Painful Beauty: Tlingit Women, Beadwork, and the Art of Resilience

PDF: Ariss, review of Painful Beauty

Painful Beauty: Tlingit Women, Beadwork, and the Art of Resilience

Painful Beauty: Tlingit Women, Beadwork, and the Art of Resilience

by Megan A. Smetzer

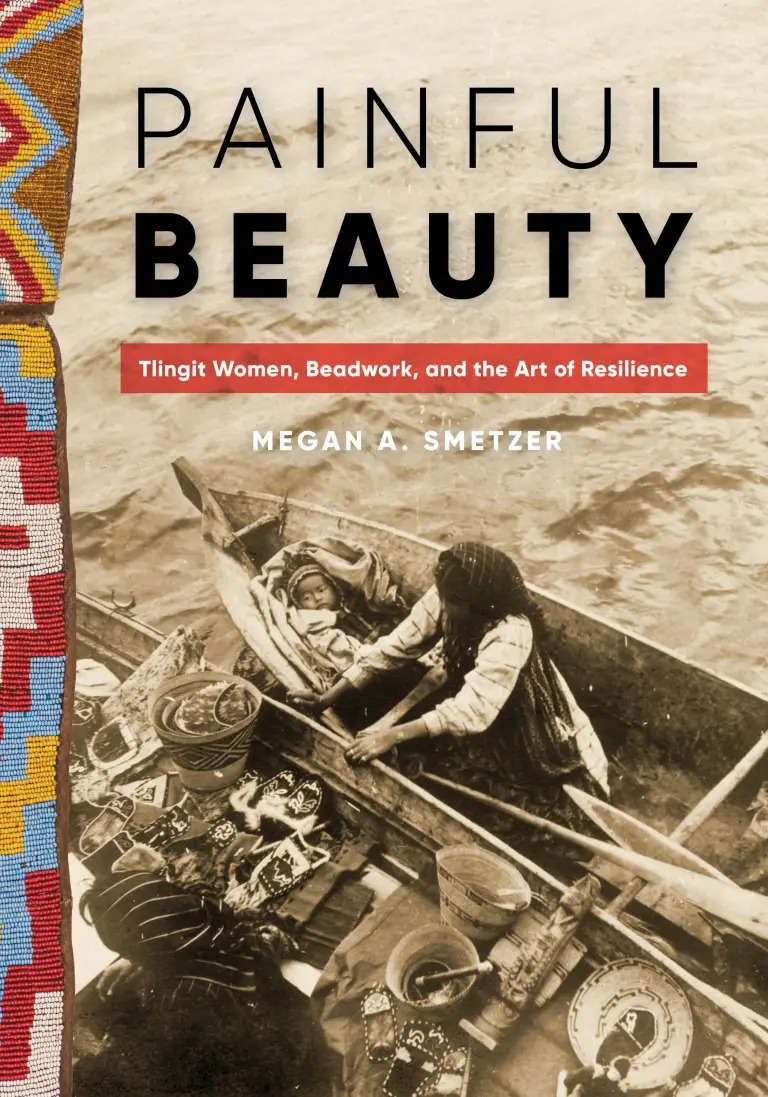

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2021. 240 pp.; 78 color illus.; 15 b/w illus.; 1 map. Hardcover: $39.95 (ISBN: 9780295748948)

Past, present, and future are carefully woven together in Megan Smetzer’s Painful Beauty, a thoughtful and accessible analysis of Tlingit women’s adaptations of beadwork into new forms of cultural production. Foregrounding the experiences of Tlingit women, Smetzer perceptively illuminates their navigations of new materials, markets, and contexts since the nineteenth century. Beads of many materials—copper, bone, stone, and dentalium (shell)—were manufactured and traded by Indigenous peoples for centuries prior to the influx of European trade goods (19–20).

In tracing the history of beadwork’s integration into Tlingit material culture, Smetzer reveals how trade and seed beads moved through new and existing routes as part of the growing fur trade and how the earliest trade in glass beads was incorporated into Tlingit sumptuary systems, which ran along the lines of rank and gender. Throughout Painful Beauty, Smetzer effectively uses oral histories and archival, photographic, and material evidence to demonstrate “how the power and resilience of Tlingit women and their artistic practices have upheld cultural knowledge throughout the complex history and continued ramifications of settler colonialism in Southeast Alaska and beyond” (8). Further, Smetzer’s analysis exposes art-historical and museological structures of thought that conceive of customary (traditional) practices as inherently situated in the past, rather than as dynamic and future-oriented processes aimed at cultural continuity. Painful Beauty works to unseat this repressive norm and the discourses of authenticity that have omitted a wide array of Indigenous customary cultural production from the field of art history.

At the heart of Smetzer’s inquiry are nineteenth- and twentieth-century Tlingit beaded items located in museum collections: primarily moccasins, dance collars, tunics, hats, and the iconic octopus bag. This style of beaded bag resembles the body and tentacles of an octopus, a creature respected as a powerful being, and was incorporated into Tlingit regalia in the nineteenth century (76–77). Rather than simply document the historical items she discusses, Smetzer weaves into her narrative several creative interventions enacted by contemporary Indigenous artists working with museum collections. As a result, the beaded artworks escape seclusion in the museum storeroom and are reactivated in networks of ongoing family relationships. Smetzer’s close studies of the contemporary artists’ interventions, in later chapters in particular, provide a clear and coconstructed analysis that counters the stasis in which customary Indigenous artworks have been held by the dominant discourse. Smetzer’s substantive acknowledgments to these living artists are testament to her collaborative research practice.

Painful Beauty begins with a conscientious examination of how Tlingit women embedded Tlingit values in their beaded artworks. The title telegraphs the intensity and forms of labor enmeshed in beadwork and connects these intricately embellished items to tangible and intangible aspects of Tlingit culture and knowledge (vii). The introduction, “Innovating Adornment,” outlines organizing principles in Tlingit society, including the core values of Haa Aaní (Honoring and Utilizing Our Land), Haa Latseen (Strengthening of Body, Mind, and Spirit), Haa Shuká (Honoring our Ancestors and Future Generations), and Wooch Yáx (Maintaining Social and Spiritual Balance) (18–19). These values frame the analysis of artworks and artists’ practices, and attributional narratives connect the images and collected items with the people and places in which they came into being.

Smetzer imbues a narrative quality throughout the text, beginning with her initial analyses of two works by each of the contemporary artists Allison Bremner and Shgen Doo Tan George that were made in response, respectively, to a nineteenth-century octopus bag and a Chilkat tunic in the collection of the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle. These four works together serve as an entry point to understanding intertwined histories of trade, collection, colonialism, tourism, and continuous practices of Tlingit textile production (3–7). Smetzer addresses how beadwork was jointly shaped by Tlingit peoples and newcomers, and she examines the ways that the dominant scholarly discourses have been formed primarily by Euro-American values, gendered expectations, and categorizations of art and craft. The role of these discourses in determining what scholars and collectors have and have not focused on is made apparent through Smetzer’s meticulous research and documentation. Grounded in Indigenous theories, Smetzer emphasizes concepts of resilience, balance (gender parity), duality, and authenticity to reframe the social and cultural value of Tlingit beadwork. Painful Beauty sheds new light on previously undervalued forms of cultural practice, making a significant contribution to existing scholarship.

For instance, the photographs in Painful Beauty are shared to visualize the people and the collected items that are the focus of the book. This is not unusual. However, by incorporating Jolene Rickard’s and Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie’s thinking on visual sovereignty, Smetzer recasts Tlingit women’s uses of photography as a form of self-representation and identification on their own terms, adding nuanced layers to what they choose to make visible (9–10). This concept is brought to life in chapter 1, “‘They Are Both Plain and Fancy’: Souvenirs and Status within the Alaska Tourist Trade,” in which Smetzer analyzes the historical figure of Gadji’nt, a high-ranking Tlingit woman who used photographic portraits to build her reputation as an artist and trader in growing tourist and settler markets in Alaska (58–61). Through such examples of agency, the valued balance of respect and power between Tlingit women and men becomes visible both in and through the photographs.

Photography plays an equally important role in chapter 2, “Regalia and Resilience: Beadwork at the 1904 ‘Last Potlatch,’” which powerfully demonstrates the ways Tlingit people strategically compromised some customary ways of life in an effort to retain others. Here, Smetzer uses photographs to reveal the role of beadwork in the ancient social and ceremonial practice of potlatch. Comprehensive descriptions of beaded dance collars, tunics, and leggings clearly demonstrate how makers transferred and retained the meanings of existing symbols and colors into these garments while the “selective adoption” of Russian and Euro-American design elements into regalia also generated new symbols for some families and clans (79).

Smetzer’s engagement with community knowledge counters colonial readings of archival texts and images, allowing us to see how such material transformations were misread by Christian missionaries and settlers as signs of acculturation (positive in their assimilationist perspectives at the time) and simultaneously judged as inauthentic by anthropologists and ethnographers (assumed as a negative based on the binary notions of cultural purity and contamination). These new forms, then, paradoxically elided the Christian and assimilationist concerns connected to earlier forms, symbols, and materials while continuing to carry meaning for Tlingit communities (66, 94). Smetzer’s rereading of these items, archives, and images within Tlingit value systems supports the reassertion and enlivening of Tlingit worldviews.

Chapter 3, “Co-opting the Cooperative: Making Moccasins in the Mid-20th Century,” champions the need to “reframe” the discourses that positioned beadwork as inauthentic and that cemented a gendered hierarchy of Northwest Coast Indigenous art (11–12). The preoccupation of the Alaska Native Arts and Crafts Cooperative (ANAC), Indian Affairs, and the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (IACB) with “genuineness” in the mid-twentieth century shaped the market and public perceptions of Indigenous art forms (114–18). These governing bodies operated on the dual premises of protecting Indigenous makers while enforcing externally determined regulations on their production, such as what constituted “authentic” materials, and setting standards based on a European aesthetic (106). Consistent with her focus on the underrepresentation of Tlingit women’s cultural production, Smetzer accurately observes how the structure of IACB catalogues privileged the work of male carvers at the front of each catalogue, even though the market data clearly favored the greater production and higher sales of beaded items made by women (105–7).

This chapter also highlights how the market-driven production of beadwork allowed social and cultural skills to be passed down while the income they generated enabled some women to access education beyond the inferior segregated schools set up by the government, both for themselves and their children (109, 113). Operating with this duality of knowledge systems and values made Tlingit women’s relationships with such organizations complex (42, 53, 94). Changes observed in sewn and beaded dolls made for tourist markets highlight shifting representations of Tlingit communities by Tlingit women. Smetzer’s examination of these dolls demonstrates that critical thinking and strategic negotiations regarding representation and self-representation are not new to Tlingit women’s art-making practices (118–23).

Chapter 4, “Gifts from Their Grandmothers: Contemporary Artists and Beaded Legacies,” traces knowledge-sharing activities across generations of makers, linking narratives and contexts from earlier chapters. A family lineage is apparent in octopus-bag dresses created by Lily Hope, daughter of the late Clarissa Rizal, whose own mother and grandmother had previously produced moccasins sold through ANAC (152–53). Hope’s dresses also contain knowledge that care for and protect the wearer, just as Naaxein robes and other forms of regalia have done for centuries (155). Likewise, Shgen Doon Tan George’s artwork and teaching sustain the four core Tlingit values (145–46). Hope, George, and other artists that Smetzer amplifies here continue to integrate Indigenous values into new versions of customary forms. Their words and work reiterate the embrace of these new materials by their great-great-grandmothers at a time when other modes of expressing identity, belonging, and knowledge were violently disrupted. Future-oriented, Smetzer’s writing elucidates the layered values and ongoing agency of textiles, woven media, and beaded regalia in Tlingit society (156).

In the epilogue, “Beading Beyond Borders,” Smetzer re-presents the breadth and depth of Indigenous beadwork practices and their roles as forms of intergenerational knowledge, history, critique, and memory. In this summative portion of the text, Smetzer situates Tlingit beadwork within the wider context of settler-colonial assimilationism across Turtle Island. Although the period of the early 1800s to the present may appear to be a broad time frame to cover in one book, Smetzer successfully integrates the ways in which trade, settlement, state formation, legislation, Christianity, and Western education were encountered, negotiated, and resisted by Tlingit women. The epilogue pertains to the broadening of the connections and encounters of contemporary Indigenous women artists with the artworks of their ancestors, opening space for further research. Smetzer’s interlaced analyses of collections, photographs, contemporary artworks, and archival materials situate beadwork as a vital and visual marker of Tlingit women’s knowledge and resilience and provides a valuable contribution to understanding how Indigenous women are and have been at the forefront of transforming, transmitting, and sustaining customary knowledge and practices into their futures.

Cite this article: Alison Ariss, review of Painful Beauty: Tlingit Women, Beadwork, and the Art of Resilience, by Megan A. Smetzer, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15213.

About the Author(s): Alison Ariss is a PhD candidate in Art History, Visual Art and Theory at the University of British Columbia.