Magic City Modern: A Short History of the Birmingham-Bessemer School

As a site of collective memory, Birmingham, Alabama, is commonly associated with some of the darkest chapters in American history. In his famous 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King, Jr. described the city:

There can be no gainsaying of the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of police brutality is known in every section of this country. Its unjust treatment of Negroes in the courts is a notorious reality. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in this nation. These are the hard, brutal, and unbelievable facts.1

During the Civil Rights era, the increasing demand by black Americans for some semblance of social and political equity ignited long-simmering racial tensions, especially in the city of Birmingham. Demonstrators of all ages put their bodies and livelihoods on the line to protest oppressive Jim Crow laws, which were enforced with particular brutality in the region. Jim Crow laws were also known as black codes, as they were the rules that governed black life. There were, however, other types of black codes that existed throughout the South. In this instance, we may think of a code not as rules but in terms of one of its other meanings: a visual system for communicating information, especially in secret. These other black codes were not ones used to enforce subjugation, but were instead personal and collective expressions. This text addresses the existence of such alternative codes, made manifest in the way that black artists in Alabama created work embedded with complex layers of conceptual meaning and aesthetic content that appeared in their yards and homes, often hidden from the public eye.

This essay specifically serves as an introduction to a group of black male artists living in the greater Birmingham, Alabama, area from the period after the Civil Rights Movement through today. While two of the artists, Thornton Dial Sr. (1928–2016) and Lonnie Holley (b. 1950), have achieved relative institutional and academic recognition, the other two members of this group, Joe Minter (b. 1943) and Ronald Lockett (1965–1998), remain comparatively underrecognized within the history of art and underrepresented on the walls of museums.2 These four artists lived either in Birmingham, the largest city in Alabama, or the smaller adjacent town of Bessemer. They constitute what American studies scholar Bernard L. Herman calls the “Birmingham-Bessemer School.”3 While they did not refer to themselves as such, each artist acknowledges the importance of this small community to their individual practices. All impacted, either directly or indirectly, by Jim Crow rule, Dial, Holley, Lockett, and Minter made works that are not simply documents of history or illustrations but hidden transcripts, visions of alternative futures, and radical archives of black determination. The hard, brutal, and almost unbelievable facts mentioned in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s description of Birmingham—racial injustice, police brutality, bombings—appear in the following works of art but are transformed, abstracted, and coded within the objects themselves.

Even though the Birmingham-Bessemer School was active in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, their collective history is rooted in the circumstances surrounding Birmingham’s founding as a city in the late nineteenth century. In Monument to the Minds of the Little Negro Steelworkers (fig. 1), Dial draws upon the history of Birmingham as the steel and iron manufacturing capital of the South; the industry was propelled by black freedmen who worked in the iron foundries and coal mines of the region. Using primarily scrap metal, Dial has carefully manipulated this material into a swirling morass of curlicue forms. These forms evoke the decorative ironwork (often made by black artisans) seen throughout Southern architecture—reminding viewers that the labor of black Americans is hidden everywhere.4 Additionally, the rags, bones, bottles, and artificial flowers that adorn the work’s metal structure recall black graveyard decorative traditions, an important phenomenon within the larger cultural history of black Americans. Historically, black graveyards were some of the only sites white people dared not enter, allowing them to become some of the earliest spaces for safe visual expression by African Americans.5 Dial, himself a former metalworker, created this monument to, importantly, the intellect of the black workers whose contributions to the technological advancements pioneered in the area have gone unnoticed. Viewed as a whole, Monument to the Minds of the Little Negro Steelworkers is a powerful visual index to the rich history of black life, love, and labor in the greater Birmingham region.

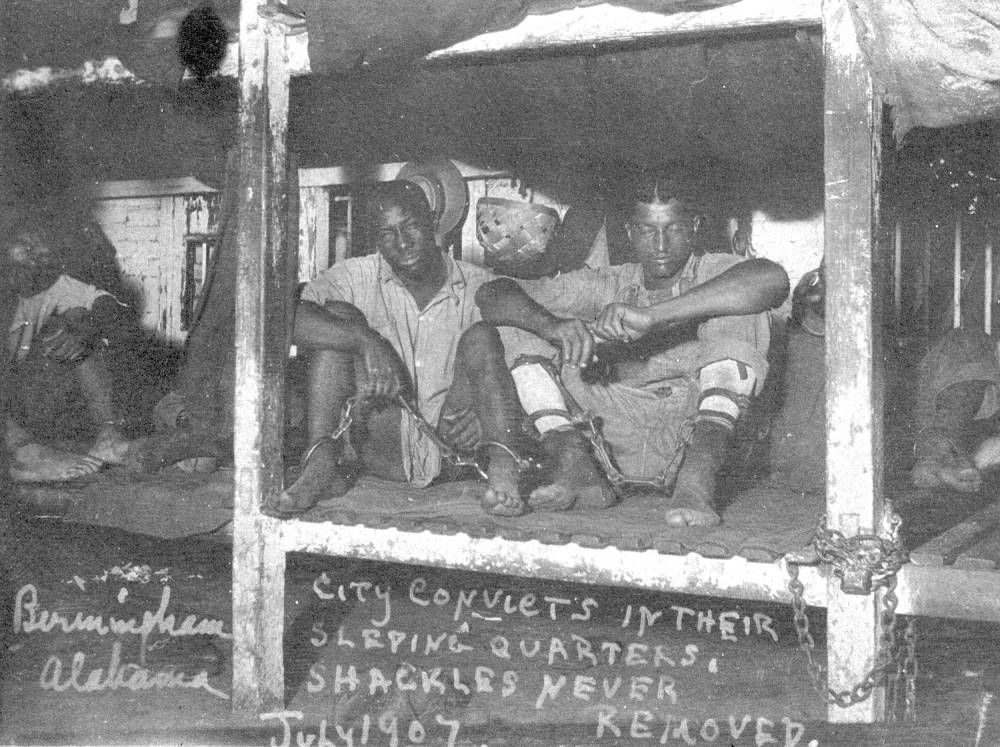

Birmingham was historically referred to as the Magic City because its soil contained the three necessary elements to produce iron: limestone, coal, and iron ore. This geological condition allowed Birmingham to become one of the most successful industrial centers in the post-Reconstruction South, and by the 1880s, it was the steel capital of the Southeast and one of the region’s most urbanized areas.6 Far from any stereotypical vision of a rural Southern hamlet, Birmingham was a city built on its adoption of technological and industrial advancements, instead of relying on agriculture. The steel industry in Birmingham was fundamentally built on the continued violence toward and oppression of black workers. Birmingham was unique in the way that the city factory owners exploited a new form of industrial labor that could be equated to a form of slavery.7 The steel industry and local police force worked in concert to create this system of labor. Police in the Birmingham-Bessemer region would arrest black men for “crimes,” including loitering, vagrancy, or breaking curfew—essentially, being black in a public space—and then funnel them into the convict-lease system, so that they could be used as free labor for the steel and iron industry (fig. 2).

In order to fully understand a work such as Joe Minter’s Chain Gang (fig. 3), it is essential to confront the history of this particular form of oppressive labor. In addition to exploiting a systematically unjust criminal arrangement, factory owners fashioned a caste system for paid laborers in which white workers, a minority of the employees, functioned as skilled labor, while the black workers, who represented the majority, were classified as unskilled labor, with little to no opportunity for upward mobility. The black workers were given the most difficult and dangerous work in the foundries, exposing them to extreme heat, toxic gases, and unforgiving physical labor. Despite these horrific conditions, many African Americans outside of Alabama came to work in these foundries in an effort to escape the pittance of sharecropping.8 By the 1920s, African Americans made up roughly 60 to 80 percent of the steel industry’s workers.9 In Minter’s metal assemblage, farm tools are forever chained together, the tools functioning as stand-ins for human figures, an allusion to the fact that the black body was historically viewed by those in power as valuable only insofar as it can be used for work. The sculpture is created from metal, which was the final product of so much dangerous and backbreaking labor—then, of course, the metal produced could be turned into tools to facilitate more hard labor. Similar to Mel Edwards’s (b. 1937) famous Lynch Fragments series, both artists imbue abstracted metal forms with a sense of malevolence, threat, and history.10

Chain Gang functions as a standalone work, although it also belongs to a larger project Minter has been working on for the last few decades. Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Minter began transforming his property into what he calls, “The African Village in America.” Stretching across the entirety of his one-acre property, it has now become a single-artist museum and art installation dedicated to the history of the black diaspora in the United States. Minter began building this yard after he heard the city was about to begin construction on what is now the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, located in downtown Birmingham. In fearing that the city would not, in his words, “tell the story of his people that has never been properly told,” he embarked on this thirty-plus–year ongoing project.11 As one weaves through his environment—which, as of 2020, can be visited by the public—it is possible to encounter abstract sculptures, such as Chain Gang, as well as found-object recreations of specific sites significant to black history, such as the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, or the Birmingham Jail cell (fig. 4) from which Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote his famous letter (quoted at the beginning of this text).

Minter’s yard is one of the best extant examples of a visual phenomenon that used to exist across the South—the “yard show,” a type of site-specific art environment that was erected primarily by black Americans on their properties. The yard show was especially predominant in the Deep South. Originally defined by Robert Farris Thompson as “the practice of adorning one’s property and living space with objects of aesthetic, spiritual, and cultural significance,” these sprawling installations were filled primarily with found object assemblages, but also paintings and sculptures, and were once commonplace.12 Beyond object adornment, these yards also presupposed the presence of a viewer, or a community within which such a practice could be understood.13 Additionally, yard shows were also a way of announcing ownership through visual expression; this is significant, considering how difficult it was (and still is, in many ways) for black people to own property. Finally, in creating a massive, impossible-to-ignore art environment where visitors must confront American history, these artists present an artistic archive for oneself and one’s community. With the exception of Ronald Lockett, each artist in the Birmingham-Bessemer School constructed a yard environment. What makes Minter’s yard particularly powerful, in addition to its content, is its location: perched on the top of a hill, it overlooks two historically black cemeteries, Shadow Lawn and Grace Hill, where many of Birmingham’s black laborers and citizens are laid to rest. The phenomenon of the yard show has now, for the most part, ceased, as their makers have passed away and black people have moved away from the South.14

Black flight from the South during the period of the Great Migration greatly impacted the cultural, social, and economic landscape of the region. While the Birmingham area was the site of major economic growth in the early half of the twentieth century, by the 1950s, industry jobs began to decline sharply. By 1971, all the Birmingham iron mines had closed. These closures most sharply affected the city’s black population, who held the vast majority of its industrial jobs. The decline of this industry directly impacted Thornton Dial, perhaps the best-known member of the group. Dial had spent thirty years working at the Pullman Standard plant, and his neighborhood, Pipe Shop, was named for its proximity to U.S. Pipe, a major employer in Bessemer. After Dial was permanently laid off, at age fifty-eight, he decided to devote most of his time to art making. Working in his “junk house” studio on Fifteenth Street in the Pipe Shop, Dial began to experiment with making things that had no explicit utilitarian value, although at that stage he did not call these objects art.15 Later, importantly, Dial would embrace his practice and self-identify as an artist.

The early period of Dial’s career (late 1980s through the 1990s) is marked by the consistent presence of animal subject matter. Birds, fish, and, most of all, tigers make frequent appearances. In Dial’s symbolic universe, the tiger served as an avatar for himself, and more generally, the history of black struggle in the United States.16 To the uninformed, the use of the tiger could seem like nothing more than a folksy proclivity, or, even more problematically, an indicator of a primitive connection to nature. In actuality, using the tiger as a symbol for black struggle allowed him to speak about personal and social inequity in a veiled and critical fashion.

For example, in the early work Monkeys And People Love the Tiger Cat (fig. 5), a blue tiger rendered out of rope is surrounded by abstracted human and monkey figures painted in bold strokes of black and white. A snake, a biblical symbol for evil, stretches across the top of the painting. Even at this early phase in his career, Dial was skeptical of the approval he was beginning to receive in the mainstream art world. This scene is a coded expression of Dial’s early apprehension, where the tiger is made to perform for people, whose features, while abstracted, are noticeably rendered primarily in white.

The tiger’s close relationship to the black panther is no coincidence. The Black Panther image originated from Lowndes County, located just outside of Montgomery, Alabama. The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) was formed in 1965 under the umbrella of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), helmed by Stokely Carmichael. As a party, the LCFO had a mission to register the majority black citizens of Lowndes County to vote. They chose the black panther as their symbol, and a year later Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale adapted the image for the newly formed Black Panther Party, based in Oakland, California.17 In looking at the roadside sign for the LCFO, as captured in Jim Peppler’s photograph (fig. 6), the flattened, horizontal orientation of the panther figure, with its upwardly curved tail, bears a striking formal resemblance to Dial’s Monkeys and People Love the Tiger Cat. Dial’s selection of the tiger as an avatar, with its proximity to the panther, allowed him to indirectly associate himself with larger movements addressing black struggle without having to explicitly state his politics.

The animal avatar shows up with particular prominence in the work of another member of the Birmingham-Bessemer School, Ronald Lockett. Lockett was Thornton Dial’s much-younger cousin, who, for a period of time, “studied” under Dial in an unofficial mentor-mentee capacity. Also living on Fifteenth Street, for years Lockett was the only person allowed in the junk house studio while Dial was working. As his protégée, the most significant concept Lockett appropriated from Dial was the use of an animal avatar as an encoded autobiographical figure. As his avatar, Lockett selected not a predator, but prey—a deer.

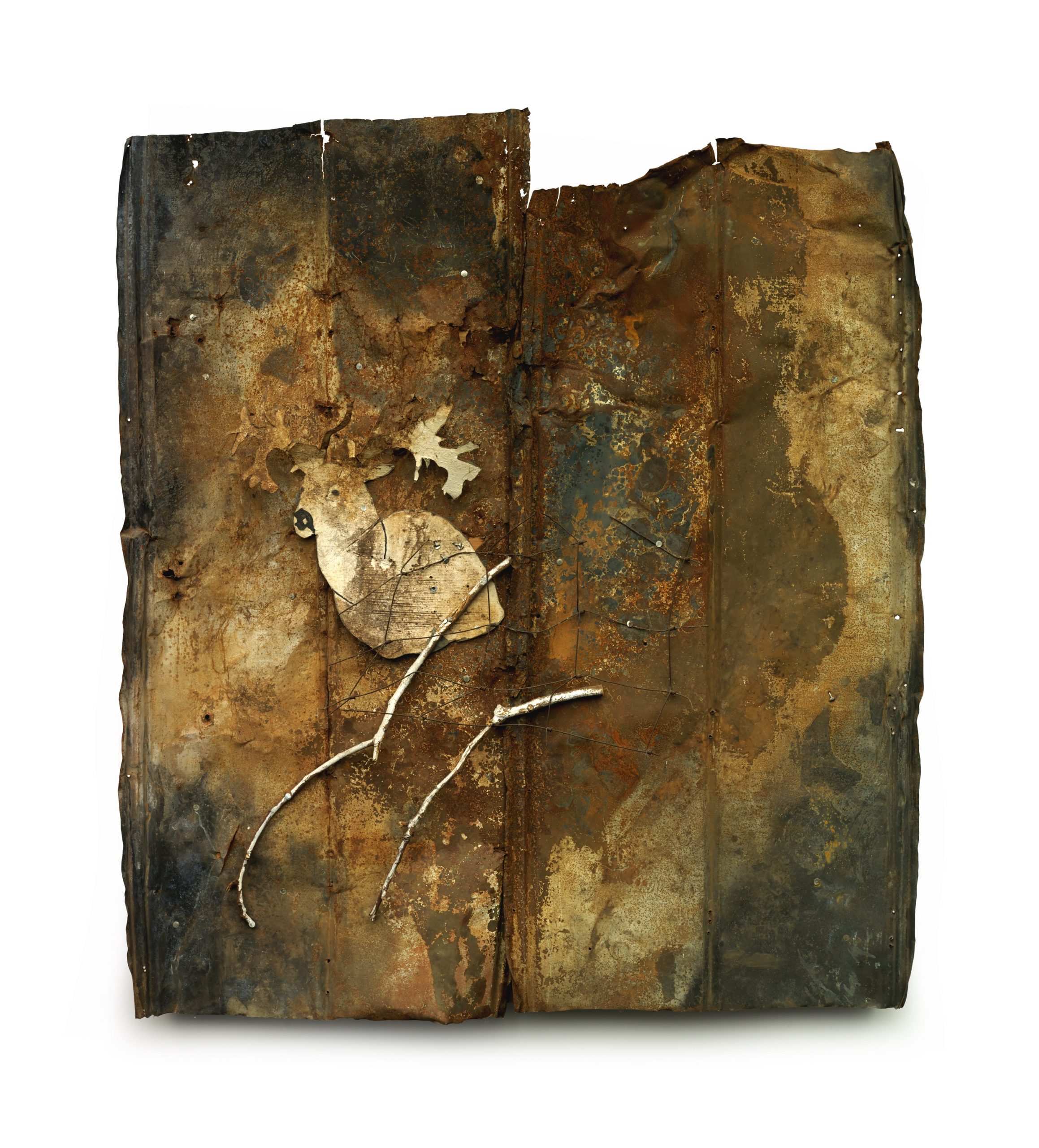

The whitetail deer that often appear in Lockett’s paintings and assemblages (fig. 7) are commonly found throughout Alabama, in both rural and urban areas. In the mid-twentieth century, the Alabama Department of Conservation began cultivating a stock of deer throughout the state.18 Hunting whitetail deer was and continues to be a popular pastime in Alabama; the majority of hunters are white men who live in rural areas.19 Lockett was not a hunter. In choosing the deer as his avatar, specifically, the common Alabama whitetail deer, in effect, he was positioning himself as the locally hunted animal. In choosing an animal of prey instead of a predator, Lockett’s deer are meditations on the difficulty of young black survival in the small postindustrial town of Bessemer, where job opportunities were limited, and, for many of Lockett’s generation, leaving seemed like the only option. In addition, the male deer that appear throughout his work are also an homage to his mentor, Thornton Dial, who was referred to by loved ones as “Uncle Buck.”20

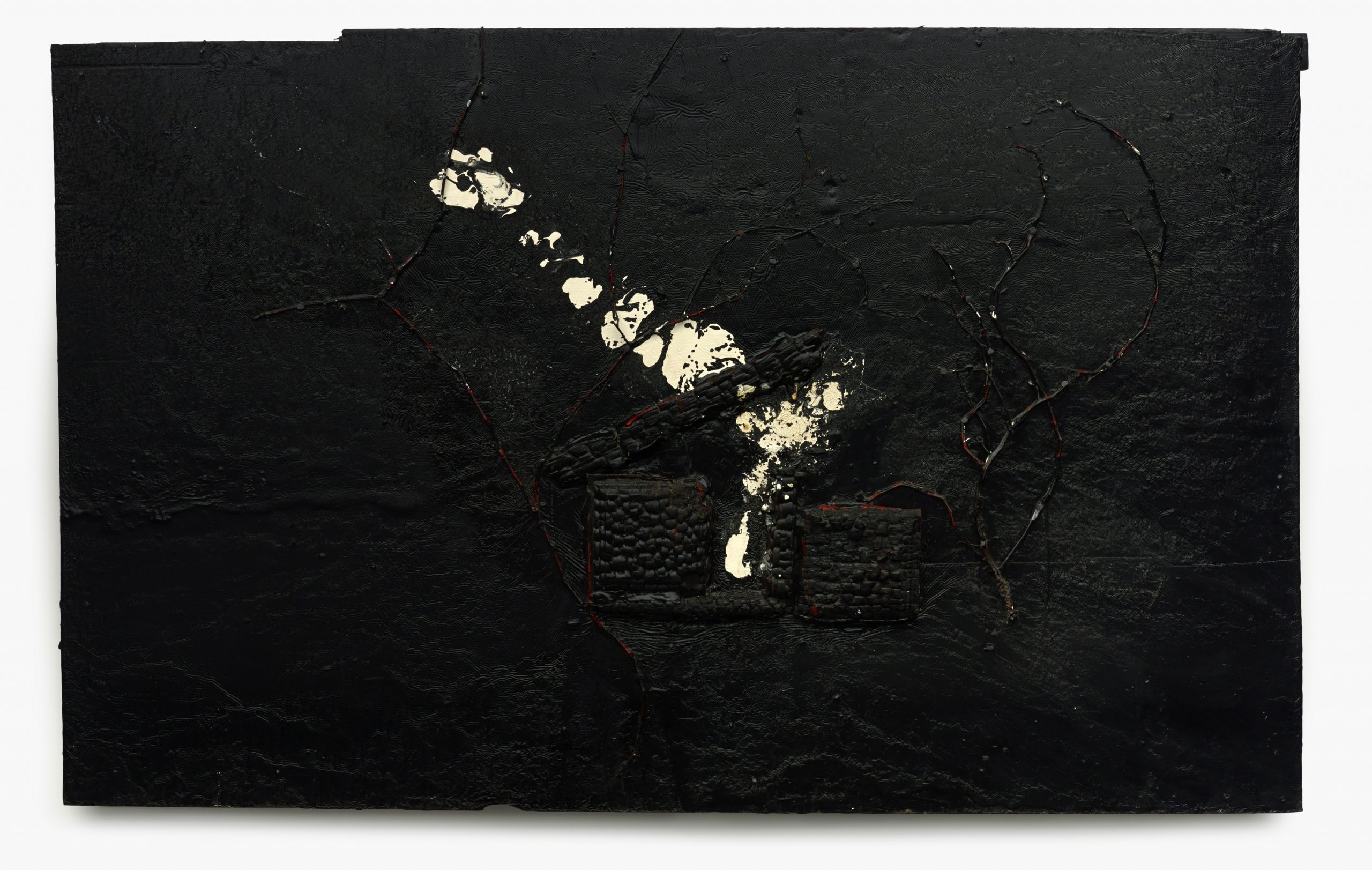

Beyond animal subject matter, Lockett was deeply interested in creating works of art related to the collective history of the area. During the 1950s and 1960s, Birmingham was also called “Bombingham” due to the frequency of bombings committed by white residents, who sought to terrorize the black community and quell any form of uprising and resistance.21 In Smoke-Filled Sky (fig. 8), Lockett takes charred wood, reignited with lashes of red paint, and visualizes this act of violence. As the school’s youngest member, Lockett did not personally experience the effects of Jim Crow or the unfolding of the Civil Rights Movement. Nevertheless, he felt the need to address this shared history in his own practice.

Born in 1950, Lonnie Holley did live through this traumatic period of American history. One of the most significant acts of domestic terrorism, which helped ignite the Civil Rights Movement, was when the Ku Klux Klan bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963, killing four black girls who were changing into their choir robes in the church basement. Holley was thirteen years old when the bombing happened, almost the same age as the four victims. Holley’s grandmother worked as a gravedigger for a portion of her life, and, according to him, she dug three of the four bombing victims’ graves.22 The shovels of Three Shovels to Bury You (fig. 9), with their spades turned upright, have an anthropomorphized presence similar to Minter’s Chain Gang. Both a personal and historical memorial to the people of his hometown, the work serves as another example of how artists of the Birmingham-Bessemer School confront history in a coded manner.

Historically, the consistent use of found materials in the work of the Birmingham-Bessemer School has been attributed to need: with a lack of economic resources, they were compelled to use what was readily available. While this is partially true, these artists are also making very deliberate conceptual and aesthetic choices to further their own visions and artistic practices. Holley’s use of junk and found materials, in particular, needs to be properly understood within his own radical epistemology and the larger history of other black artists who worked with discards. “What I’m doing here, I think Malcolm said it best: by any means necessary,” Holley states, “We can make art where we have to. Dr. King, if you remember, wrote a sermon on a piece of toilet paper.”23 In these statements, Holley connects black history to trash: not by lowering this history to the status of garbage, but instead by unlocking the subversive potential of junk through this association. When Holley states that he makes art “by any means necessary,” he is also alluding to his use of lost or discarded materials. Using junk is a necessary means for Holley as an artist, a practice that grew not only out of a lack of traditional art materials, but also out of a recuperative desire to unlock the historical and aesthetic possibilities embedded in every object. The idea that Dr. King was not above using toilet paper in his own work, that in times of need even the lowliest of household objects was a worthy vessel for a sermon, clearly appealed to Holley. If toilet paper can contain a sermon, then anything can be used to create a work of art.

The South, so often considered the backward and antimodern underbelly of the United States, was nevertheless a site of industrialization—especially the city of Birmingham. As its history reveals, this modernity was built through the continued abuse and oppression of black Americans, a counter to any romantic notions of progress. To fully understand the work of the Birmingham-Bessemer School, Birmingham’s exceedingly violent modern history must be confronted. In this same vein, one must also confront the many unrealized promises of the Civil Rights Movement and the effects of deindustrialization, which led to the economic collapse of the area in the 1970s. It is plausible that part of the resistance to accepting these artists into the larger narratives of modern and contemporary art is due to the ugly historical circumstances that led to the group’s formation in the first place. Their exclusion represents the general resistance in the United States to fully acknowledging the social and political realities that black citizens faced and continue to face.

The city of Birmingham set the stage for the emergence of artists such as Holley, Minter, Lockett, and Dial. With its systematically unequal, exploitative, and racist labor practices, its association with the most violent tragedies of the Civil Rights Movement, and its continued economic challenges, Birmingham exists as a constant reminder of the casualties of economic development and how racial equality is far from having been achieved. Each artist of the Birmingham-Bessemer School uniquely addresses this history through varying media and conceptual orientations. Collectively, they have turned this difficult and challenging past into difficult and challenging art; the school’s story is ultimately one about black self-determination. To borrow a quotation by the historian Robin D. G. Kelley, perhaps the history of Birmingham can best be characterized as: “Here you are watching Western Civilization. It emerges as Modern as can be, but is the best example of Barbarism you’ve ever seen.”24 Speaking in eloquent and subversive visual languages, the work of the Birmingham-Bessemer School reveals the barbaric underside of modernity—but only to viewers willing to crack the codes.

Cite this article: Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Magic City Modern: A Short History of the Birmingham-Bessemer School,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9831.

PDF: Alexander, Magic City Modern

Notes

- Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” 1963, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, CA, accessed March 2, 2020, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/letter-birmingham-jail. ↵

- Any history of Southern black art must begin with the foundational texts by William S. Arnett et al., Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, 2 vols. (Atlanta, GA: Tinwood Books, 2000–2001). ↵

- “Because their conversations {Lockett and Dial’s} over time embraced other artists, including Lonnie Holley and Joe Minter, they define what might be understood as the Birmingham-Bessemer School. Theirs was a school defined by a context of shared knowledge and experience, creative and critical observation, and an open exchange of ideas, often through visits. There was neither institutional framework nor formal curriculum; instead, there was a rich multigenerational practice of demonstration and conversation.” See Bernard L. Herman, “Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die: Ronald Lockett’s Creative Journey,” in Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 17. ↵

- John Michael Vlach, “Blacksmithing,” in The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 108–21. ↵

- Vlach, “Graveyard Decoration,” in The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, 139–47. ↵

- Blaine A. Brownell, “Birmingham, Alabama: New South City in the 1920s,” The Journal of Southern History 38, no. 1 (February 1972): 22. ↵

- For a critical history of this phenomenon, which occurred across the South, see Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (London: Icon, 2012). ↵

- Henry Mckiven, Iron and Steel: Class, Race, and Community in Birmingham, Alabama 1875–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 4, 46. ↵

- Charles E. Connerly, “The Most Segregated City in America”: City Planning and Civil Rights in Birmingham, 1920–1980 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005), 2. ↵

- For more on Mel Edwards and his Lynch Fragments series, see Adriano Pedrosa and Rodrigo Moura, eds., Melvin Edwards: Lynch Fragments (São Paulo, Brazil: MASP, 2018); Nancy Morejón and Carmen Alegría, “Melvin Edwards: The World of a Marvelous Artist,” The Black Scholar 24, no. 1 (1994): 47–50; Sharon Patton, “Melvin Edwards Sculptor of the African-American Ethos,” The Black Scholar 24, no. 1 (1994): 51–55. ↵

- Joe Minter, interview with the author, Birmingham, AL, August 2017. ↵

- Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, (New York: Random House, 1983), 124. ↵

- “The makers of these special yards work to please themselves and to instruct visitors in appropriate behavior, sometimes in the broadest spiritual sense. The work takes personal inventiveness, a cultural repertoire of signs that may be widely known or accessible only through special instruction, and alertness to real-world political, historical, and economic conditions.” Grey Gundaker, “Tradition and Innovation in African-American Yards,” African Arts 26, no. 2 (April 1993): 59. ↵

- Michael Tortorello, “Scrap Iron Elegy,” New York Times, April 24, 2013, accessed March 4, 2018, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/garden/joe-minters-african-village-in-america.html. ↵

- David Driskell, “Giving Into the Visionary Dream: A Visit with Thornton Dial,” Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial (New York: Prestel, 2011), 13. ↵

- Thornton Dial’s first museum exhibition explored Dial’s complex tiger imagery. See Thornton Dial, Amiri Baraka, Thomas McEvilley, Paul Arnett, and William Arnett, Thornton Dial: Image of the Tiger, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the American Folk Art Museum, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, and the American Center, 1993). The exhibition was mounted jointly at two New York institutions: the American Folk Art Museum, where it was shown from November 16, 1993, through January 30, 1994; and at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, where it was shown from November 17, 1993, through January 2, 1994. ↵

- Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981). ↵

- Ralph H. Allen, History and Results of Deer Restocking in Alabama (Bulletin No. 6), (Montgomery: Alabama Department of Conservation, Division of Game and Fish, State Management Section, 1965). ↵

- Robert Dewitt, “Hunting in Alabama,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, last updated January 25, 2016; accessed April 15, 2018: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1893. ↵

- For more on Lockett’s relationship with Dial, see Paul Arnett, “Passing the Buck: The Educations of Ronald Lockett,” Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016). This exhibition catalogue, which accompanied an exhibition of the same name, is one of the only scholarly resources available on Lockett’s life and work. ↵

- “Although racial attacks occurred in other southern cities, the frequency and number of fire bombings in Birmingham—some fifty between 1947 and 1965—made the city unusually prominent and gave rise to the sobriquet “Bombingham.” Glenn T. Eskew, “’Bombingham”: Black Protest in Postwar Birmingham, Alabama,” The Historian 59, no. 2 (Winter 1997): 371. ↵

- Lonnie Holley, interview with the author, Atlanta, GA, August 2017. ↵

- Lonnie Holley quoted in Mark Binelli, “Lonnie Holley, the Insider’s Outsider,” New York Times, January 23, 2014, accessed March 15, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/26/magazine/lonnie-holley-the-insiders-outsider.html. Holley’s reference to Dr. King’s toilet paper sermon is particularly poignant, given that the Civil Rights leader was assassinated after supporting the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, TN (the “I Am a Man” protest). ↵

- Robin D. G. Kelley, “A Conversation with Robin D. G. Kelley,” Open Space SFMOMA, accessed February 5, 2018, https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2017/05/a-converstion-with-robin-d-g-kelley. ↵

About the Author(s): Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander is Assistant Curator of American Art at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University