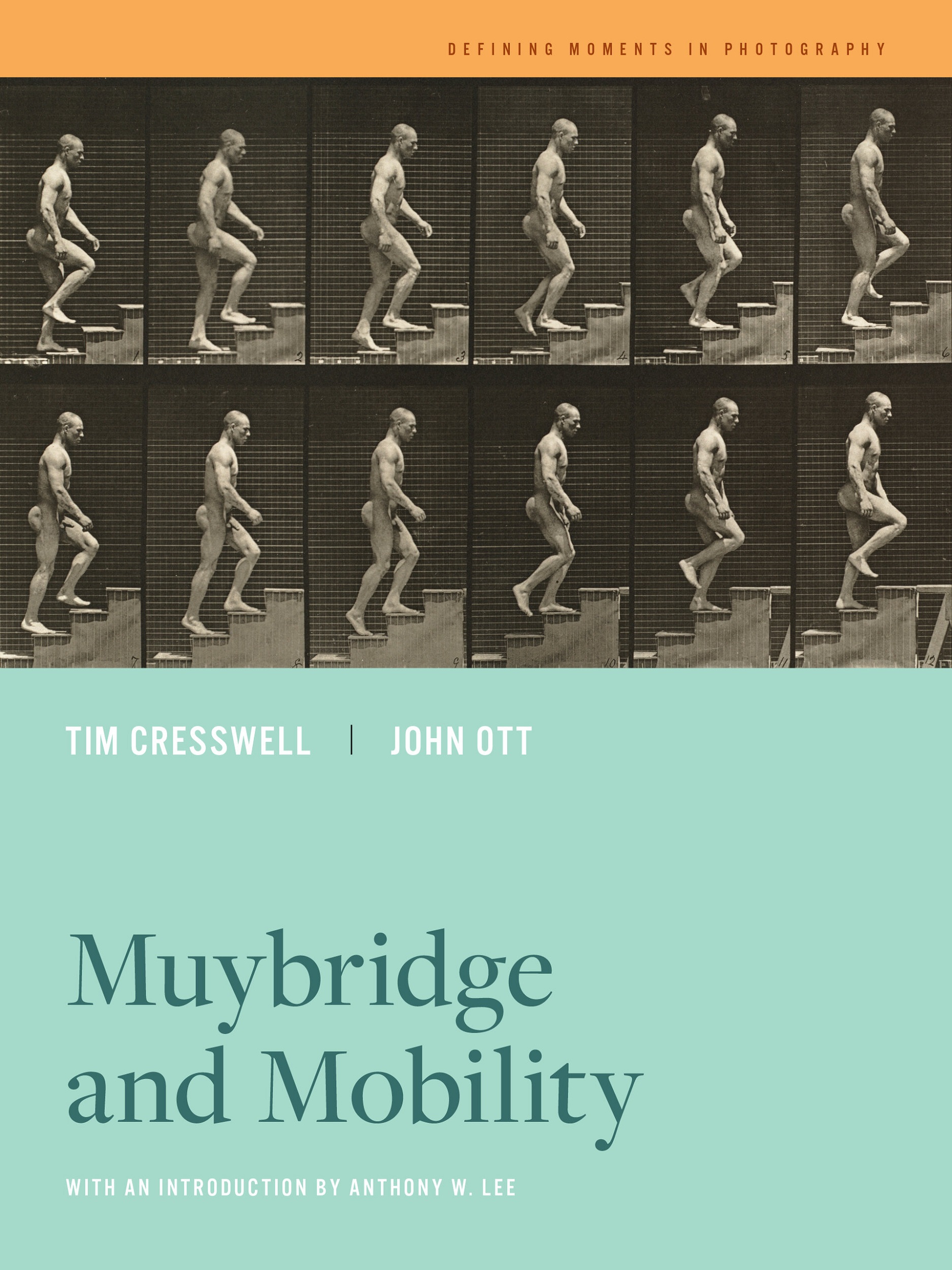

Muybridge and Mobility

PDF: Wall, review of Muybridge and Mobility

Muybridge and Mobility

by Tim Cresswell and John Ott

by Tim Cresswell and John Ott

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022. 144 pp.; 26 color illus.; 8 b/w illus. Paperback: $27.95 (ISBN: 9780520382435)

Muybridge and Mobility is the latest addition to Defining Moments in Photography, the series from University of California Press that provides readers with pairs of essays on a given subject by scholars from wholly distinct academic disciplines. The previous volumes in the series have demonstrated the utility of situating these short pieces in a kind of conversational complementarity, and this latest volume reaffirms both the quality and range evidenced by previous titles. The two essays here, Tim Cresswell’s “Visualizing Mobility” and John Ott’s “Race and Mobility,” each illustrate the usefulness of mobility as an organizing framework for engaging with Eadweard Muybridge’s famous motion studies. Both scholars read Muybridge’s images as part of a network of mobility in its broadest sense, as a discursive formation profoundly connected to all other social and cultural domains. In this way, Muybridge and Mobility is both an excellent example of mobility studies in action and an accessible introduction to the basic structuring concepts of the field.

Still a relatively young academic discipline (if “discipline” is even an appropriate way to think of this concatenation of approaches and fields), mobility studies asserts motion as a ubiquitous aspect of modernity that functions as a key spatial and temporal register of aesthetic and cultural value. It is in this context that Cresswell, befitting his work as a cultural geographer, positions “the ways geographical concepts such as space and mobility play active roles in the constitution of culture and society” (9). For Ott, an art historian, this idea is inscribed upon the bodies of those Black pugilists and riders photographed by Muybridge, imaged bodies that offer “not simply records of Black mobility . . . but mechanisms by which some Black athletes could breach or circumvent barriers of segregation and prejudice” (54). Both understand mobility as a literal and metaphorical embodiment of modernity, symptomatic of the restructuring of consciousness that new technologies both demanded and allowed. Similarly, both authors reveal the ways in which Muybridge was not only recording an emergent modernity but playing an active part in its construction. As Anthony Lee puts it in his brief introduction, with Muybridge’s images, “not just movement but time and space, as they were previously visualized and calculated, were ‘annihilated’” (2).

Cresswell’s key organizing concept is that of the “constellation,” which (following Walter Benjamin’s thinking) he offers as a model for understanding how “individual historical fragments could be related to an encompassing idea” (11). In this way, Muybridge’s horses function as a set of historical fragments that can help us “understand the production of mobilities within wider social and cultural configurations” (21). With mobility central to a lived modernity characterized by radical reconfigurations of time and space, including our movement through them, Muybridge’s selection of the horse is no mere coincidence. As Cresswell makes clear, Muybridge is documenting the dominance of the horse as a feature and function of mobility at the very moment when it is about to fall victim to the machine age. Yet such is the power of the horse as a symbolic entity; it retains its central presence as the key organizing metaphor for the emergent mobilities of machine locomotion. More than this, the motion studies themselves do not merely picture this change but play an active role in constructing these new conditions of modernity: “Muybridge’s photographs of horses thus straddled a fading constellation of mobility and an emerging one. The images were active agents in the process of transformation” (43).

Ott’s recuperation of the Black subjects of Muybridge’s studies reminds us that these images are still alive, still performing their cultural labor no less today than when Muybridge made them. Whether featured in Jordan Peele’s recent film Nope (2022) or, indeed, in this very volume, the images never stop working or moving. They move and shift as we choose to move and shift them, evidence of a kind of lenticularity at the heart of Ott’s analysis. Their mobility reflects and refracts the bodies of those boxers and jockeys who moved (literally, metaphorically, and pictorially) through white Philadelphia, constrained by the image just as that same image simultaneously revealed their unusual (albeit limited) agency as “dynamic actors in their own right, carefully attuned to the promise and perils of publicity” (55). This reading asserts an agency (rooted in the notion of mobility) that more traditional or orthodox ways of understanding the visual image would perhaps overlook. Of course, the Black body is always a body in motion, at labor, in service, constantly moving, working as the mutually constitutive extreme to the privileged ideal of the white body: in repose, utterly self-controlled, and around which other bodies move. We might think of Muybridge’s own still and static body as he observes those Black bodies in motion. This notwithstanding, Ott convincingly argues that Muybridge sometimes privileges the Black body, as in a series of images featuring prizefighter George Bailey, in which the Black boxer is presented in direct opposition to (and lifting much larger and heavier rocks than) his white counterpart. And yet, while such images perhaps allowed Black athletes to “occupy marginal yet productive spaces . . . unavailable to most African Americans,” they also served simultaneously to reinforce their central presence as working, laboring, and moving bodies (102). And so it goes on, the constantly looping, constantly moving contradictions at the heart of the American social and cultural fabric.

It is here that we see the main foci for Cresswell’s and Ott’s essays—the Black body and the horse—cohering, as they perform their critical cultural labor as embodiments of movement and (dis)location. That both the Black body and the horse are present at the very birth of the American moving image should, of course, come as no surprise. In establishing scientific, linguistic, visual, and cultural narratives for itself, white America was (and remains) utterly dependent on the lenticular presence/absence of the Black body. And the drive to order, arrange, and understand the Black body is part and parcel of the same impulse to order and arrange the body of the horse. As Cresswell makes clear, it is the grid, that ever-present backdrop for the measurement of motion, that serves as the central ordering component of Muybridge’s image making. The grid functions as both a feature and organizing principle of modernity—or what Cresswell identifies as a “symptom of a modernist drive to order and linearity” (33). (Rosalind Krauss famously claimed that the function of the grid was to “declare the modernity of modern art,” suggesting that the grid might even be the central metaphor for modernity.1) The key feature of the grid as a symptom of modernity is its seductive (perhaps even hypnotic) appeal to ordering, rationality, and quantifiability. Hence, its aesthetic is intertwined with its assertion of scientific objectivity, another version of the lenticular, moving constantly between science and aesthetics. Cresswell is surely correct when he states, “Art and science came together when Muybridge photographed a horse. His photos linked aesthetic ideals with calculability” (51). This is no less true for those Black athletes that Muybridge chose to photographically grid, submitting them to a world of visual culture already ubiquitously populated by Black bodies consumed by the white gaze as objects of both aesthetic and scientific desire. Following, it makes perfect sense that Muybridge might choose to grid Black bodies along with horses in his motion studies since both are linked to deeper fascinations with the physicality of working bodies, the science of race, the science of breeding, and broader efforts to order and quantify the world.

As both Cresswell and Ott demonstrate in their different ways, the framework of mobility is a way of describing the world and drawing together multiple and disparate networks of engagement. Muybridge’s images, as both individual objects and parts of a greater whole, are both products and producers of their time, reflecting and refracting the broader discourses of power rooted in networks of exclusion, inclusion, and occlusion. The authors each grapple with the complicated relationships between image, space, time, and movement in their problematizing of how the image enacts cultural labor across the fields of geography, art history, and visual studies. Muybridge has always occupied a significant place in the evolution of image making. What Cresswell and Ott underscore in these two short essays is his role in the construction of modernity, as well as his recording of it, by way of showing his studies as living, dynamic entities in motion, “images with agency . . . constitutive elements in the emergence of a new world” (10).

Cite this article: David Wall, review of Muybridge and Mobility, by Tim Cresswell and John Ott, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15357.

Notes

- Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), 1. ↵

About the Author(s): David Wall is Associate Professor at Utah State University.