NANITCH: Early Photographs of British Columbia from the Langmann Collection

Curated by: Helga Pakasaar, Heather Caverhill, and Tania Willard

Exhibition schedule: Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, British Columbia, March 30–June 26, 2016.

Exhibition catalogue: NANITCH: Early Photographs of British Columbia from the Langmann Collection. North Vancouver: Presentation House Gallery, 2016. 95 pp.; 41 color illus. Paperback, $20.00 CAD (ISBN: 9780920293980).

NANITCH bills itself as an exhibition of early photographs of British Columbia, but those of us who study the art and history of the United States in a transnational context will find much of interest when visiting the Presentation House Gallery in North Vancouver. The border separating the United States from Canada was only settled at the 49th parallel by treaty with England in 1846, and the eccentricities of geography led to continuing disputes throughout the nineteenth century. The purchase of Alaska by the United States in 1867, inspired partly by the Russian fear of losing the territory in a war with Britain, led some to briefly imagine the United States extending continuously through British Columbia to this distant northwest region. Canada, however, agreed to Confederation that very same year, and only four years later in 1871, British Columbia was added to the Dominion, quickly dashing any expansionist hopes harbored in the United States. Nonetheless, economic, social, and cultural ties between the two nations remained deep, and indigenous communities living in the Pacific Northwest during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were not consulted when bilateral survey teams brought measuring tools, compasses, and camera equipment to this region in order to map, divide, and allocate the land to the colonizing powers.

“Nanitch” means “to look” in Chinook Jargon, the lingua franca of Pacific Northwest trade during the period covered by this exhibition, from the 1850s to the early 1920s, and the NANITCH exhibition takes seriously the concepts of translation, negotiation, competition, and exchange. Comprised of photographic objects collected by Uno and Dianne Langmann along with their daughter Jeanette, the works on display are just a small selection drawn from some eighteen thousand that the family donated recently to the University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections. Langmann, who owns an art and antique business in Vancouver, began collecting photographs of the Pacific Northwest after arriving in Canada from Denmark in 1955. This type of work could be picked up inexpensively at garage sales and in secondhand stores in those days, and the Langmann Collection is impressive for the range of its holdings, including everything from stereographic daguerreotypes, richly toned albumen prints, glass plate negatives, and hand-colored gelatin silverprints to mass-produced postcards and passport photos. It also contains a number of photograph albums, many of which remain intact, still able to tell the stories imagined by their creators.

The curatorial team for the exhibition, consisting of Helga Pakasaar, curator at Presentation House Gallery; Heather Caverhill, my former MA student at the University of Alberta and currently a PhD student in the Department of Art History, Visual Art & Theory at UBC; and Tania Willard, an artist and curator from the Secwepemc Nation who specializes in the intersections of Aboriginal and other cultures, worked together in a close collaborative manner. Caverhill made an initial selection, and the team then convened to discuss, cull, organize, and develop just some of the thousands of historical narratives possible from such a rich archive of visual material. They agreed to respect the physical materiality of the photographs, refraining from design strategies such as the use of blowups and photomurals that might have enhanced the installation, and brought stories related to colonial practice, such as land exploitation and infrastructure development, Aboriginal life, and the relationship between indigenous peoples and settler colonial newcomers to the forefront. Other stories, related to Chinese and Japanese workers who immigrated to the Pacific Northwest or the diversity of settler colonial experience are hinted at but developed less fully. One engaging family portrait includes two small children dressed in Scottish kilts, while another depicts the members of a brass band in Quatsino on the north end of Vancouver Island, which was settled by Norwegians. Norwegian settlers were lured from North Dakota to this isolated region after reading publicity literature distributed by the Canadian government at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition.

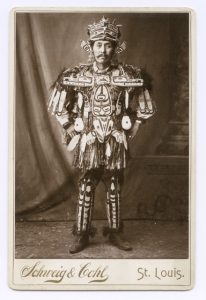

To encourage viewers to look closely at the images selected from this vast collection, the curators have provided minimal textual labeling in the exhibition. Divided into a central entry and two rooms painted bright green and bright blue—green was a color frequently used on the rectangular cards to which stereographic photographs were mounted—the works have been divided roughly into before and after 1900. The photographs are sometimes grouped together by photographer and other times by genre or theme. Along one side and around a corner of the green gallery, a line of nineteenth-century studio portraits by different photographers is placed on a low shelf beneath a wall of framed portrait prints hung parlor style. Hannah Maynard, who opened a photography studio in Victoria in 1862 while her husband was off prospecting, produced some of these images. Most were individually commissioned by city residents, both indigenous and settler, but one is a commercially produced photograph of Bob Harris at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. Such works are important documents for scholars interested in portraiture, performance, and assertions of agency by native performers brought for exhibition at the international world’s expositions.1

Several albums relate specifically to border conflicts between the United States and Canada. One, called Jock Taylor’s Travels and dating c. 1870, includes photographs of the sailors and crew that manned the HMS Zealous, one of the wooden steam battleships selected by Great Britain for conversion to ironclad and sent to the west coast of Canada in 1867. There it served as part of the joint military occupation resulting from hostilities over territorial control of the San Juan Islands. Nicknamed the Pig War after the dispute exploded over the killing of a pig found rooting in the garden of a United States settler, the precise boundary was finally fixed by arbitration in 1872. An album of photographs by Horatio Needham Topley called Views of Alaska documents survey work performed in 1894 by the Canadian Alaska Boundary Commission, which tried unsuccessfully to define the line separating the Alaska Panhandle from British Columbia, left in question due to imprecise treaty language and inaccurate mapping. The 1897–98 Klondike Gold Rush in Yukon led to another round of border disputes in this region, with Canada hoping in vain to receive direct access from the gold fields to the sea. A final resolution was not achieved until 1903.

Visitors at Presentation House Gallery can employ both historical and modern technologies to facilitate their looking at this fascinating history. For example, a vintage “Sweetheart” Stereoscopic Viewer, designed by Alexander Beckers to sit on a tabletop and accommodate two viewers at one time, has been installed in the green room. Reproduction stereo cards from the exhibition have been placed in the rotating rack and the top left open to allow the curious a glimpse into the surprisingly simple mechanism that brought these two-dimensional objects into three-dimensional focus. Tables with computerized touchscreens provide a more contemporary approach. Placed next to actual albums that have been digitized, the computer monitors allow interested viewers to flip through pages that would otherwise not be visible.

Some of the photographs depict culturally sensitive material, for example, children at residential schools and indigenous burial sites. Here the curators chose to disrupt the concept of looking, forcing visitors in the gallery to stop and consider the role of images in the colonizing project. On a shelf with photographs taken at one of the many residential schools established in Canada, as in the United States, to remove native children from their families and violently assimilate them into North American society, a fresh sprig of cedar has been laid beside the images and a translucent sheet of glass placed on top. The images are no longer completely visible, and the children, whose names have not been recorded, are protected from probing and intrusive eyes, provided with a cloak of privacy and a semblance of respect. In another section of the exhibition, a series of stereographic photographs depicting native cemeteries are spread out to overlap each other; only the top edges are visible, and one card has been placed upside down across the others. These are poetic gestures designed to problematize the material on display, stop the viewer from looking, and engage the viewer in a dialogue with and about the past.

Present and future relations between the diverse peoples that inhabit British Columbia, and the Americas more broadly, are also at play in NANITCH. In December 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada completed the first stage of its investigation and response to the horrendous damages wrought by the history of residential schooling, which extended from the 1870s to 1996 in Canada, and delivered ninety-four Calls to Action.2 This exhibition is one of the many that should emerge in response to this document, which demands specific actions on the part of educational and cultural institutions throughout the nation. “Images carry and produce multiple meanings that are not moored to the conscious intentions of those who create or circulate them,” writes catalogue essayist Paige Raibmon. “What politics will these images engage today? What better, truer, and more just stories might they tell if we pay them due attention?”3 By looking at the photographs in NANITCH carefully, thoughtfully, and in consultation with native communities, reconciliation might someday be possible.

NANITCH is accompanied by a handsome paperback catalogue, designed to resemble an album titled San Francisco to BC, which was compiled by an unknown person to incorporate both commercial photographs and personal snapshots of such sites as Mission Dolores and Dupont Street (Chinatown) in San Francisco, the Monterey Peninsula, Yosemite, Portland, Victoria, and the Yukon gold fields. Included in the catalogue are short, thought-provoking essays by Raibmon and Joan M. Schwartz, in addition to texts written by curators Pakasaar, Caverhill, and Willard. Pakassar introduces the Langmann Collection and exhibition concept, Caverhill presents several of the entangled photographic histories she discovered in her extensive study of the archive, and Schwartz explores a single album of photographs by Frederick Dally titled Views in British Columbia, given to John Grant Shepherd upon his departure from Victoria in 1868, that serves as material object, visual narrative, and social space. Both Raibmon and Willard examine the role of indigenous peoples in photographic history, finding compelling evidence that, in Willard’s words, “our ancestors did not lie down: they gathered, negotiated, appealed, attacked, and engaged in exchange.”4 Uno Langmann also provides a brief outline of his history as a collector. Biographies of the principal photographers appear at the end with a concise glossary of photographic processes. Photographic attribution, the authors make clear, is complicated by the widespread practice of buying, selling, or simply appropriating work produced by others when a market existed and money could be made. The UBC Library has digitized a small portion of the collection and made it available online. Both the exhibition and accompanying catalogue are a coproduction of the Presentation House Gallery with the University of British Columbia Library.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1556

PDF: Boone_NANITCH

Notes

- Paige Raibmon, “Theatres of Contact: The Kwakwaka’wakw Meet Colonialism in British Columbia and at the Chicago World’s Fair,” Canadian Historical Review 81, no. 2 (2000): 157–90. See also Randal Rogers, “Colonial Imitation and Racial Insubordination: Photography at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition of 1904,” The History of Photography 32 (Winter 2008): 347–67, and Danika Medak-Saltzman, “Transnational Indigenous Exchange: Rethinking Global Interactions of Indigenous Peoples at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition,” American Quarterly 62 (September 2010): 591–615. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2915), available at http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf. ↵

- Paige Raibmon, “Posing the Past,” in NANITCH: Early Photographs of British Columbia from the Langmann Collection (North Vancouver: Presentation House Gallery, 2016), 58. ↵

- Tania Willard, “Witnessing the Persistence of Light,” in NANITCH, 70. ↵

About the Author(s): M. Elizabeth Boone is Professor of History of Art, Design, and Visual Culture at the University of Alberta