Marsden Hartley’s Maine

Curated by: Donna M. Cassidy, Elizabeth Finch, and Randall R. Griffey

Exhibition schedule: The Met Breuer, New York, NY, March 15–June 18, 2017; Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, ME, July 8–November 12, 2017

Exhibition catalogue: Donna M. Cassidy, Elizabeth Finch, Randall R. Griffey, with contributions by Richard Deming, Isabelle Duvernois, Andrew Gelfand, and Rachel Mustalish. Marsden Hartley’s Maine, exh. cat. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017. 184 pp.; 194 color illus. Hardcover $50.00 (ISBN: 9781588396136)

The exhibition opens with a panoramic, wall-size video projection of waves crashing onto the craggy rock formations of coastal Maine. The works of art that follow reveal a continuation of this theme by powerfully evoking a sense of place: sweeping vistas of imposing Mount Katahdin; compressed, intricately textured views of wooded terrain and foliage; dramatic seascapes; austere churches; piles of lumber; burly fishermen; heroic athletes; scantily-clad beachgoers; and a spiny, bright red lobster modeled against a pitch black background (fig. 1). This is Marsden Hartley’s Maine.

Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) was a famously itinerant artist who spent time in Paris and Berlin in the 1910s and traveled to areas as wide-ranging as Mexico, Nova Scotia, and the American Southwest over his four-decade-long career. He is perhaps best known for the early, Berlin-based works, including Portrait of a German Officer (1914; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), in which he cultivated his own brand of abstraction by synthesizing French avant-garde styles and German Expressionism. Although scholars have examined these works and other discrete phases of his career, Marsden Hartley’s Maine is the first exhibition to underscore the fertile and sometimes tenuous relationship the artist had with his home state. It yields new insights into the importance of Maine as a locus for subject matter and as a modernist testing ground. More specifically, it establishes Hartley’s commitment to a regional expression of American modernism.

Arranged chronologically and thematically in eight sections, the exhibition comprises approximately ninety landscapes, portraits, and still lifes, the majority of which are paintings. The first gallery traces Hartley’s early life and career before he traveled abroad, presenting a group of drawings that includes self-portraits and figural studies of local residents, along with canvases depicting the White Mountains at the western juncture of Maine and New Hampshire. These early landscapes are informed by Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Expressionism, examples of which Hartley had encountered through his early training and association with Alfred Stieglitz and his circle in New York, while the “stitch” brushstroke he used in particular derived from the Italian painter Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899), whose work Hartley had seen in the German magazine Jugend. During this period, Hartley also adopted a distinct compositional formula designed to heighten effects of spatial compression: a square format (as opposed to rectilinear) with four horizontal zones consisting of foothills, a body of water, mountains, and sky. Of the group, Hall of the Mountain King (c. 1908–9; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR) is a standout. It pulsates with chromatic intensity, animated by staccato brushwork. The undulating contours of the mountain create the appearance of outward swelling with its monumentality barely contained in the visual field of the canvas, while rock-like clouds, constricted within a thin strip of blue sky, emerge in thick impasto.

The adjoining space includes another selection of landscapes that demonstrates considerable gestural freedom. One pairing—Maine Woods (1908; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) and Winter Chaos, Blizzard (1909; Philadelphia Museum of Art) —is characterized by dense patterning and collapsing space that verges on abstraction. Hartley’s 1917 visit to Ogunquit, a Maine art colony, is also explored. There, he was inspired by American folk art and the German practice of hinterglasmalerei (glass painting). Shown alongside a nineteenth-century American example in The Metropolitan Museum collection, three of Hartley’s rarely exhibited and little studied reverse paintings on glass reveal how folk art was an integral part of a modernist aesthetic. Although not directly related to the representation of Maine, these works provide a fuller, more richly textured understanding of Hartley’s engagement with regional source material.

The third section, “Dark Landscapes,” returns to a series of paintings completed in Maine between 1909 and 1910, charting the formative influence of the American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) on Hartley’s aesthetic. Ryder’s Moonlight Marine (c. 1870–90; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and a posthumous portrait of the artist by Hartley introduce the theme. The landscapes are dark in palette, devoid of people, and emotionally visceral. We learn that Hartley was increasingly depressed during this period (his first solo exhibition at Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery failed to produce sales), which serves to explain the ominous qualities of the works and the emphasis on themes of ruin, atrophy, and decay. Ryder’s influence, it can be seen, extends well beyond this gallery. Ryderesque clouds and abandoned dwellings—analogous to the storm-tossed boats of Ryder’s compositions—recur in Hartley’s work. Ryder also believed that “imagination was better than nature” and inspired Hartley to paint from memory, recalling things seen and remembered as opposed to directly observed. Years later, in Paris, Hartley again drew on this technique and produced the Paysage series in 1924 that revisited the “Dark Landscapes” of 1909 to 1910.

After years intermittently spent in Europe, Mexico, Bermuda, Nova Scotia, Massachusetts, California, and the Southwest, Hartley returned permanently to his home state at the age of sixty, declaring himself the “painter from Maine” in the catalogue for his 1937 exhibition at Stieglitz’s gallery, An American Place. This proclamation was in fact a strategic artistic and financial choice to align himself with Stieglitz and his Americanism and the growing popularity of the Regionalist movement, which reached its apogee in the interwar decades. In the next section, “Becoming the ‘Painter from Maine,’” Regionalism is defined in terms of the “value of rootedness,” suggesting how “identification with one’s native culture was tantamount to cultural significance.”1 Hartley in turn offered painted meditations on specific Maine locales, such as Vinalhaven, Georgetown, Camden Hills, and the Kennebec River. Highlights of this section include Smelt Brook Falls, 1937 (fig. 2): vertical, totemic trees are nestled against autumnal foliage, counterbalanced by the palpable pull of the waterfall, which curves downward, culminating in a pool of frothy water at its base. Robin Hood Cove, Georgetown, Maine (1938; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) features crudely-shaped boulders outlined in thick black, which take on a primordial quality, while lush layers of thick paint create a reflective surface that mirrors the surrounding foliage and pink twilight sky.

The section of the exhibition that follows is “Embodying Maine,” which contains a thrilling group of unconventional portraits that stand out within the adjoining galleries, which contain landscapes almost entirely devoid of people (fig. 3). Here, however, the visitor is confronted by an unabashedly corporeal presence. Hartley’s protagonists are characterized by monumentality, vibrant color, and expressive distortion. The portraits represent hypermasculine and often eroticized male figures ranging from blond- and blue-eyed hunters; lobster fishermen on a dock amid rugged terrain; powerful athletes bathed in a saintly light; and hardy beachgoers immortalized in oils and in a series of accompanying sketches conceived at Old Orchard Beach. With their bold primitivism and iconic format, the figure paintings manifest Hartley’s attraction to heroic, native types that signified the strength and vigor associated with the region.

The next section, appropriately entitled “Signs of Place,” reveals how Maine was Hartley’s muse. Coastal seascapes inspired by Winslow Homer (1836–1910); abandoned churches in the towns of Corea and Head Tide; and logjams, arranged neatly or in disarray with dramatically jutting and abutting forms, take center stage. After turning the corner, one encounters the so-called marine vistas reminiscent of Henri Matisse and André Derain as well as still lifes, or what Hartley deemed sea signatures, of Maine subjects such as lobsters and seashells, followed by more seascapes realized late in his career. The latter verge on the sublime—moody, brooding, and turbulently realized, reflecting Hartley’s fragile state of mind.

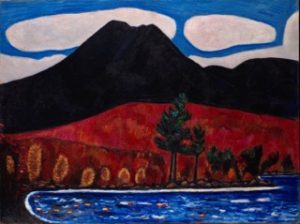

The penultimate gallery centers on nearly a dozen paintings and sketches of Maine’s geological icon, Mount Katahdin (fig. 4). Recalling Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and his Mont Saint-Victoire landscapes, the works reflect Hartley’s interest in seriality and changing atmospheric effects and temporalities. They are preceded by eight prints by the Japanese printmakers Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), whose iterations of Mount Fuji offer a point of comparison. These prints also serve to suggest the larger influence of Japanese art on Hartley’s bold and brilliantly reductive approach to design.

The final section, “Achieving a High Spot,” concludes on a positive note with two canvases—Lobster Fishermen’s Church by the Barrens (private collection) and Sundown by the Ruins (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York)—from 1942. Dspite a career-long trajectory of poverty, and precisely because of his own strategic declaration that he was the “painter from Maine,” Hartley finally achieved recognition and critical acclaim at this time in the form of a new relationship with gallerist Paul Rosenfeld and a promised New York retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition was realized, but not until 1944, one year after the artist’s death at the age of sixty-six.

Marsden Hartley’s Maine ends as it began, except that the projection of crashing waves assumes a different inflection: the works reveal how the geography and topography of Maine offered inspiration over the course of Hartley’s career, and how specific sites and people captured his artistic imagination. Throughout the exhibition, Hartley’s own presence is deeply felt, and understandably so, for a monographic show rooted in place can naturally lead to a biographical focus. The loss of his mother at eight, and his depression, habits of isolation, and peripatetic impulses are explained in terms of his dislocation from Maine. He said to Stieglitz in mid-life, “I want so earnestly a ‘place’ to be.” Hartley’s history of abandonment is poignantly reflected in regional symbols of loss and decay; themes of alienation are conflated with his landscapes and even his self-identification with them; and personal tragedies, such as the deaths of the poet Hart Crane and the Mason brothers, Alty and Donny, are brought to bear on the interpretation of his turbulent, Homeresque seascapes. Even if this intertwined focus on art and life was at times overt, Hartley’s vision was indeed stridently personal, imbued with psychological and emotional drama.

The works themselves are beautifully installed: spare, white walls are a perfect backdrop for the dynamic and richly colored canvases. The wall panels and individual labels are engaging and include thoughtful details that lend important context: conservation discoveries; photographs identifying people and places; mentions of correspondence between Hartley and others, as well as his own essays and poems on Maine. The inclusion of preparatory and finished compositions offers insight into his artistic process, while thought-provoking and visually arresting examples of other nineteenth- and twentieth-century precedents are interspersed throughout as part of the contextualizing mission of The Met Breuer. The inclusion of these works greatly enhances our understanding of Hartley’s art and the varied pictorial strategies upon which he drew over the course of his career.

A rootedness in period context, whether artistic or cultural, emerges as one of the clear strengths of Marsden Hartley’s Maine, although with some limitations. “Embodying Maine” is a case in point. Here, the issue of race is certainly acknowledged although not fully articulated: the wall text describes how the figure paintings in this section manifest Aryan bias, including Hartley’s vision for a “vital Yankee race.” The catalogue essays point to the problematic nature of his affinity for Germany within the context of the Second World War; Hartley’s predilection for “exoticizing the other;” and the history of ethnic and class divisions in his hometown of Lewiston, Maine, a mill town with a large population of immigrants.2 Given Cassidy’s and Griffey’s notable scholarship on race with regard to Hartley, it is surprising that these issues were not more fully addressed.3 Perhaps more attention might have been devoted to Hartley’s own status as a second-generation American and the pressing concerns of those decades as related to whiteness, nativism, and eugenics. Similarly, Hartley’s queerness, previously addressed by Griffey along with Jonathan Weinberg and Bruce Robertson, are only briefly explored in the wall text and catalogue.4

On the other hand, new approaches to Hartley’s oeuvre are certainly evident. Issues related to labor and industry come to the fore; for instance, the early portraits of woodcutters in the first gallery denote active labor, while the heroic workers in “Embodying Maine” are pictured at a standstill, striking a discordant note. Similarly, the series on logjams omit signs of human presence or manual labor but refer to the thriving industries of papermaking, logging, and shipbuilding so central to the Maine economy (fig. 5). Collectively, the works exemplify a seeming contradiction in the approach Hartley assumed toward laboring bodies: some gesture toward productivity and the effects of modernization, while others reflect nostalgia for a bygone past. The emerging importance of ecocritical art history is also alluded to throughout the exhibition, albeit in subtle ways. Hartley sympathized with conservation efforts and lamented the effects of industrialization and tourism (the state was dubbed “Vacationland”) on the Maine landscape. Abundance (1939–40; Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH) depicts an excess of cut lumber in the foreground and a thinned forest in the background; The Ice Hole, Maine (1908; New Orleans Museum of Art) attests to the obsolescence of the ice-harvesting industry; and landscapes featuring abandoned farms run counter to touristic images of Maine and communicate a palpable sense of loss.

An area of renewed focus is the emphasis on spirituality apparent throughout the exhibition. For Hartley, nature was religion: Mount Katahdin was a “sacred pilgrimage,” and the early landscapes reveal what he described as “little visions of the great intangible.” The Transcendentalist ethos of Thoreau, Whitman, and Emerson is a constant presence. The abandoned churches reflect death and decline. The iconicity of portraits was also addressed: one of the early dark landscapes, alternately entitled Resurrection, includes a mysterious, Christ-like figure, while the individuals in Madawaska—Acadian Light-Heavy (1940; Art Institute of Chicago) and Down East Young Blades (1940; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT) appear saintlike. The curators could have taken this one step further by addressing non-traditional religions, such as mysticism, given Hartley’s experience, in 1907, at a retreat for mystics at Green Acre in Eliot, Maine.

The singular contribution of the exhibition is the way in which it highlights the artist’s role within American modernism, while simultaneously complicating that role. Here American modernism meets Regionalism––with Hartley situated at that very intersection. The two, often competing, impulses dominated early twentieth-century American art: one is global and avant-garde in its scope, while the other represents a return to naive realism, provincial subject matter, and social themes connected to a particular place.5 But are the two impulses so fundamentally at odds? Marsden Hartley’s Maine presents them in coterminous ways. Hartley’s cosmopolitanism is often associated with metropolitan urban centers, including New York, Paris, or Berlin. His work, however, can be seen to embody this transnational turn, rooted, as it were, between Maine, Europe, and other parts of the United States. Hartley’s artistic identities as “urban sophisticate” and “painter from Maine” are no longer incongruous but rather go hand in hand.

Although the exhibition positions Hartley within an international context, it also espouses a return to the local. While such an insistent focus on place could risk myopia, the theme actually opens up much broader issues. If anything, further consideration of Hartley’s other meditations on place––whether Dogtown, Provincetown, Nova Scotia, or New Mexico––and how these relate to Maine could have been drawn in more fully in the exhibition and accompanying catalogue. On the whole, however, the exhibition blurs and complicates the often neat distinctions between the local, national, and global. Its redefinition of Hartley’s place within histories of American modernism––and indeed its recasting of Hartley as a Regionalist painter––will definitively shape scholarship on the artist in the years to come.

Cite this article: Margarita Karasoulas, review of Marsden Hartley’s Maine, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3 no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1626.

PDF: Karasoulas, Hartley Review

- As quoted from the gallery wall text for Marsden Hartley’s Maine, March 15–June 18, 2017, The Met Breuer, New York. ↵

- Donna Cassidy et al., Marsden Hartley’s Maine (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 48, 81, 130. ↵

- Donna Cassidy, Marsden Hartley: Race, Region, and Nation (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2005); Randall R. Griffey, “Reconsidering the ‘Soil’: The Stieglitz Circle, the Regionalists, and Cultural Eugenics in the Twenties,” in Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties, ed. Theresa A. Carbone (New York: Skira Rizzoli; Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 2011), 244–77; and Randall R. Griffey, “Marsden Hartley’s Aryanism: Eugenics in a Finnish-Yankee Sauna,” American Art 22, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 64–84. ↵

- Randall R. Griffey, “Encoding the Homoerotic: Marsden Hartley’s Late Figure Paintings,” in Marsden Hartley, ed., Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2003); 207–19; Bruce Robertson, Marsden Hartley (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1995); and Jonathan Weinberg, Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993). ↵

- As Angela Miller has noted, terms including “native” and “cosmopolitan,” and “rooted” and “transatlantic,” have become the standard binary for organizing definitions of American modernism. Angela Miller, “Home and Homeless in Art between the Wars,” in A Companion to American Art, eds. John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill, and Jason David LaFountain (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), 246–63; and Wanda Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). ↵

About the Author(s): Margarita Karasoulas is Assistant Curator of American Art at the Brooklyn Museum and a doctoral candidate in art history at the University of Delaware.