Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock

Amy Werbel

New York: Columbia University Press, 2018; 408 pp. Hardcover $35.00 (ISBN: 9780231175227); e-book $34.99 (ISBN: 9780231547031)

In a 1957 ruling, the United States Supreme Court held that the First Amendment does not cover obscenity. Writing for a six-justice majority in Roth v. United States, Justice Brennan announced that obscene material and utterances do not qualify for the protections provided by the Constitution’s guarantee that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press,” noting that “as early as 1712, Massachusetts made it criminal to publish ‘any filthy, obscene, or profane song, pamphlet, libel or mock sermon’ in imitation or mimicking of religious services.” Brennan reasoned that such laws revealed the existence of “certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and the obscene.”1

In a 1957 ruling, the United States Supreme Court held that the First Amendment does not cover obscenity. Writing for a six-justice majority in Roth v. United States, Justice Brennan announced that obscene material and utterances do not qualify for the protections provided by the Constitution’s guarantee that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press,” noting that “as early as 1712, Massachusetts made it criminal to publish ‘any filthy, obscene, or profane song, pamphlet, libel or mock sermon’ in imitation or mimicking of religious services.” Brennan reasoned that such laws revealed the existence of “certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and the obscene.”1

Reading the Roth case, I have often wondered about the Court’s decision to turn to eighteenth-century colonial jurisprudence to deal with the issue of twentieth-century mail-order pornography. “Who invited the descendants of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to oral argument?” I have snapped out loud. In her excellent new book, Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock, Amy Werbel answers this question and more. With her meticulously researched study of Comstock’s life and work, Werbel provides both a biography of America’s most dogged anti-smut crusader and a terrifically concrete account of the warring effects of censorship in this country.2 In the process, she demonstrates the deep influence that the Puritan origins of the nation continue to exert on our legal and social understandings of the obscene.

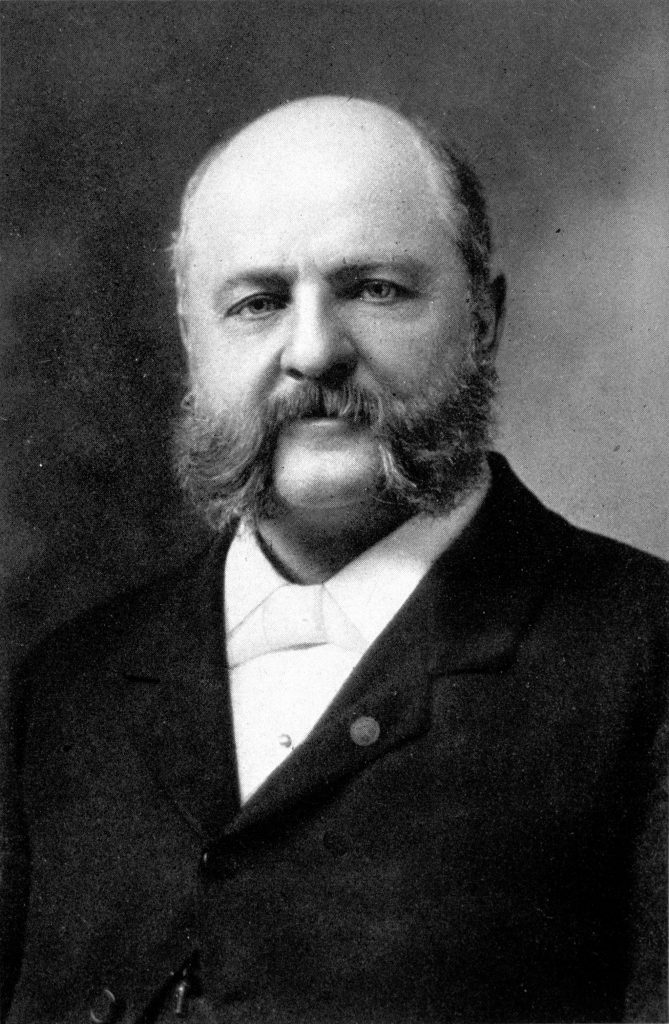

Anthony Comstock (1844–1915; fig. 1) always claimed to have gotten into the erotica-extermination business as the result of the pornography-related death of a young man he had once known. Whether this rationale is true remains uncertain. What Werbel makes abundantly clear is that Comstock was willing to go to the mat to destroy any sex-related material that offended him. (Spoiler alert: most of it did.) During the more than forty years he spent riding herd over American morals and mails—first as a private citizen and then as a special agent for the US Post Office Department—he was threatened by countless people, punched in the face by a lawyer, thrown down a flight of stairs by one erotica-monger, and stabbed to the bone by a second. Reading Werbel’s book, one gets the sense that numerous others would have enjoyed taking a shot at Comstock, including Walt Whitman, Thomas Eakins, Margaret Sanger, the Art Students League of New York, the better part of the New York defense bar, and the collective membership of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. None of this, however, deterred Comstock in his efforts to impose the standards of his own evangelical upbringing on the country between roughly 1867 and his death in 1915 (fig. 2). “If die I must, I want to die with the harness on, fighting the enemy of the youth of our beloved lands,” he proclaimed in an 1875 letter to a senior post office official (76). As Werbel observes in her wonderfully wry style, “This was not a typical report from a postal inspector” (76).

Werbel begins her narrative on Comstock’s rather tumultuous life with attention to his profoundly pious childhood in the Congregationalist stronghold of New Canaan, Connecticut. She charts his development from a masturbation-phobic schoolboy to a Manhattan dry goods clerk to the trench warrior and public face of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). Comstock quickly gained national attention and tremendous political clout by taking aim at “feisty women” such as Sanger, as well as the captains of New York City’s smut industry (77). In 1873, he played a central role in motivating Congress to pass the appropriately named “Comstock Act,” a sweeping piece of legislation that, as Werbel discusses, both expanded and focused the target of American anti-obscenity prosecutions. Combined with Comstock’s success in convincing American courts to adopt the British Hicklin test, from Regina v. Hicklin (1868), which defined obscenity as any material with a “tendency. . . to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands publication of this sort may fall,” Comstock’s eponymous act effectively outlawed any material that a judge or twelve jurors could imagine sparking unacceptable sexual desire in those with a predilection for such wayward delights.3 “Obscenity under the new law did not require proof of public endangerment, or even of individual physical, mental, or emotional harm,” Werbel writes; “now, lust inducement itself was a violation of the law” (72). It was, in other words, Comstock, along with the upper-class evangelicals who backed him, who installed Cotton Mather and his decidedly unbacchanalian brethren as the resident ghosts in America’s obscenity machine. Comstock reached the height of his power in 1883. After this, he devolved into something of an American caricature, the nation’s collective shorthand for “rabid prude.” Reading Lust on Trial, one learns that this fall from grace stemmed in part from his tripartite inability to cooperate with other moral reformers, especially women; to keep up with the technological developments that allowed Americans to stimulate and satisfy their desires in constantly evolving ways; and to respect the class lines that have historically structured Western definitions of the obscene. It is with this last insight that Werbel makes some of her best observations. Admittedly, the idea that obscenity is a problem of audience as much as subject matter is not new. As Walter Kendrick demonstrated in The Secret Museum: Pornography in Modern Culture, the very notion of pornography first came into being when advances in print technology allowed sexually provocative material to escape from the rarified realm of the upper classes and reach the supposedly undereducated, oversexed masses who lacked the intellectual and moral framework necessary to consume such words and images without succumbing to the pleasures of the flesh.4 Werbel makes an important contribution to this history by tracing the specific effects such class anxieties had on the boundaries of “the lewd and the obscene” in American art, law, and culture.

Comstock’s own biography played a key role here. As Werbel recounts, America’s best known combatant of vice was, first and foremost, “a foot soldier” for organizations such as the NYSSV and, before it, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) (57). His primary mission was therefore to do “the ungentlemanly work” that the patrician members of such groups—not to mention Congress—could not undertake without compromising their station (55). Such white-shoe men certainly enjoyed consuming the spoils of the Comstock raids—as demonstrated by their eagerness to get a look at the pictures, advertisements, sex toys, and other lascivious items he confiscated—but they could not be seen loitering in the neighborhoods that their middle-class henchman necessarily frequented. Conversely, Comstock could not poke too aggressively into their rarified, upper-class world without risk of losing their support. Which is not to say he did not try. Convinced that “Genius has no more right to be nasty than the common mind” (136), Comstock took aim at the prestigious M. Knoedler & Co. art gallery in 1887 and the Art Students League of New York in 1906, evidence of his rejection of “the idea that wealth was an inoculant to the ‘disease’ of the nude in art” (180). In both cases, Werbel concludes, he “broke the cardinal rule he should have learned earlier, that he should not go after rich people” or the cultural pursuits they valued (190).

Such class incursions precisely led to Comstock’s fall from grace. Before he went, however, he managed to publicize the very material he sought to eradicate. Here again, Lust on Trial shines, as Werbel deftly spins her extensive archival finds into a detailed history of the effects of Comstock’s censorship campaign. Building on the notable work of scholars such as Richard Meyer, Werbel gives a detailed analysis of the precise ways in which Comstock achieved “the neat trick of popularizing both vice and vice suppression,” introducing the reader to a wide roster of people whose businesses and lives were shaped (or, sometimes, destroyed) by their interactions with the grandmaster of American obscenity (211).5 We learn of the writer who hoped that Comstock would “attack [her book] just a little” and thereby help her sales (205); the outraged artists, lawyers, and activists who reacted to Comstock by rallying around the cause of free expression; and the gay men and sex workers who did years of hard prison labor in service of Comstock’s sanctimonious soul. With these examples, Werbel provides concrete evidence for the Foucauldian conception of censorship as a generative force. In the process, she, like Meyer, gives practical traction to an intellectually thrilling theory.

The history of American erotica can be difficult to reconstruct. Unsurprisingly, the double threat of social condemnation and criminal liability often impelled producers of “spicy” texts and images to cover their tracks by omitting such materials from their journals, registers, and personal correspondence. Even when they did not, their relatives often did this work for them, hiding or even destroying such suspect bits of the historical record. Ironically, Comstock’s own ledgers consequently provide some of the best evidence we have of the national habits and tastes in this area. Between 1872 and 1915, he kept a fastidious account of, among other things, the name, offense, arrest date, inventory, and “social condition” of everyone he and the NYSSV pursued. Werbel makes deft use of this valuable resource, transforming Comstock’s three leather-bound volumes of “tight cursive handwriting” from simply a map of who-was-punished-how for buying what and where into an illuminating diagram of precisely what items fell within the forbidden category of the obscene during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (96). Supplementing this archive with a wide variety of legal, journalistic, and art-historical sources, Werbel has produced a book that will be useful for historians of American art, law, and visual culture alike.

As with most books, Lust on Trial comes with its own shortcomings. I found Werbel’s tacit assumption that only men consumed erotica during the period in question particularly frustrating. Discussing the Kinsey Institute’s collection of explicit catalogue cards, for example, she notes “men could choose what most assisted them in achieving arousal and satisfaction” before concluding that such images “illustrate the very diverse tastes and desires of men at the end of the nineteenth century” (228). Although I do not dispute either statement, neither accounts for the fact that women might also have taken pleasure in such pictures. Do such female consumers appear in Comstock’s registers? Did he ever target women pornographers? Did they exist? Given Werbel’s adroit attention to Comstock’s intense discomfort with “women seeking political and sexual empowerment,” I expected more on women’s participation in obscenity—participation that must have exceeded Comstock’s own dichotomy between whorish models and virginal victims (86).

In addition, while Werbel delivers an excellent account of upper- and middle-class American taste for slumming at the turn of the century, particularly their urge to savor fantasies of the less privileged as intoxicatingly feral beings, I wanted some attention paid to the ways in which courtroom antics worked to exacerbate class divide. It strikes me that Hicklin overtly invited this sort of othering of the “depraved” lower classes into the courtroom, tying the legal standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt” to narcotic dreams about how the other half lived. But still, I wanted a deeper analysis of the sort of imaginative work the Hicklin test demanded of the judges and juries charged with determining whether a particular defendant trucked in work that might “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences.” It is a topic Werbel hints at, but does not fully develop.

Neither of my critiques, however, diminish the strength of Lust on Trial. To the contrary, Werbel’s book seems particularly urgent right now. One hundred fifty years ago, powerful groups of upper-class white men sought to stabilize an American world that favored them by anointing Anthony Comstock “a Christian censor of morals within a supposedly secular government position” (12). In the process, they both enabled him to brutalize the vulnerable and called a robust—and ultimately victorious—opposition into being. As Werbel writes, “there certainly are times when a fierce and dogged opponent may in the end be a great gift” (299). I can only hope she is right and that now is also one of those times.

Cite this article: Mary Campbell, review of Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock, by Amy Werbel, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2108), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1670.

PDF: Campbell, review of Lust on Trial

Notes

- 354 U.S. 476 (1957). ↵

- Other works that deal with issues of American obscenity, law, and art include Mary Campbell, Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); John D’Emilio and Estelle Freedman, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America, 3rd edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012); Donna Dennis, Licentious Gotham: Erotic Publishing and Its Prosecution in Nineteenth-Century New York (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009); Andrew L. Erdman, Blue Vaudeville: Sex, Morals, and the Mass Marketing of Amusement, 1895–1915 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Press, 2004); Helen Lefkowitz, Rereading Sex: Battles over Sexual Knowledge and Suppression in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Knopf, 2002); and Richard Meyer, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). ↵

- United States v. Bennett, 24 F. Cas. 1093 (C.C.S.D.N.Y 1879), citing Regina v. Hicklin (1868 L.R. 3 Q.B. 360). ↵

- Walter Kendrick, The Secret Museum: Pornography in Modern Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). ↵

- Richard Meyer, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2002). ↵

About the Author(s): Mary Campbell is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Tennessee