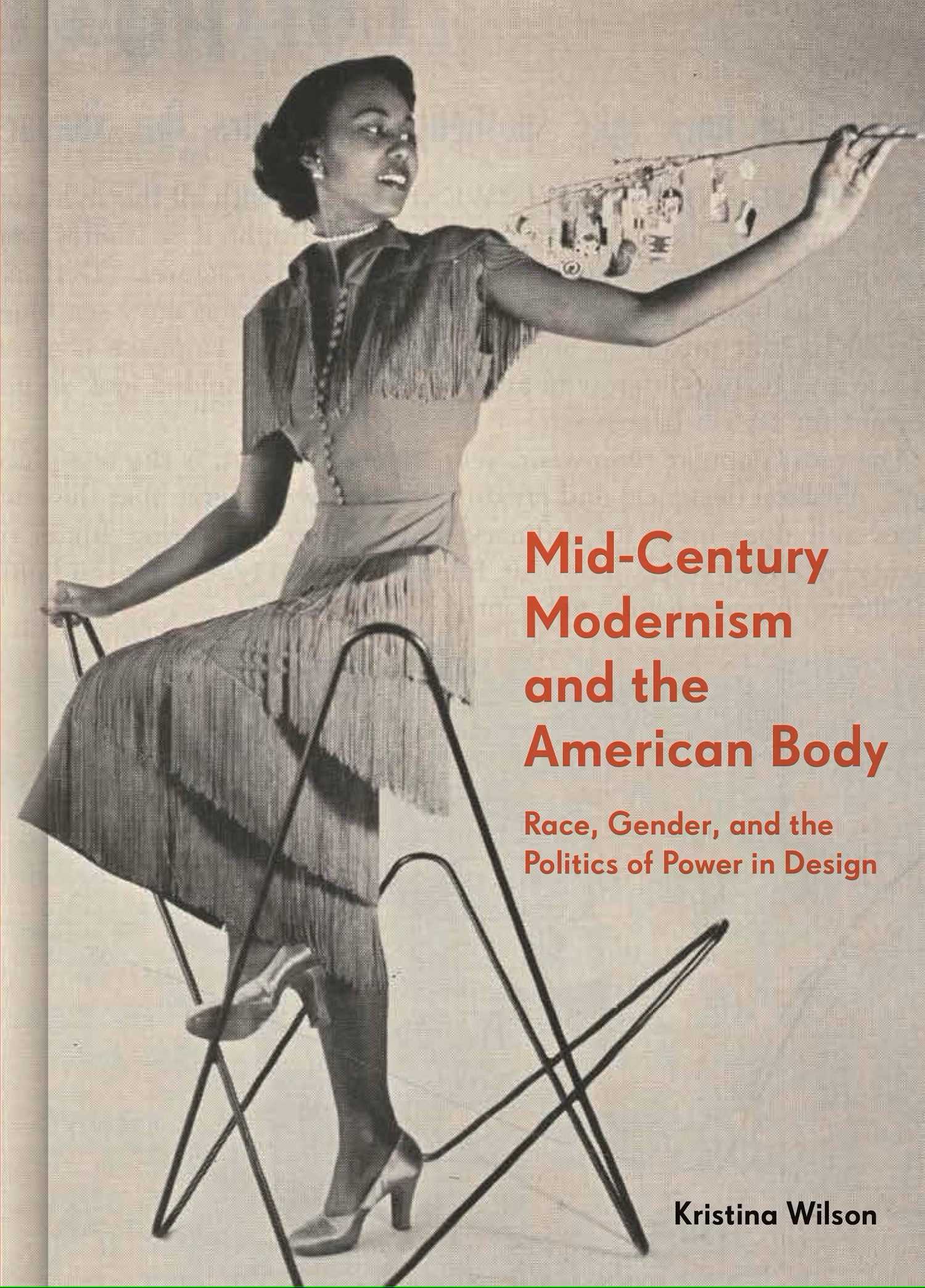

Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design

PDF: Rittner, review of Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body

Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design

by Kristina Wilson

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021. 264 pp.; 74 color illus.; 80 b/w illus. Hardcover: $39.95 (ISBN: 9780691208190)

Early in Kristina Wilson’s nuanced and exciting book Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design, the author draws attention to what she terms “the rhetoric of interior space,” a semiotic framework used to analyze photography and illustrations found in “domestic advice books” published during the late 1940s and early 1950s (30, 21, respectively). What she finds in the images—“no human inhabitants,” “maximiz[ing] the viewer’s sensation of ownership [from a] position of physical superiority,” and “encouraging the viewer to imagine walking unimpeded” through preternaturally orderly rooms—establishes her view of Modernist design “as a force to shape modes of behavior and ways of looking at the world” (18). This shaping becomes wholly apparent in Wilson’s analysis of the artifacts of the mid-century period, namely commercial products, print advertisements, and popular publications, such as Life and Ebony. Her analysis of spaces and the objects contained within, including their dehumanized (literally) otherworldliness, captures what Wilson notices throughout mid-century material and visual culture: the invisible assumptions, inhabitants, labors, and privileges implied in the various expressions of Modernist design.

Importantly, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body is not a new entry into the canon of fealty toward midcentury Modernist design.1 Rather, it is a brilliant analysis of the semiotics of Modernism as conveyed through advertisements, sales brochures, and domestic objects, such as those sold by uber-Modernist retailer Herman Miller. While the term “mid-century” may describe the emergence of the form, Wilson reminds us that popular acceptance of, and even obsession with, Modernist design has well exceeded the bounds of those decades. Her analysis illuminates the ways in which the echoes of the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s remain deeply resonant for both makers and consumers of contemporary design.

The book contextualizes the ethos of the mid-twentieth century in relation to class, gender, and race as articulated by attendant objects of design and architecture. But, importantly, the book is also a critique of our continued obeisance to an aesthetic and consumerist movement, birthed almost a century ago, that privileges the cultural values of upper-middle-class tastemakers while diminishing or entirely ignoring the social inequities—particularly for Black residents and women—that were consistently left invisible outside the frame. Wilson asks us to consider how, why, and in what context we perpetuate the social dogmas of a period that began in the wake of World War II with the emergence of an American middle class, through the calcification of women’s roles vis-à-vis technological household innovations and continuing with the liberatory promises of home-placemaking to Black, Brown, and immigrant families. Of course, this was rarely achievable, as evidenced by decades of overpolicing in these homeowners’ neighborhoods, the often-fatal occurrences of police raids, and the constant threat of displacement caused by gentrification.

In chapter 1, “The Body in Control,” Wilson analyzes four popular “domestic advice manuals” that expounded the virtues of Modernist architecture and design. Wilson reads the text and images in these manuals in relation to gender and race, examining how the authors’ own identities structured their domestic advice. Wilson demonstrates how such manuals positioned the idea of Modernism, including obsessions with cleanliness, neatness, and order, against women and Black homeowners while conveniently rendering invisible the presence of immigrants. The authors of the manuals tell their readers to embrace and enjoy Modernist design or be left behind. The books thus function as instructions on how to live as modern people. Failing to build and maintain a Modernist home, in their view, is not only a failure of design but of character, for only the efficient, lighter, and more graceful Modernist home can counter the cluttered, noisy, foul-smelling, and embarrassing non-Modernist home (56).

Two exceptions to the exclusionary narrative of many midcentury design manuals may be Paul R. Williams’s The Small House of Tomorrow (1945) and New Homes for Today (1946), which Wilson reads as counternarratives to prevailing beliefs in the industry. In particular, Williams’s texts offers Black homeowners “a commitment to promoting the agency of those living within” Modernist homes (65). For Williams (and other authors within the pages of Ebony magazine), Modernism symbolized the freedom to enjoy the ownership of one’s custom-designed home and the luxury of safety by virtue of being identified as modern or aligned with Modernism. Wilson convincingly positions Black Modernism as both a marker of status and, from the perspective of the white gaze, a marker of acceptability.

Chapter 2, “Modern Design? You Bet!,” examines the intersections of gender and race depicted in Life and Ebony magazines during the 1950s, juxtaposing the feature stories, advertisements, and images in each to demonstrate the different priorities symbolized by Modernism for and by each audience. Life, popular with both Black and white readers, depicted Modernism as a symbol of “cleanliness, control, and affordability,” which white consumers could employ “as an accessory for an emerging identity” (70). For readers of Ebony, presumed to be predominantly if not exclusively Black, “Modernism resonated with sociability, bodily comfort, and elite class distinction” (70).

The juxtaposition of images Wilson includes in this section is persuasive. For example, in feature articles, magazine editors created nuanced narratives in support of Modernist ideology. One feature in Life shows Charles Eames standing amid his work: the artist as art object, the man as Modernist icon. For the middle-class white consumer, Modernism may be affordable and efficient, but it is also touched by genius, conferring a status marker on the consumer (74). In a comparative feature in Ebony on the Black Modernist designer Addison Bates, Bates (with his brother) is shown actively working in his shop, appearing more as a laborer than a design icon (74). Similar juxtapositions are rendered in whiskey ads in both magazines, with the same essential iconography at play. In Life, a white male architect perches, statuesquely and presidentially, on a desk for his portrait, while in Ebony, Black architects are positioned among colleagues or clients, either working or seated in social communion (86). For the Black upper-middle-class consumer, the designs are aspirational, but the designers remain working-class laborers (74).

Wilson’s perceptive and persuasive analysis of gendered image making is found throughout the book. Chapter 3, “Like a ‘Girl in a Bikini Suit’ and Other Stories,” illuminates the geometric, verbal, and visual presentation of gendered objects. Women model furniture as extensions of the female form (figs. 26, 102, 103) Men (fig. 105) and even dogs (fig. 91) are served, nurtured, and comforted by the feminine form of the Eames Lounge Chair. The reader should note in this chapter the re-emergence of Wilson’s “rhetoric of interior space” (figs. 97–98) to underscore the primacy of order and object over the life of the home, including the gendered labor involved in maintaining so sublime a picture.

Wilson’s analysis of Modernist design and race further considers how whiteness seeps through the Herman Miller semiotic frame. In the showroom and catalogues, Modernist objects (presented as orderly, mass-produced, and for sale) are situated against the “exotic” objects of non-white societies (which are decorative, whimsical, and other), even as they are offered to consumers as objects for cultural appropriation (148). In the Miller catalogue, the non-Modernist objects offered white consumers a view of ownership of non-Western objects, which are positioned as artifacts of the past.

If I could add another subtitle to Wilson’s final chapter, “The Quick Appraising Glance,” it would certainly center the word fetish. Here the author highlights objects that served to objectify and exoticize Brown and Black bodies but were coded as Modernist and therefore elegant. There is an eerie paradox of orderliness and profligacy in many of the decorative objects shown in this chapter. They express Modernist minimalism, but in the demand for consumption, they speak to excess. How will the Modernist housewife or servant store all of the family’s decorative and functional products while still retaining the uncluttered organization of the ideal Modernist home (121)? At the same time, Steuben crystal, Castleton China, and Stonelain ceramics offer a paradox of aesthetics in that they draw from historical decorative forms and images while explicitly eschewing over-ornamentation as a signifier of the past. Modernist decoration must show itself to be of the future: abstract, minimal, and untethered from cultural heritage unless it features the exotic other (figs. 137–39).

And yet, as Wilson argues, the Black home remained a site of liberatory possibilities where accessories and ornamentation are concerned. Witness in the pages of Ebony the invitation for upper middle-class Black homeowners to invest in African art collections. The exotic non-Western object, purposefully placed in the Miller catalogue as an explicit counterpoint to Modernism and its futurist ambitions, is situated in Ebony as a reclamation of cultural connection in the hands and homes of industrial designer Perry J. Fuller, dancer Pearl Primus, and “wealthy heiress” Sarah Washington Hayes (figs. 149–51).

At the heart of Wilson’s thorough analysis of the semiotics of race and gender in midcentury Modernist visual and material culture is a question of freedom and constraint: the freedom inherent in the imaginations of those who had the privileges of bodily autonomy and accumulation of wealth and the constraint on those for whom Modernist design reified roles of social and cultural submission; the freedom allowing some people dreams of the future and the constraint forcing others to serve as tools of the design performance rather than inhabitants of home spaces. Freedom itself could span the ability to own and consume culture from anywhere and everywhere as a matter of status, as well as the ability to reclaim culture as emblems of both a shared past and a collective future.

Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body contributes a vital counternarrative to the canon and should be essential reading for historians, educators, designers, and students of design. The value of this book is, in part, Wilson’s insightful analysis but also her invitation to look closer. In her analysis and her adept visual literacy, she offers readers an invitation to see, a guide to visual thinking through the lenses of aesthetics and critical social theory. This type of looking is not just about deconstructing the formal properties of the image and imaged but about understanding all that remains invisible around the frame: the people, clutter, noise, odors, labor, as well as the class, gender, and racial inequities that inconvenience the narrative of an egalitarian, Modernist utopia. Through Wilson’s semiotic readings, we are invited to see that order within the frame (figs. 7–9) requires labor outside of it (see Dorcas Hollingsworth, 56–57). Perfection within the frame (figs. 119–20) implies an intolerance for imperfections perceived beyond it (51–52). Every scene of social life that implies an “us” exists concurrently with objects that fetishize the “other” (figs. 106 and 138).

Operating at the intersection of design critique and a critical inquiry on race, class, and gender, Wilson successfully achieves a “corrective to the extensive body of architectural histories that have seen race nowhere” (15). The book is an essential resource for scholars and practitioners of design who care to interrogate the dominant narratives that inform our constructed environments—the messages, products, and architectures that are shaped by the privileged views of powerful culture makers and that shape our collective realities. Certainly, it will encourage readers to look more closely within and around the frames to see where race, gender, and power inform design, both in history and in our contemporary world.

Cite this article: Jennifer Rittner, review of Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design, by Kristina Wilson, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17508.

Notes

- Wilson capitalizes “Modernism” and its variants throughout the text: “In this book, I capitalize ‘Modernism’ and its variants (‘Modern,’ ‘Modernistic,’ etc.) in order to designate Modernism as a specific movement, with loose temporal boundaries, in the worlds of art and design” (10). ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer Rittner is Assistant Professor of Strategic Management and Design, Parsons School of Design.