The Huntington studio interior composition hints at a landscape with blue in the upper half and green in the middle, and calls to mind a passage from Leonardo’s On Painting about seeing a landscape in the splattering of paint on a wall. This quote comes from an awkward English translation published in 1802:

A painter cannot be said to aim at universality in the art unless he love equally every species of that art. For instance, if he delight only in landscape his can be esteemed only as a simple investigation; and, as our friend Botticello remarks, is but a vain study; since, by throwing a sponge impregnated with various colours against a wall, it leaves some spots upon it, which may appear like a landscape. It is true also, that a variety of compositions may be seen in spots, according to the disposition of mind with which they are considered; such as, heads of men, various animals, battles, rocky scenes, seas, clouds, woods, and the like. It may be compared to the sound of bells, which may seem to say whatever we choose to imagine. In the same manner also those spots may furnish hints for compositions though they do not teach us how to finish any particular part and the imitators of them are but sorry landscape painters.11

Chase knew this story even if he never read Leonardo. Barbara Novak points out that On Painting was “by far the most popular book” in the library at the National Academy of Design, where Chase studied in the early 1870s.12 Moreover, Chase copied Modesty and Vanity, which was a widely admired painting in the nineteenth century believed to be by Leonardo, but is now attributed to Bernardino Luini.13

The story by Leonardo is one source for the unfinished canvas, but closer at hand is Whistler. Although Chase did not meet Whistler until the summer of 1885, he knew about and promoted the artist’s work, successfully advocating for the inclusion of Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother (1871; Musée d’Orsay) in the 1882 Society of American Artists exhibition.14 More to the point, splattered paint was the central image for the infamous libel trial between Whistler and the critic John Ruskin, who accused the artist of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” What Ruskin derided as a sham, Whistler defended as genius. In a manner of speaking, the trial hinged on proving the legitimate poetic and artistic potentiality of indistinct painted forms. New Yorkers followed the trial, and the New York Times ran an article, “Flinging Paint in the Public’s Face,” which complained that “nowadays it is too much the custom to present vague outlines, suggestions of bulky forms, shadowy indications of an unseen presence, and the mere framework of a phantasm.”15 Chase could have left the canvas blank or roughly sketched out a subject. Instead, he chose to slap on a mélange of marks, a timely image asserting the power of an artist’s inner vision that discerned forms where others saw only disorder or, in the case of Ruskin, fraud.

A final context for understanding the unfinished canvas in The Inner Studio, Tenth Street is the Society of American Artists, a rebel exhibition society that was formed in response to the undiscerning standards and unfriendliness to younger artists of the National Academy of Design.16 Founded in 1877, Chase joined the society in 1879, shortly after returning from his studies in Munich. The society wanted to de-provincialize American art, consequently the inclusion of Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1 in 1882, where The Inner Studio, Tenth Street also hung.17 By including an unfinished painting, Chase nodded towards the notorious Whistler, an artist whose reputation had been secured abroad, and, therefore, a way to stake a claim as a cosmopolitan artist with European credentials.

While the context of the early 1880s factor into his inclusion of the unfinished canvas, this set of circumstances have less explanatory significance later in his career. Like a tale retold too often so that messy details give way to unencumbered narrative momentum and clarity, the meaning Chase ascribes to the unfinished canvas becomes settled. When the empty canvas is mentioned in an 1899 interview, Chase’s ready response suggests that it is something that had been discussed many times before, perhaps in front of classes. Over fifteen years after The Inner Studio, Tenth Street, it is no longer a marker of sophistication, but a reminder that he is less tied to nature and to the visible world than before. When the interviewer asked him about his “best picture,” the artist says: “My best picture? In my studio there is an empty canvas. My best picture is painted there. It’s in my mind. I am always painting my best picture.”18 There can be no doubt that Chase means painting as a mental activity: “‘If I could only paint the pictures in here,’—and the artist touched his forehead. ‘I don’t suppose, though, that I ever shall.’” Indeed a few paragraphs earlier, he calls attention to a change in approach: “I thought that Nature was master. Now I know different. Art transcends Nature. One must paint what is behind the eye of the artist.”19 Not only was he not bound to what he saw, but his mind—not nature—held an inexhaustible wellspring of future paintings. Published in 1917, the Katherine Metcalf Roof biography of Chase also mentions an unfinished canvas: “In his mind, there remained always the distance between his ideal and his achievement, a deep feeling expressed once when, after showing a number of his pictures to a guest, he pointed to a blank canvas. ‘But that is my masterpiece,’ he said, ‘my un-painted picture.’”20

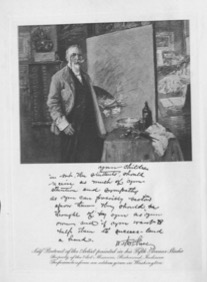

The final appearance of the unfinished canvas is in the 1916 Richmond late Self Portrait in 4th Avenue Studio, which was chosen as the frontispiece for the Roof biography (fig. 9). He wears a smock while holding a palette, brushes, and rags. A ceramic bowl contains turpentine poured from the bottles on the table. Still more rags are piled up to clean brushes. Like The Inner Studio,Tenth Street the marks on the unfinished canvas do not add up to anything. A museum professional with the Art Association of Richmond, Indiana, Ella Bond Johnston, was responsible for negotiating the commission with Chase. In the 1930s, she reminisced that Chase told her that he had wanted to title it My Masterpiece but did not because “people would not understand that the title referred to the empty canvas.”21 The empty canvas was meant to represent “the alluring, tantalizing great picture which I always hoped to paint and have never succeeded in creating.”22

From the early 1880s to 1916 is a long time, a whole career, and it is no surprise that the role of the unfinished canvas shifted. The one time revolutionary call for a loosely rendered Whistlerian painting was retardataire by the 1910s. The unfinished canvas went from a polemical rebuttal to critics to a sagacious sign to a middle aged artist of his limits. There was always a masterpiece around the corner, but Chase professed that he never exactly made the turn. In one of his last paintings, he features a yet-to-be-realized masterpiece, as if to declare his unrealized aspirations but also to remind his admirers that there was more to his art than could be taken in by material vision.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1591

Notes

- As is the case for anyone working on Chase, this essay is indebted to Ronald G. Pisano’s meticulous catalogue raisonné, in particular, entries I.3, I.16, OP. 586, and C.16; see Ronald G. Pisano, completed by D. Frederick Baker and Carolyn K. Lane, The Complete Catalogue of Known and Documented Work by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). ↵

- Royal Cortissoz, American Artists (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1932), 163–69. ↵

- Sarah Burns, Inventing the Modern Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 68. ↵

- Greta {pseudo.}, “Art in Boston: William M. Chase’s Exhibition,” The Art Amateur 16, no. 2 (January 1887): 28. ↵

- “The William M. Chase Exhibition,” Art Amateur 16, no. 5 (April 1887): 100. ↵

- Mariana Van Rensselaer, “William Merritt Chase, Second and Concluding Article,” American Art Review 2 (1881): 141. ↵

- A second critic suggested the figure might be Chase. See “Art in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1882, 22. ↵

- The Fine Arts,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 16, 1882, 4. ↵

- Giovanna Ginex, “From Venice to Venice: Chase in Italy,” in Elsa Smithgall, Erica Hirshler, et al., William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master (Washington DC: The Phillips Collection in association with Yale University Press, 2016). ↵

- John Davis, “William Merritt Chase’s International Style,” in Smithgall, Hirshler, et al, William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, 47–61. ↵

- A Treatise on Painting by Leonardo da Vinci, trans. and ed., John Francis Rigaud (London: J. Taylor, 1802), 199. ↵

- “Introduction,” in Barbara Novak and Annette Blaugrund, eds., Next to Nature: Landscape Paintings from the National Academy of Design (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), 14. ↵

- In Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei (1893), Giovanni Morelli attributed it toBernardino Luini. Chase visited Milan in 1903 to see The Last Supper, another indication of his appreciation for Leonardo, see Giovanna Ginex, “From Venice to Venice: Chase in Italy,” in Smithgall, Hirshler, et al., William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, 74. ↵

- Jennifer Martin Bienenstock, “The Formation and Early Years of the Society of American Artists: 1877–1884,” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 1983), 131–32, and 146, n. 35. ↵

- “Flinging Paint in the Public’s Face,” New York Times, December 15, 1878, 6. ↵

- For an argument in favor of the exclusivity of the SAA, see Saul E. Zalesch, “Competition and Conflict in the New York Art World,” Winterthur Portfolio 29 (Summer/Autumn 1994): 103–20. For an exhaustive study of the early years of the society, see Bienenstock, “The Formation and Early Years of the Society of American Artists: 1877–1884.” ↵

- “The Fine Arts,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 16, 1882, 4. ↵

- Benjamin Northrop, “A Famous Artist’s Struggle Upward,” Los Angeles Times, January 15, 1899, 3. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Katherine Metcalf Roof, The Life and Art of William Merritt Chase, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1917), 321. ↵

- Ella Bond Johnson, “Acquiring a Self Portrait,” Parnassus 8 (March 1936):16. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

About the Author(s): James Glisson is Interim Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator, American Art at The Huntington Library, Art Collection, and Botanical Gardens.