Psychedelic Patriotism: Peter Max Sparks a Debate on Modern Representations of America

PDF: McKinney, Psychedelic Patriotism

In spring 1976, the federal government was poised to launch a bold initiative to greet international visitors at the nation’s borders in conjunction with the commemoration of the US bicentennial. The General Services Administration (GSA) planned to install a series of billboards as “Welcome to the United States” signs at all border-crossing stations that featured one of seven vignettes illustrating an aspect of the American experience created by the Pop artist and graphic designer Peter Max in his distinctive psychedelic style. Conceived by GSA administrator Arthur Sampson, the billboard project was meant to give the federal government a “fresh, modern image” as part of the Nixon-era Federal Design Improvement Program (FDIP).1

In the decade preceding the commission, Max had mainstreamed psychedelic art through his creation of posters, consumer products, and advertising campaigns. His earlier involvement with the Beats as a designer of album covers for jazz artists had given him access to the youth movement and countercultures, and he segued to psychedelic art in the 1960s as a “hip capitalist” who transformed publicity posters that emulated the concert experience into advertisements that made goods and manufacturers seem cool.2 His commercial work became instant collector’s items and blurred the distinction between advertising and art.

Despite Max’s popularity, the billboards and the GSA’s plans for modernizing the federal image were stymied by political upheaval that began with Richard Nixon’s resignation as president and was fueled by the conservative insurgency within the Republican Party. A national controversy over the project began when Customs Commissioner Vernon Acree, whose personnel staffed the border entry stations alongside Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) agents, halted the installation of the billboards in April 1976, citing psychedelic art’s association with and promotion of illicit drugs. This move initiated a dispute between Customs and the GSA that would span three presidential administrations.

Both agencies took the dispute to the public, arguing for and against modern art’s ability to embody American ideals. The GSA asserted that Max’s work was prevalent in virtually every aspect of American life and popular culture, claiming it illustrated how timeless national ideals were expressed in a modern vernacular. The Customs Service dismissed the GSA’s justification as too intellectual and stated that the GSA did not take into consideration that psychedelic art embodied the lawless and hedonistic lifestyle of the illicit drug culture that stood in direct opposition to the federal government’s War on Drugs.3

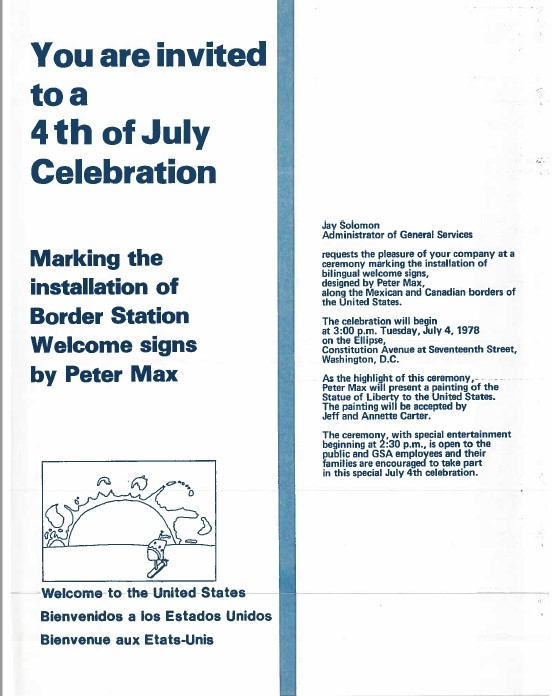

The impasse was broken when Jimmy Carter personally intervened and had the signs installed and dedicated on July 4, 1978 (fig. 1). This resolution lasted only as long as his presidency, and when Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter in 1981, the Customs Service campaigned for the billboards’ removal. A compromise was reached between the Customs Service and the GSA that removed the signs when they showed evidence of wear and tear.

The controversy over the Max billboards could be dismissed as a forgotten historical anecdote in the cultural wars of the last half of the twentieth century but for the involvement of federal agencies and President Carter in mediating the debate. By outlining the machinations of advocacy and opposition among government agencies and across presidential administrations, this article traces how different factions crafted characterizations of modern art to polarize the opinions of the public and how these arguments became aligned with party politics and formed the basis for national arts and humanities policies. This article also examines the trajectory of Max’s career amid the ongoing debate over public art in the United States.

The Bicentennial and the Americanization of Modern Art

The billboard controversy reflects social fragmentation among generations, economic classes, and ethnicities during the twentieth century. Exacerbated by the debates over the Vietnam War and civil and economic rights movements, these divisions became polarized as the nation approached its bicentennial. Failures in planning and charges of corruption forced the beleaguered Nixon administration to abandon its plans to celebrate the nation’s future and reorganize the commemoration in 1974 under the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration (ARBA). ARBA changed the focus away from a national celebration to identifying and endorsing local activities that, according to the New York Times, gave groups from the Boys Scouts of America to the Ku Klux Klan roles in planning the commemoration.4

Communities of color responded to the bicentennial with ambivalence, resignation, or disdain. A syndicate of African American newspapers asked, “What is there to celebrate?”5 In contrast, white ethnic groups asserted their place in the nation’s historical narrative by providing a nostalgic portrayal of their individual group’s heritage.6 For example, the Swedish American Bicentennial Council reaffirmed its allegiance to God and country, citing its purpose to “recall our history and increase awareness of the contributions of Swedish immigrants and their descendants.”7

Ethnicity, nostalgia, and heritage became the focus of bicentennial-themed exhibitions and led to debate over how American art should be evaluated.8 Swedish immigration was celebrated by Dream of America, which was circulated nationally by the Smithsonian Institution’s Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES). Art historian Barbara Groseclose’s 1976 exhibition at the National Collection of Fine Arts of the German immigrant Emanuel Leutze, painter of Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851; Metropolitan Museum of Art), sought to counter his reputation as a “Pollyanna painter” and praised his ability to convey nationalistic themes in mythic proportions.9 The art critic Hilton Kramer summarized the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s World of Jefferson and Franklin exhibition—which mixed artifacts, paintings by Thomas Cole and Albert Bierstadt, and a stuffed bison—as “an elaborate and expensive exercise in nostalgia, rich in picturesque effects but devoid of anything resembling a serious idea.”10 Kramer, along with arts reporter Grace Glueck, criticized the landmark exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art, curated by artist and scholar David Driskell, as “merely” social and ethnic history.11 Art historian Christin Mamiya further traces the pervasiveness of this trend during the bicentennial by attributing the popular reception of the 1976 retrospective of Robert Rauschenberg to figurative representations that imbue his work with historical resonance.12

While both traditional and modern-leaning art critics acknowledged the change in valuation in exhibitions during the bicentennial, they disagreed about its benefit. The conservative New York Times critic John Canaday saw the celebration of nationalistic themes as heralding the “Americanization of modern art.” To this end, he applauded art museums for returning to figurative art styles, like Photorealism, and mounting blockbuster exhibitions that appealed to the public instead of showcasing nonrepresentational works favored by the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) and a coterie of privileged patrons and intellectuals.13 His point of view was shared by John Russell, who praised the National Gallery of Art’s Eye of Jefferson exhibition for exalting and entertaining the public while mocking Cubism’s inability to convey national themes.14 Kramer condemned this trend as introducing “extra artistic standards” that emphasized cultural relevance over artistic merit.15

Conflicting points of view also sparked controversies related to public art, and Glueck and cultural historian Michael Kammen see them, in part, as a class struggle between a public that favored figurative art and the art establishment that championed abstract works.16 The sociologist Steven Dubin places art controversies within a societal context and notes they are most likely to occur “when prolonged struggles have fractured the community, when distinct social changes have left individuals estranged . . . as civic spirit becomes deflated by weariness and despair, and alienation replaces a sense of common cause.”17 Embedded in the public art controversies of the 1970s and in the planning for the bicentennial was the question of whether the nation should seek inspiration in the nostalgia-laced past or in the promise of the future.

On entering office in 1969, Nixon presented a forward-looking philosophy he dubbed the “new spirit of ’76,” which the New York Times described as a thinly disguised effort to turn the bicentennial into a celebration of his own presidency.18 The Nixon era would establish Republicans as the majority party by securing voters who had ceased to see the Democrats’ initiatives as beneficial and now viewed them as an uncaring bureaucracy.19 Groups within this new coalition held disparate political philosophies, so Nixon pacified factions with the introduction of revenue sharing and block grants to the states that decentralized but maintained social programs supported by moderates while offering conservatives a means to reduce federal bureaucracy. He called these changes the “New Federalism” and sought the assistance of the arts community to sell them to the public by modernizing the image of the government.20

Art and the Promotion of the New Federalism

To present the New Federalism as a sea change in the executive branch, the administration employed the advertising strategies from the 1968 presidential campaign that had marketed Nixon like “corporations sold soap.”21 The administration also needed to mask its activities and give the appearance of impartiality, so Nixon tasked Nelson Rockefeller’s former aide and incoming chair of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), Nancy Hanks, to remake the federal government’s image through FDIP.22 Nixon also noted that the NEA’s relationship with states’ arts councils was a model for the New Federalism that “accords with the administration’s policy of stimulating state action through Federal incentive.”23

Foremost, he found that Hanks could build his personal standing in the arts community, and Hanks embraced this role to make the NEA into the fountainhead of federal arts policy. She employed her ties with the Rockefeller family and the National Business Committee for the Arts, as well as her former position as president of the Associated Councils for the Arts, to convince both the New York establishment and grassroots organizations that Nixon was the “kind of friend we need.”24 The New York Times Magazine chronicled her efforts and the change in Nixon’s reputation across the arts community by naming him the “man who’s made the most solid contribution to the arts of any President since FDR” in a 1971 headline.25

Nixon rewarded Hanks with the authority to act across the federal government, and he directed every federal department and agency to determine how the arts could be employed to further their missions and report their findings to Hanks.26 Hanks then engaged the national arts community in FDIP. She convened the first Federal Design Assembly in 1973 to revamp every aspect of government design, from logos, publications, and graphics to public buildings, landscaping, and art installations.

She established a task force to develop an action plan that was headed by National Gallery of Art director J. Carter Brown.27 It included Arthur Sampson, a Nixon loyalist and Republican operative from the party’s moderate wing, because he was principally responsible for the architectural and administrative services that coordinated federal design.28 Sampson began his career as a financial and manufacturing manager for General Electric before moving into the Pennsylvania state cabinet under governors William Scranton and Raymond Shafer. Both remained patrons, and with Republican Senate leader Hugh Scott, they secured successive GSA positions for Sampson until his elevation to GSA administrator in 1973.29

Sampson had a national reputation as a maverick and a reformer. The Engineering News Record attributed Sampson’s accomplishments to a “combination of supersalesmanship, personal flamboyance, [and] modern management.”30 The architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable praised him as an “enlightened individual” who provided hope that government design could be “lifted out of the federal sludge.”31

Sampson established a formal partnership with the NEA to reinstitute the GSA’s troubled Art in Architecture (AiA) program, which set aside a percentage of a building’s construction budget for art. The public’s misgivings about the government’s support of abstract art, opposition in Congress, and concerns about costs had led the Johnson administration to discontinue the program in 1966.32 Sampson sought Hanks’s assistance to defuse congressional criticism.33 Her one-on-one lobbying was credited with changing the votes of one hundred members of Congress in support of an expanded NEA budget, and she lobbied for AiA as an extension of the NEA’s work in placing art into communities.34

The first commission under Sampson, Alexander Calder’s Flamingo (fig. 2), was a politically astute choice that announced the rebirth of the AiA and united the art, civic, and business communities in support of the program. Calder’s relationship with corporate leaders, like Nixon stalwart and Pepsi Cola executive Donald Kendall, buttressed national support for the commission.35 Another Calder commission had changed the position of then–Republican house leader Gerald Ford on public funding for the arts. His hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan, had prevailed on him to secure a NEA grant to procure Calder’s La Grande Vitesse, resulting in Ford’s support for the NEA and his recognition of the transformational qualities of modern art. He told his colleagues that “a Calder in the center of the city, in an urban development area, has really helped to regenerate a city.”36

Similarly, the installation of Calder’s Flamingo at the Federal Center in Chicago was intended to rehabilitate the staid and stodgy reputation of the federal government. Fifty-three feet in height and vermilion in color, the steel sculpture introduced an element of whimsy, enticing people to visit the federal complex. The day of its unveiling on October 25, 1974, was proclaimed “Alexander the Great Day” and began with a circus-like parade to the first of two ceremonies. Mayor Richard Daley stated that the sculpture had transformed Chicago’s Loop “into the largest outdoor museum in the world.” Sampson followed with a statement from now-President Ford calling the sculpture “a milestone in the federal government’s effort to create a better environment.”37 Then the parade continued to the Sears Tower, where Calder’s Universe was unveiled, underscoring the parallel between the federal government and the retail behemoth in reinventing urban areas and work environments through art.

The positive public reception of the Calder installations led the GSA to continue the Nixon-era plan to employ modern art to promote the bicentennial as the start of a new era. On July 4, 1972, Nixon had addressed the nation outlining a tripartite approach to the commemoration: Heritage ’76 focused on the founding of the nation, while Horizons ’76 looked to the nation’s third century, and Festival ’76 encouraged international tourism.38 Sampson had become acting GSA administrator a month earlier and had immediately moved the Bicentennial Coordination Center under his direct control.

To coincide with Philadelphia’s bicentennial commemoration, the AiA installed Louise Nevelson’s Bicentennial Dawn (fig. 3) in the new James A. Byrne Courthouse, located within a short walk to Independence National Park and the Liberty Bell. The installation, comprised of twenty-nine patterned wooden columns divided among three bases, was described by the sculptor as occupying the space between past and present. Sampson’s remarks at the unveiling of its maquette on September 12, 1975, explained the sculpture’s relationship to the bicentennial by invoking the Horizons ’76 and Festival ’76 themes. He presented Nevelson’s work as “a glimpse into the future for the millions of tourists who will visit Philadelphia during the bicentennial.”39 Also in his comments and those related to other installations, Sampson presented the AiA’s commission as the start of a new era in public art, with fifty-one projects being undertaken by the GSA across the nation.

Psychedelic Art for Political Purpose

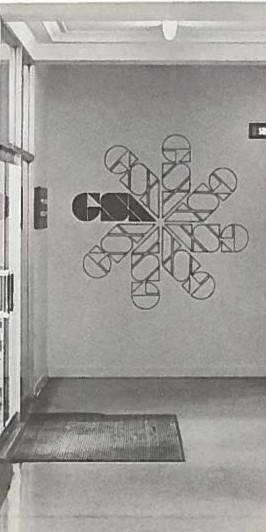

The use of modern art for political benefit by the Nixon administration encompassed the contemporary psychedelic art style. This new era in federally funded public art also heralded an overhaul of the GSA that Sampson intended as a model for a larger rollout affecting the entire government in the bicentennial year. The 1974 unveiling of the new GSA on its twenty-fifth anniversary marked the end of a bureaucracy created by a Democratic president and the creation of the “business arm” of the federal government. Sampson outlined his plan in the report titled A New Way, which included a public relations component that employed modern art to eradicate the public perception of the federal government as “distant, arbitrary, impregnable.”40 He based his plan on corporations such as Chase Manhattan that were modernizing their images by redesigning their graphics and advertising, as well as displaying modern, abstract art in their offices to inspire personnel to think and work differently. As visual culture historian Alex Taylor outlines, David Rockefeller used Chase’s art program to eradicate the bank’s stodgy image and to create a new marketing campaign based on abstract art. The Chase logo, consisting of a square encased in an octagon, was presented as the “new symbol of service.”41 The logo’s power over perception was lauded in 1969 by the psychologist Rudolf Arnheim, whose research on perception was funded in part by a Rockefeller grant. Arnheim distinguished the logo among those of other national corporations as a “modern trademark” that embodied “the necessary vitality and goal-direction.”42

The GSA pursued the same goal in its logo redesign executed by Peter Masters, its resident graphic designer, who had attended the Central School of Art and Design in London, the Parsons School of Design, and Yale University.43 Masters provided a decided contrast to the official seal of the agency by reducing the letters of GSA to a stencil and repeating them in a circular pattern until the letters were abstracted into amorphous shapes (fig. 4). He recalls the “cut up” method of design used by writers and psychedelic artists to transform printed words into visual poetry by placing words or images together in what appear to be random patterns.

The ability of the “cut up” method to disrupt established thought processes and change the perceptions of individuals had been outlined by former Harvard researcher and psychedelic guru Timothy Leary in the Psychedelic Review, a journal for which Max had served as an art consultant.44 Repeating elements in a circular pattern was also a characteristic of Max’s work from the 1960s. Max was involved in GSA’s image redesign as a member of the FDIP graphic review panel and was also working concurrently with Masters on the billboard commission.45

The integration of elements of psychedelic art in the GSA image redesign followed precedents set by corporations and the 1968 Nixon campaign. A study by cultural and political analyst Thomas Frank explains: “American business . . . imagined the counterculture not as an enemy to be undermined or a threat to consumer culture, but as a hopeful sign, as symbolic in their own struggles against the mountains of dead weight procedure and hierarchy that had accumulated over the years.”46

A 1968 Merchandising Week editorial observed that “our media push psychedelics with all its clothing fads, [and] so-called way out ideas [to transform] the buying habits of some older more affluent customers.”47 Even the Christian evangelist and Nixon’s spiritual counselor Billy Graham adapted psychedelic lingo and catch phrases associated with the drug LSD. He turned Leary’s slogan “Turn on, tune in, and drop out” into “Turn on Christ, tune into the Bible, and dropout of sin.”48

The world’s largest advertising firm, the J. Walter Thompson Company (JWT), incorporated this trend in what the firm called “The New Creativity,” an initiative that employed the idiom of youth culture in advertising campaigns. JWT also lent staff to the White House, and three former executives became Nixon’s senior aides, including chief of staff H. R. Haldeman, who had engaged the psychedelic poster artist Wes Wilson to decorate the JWT office in Los Angeles.49 Ronald Ziegler, who had managed the Disney and 7Up accounts for JWT, became press secretary.

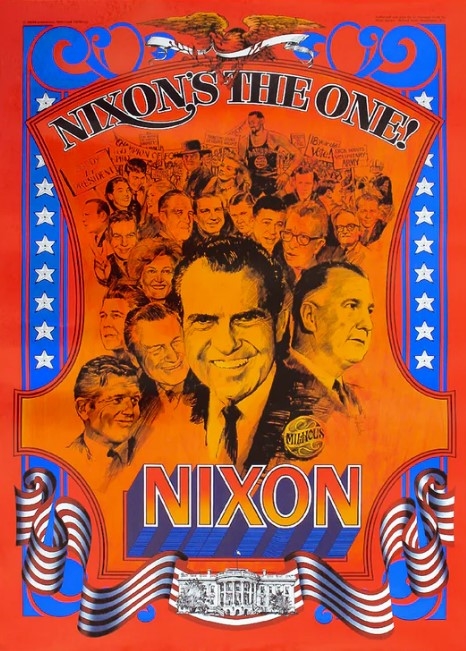

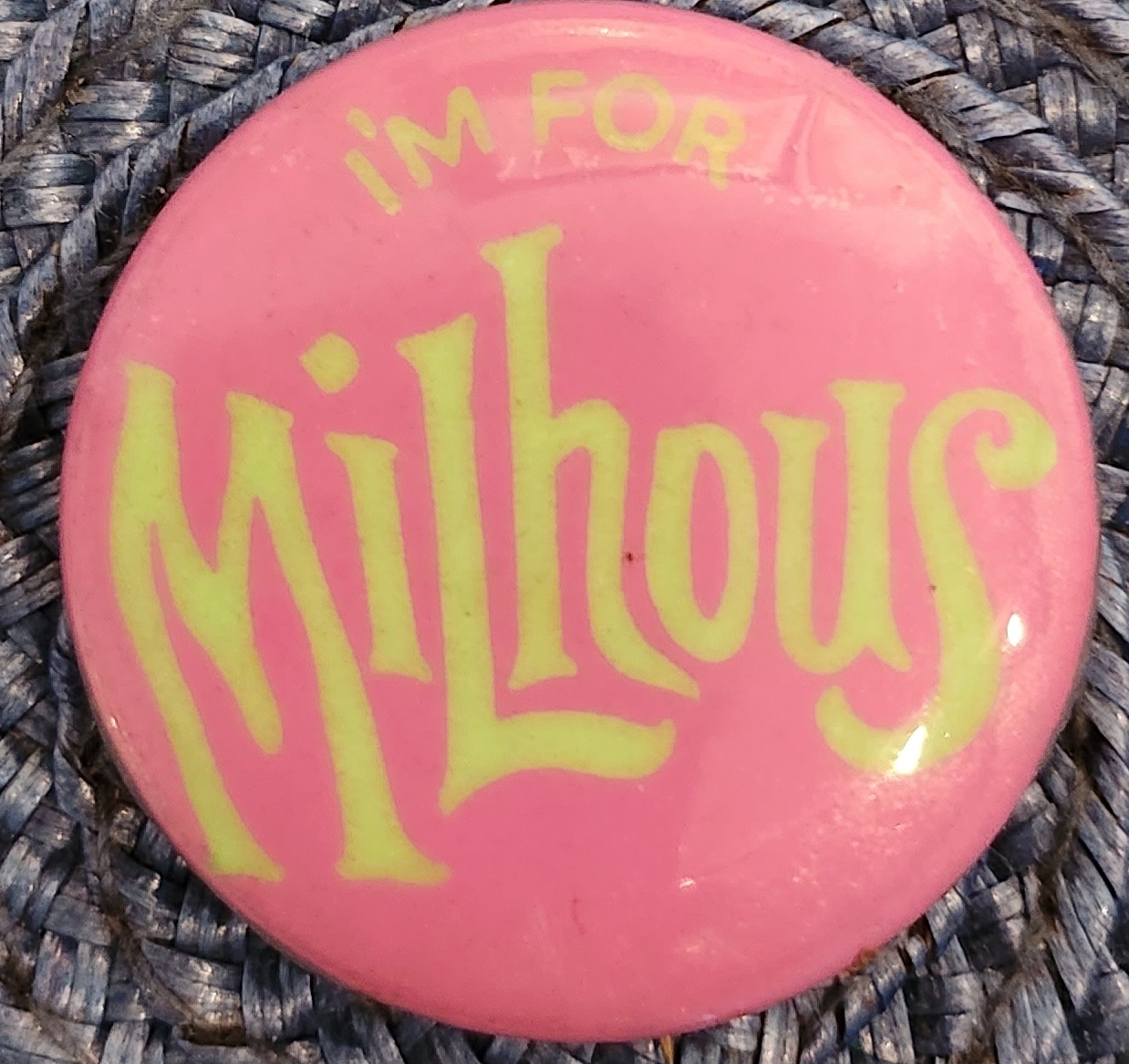

During the 1968 presidential campaign, the group Young Voters for Nixon commissioned Jim Michaelson, a designer of psychedelic rock posters for the band Jefferson Airplane and an imagineer for Disney, to produce the psychedelic poster titled “Nixon’s the One” (fig. 5).50 Michaelson employed the examples of graphic designers Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse, who used stock images and Art Nouveau elements in incongruous ways in their posters to separate images from their established meanings. Michaelson reimagined the traditional campaign poster, employing bunting and patriotic symbols to frame a composite image of Nixon, his supporters, and former Republican competitors. Nixon appears to emerge from the crowd larger than life, wearing a psychedelic campaign button simply stating “Milhous,” his middle name, which became his psychedelic moniker throughout the election cycle. The advertising firm Feeley and Wheeler produced a campaign button emblazoned “I’m for Milhous” in psychedelic letters (fig. 6), and the young women’s group, the Nixonettes, carried signs in the 1968 Republican Convention proclaiming “Nixon is Groovy.”

A 1969 study of the use of broadcast media in the presidential campaign notes how psychedelic references sought to present a new Nixon that contrasted sharply with his square, suburban image during his failed 1960 contest against the youthful-looking John Kennedy. The study credits Nixon’s appearance on the television program Laugh-In, known for its psychedelic-inspired stage set and antics, with dispelling preconceptions of the candidate as stodgy.51

Peter Max and the Mainstreaming of the Psychedelic Genre

Max had adopted psychedelic elements in his work by 1965 and had driven the popularity of psychedelic art for advertising and political purposes, designing a psychedelic-style poster in 1969 as part of the Nixon White House’s campaign against illicit drug use.52 In the foreword to his 1970 Poster Book, his personal assistant during this formative period, Don Pierce, outlines the influence of the West Coast’s psychedelic posters and even the speech patterns of the U25 (people under twenty-five years of age) on Max. Pierce begins and ends the foreword with exaggerations of the term “zap” and also uses it as punctuation points throughout the text to note a transition in Max’s work. “Zap,” in contemporary or hippie lingo, indicates a sudden epiphany that was celebrated in the influential psychedelic comic book of the same title, and Max often refers to his posters as “zaps.”53

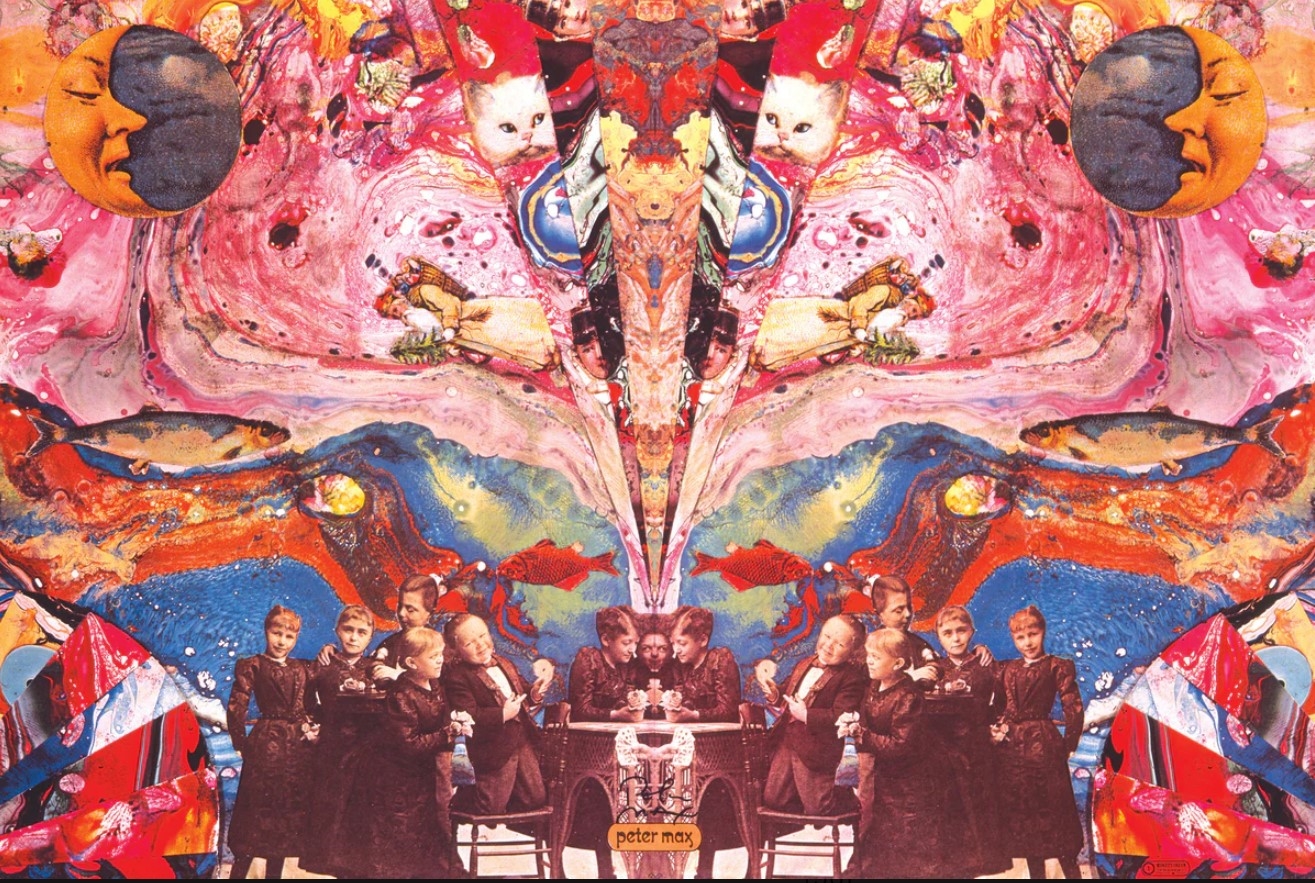

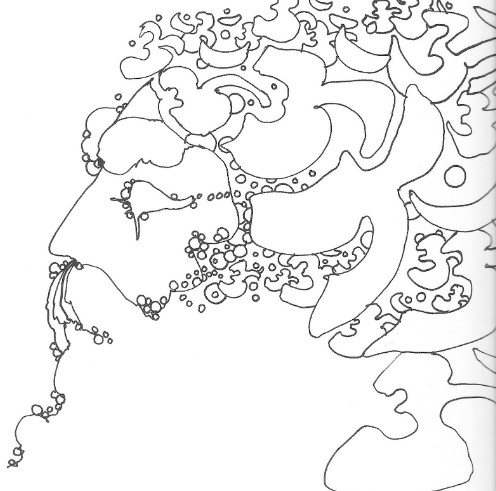

Max characterizes his early poster style as “Cosmic Collage” that reproduced photographs of staid individuals or groups against heavy decorative patterns or amid swirls of colors, as epitomized by Midget’s Dream (fig. 7). He moved away from this style when he adopted the Pentel felt-tip pen for drawing. This marker allowed him to create heavy outlines without lifting the pen from paper. He dubs this technique “flow of the line” and states that it let him transform sumi-e (Japanese black-ink painting) into a distinct style that he called “Cosmic Art.” This claim was an attempt to link his work with Eastern art rather than an actual adaptation of the technique. His pen-and-ink drawing Sat Guru Om (fig. 8) illustrates how he combined the flow-of-the-line technique with poster artist Wilson’s ability to make elements appear to emerge from amorphous shapes. At first viewing, the subject appears to float among a series of squiggles, but with sustained study, the squiggles become recognizable as the yogic om symbol. In his commercial posters, Max added color that enabled the eye to discern elements more quickly within the composition, heightening the emotional response of the viewer.

He developed the elements of his posters into a lexicon that he referred to as the Maxian mind bank. He based this vocabulary on ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock prints), whose figures represent concepts to their viewers. These prints also convey the mise-en-scène or sense of mood and character to works on paper. Most important, their distinctive style makes them easily recognizable and distinguishable from other prints, even by the general public.

Max modeled the figures in his mind bank on the hippies and flower children that he observed in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district and New York’s Greenwich Village.54 The “Cosmic Jumper,” a figure who appears in profile wearing exaggerated bell-bottoms, was internationally known as the embodiment of free and unconventional thought. The brightly colored clothing of the “Flower Flyer” suggests the patched and embroidered clothing worn by the U25s and Max himself. When placed in settings that explode with color, these characters appear to float, untethered by laws of science or convention, and they allow Max to emulate the altered states associated with psychedelic experiences.

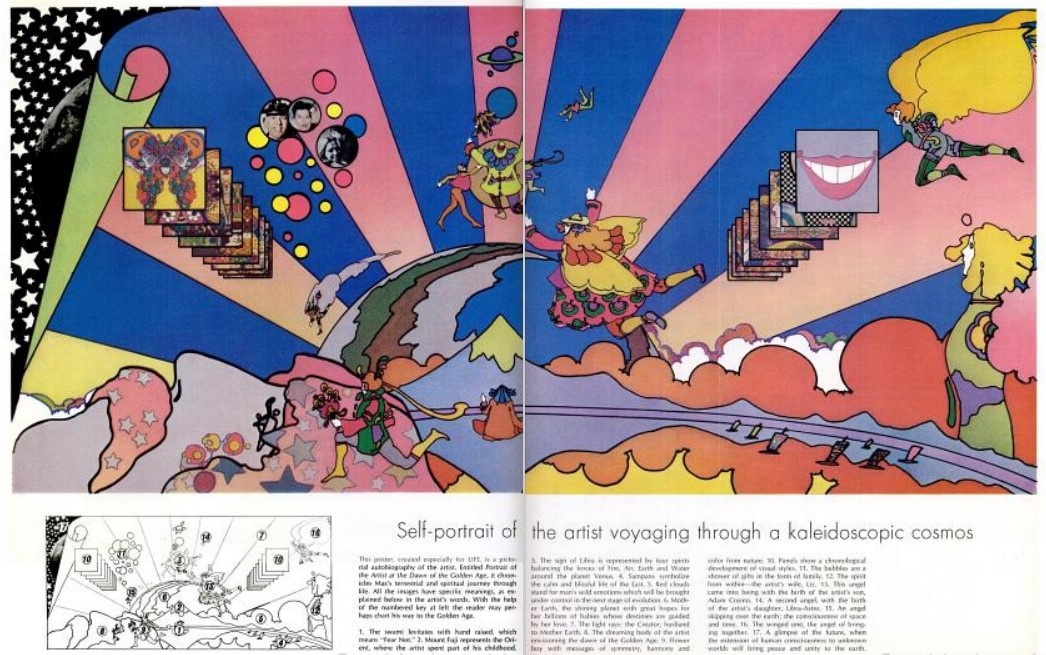

By 1969, Max had codified his mind bank to the extent that Life magazine commissioned and published his design Self Portrait of an Artist Voyaging through a Kaleidoscopic Cosmos (fig. 9).55 This illustration shows a poster—Max’s most popular medium—in the process of being unfurled across the double page of the magazine, its curled-up corner revealing a glimpse of the greater cosmos. The foreground features the face of a reclined Max in profile with a barrage of images emanating from his mind. A mountain transforms into a stream where sampans float bordered by bulbous clouds. Behind this scene, the earth is made radiant by a circus tent–like pattern of sunbeams with floating mind-bank elements representing aspects of Max’s career, detached from time and space. The image was accompanied in the article by a diagram that identified and defined the items from the mind bank. The red sky symbolizes strong emotions. Light rays signify the creator spirit, and the sampans evoke a calm and blissful life.

Standardizing elements in his mind bank allowed Max to conceptualize a range of commercial products that were then developed by his assistants. The Village Voice reported in 1967 that his studio was transforming over four thousand psychedelic concepts into items used by Americans in their daily lives.56 Max described the output as producing three to six products a day that ranged from a line of watches to bed linens and wallpapers.57

In addition, he developed national advertising campaigns that made elements of the mind bank ubiquitous. He designed posters for Metro Transit Advertising in an attempt to convince fifty million people nationwide that bus ridership was hip. His figures appeared in posters on the exteriors of ten thousand buses, coast to coast. As acknowledged by Life, Max dominated the international trend integrating psychedelics into everyday life, and the New York Times exclaimed that Max “was to graphic arts what the Beatles had been to music.”58

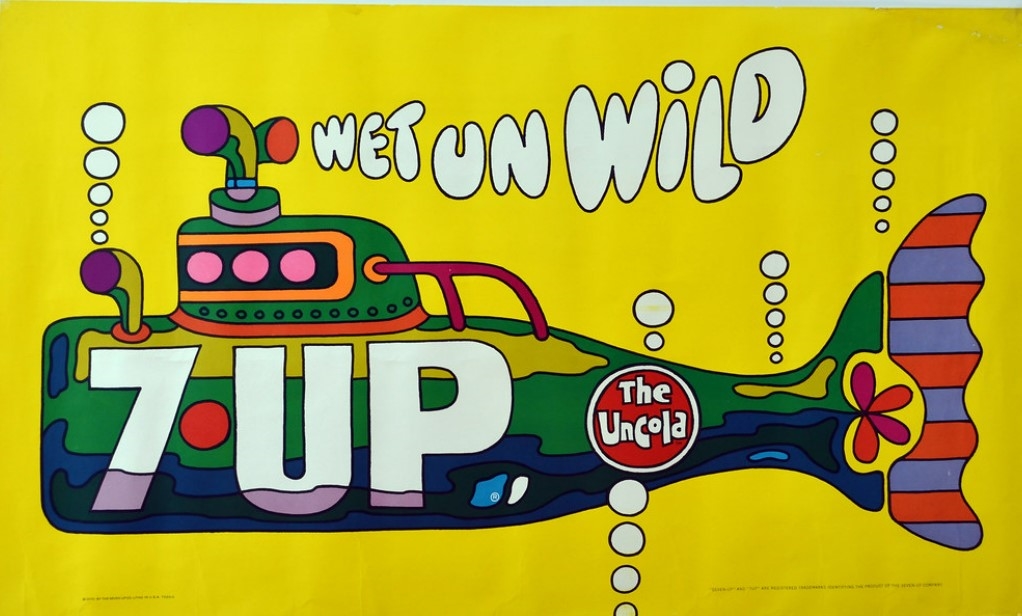

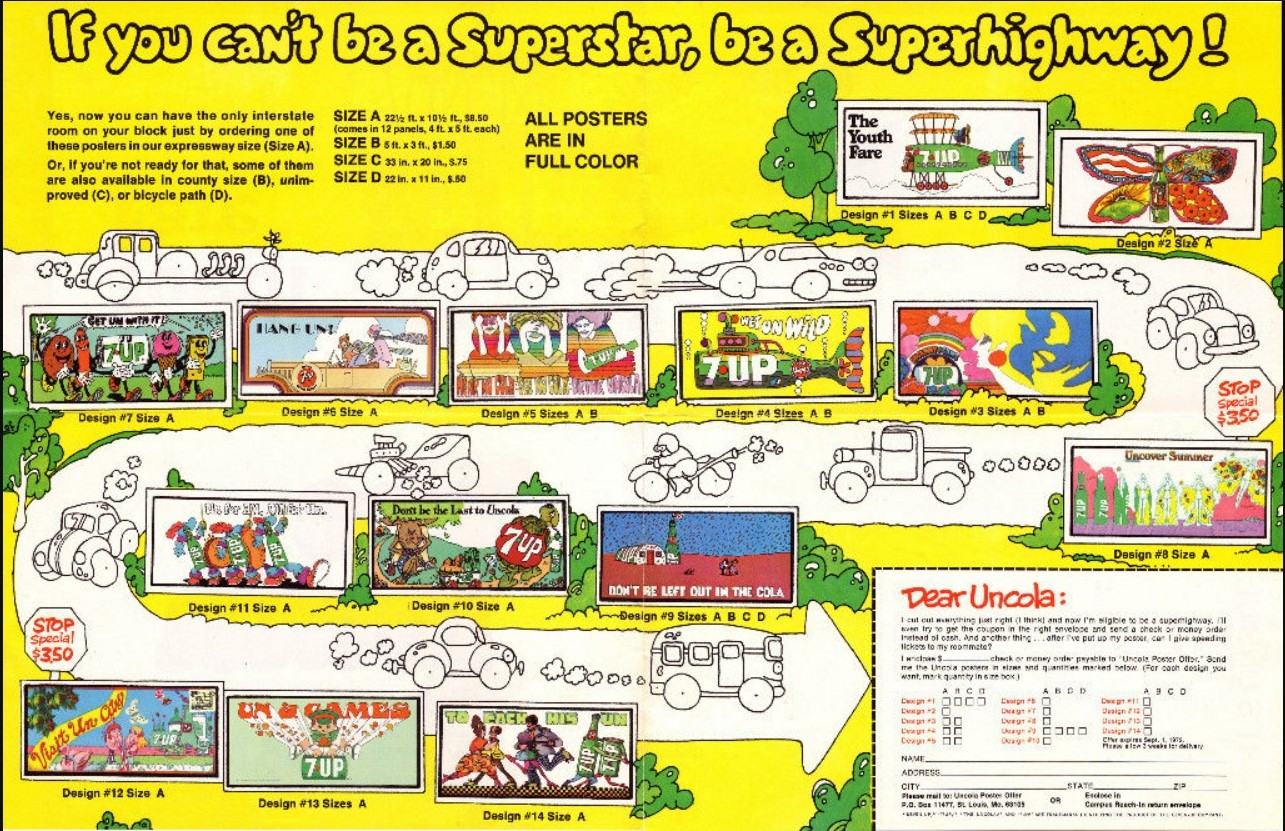

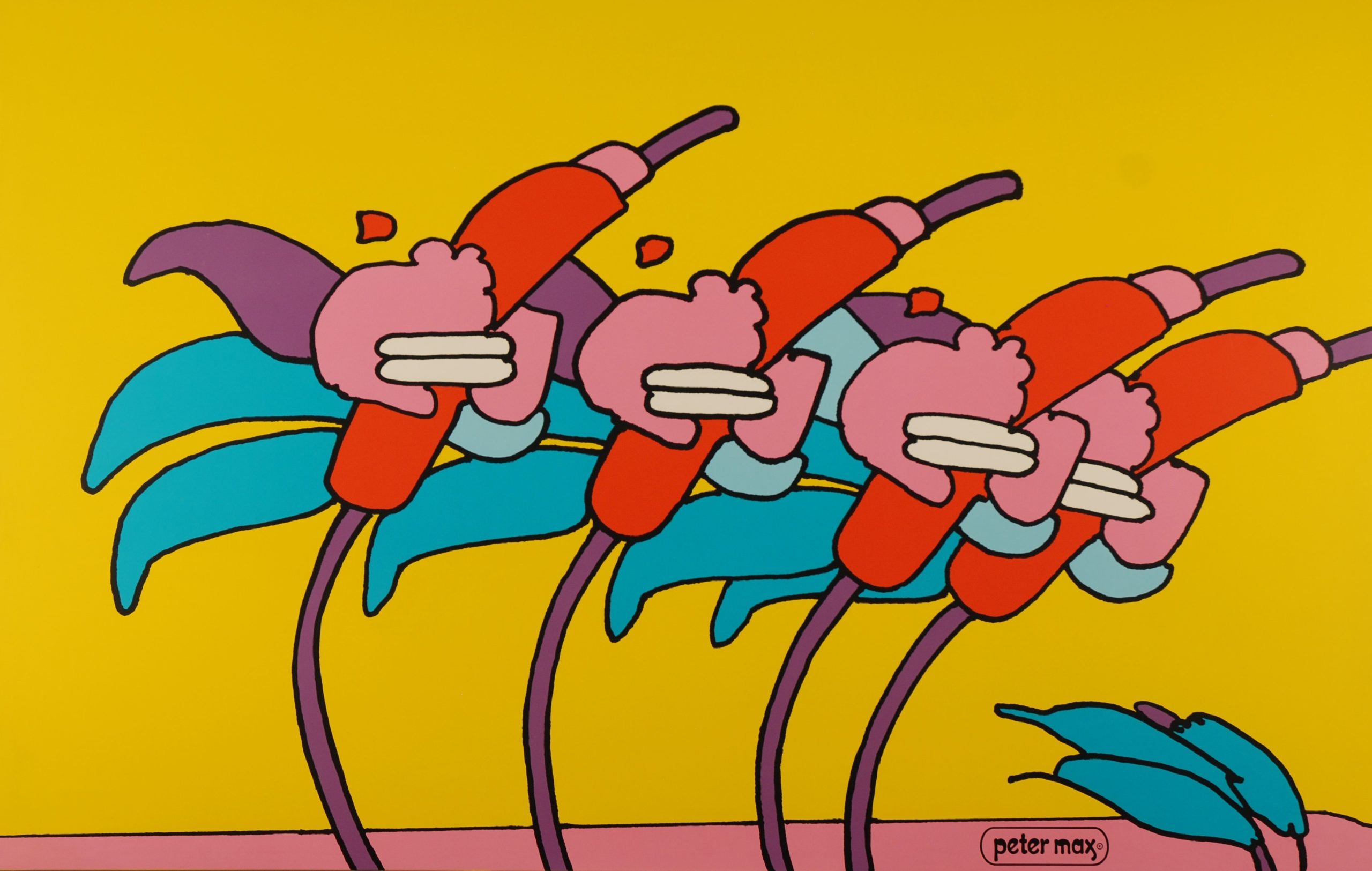

Psychedelic posters—including corporate advertisements—were hailed by Life as the modern art of the masses.59 The best-known advertising series was created for Nixon’s press secretary’s former client 7Up, which changed the soda’s image and increased sales. From 1969 to 1975, JWT mounted a billboard, poster, print, and television campaign that employed psychedelic images to declare 7Up as the preferred alternative to Coke and Pepsi as “the uncola.”60 Ed George, a resident graphic artist at JWT, transformed the 7Up bottle (fig. 10) into a submarine recalling the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine. Images were added yearly, keeping the campaign fresh and building anticipation for the next year’s billboards, which were also marketed as posters through mail-in postcards included as inserts in national magazines (fig. 11). A billboard design by Pat Dypold features the 7Up bottle metamorphosing into a butterfly (fig. 12), which relates to how Sampson wanted the GSA’s art and graphics program to present the transformation of a bloated bureaucracy into a nimble and responsive federalism.

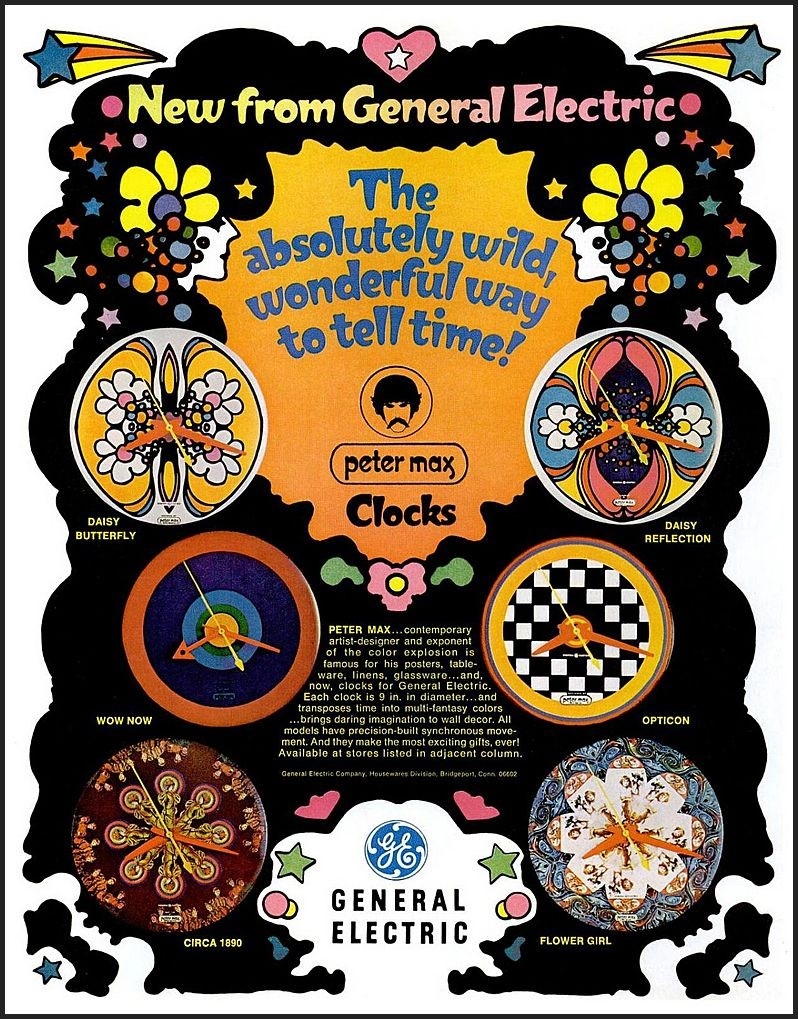

Sampson mistakenly thought that Max had created the 7Up campaign, so he personally awarded Max the welcome sign commission in 1973. Sampson was also familiar with Max’s broader work in transforming corporate reputations, like that of Sampson’s former employer General Electric. Max had created a series of psychedelic clock faces (fig. 13) and was credited by GE for bringing “daring imagination” to a manufacturer known for mundane but reliable products that had been promoted by Reagan in the 1950s.61 In addition, Max’s personal story appealed to Sampson. Max, who was born in Berlin, had fled with his family to China to escape Nazi persecution only to become a refugee following the communist revolution. For Sampson, Max’s success in achieving the American dream made him the ideal choice in creating billboards that would welcome a new generation of immigrants.

Max also shared Nixon’s vision of the bicentennial as the dawn of a new era. As he explains in Peter Max Paints America, a catalogue showcasing a series of works created especially for the bicentennial, “To me this is probably the greatest time in history to be living, especially to be living here in America . . . This is the bicentennial, but it is also the start of the tricentennial. It is my vision that the future will see the United States assuming world leadership.”62 The catalogue’s back cover tied the GSA billboards to Max’s patriotic bicentennial vision.

Psychedelic Greetings at the Nation’s Borders

The selection of Max, known by the moniker of the prince of psychedelic art, was a bold choice to create billboards welcoming international travelers to the United States. Independent from the AIA program, the billboards aligned with the updating of graphics begun under FDIP, as well as Nixon’s bicentennial initiatives that looked to the future and encouraged tourism. The project consisted of a series of seven images, four by six feet, designed to be seen by pedestrians or motor traffic moving fifteen to thirty-five miles per hour. They were to be placed at all border crossings, essentially the entrance lobbies to the nation, with the intent of conveying the new spirit of ’76 as the AiA art installations and the new GSA logo did in government complexes. Below each image was the caption “Welcome to the United States,” with a translation in French or Spanish depending on its placement on the northern or southern border.63

Max reworked his earlier posters for the billboards, where the Cosmic Jumper, the Flower Flyer, and the American Flyer transcend time and float in skies amid stars, rainbows, and planets. In the billboard The American Cosmic Jumper in the Land of Rainbows and Stars, the character appears mid-stride among bubbles that Max employs to convey joy (fig. 14). The Jumper’s energetic pose expresses the exuberance of youth, illustrating Max’s assertion that the United States is the “youth among the nations of the world.”64

A second billboard design, The American Traveler Spreading Good Times (fig. 15), celebrates international tourism and draws from two of Max’s posters, Flyer with Flower (1969) and Flyer with Flower and Two Sages (1971). Here, the Flyer floats among birds, dressed in his familiar colorful and patterned clothing and detached from the background. A third design, Our Flyers in the Stars—America in Space, is more closely aligned with specific themes that Max had developed related to the nation (fig. 16). He replicates his poster American Flyer (1971), with the Flyer reminiscent of Walt Disney’s cartoon pixie, floating against a sky-blue background amid a field of oversized stars. Max had created the American Flyer in homage to the NASA space program, for which he produced posters commemorating the 1960s Apollo missions to the moon. He referred to America’s dominance in space exploration as characteristic of the vitality and creativity of the nation. He also associated milestones in the space program with phases in his career and his own discoveries of new worlds, both “cosmic and artistic.” He notes that he began his partnership with fellow graphic artist Tom Daly in 1962, the same year that John Glenn orbited the earth and that the Apollo flights coincided with the development of his Cosmic Art period.65

Max celebrated the nation’s religious traditions in two billboards. In The Color Spectrum of America—Many Faiths (fig. 17), he uses symmetry to denote balance among the elements that are given a luminescence or aura through harmonizing colors. The four central faces appear in the same plane and are drawn in scale with each other. The rainbow in the middle repeats the colors of the figures in the foreground, implying harmony between them. While the four faces dominate, blotches of color frame them and seem to emerge as faces themselves. The design One Nation under God—This Is a Blessed Country (fig. 18) ties religious tradition with veneration of the country through its title, which is derived in part from the Pledge of Allegiance. It depicts a smiling creator spirit and a city whose skyline is reminiscent of New York. The superimposition of the creator spirit indicates the protective divine force, and its smile reveals the favor it bestows on the nation.

As Max was developing the program for the welcome signs, his association with the environmental movement established him as an unofficial celebrity spokesman. He created the postage stamp for the environment-focused Expo ’74, which shared his optimism in its motto: “Celebrating tomorrow’s fresh new environment.” Max depicts the new environment as a magic land or utopian state, safeguarded by Nixon’s creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.66 Two of the billboards reflect both Max’s and the administration’s advocacy for the environment.

Easy Sailing in the Magical Land (fig. 19) presents conservation as a matter of cosmic balance. Elements of the composition appear to be in conflict with their definition in the mind bank, since the sampan floats effortlessly without creating a wake but is set against a red sky, an element that usually signifies strong emotions. This seeming contradiction expresses Max’s call for the restoration of balance. His writing collaborator and commercial art director, Victor Zurbel, notes that Max originally aligned this imagery with the Chinese Taoist philosophy of Wu Wei (effortless action).67 When he designed posters in the 1970s, Max used elements from the mind bank to reflect the competing interests of modern society and nature while offering a cautionary tale outlining the need to protect the environment. This theme is also present in his Flowers in the Wind—American Breeze (fig. 20). The blossoms represent happiness or euphoria, and their survival is dependent on the quality of the American breeze. Wind both propagates the flowers and threatens them by its force; the ability to nurture relies on balance.

In creating these vignettes, Max expresses what he considered the essential qualities that define America. He purposely did not use traditional icons of national pride, like the flag or the eagle, but rather employed his mind-bank characters to associate the nation’s values with larger cosmic truths that were being revealed to him through his embrace of Eastern mysticism. When the GSA embarked on the billboard project in 1973, Sampson believed the public’s familiarity with Max’s work would lead them to, at least, appreciate the spirit if not full import of the welcome signs. However, by 1976, changes in the presidential administration and public perception made the billboards controversial.

Political Upheaval and a Change in Rhetoric

The years between 1973 and 1976 marked a reversal in Sampson’s political fortune and witnessed the beginning of a controversy over the billboards that lasted a decade. In 1973, he received the President’s Management Award personally from Nixon, but Sampson fell from favor under the new Ford administration because of the release of the White House records to the disgraced former president and the GSA’s expenditures on Nixon’s private property.68 Ford’s deputy chief of staff and the future vice president, Richard Cheney, sought Sampson’s dismissal and enlisted the support of other advisers who agreed that Sampson’s resignation would help distance Ford from Nixon.69 Sampson resisted, hoping to lead the GSA through the bicentennial, but he ultimately resigned on July 28, 1975, and left the GSA on October 15. He spent his final months unveiling AiA commissions, establishing the reputation of his revitalized GSA as the greatest patron of public art of the 1970s.70

Throughout the spring of 1975, the Ford administration was in full retreat at home and abroad. On April 19, 1975, young protestors known as the People’s Bicentennial Committee heckled Ford at the anniversary commemoration of the Battle of Concord, forcing him to leave the event early.71 Four days later, Ford announced the US withdrawal from South Vietnam without an end to hostilities. He intended his remarks to be reassuring, but they only underscored that the nation had lost its way when he said that “Americans can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam.”72 The conservative insurgency within the Republican party did not think that Ford could restore honor and pride to the nation. Their calls for change were emboldened by news coverage that portrayed Ford as hapless and the young protestors at Concord not as idealists, but as drunken revelers.73 The insurgency wanted another candidate for president in 1976 and found him in Ronald Reagan.

The publicity surrounding Ford’s Concord debacle reinforced Reagan’s campaign rhetoric. As governor of California, he had attacked protestors as self-indulgent and went further to blame universities for corrupting the nation’s youth. Coupled with this rhetoric was an accusation that the federal government could no longer be trusted because it was controlled by liberals who coddled the counterculture and favored special-interest groups over the average citizen. When Leary, the liberal activist and celebrated psychedelic guru, entered Reagan’s race for re-election for governor, his candidacy had unintended consequences brought on by his conviction on illicit drug charges, which served to validate Reagan’s rhetoric among voters and solidify his political base. Reagan also contrasted the selfishness of the Me generation personified by Leary with the sacrifices that previous generations had made to build the nation.

Reagan employed this same rhetoric when he entered the presidential race against Ford. As noted by historian Philip Jenkins, Reagan convinced Americans that current conditions were dire “because sixties values had let them get so bad.”74 His point of view was reinforced by the “new journalism” that, as the professor of rhetorical studies Richard Kallan notes, “emphasized opinion over fact.”75 Its premier practitioner, Tom Wolfe, playing on a riff based on Pepsi Cola advertisements, had named the activists from the sixties “not the Lost Generation or the Beat Generation or the Silent Generation or even the Flower Generation, but the Probation Generation.”76 Wolfe traced how psychedelic art, with its “quasi art nouveau swirls of lettering, design and vibrating colors, electro-pastels and spectral Day-Glo, came out of the Acid Tests . . . [and became] works of art in the accepted cultural tradition.”77 He lampooned cultural institutions and satirized “limousine liberals” who embraced social causes and activist groups, like the Black Panthers, because they deemed them fashionable or “radical chic.”78 He exposed the “myths and men of modern art” in the April 1975 issue of Harper’s Magazine that named the art establishment as complicit in the moral decay of American sensibilities. This essay mocked MoMA for repeatedly selecting and employing young artists as “guerilla[s] in the vanguard march through the land of the philistines.”79

This rhetoric resonated with voters, especially after Ford’s debacle at Concord. It came amid a barrage of bad press about ongoing “bicentennial disarray” that led Cheney and presidential adviser John Marsh to attempt to bring commemoration planning under White House control.80 They also wanted to develop bicentennial messaging to address what the historian Natasha Zaretsky identifies as the “intertwined anxieties about national and family decline that had come to the forefront by mid-decade.”81

Cheney and Marsh crafted their approach, as historian David Ryan outlines, to employ nostalgia to abrogate the administration’s association with current events.82 Marsh and Cheney formed the White House Bicentennial Task Force, comprised of political operatives, and developed an action plan: beginning with a presidential New Year’s proclamation, the year 1976 was to be filled with events that celebrated the nation’s distant, heroic past and reminded voters of what was good about America. These activities would then establish Ford’s momentum going into the November presidential election. Individuals or groups who did not uphold these themes were labeled the “competition,” and the task force scrutinized their activities, including applications for rallies and use of government facilities.83

Nostalgic themes were developed in consultation with media experts like Frank Capra, whose movies present the everyday lives of white working-class Americans as idyllic, and Billy Zeoli, a producer of Christian films and syndicated television programs.84 Zeoli publicly replaced Graham as the president’s spiritual counselor. He also became a political adviser and joined with another Ford family friend, Francis Schaeffer, to produce and publicize the multipart television series How Should We Then Live? The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture. Written by Schaeffer, the series rebutted the progress of world culture presented in Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation and Jacob Bronowski’s Ascent of Man.85 Schaeffer drew parallels between the promotion of modern art by cultural institutions and the proliferation of social ills like drug use, especially among college students. He cited Aldous Huxley’s 1954 account of experimentation with LSD, in which Huxley compared his psychedelic experience to the animation of Cubist paintings.86 Schaeffer ended the series with an indictment of cultural elitism and a call for the return to a “God-centered” humanism that restored classical and Western traditions.87 Schaeffer, a Presbyterian minister, had founded an international, politically conservative Christian youth movement as an alternative to hippies and flower children that included Ford’s son Michael and his daughter-in-law Gayle.88 He also held studies of the Bible and humanism with Republican legislators in which he blamed universities and cultural institutions for adopting the “New History” that highlighted social causes and minorities, classified by Wolfe as “radical chic.”89

Vice President Rockefeller, who had served as the president of MoMA and had championed abstract art as representative of American democracy, was emblematic of the cultural elite.90 According to William Rusher, the publisher of the conservative National Review, “Every movement needs a villain . . . For the GOP, Nelson Rockefeller was it.”91 He had battled with Cheney over making the bicentennial into a nostalgia-laced commemoration, and his brother, John D. Rockefeller III, had unsuccessfully called on Ford to sign a bicentennial declaration that recognized the plight of marginalized Americans.92 Cheney harnessed the insurgency’s animosity to oust Rockefeller from the 1976 presidential ticket and attempted to entice Reagan to become Ford’s running mate by adopting his rhetoric.93 Rockefeller’s removal from the presidential ticket signaled the ascendency of Reagan’s viewpoint in the Republican party.

The White House Bicentennial Task Force involved the GSA in its action plan for the national commemoration. It directed the GSA to organize a “Bicentennial Toolbox” to help regional, state, or local government and nongovernment organizations create grassroots political activities as part of the commemoration. Ironically, the creation of the toolbox and Cheney’s efforts to oust Sampson temporarily salvaged the welcome sign project, since the toolbox was submitted by James O’Neill, acting archivist of the United States, instead of the GSA administrator, as protocol dictated. Resources from the National Archives were prioritized, and the welcome sign project was briefly listed in an addendum under “Other GSA Bicentennial Activities Nationwide.”94 It went unnoticed by the task force and was sanctioned by ARBA. In April 1976, ARBA announced in its official newsletter that “Peter Max, a modern art innovator,” had been selected to create “permanent ‘Welcome to America’ murals to greet visitors” at all border entry stations.95

The Billboard Controversy

Disregarding ARBA’s official sanction and announcement to the public, Customs Commissioner Vernon Acree blocked the installation of the billboards, despite Max’s earlier participation in Nixon’s antidrug initiatives. Acree had cited drug interdiction as his first priority when appointed commissioner, calling it a moral imperative to protect “unsuspecting” young people from anti-societal forces that wanted to enslave them to a lifetime of drug abuse.96 Indeed, the Customs Service had opposed Nixon’s drug policy created by Sampson’s political ally Shafer and targeted the counterculture in its training and enforcement. A drill required trainees to locate drugs in a bus painted in psychedelic colors, like the one described by Wolfe in his book the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968). The training included a mock rock song called “Busted at the P.O.E. [Port of Entry],” whose lyrics celebrated agents “on the Mexican border [who] outwitted a band of hippies trying to smuggle marijuana.”97

The political clout of Acree and the Customs Service grew under Ford, as Acree became an adviser to the president on interagency illicit drug policy. He met with Ford on April 7, 1976, and on April 27 Ford asked Congress to expand the role of the Customs Service in drug enforcement.98 That same month, Acree halted the installation of the billboards because he believed that they represented the counterculture and glorified illicit drug use.

After Ford lost the 1976 election to Carter, the GSA revisited plans for installing the signs. Joel Solomon, a Democratic operative with ties to the Carter campaign, became the GSA administrator and saw the blocking of the installation as the Customs Service’s encroachment on GSA authority. He asked the new commissioner of Customs, Robert Chasen, to withdraw the objection. Chasen responded that he had reviewed Acree’s action and concurred with it. The Customs Service officially responded that the billboards conveyed an “image contrary to the border officials’ job for stopping drug traffic.”99

Undeterred, Solomon brought the issue before the national press.100 He noted that the billboards represented “the art of our times,” claiming, “We should accept it.” Through its public affairs office, the Customs Service countered that “modern art . . . is not really for the uninformed traveler” and “presented a poor first impression to people coming to the United States.”101 Moreover, Customs asserted that the depictions of the counterculture of the 1960s were not representative of American ideals but were an endorsement of an anti-establishment mindset and illicit drug use.

Solomon appealed directly to the president, citing the administration’s policy of “let’s use what we’ve got.” Carter reviewed the images and deemed them “very appropriate” representations of the nation to welcome international visitors.102 He prevailed on Chasen to drop his objection and to display Max’s originals at Customs headquarters during a press conference. Carter noted that the billboards supported his and First Lady Rosalynn Carter’s desire to bring the “twentieth century into the White House” by promoting contemporary American art, an initiative that began on his first day in office when he invited five artists to produce works capturing their impressions of his inauguration. The First Lady introduced crafts into the White House interior design, installed Max’s painting Peaceful Planet in the private quarters, and placed the originals for the billboards in the White House pressroom.103

The installation and unveiling of the billboards along the borders were prescribed by the GSA. Trial installation at selected sites on the Canadian border began in 1977 and were personally supervised by Masters to encourage public support and build anticipation in the press for their official unveiling. Installation was completed by June 1978, and a month later the federal government executed unveiling ceremonies at more than 150 border entry stations on Independence Day.104

The main ceremony was held at the Ellipse in front of the White House with Carter’s son Jeff and daughter-in-law Annette speaking to the audience and the press in support of the billboards. The satellite ceremonies at the border were implemented by Customs and INS personnel according to the GSA’s detailed plan. A joint Customs-INS memo directed staff to engage the public to pose for pictures in front of the billboards and emphasize to attendees that similar ceremonies were occurring at all border crossings and in the capital cities of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. These photographs of visitors were sent to the GSA headquarters for dissemination to the press and inclusion in GSA publications (fig. 21).105

The GSA reported no negative reactions at the ceremonies, but people crossing both the northern and southern borders began to complain to members of Congress within days of the unveiling. They cited images of flower people and hippies appearing in the billboards and their association with illicit drugs. Congressman Ron Marlenee summarized them in a letter to the GSA:

I am certain that you realize that the type of art is psychedelic in nature. This form of art has been associated with the drug culture and my constituents do not think that the U.S. government should be in any way connected with the promotion of the illegal drug movement.106

These public concerns reflected a failure of the billboards to convey a sense of the nation or its values. A central tenet of the complaints was that the billboards lacked what the cultural historian John Bodnar identifies as the “symbolic language of patriotism” that incorporates “meanings dear to a number of social groups” to communicate what Kammen outlines as the “memories, legends, and traditions that are truly venerable” because they are “time sanctioned myths.”107 A letter to Senator Harrison Williams asked, “What happened to the American flag or the bald eagle?”108 Other complaints questioned why the American flag had been replaced by hippies and flower children.

The delay in the installation also affected the billboards’ reception by the public. Although Max’s work was established in popular culture, by 1978 the images seemed dated and reminiscent of a bygone fad whose origin was now considered suspect. Even Max’s other bicentennial commission of images of the American states had been characterized by a reviewer in the Atlantic “as one of the odder tributes to the Bicentennial.”109 A year after the billboards’ installation, US News and World Report described them as oddities, highlighting the public’s negative comments, ranging from “simplistic” to “comic strip art,” with no quotations praising or supporting the billboards.110 Objections continued into the Reagan administration, with Customs Commissioner William von Raab convincing the GSA to remove the last remaining sign ahead of the 1984 presidential election.

Max’s Response to the Billboard Controversy

Max moved quickly to counter criticism when the billboard project was temporarily halted in April 1976. He announced a drastic change in both his life and work in a September 1976 interview with People magazine that led with the headline: “Once Lost in his Psychedelic World, Peter Max has Subdued his Art and his Life.”111 The change also corresponded to a declining demand for his work, and Max acknowledged the “season is over” for psychedelic-themed art and consumer goods.

He noted that he had banished from his art “starred-covered gurus who leapt from planet to planet in brightly colored robes,” replacing them in the mind bank with a new series of “settled” characters that represent a “highly developed society.” He explained that this marked the next chapter of his artistic journey, which he called the “New Expressionism.” Stylistically, he separated these periods by abandoning his heavily outlined flow-of-the-line figurations characteristic of his psychedelic Cosmic Art for swaths of color created by quick and broad brushstrokes that he believed infused his new compositions with vitality.

He also announced a project to inaugurate his New Expressionism. He told the magazine that he had spent July 4, 1976, painting an image of the Statue of Liberty in his new style and that he intended to devote future Independence Days to creating a new rendition of the statue (fig. 22). When the billboard project was resurrected by the Carter administration, he worked with the GSA to combine their unveiling with the official debut of his Statue of Liberty project. The date of the unveiling, July 4, 1978, was associated with the two hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Monmouth, which convinced the French to enter the Revolutionary War on the American side, a moment highlighted in the ceremonies as the beginning of the friendship between the two countries that led to the gift of the Statue of Liberty. This association broadened the focus of the billboard unveiling ceremony in Washington, DC, to feature Max’s gift of his painting of the Statue of Liberty and its acceptance on behalf of President Carter by his son and daughter-in-law, as noted on the front of the ceremony’s program (fig. 23).

Following the change in presidential administrations in 1980, Max used his Statue of Liberty project to ingratiate himself with the Reagans. He painted six versions of the Statue of Liberty before guests assembled by the First Lady at a White House celebration on July 4, 1981, which were then circulated abroad by the federal government. Max also joined the effort to restore the Statue of Liberty led by businessperson Lee Iacocca, and Reagan praised his series at a White House event for heightening awareness of the restoration campaign.112

While Max successfully reinvented his art and public persona, he failed to establish himself or his New Expressionism’s place in the canon of American painting. He told the New York Times that he had developed New Expressionism for museum collections and the public art of the federal government, signaling that he would concentrate on the creation of original works instead of mass-produced designs.113 But by 1986, he acknowledged that he had not attracted these commissions and had created a “raft of work” for consumers.114 He claimed that his popularity and personal notoriety had prevented him from being accepted by the American art establishment but countered that history would compare him favorably to Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who had not accomplished as much as he had when they were his age.115

His long-term relationship with the commercial Park West Gallery, dating from the 1970s, aided Max in maintaining his popularity. Created in 1969 by Albert Scaglione, Park West marketed Max as America’s “painter laureate.”116 In addition to its showrooms and online presence, the gallery began hosting live auctions on ships across Norwegian, Carnival, and Royal Caribbean cruise lines in 1995 with Max frequently in attendance. The resulting demand for work led Max to again rely on assistants to increase output, raising questions about authenticity. By 2019, the New York Times questioned if dementia had stopped Max from painting.117

The Backlash against Public Art Commissions

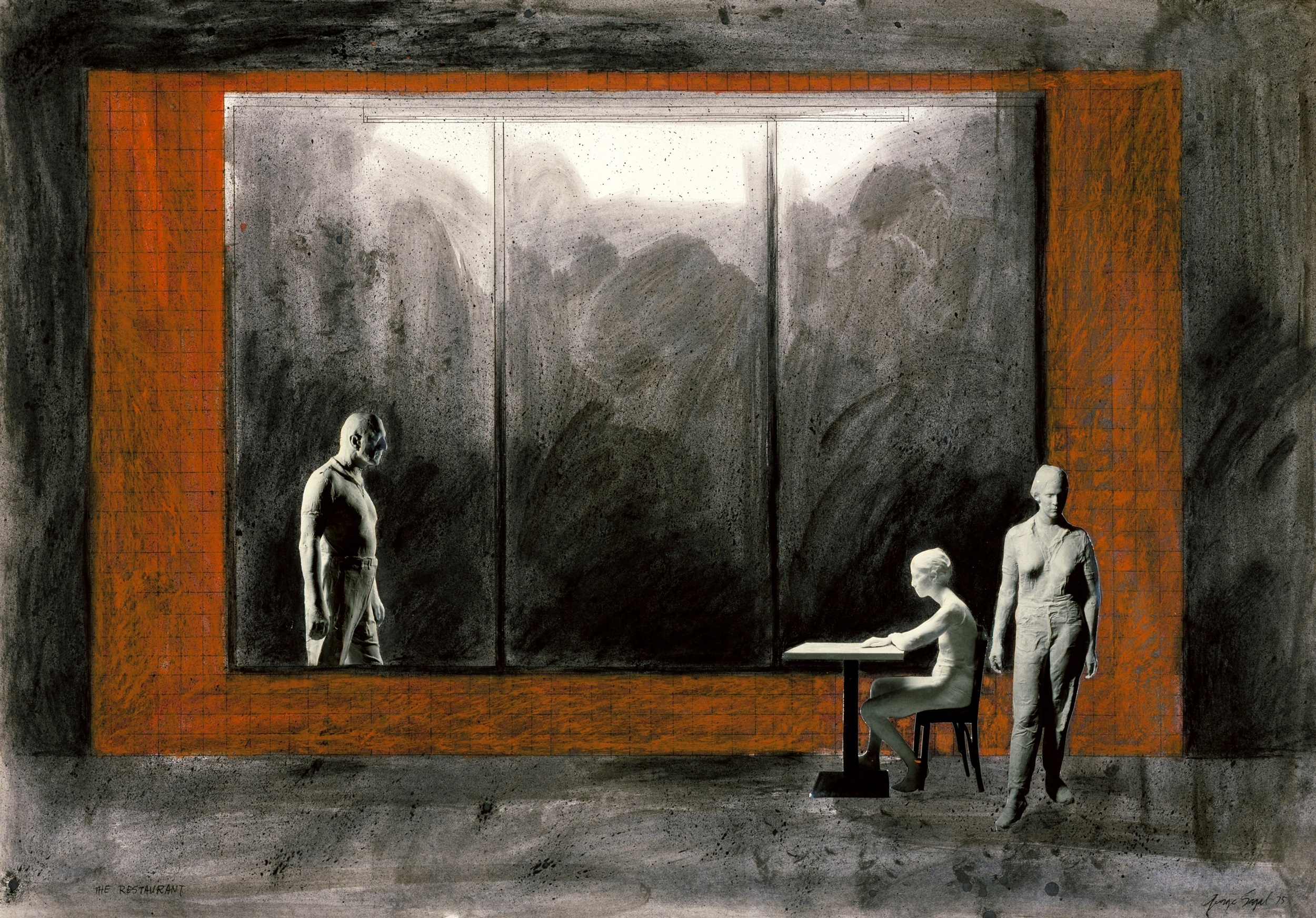

The billboard debate proved a bellwether for ongoing art controversies within the federal government. It occurred amid a broader backlash against the AiA program, with complaints about designs and the meaning of commissions receiving a sympathetic hearing from Sampson’s successor, Jack Eckerd. Eckerd withdrew the GSA from the 1976 unveiling of George Segal’s sculpture Restaurant (fig. 24), which depicted a chance encounter among a man and two women, because detractors claimed it was sexually suggestive.118 He also halted new commissions for the duration of the Ford administration.

Despite Hanks and Sampson’s attempt to portray AiA as a means to provide art for everyone, critics of the program during the Carter administration depicted it as an example of federal government overreach and crystallized their argument in what the Washington Post dubbed the “Showdown on Hoe Down.”119 The sculptor Guy Dill designed the forty-five-foot-long steel-and-wood Hoe Down (fig. 25) installed at Huron, South Dakota, as a tribute to the state’s agricultural traditions, but he incurred the ire of residents who resented that a California-based sculptor, selected by a panel of outside experts, had reduced their contribution to the nation to “four large plates propped up by telephone poles.” The Huron Daily Plainsman reported that the public rejected the sculpture because “they had no say in what went up here.”120

Huron’s Republican Congressman James Abdnor elevated the controversy to a national debate through congressional hearings and by trumpeting the Washington Post’s account of the AiA program titled “Don’t Laugh, It’s Your Money.”121 Abdnor incorporated the controversy into his 1980 Senate campaign against incumbent George McGovern. Evoking themes from the Capra movie Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Abdnor depicted himself as restoring the common-sense voice to Washington, and his defeat of the liberal icon was viewed as a repudiation of the state’s progressive traditions.122

The backlash against federal art commissions was further magnified in the controversy over Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam Memorial. Bolstered by a Wolfe essay, the opposition rhetoric distilled its argument that modern art and architecture were antithetical to Americans’ sensibilities into emotional speaking points.123 Tom Carhart, a Vietnam veteran, described the sleek modernist design as an insult to those who served in Vietnam by intellectuals and cultural elitists and called it a tribute to antiwar activists.124 Even the selection of materials and siting for the monument were considered an affront that equated the Vietnam War to a “black gash of shame.”125

When controversies over AiA commissions erupted in Baltimore and New York City, the New York Times dubbed abstract works as privileged and questioned if they should be imposed on the public:

The case bears on the very nature of public sculpture itself, and its ‘’responsibility’’ to a broad general public. Once sculpture steps out from the privileged context of a museum or gallery—where it is viewed voluntarily—and onto a public site, it is imposed on the tastes of a mass of people many of whom have no esthetic understanding of, and may even actively resent, its presence. Should such sculpture be of a different order—i.e., non-abstract, relating to community themes—than that made for the audience that frequents museums? Or should esthetic integrity not be compromised, thus educating a larger public to the standards of serious art?126

The Reagan administration advocated for nonabstract works and voiced its argument not by the NEA but by National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) chair William Bennett, who declared art as a discipline within the humanities and advocated its study for “humanity’s sake.”127 He acknowledged modern art’s role as iconoclastic, pronounced it as an attack on American values, and called for a return to classical and Western traditions. An NEH-funded seminar cited the Hoe Down commission as an example and examined why the sculpture was antithetical to Midwestern values and why Americans considered it an insult and a boondoggle.128

Bennett enlisted the art critic John Canaday, who had advocated for a return to representational art, which he dubbed an Americanization of modern art, during the bicentennial. Canaday claimed that a retrospective embrace of Western and classical traditions in art could advance the progress of civilization by creating the myth of an idyllic past that was necessary to sustain a great society.129 This rhetoric and Bennett’s call for education reform, titled To Reclaim a Legacy, became the basis for Richard Cheney’s wife Lynne and a subsequent NEH chair to advocate for heritage over history. She criticized schools for not embracing nationalist myths, calling them a “threat to American memory.”130 Folded into this discussion was a rejection of the New History that questioned the traditional narrative and advocated for examining the past from competing points of view, inclusive of those individuals and groups that had been minimized or excluded from American history.131 Support and reaction to Bennett’s and Cheney’s rhetoric became aligned with party politics. Their position was rejected by progressive groups and educators who accused them of “wistful nostalgia” and “knee-jerk formalism.”132 It was also rejected by the Democratic chairs of NEA and NEH, and Daniel Geary has outlined how both Democratic and Republican presidents appointed NEA and NEH chairs who have increasingly employed their positions as bully pulpits to “push the substance of grant making in progressive and traditional directions, respectively, despite continuity of formal rules, procedures and staff.”133

The GSA remains a pawn in this debate, with criticism directed at both its architecture and art programs by conservatives who claim that expert advisory panels isolate its commissions from the will of the public. To counter what was depicted as a slight toward average taxpayers, former President Donald Trump issued an executive order that censured modern architecture and directed that traditional and classical styles should be the “preferred and default” style for government buildings. He required statuary to be “lifelike or realistic representations of the persons they depict.”134 He linked these requirements to his 1776 Commission, meant to counter the New History and the 1619 Project in order to restore the mythic view of American history. Democrat Joseph Biden promptly rescinded Trump’s executive orders when he entered office in 2021, citing their exclusivity and the need for the government’s art, architecture, and rhetoric to reflect the experience of all Americans.

Conclusion

Despite the GSA and the Customs Service’s attempt to frame the debate about the acceptance or rejection of modern art, the billboard controversy did not concern Max’s images as works of art. Instead, the controversy was driven by the perception among a segment of the population who considered themselves quintessential Americans that a point of view was being imposed on the public that was antithetical to their values by a burgeoning bureaucracy that favored special interests to the detriment of mainstream society. As the debate over public art broadened in the 1970s and ’80s, the portrayal of modern art as representing ideological and political factions, not its intrinsic aesthetic value, influenced public opinion. For many Americans, it is what Kramer identified as extra artistic standards which affirm their ideological, social, and ethnic identity that determine the ability of art to represent the nation.

Cite this article: David McKinney, “Psychedelic Patriotism: Peter Max Sparks a Debate on Modern Representations of America,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18740.

Notes

A portion of this article was presented at the University of Virginia on November 16, 2019, at the symposium “Richard Guy Wilson and Our Community of Scholars.” Thanks to Marilyn Farley for discussing Arthur Sampson and the GSA under his administration with the author, to Professor Wilson and Sandra Rusak Cage for their review of the initial draft, and to the editors of Panorama for their guidance.

- “GSA Bilingual Signs to be Dedicated at Border,” June 8, 1978, GSA press release #6915, Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request GSA-2019-00170. The press release explains that the signage was part of the updating of graphics by the federal government. A memorandum from Donald W. Thalacker to William F. Sullivan of May 8, 1984, outlines Sampson’s role in the welcome sign project. This memo is accompanied by a summary of the project prepared by Marilyn Farley, who had served as Sampson’s assistant (FOIA request GSA-2019-00170). The references to “fresh and modern” were used by the Nixon administration to separate FDIP from the Kennedy standards and attempt to portray them as outdated. See Rita Reif, “Fresh Look Is Due in Federal Design,” New York Times, February 12, 1973. ↵

- Cynthia B. Meyers, “Psychedelic and the Advertising Man: The 1960s Counter Cultural Creative on Madison Avenue,” Columbia Journal of American Studies 4, no. 1 (2000): 114. A counterculture newspaper in San Francisco identified those who “sell counter-cultural wares because of their market value” and lamented that “New Age is beginning to look like any big establishment business”; “The Age of Acquireous,” Good Times 3, no. 49 (December 11, 1970): 10–11. See also Joshua Clark Davis, “The Business of Getting High: Head Shops, Countercultural Capitalism, and the Marijuana Legalization Moment,” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics and Culture 8, no. 1 (2015): 8; and Scott B. Montgomery, “Radical Trips: Exploring the Political Dimension and Context of the 1960s Psychedelic Poster,” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 13, no. 1 (2019): 121–54. ↵

- Judith Martin and Amy Nathan, “Turning Around GSA’s Max Nix,” Washington Post, August 11, 1977. Martin and Nathan note that both the Customs Service and the GSA depict the “controversy in terms of acceptance or rejection of modern art.” ↵

- James T. Wooten, “Bicentennial: Patriotic and Commercial,” special, New York Times, July 4, 1974. ↵

- Thomas A Johnson, “Few Blacks Inspired by Bicentennial,” New York Times, July 8, 1976. ↵

- Matthew Frye Jacobson notes that these efforts blended “the mutual engagement of grass roots ethnic activity and state-sponsored heritage,” in Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post Civil Rights America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 54. John Bodnar outlines how ethnic groups “paid homage to the American nation-state and presented their members as legitimate American patriots,” in Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 75. They also shaped how the past was perceived and presented. Richard Sommer and Glenn Forley note that while history subjects “the past to scrutiny,” heritage is an “effort to form an ostensibly more durable set of social codes, behaviors, and political beliefs,” in “The Retraining of History as Heritage,” in Commemoration in America, ed. David Gobel and Daves Rossell (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 130. ↵

- Program for the Minnesota American Swedish Bicentennial Festival, April 10, 1976, Digital Resource Commons Library, University of Cincinnati. Other white ethnic organizations, like those associated with Italian-Americans, sought the president’s endorsement of their activities. See box 72, folder “White House Bicentennial Task Force—Meetings (1),” John Marsh Files, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. ↵

- M. Todd Bennett, “Time to Heal the Wounds: America’s Bicentennial and U.S.-Sweden Normalization in 1976,” in Reasserting America in the 1970s: U.S. Public Diplomacy and the Rebuilding of America’s Image Abroad, ed. Hallvard Notaker, Giles Scott-Smith, and David J. Snyder (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 223. ↵

- Barbara S. Groseclose, “Washington Crossing the Delaware: The Political Context,” American Art Journal 7, no. 2 (November 1975): 78. The National Collection is now the Smithsonian American Art Museum. ↵

- Hilton Kramer, “A Franklin and Jefferson Package at Met,” New York Times, March 5, 1976. ↵

- Hilton Kramer, “Black Art or Merely Social History?” New York Times, June 26, 1977; Grace Glueck, “2 Centuries of Black Art at Brooklyn,” New York Times, June 24, 1977. ↵

- Christin J. Mamiya, “We the People: The Art of Robert Rauschenberg and the Construction of American Identity,” American Art 7, no. 3 (Summer 1993): 45. ↵

- John Canaday, “A Critic’s Valedictory: The Americanization of Modern Art and Other Upheavals,” New York Times, August 8, 1976. ↵

- John Russell, “Jefferson a Winner at the National Gallery,” special, New York Times, June 5, 1976. ↵

- Kramer, “Black Art or Merely Social History?” ↵

- Grace Glueck, “Art in Public Places Stirs Widening Debate,” New York Times, May 23, 1982; Michael Kammen, Visual Shock: A History of Art Controversies in American Culture (New York: Vintage, 2007; Kindle ed.), 278. ↵

- Steven C. Dubin, Arresting Images: Impolitic Art and Uncivil Actions (New York: Routledge, 1992), 37. ↵

- Wooten, “Bicentennial.” See also Richard Nixon, “Remarks to Members of the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission,” October 8, 1969, American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu (hereafter APP). ↵

- The 1968 campaign opened a fissure within the Democrats’ traditional coalition that spurred a third-party candidate, breaking their hold on the “solid South.” Nixon’s political adviser Kevin Phillips outlined the strategy for winning over disaffected white ethnic groups in the book The New Republican Majority (1969). See James Boyd, “Nixon’s Southern Strategy,” New York Times, May 17, 1970. Historian Bruce Schulman notes that the Nixon administration put the Phillips doctrine in practice by uniting the hard hats, the forgotten Americans, and Middle Americans against “bureaucrats and pointed headed intellectuals,” in The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture (New York: Free Press, 2001), 200. Patrick Buchanan identifies the constituencies of the Nixon coalition as “the solid centrist GOP base that had stood by {Nixon} in 1960, the rising conservative movement . . . , the northern Catholic ethnics of German, Irish, Polish, and other descent, and the Southern Protestants, who saw themselves as abandoned by a Democratic Party,” in The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose from Defeat to Create a New Majority (New York: Random House, 2014), 293. ↵

- Leonard Robins, “The Plot That Succeeded: The New Federalism as Policy Realignment,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 10, no. 1 (Winter 1980): 104. ↵

- Ted Koppell, quoted in David Greenberg, “The Selling of Joe McGinniss {sic},” Politico, March 12, 2014. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/03/joe-mcginniss-the-man-who-pulled-back-the-curtain-104610. Greenberg discusses the work of McGinnis, who outlined the use of advertising by Nixon’s campaign and administration, in Selling of the President 1968 (New York: Trident, 1969). ↵

- Reif, “Fresh Look Is Due in Federal Design.” ↵

- Richard Nixon, “Statement on Appointing Nancy Hanks as Chairman, National Endowment for the Arts,” September 3, 1969, APP. ↵

- Howard Taubman, “Nixon Urges Wider Support for the Arts,” New York Times, May 27, 1971. ↵

- Frank Getlein, “The Man Who’s Made ‘the Most Solid Contribution to the Arts of any President Since FDR,”’ New York Times Magazine, February 14, 1971, 14–26. ↵

- Richard Nixon, “Memorandum About the Federal Government and the Arts,” May 26, 1971, APP. ↵

- Ivan Chermayeff et al., The Design Necessity: A Casebook of Federally Initiated Projects in Visual Communications, Interiors and Industrial Design, Architecture, Landscaped Environment (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1973), 5. ↵

- On Sampson’s relationship with Nixon, see Matthew G. Brown, “The First Nixon Controversy: Richard Nixon’s 1969 Presidential Papers Tax Deduction,” Archival Issues 26, no. 3 (Summer 1993): 45. ↵

- See the profile of Sampson in Douglas Watson, “GSA’s Blunt Chief” and “GSA Chief: Tireless and Controversial,” Washington Post, April 6 and 7, 1975. These articles, along with extensive background on Sampson, are found in box 18, Philip Buchen Files, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. ↵

- “Arthur Sampson Breaks Trails for Federal Building” read into the proceedings record. Government Printing Office, Nomination of Arthur F. Sampson, Hearing before Committee on Governmental Operation . . . 93rd Congress, first session, June 18, 1973, 3. ↵

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Must Bad Buildings Be the Norm?” New York Times, March 11, 1973. ↵

- Kammen, Visual Shock, 209. See also Saul K. Gandhi, “The Pendulum of Art Procurement Policy: The Art-in-Architecture Program’s Struggle to Balance Artistic Freedom and Public Acceptance,” Public Contract Law 31, no. 3 (2002): 545. ↵

- Hanks was well versed on the issues related to modern art and how to counter opposing arguments. As executive secretary for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, she directed a study on the economic and social problems of the arts in the United States that also advocated for a federal model for funding arts programs for every American regardless of geographic location as a means to protect freedom of expression: Rockefeller Panel Report on the Future of Theater, Dance, and Music in America: The Performing Arts (New York: McGraw Hill, 1965). Her work dovetailed with the research of Jane DeHart Mathews. The Rockefeller Report anticipated Mathews’s study of the federal theater project during the New Deal, published in 1967. In 1968, Mathews produced the study Government Support of the Arts, which refuted the “time-worn argument that government support inevitably means control” and argued that “such support has enhanced immeasurably the opportunities for freedom of expression by encouraging expansion of the arts and by making arts institutions sites for the kind of exploration and experimentation that would otherwise have been impossible” (American for the Arts: National Arts Administration and Policy Publications Database, https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/government-support-of-the-arts-a-preliminary-inquiry-into-the-problem-of-artistic-freedom-and-public). In a paper before the American Historical Association in 1974, Mathews described the attacks on modern art by anticommunists as blending “fact with fantasy” and identified Hanks’s mentor, Nelson Rockefeller, as an “enlightened anti-communist” who employed modern art to promote American ideals. She published an expanded version of her paper in 1976: “Art and Politics in Cold War America,” American Historical Review 81, no. 4 (October 1976): 762–87. Eva Cockcroft outlined how the Rockefeller family exploited Abstract Expressionism for their own political ends, in “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” Artforum 12, no. 10 (June 1974), reprinted in Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, ed. Francis Frascina (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 133. ↵

- Sean Wolfgang, “Nancy Hanks Is Dead at 55,” New York Times, January 8, 1983; Carl Hill, “Nancy Hanks’ Gentle Persuasion,” Washington Post, January 10, 1983. See also Lawrence D. Mankin, “Public Policymaking and the Arts,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 12, no. 1. (June 1978): 41–42. ↵

- On the popularity of Calder’s works across corporate, art, and architecture communities, see Joan Marter, “Alexander Calder’s Stabiles: Monumental Public Sculpture in America,” American Art Journal 11, no. 3 (July 1979): 79. For Calder’s relationship with Kendall, see 79–80. ↵

- Mel Gussow, “Thanks to Calder Ford Changed Endowment Tune,” New York Times, August 19, 1973; in box 46, folder “President—Medals, Medal of Freedom—Calder, Alexander,” Philip Buchen Files, Gerald R. Ford Library. See also Robert Sherrill, “What Grand Rapids Did for Jerry Ford and Vice Versa,” New York Times, October 20, 1974. ↵

- Carol Oppenheim, “A Whatchama-Calder Conquers the City,” Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1974, reprinted in Chicago Tribune, Public Art in Chicago (Chicago: Agate, 2016). ↵

- Richard Nixon, “Address to the Nation Announcing Plans for America’s Bicentennial Celebration,” July 4, 1972, APP. ↵

- Prepared remarks for Arthur Sampson, box 1, folder “1976/01/13—Louise Nevelson Sculpture Unveiling, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” Frances K. Pullen Papers, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. ↵

- General Services Administration, A New Way: General Services Administration Annual Report, 1972 (Washington, DC: GSA, 1972), 1. Also included in the plan was the creation of internships and programs to attract young people into government who would break the bureaucratic hold of established federal employees, also a component of Nixon’s strategy. ↵

- For a summary of David Rockefeller’s philosophy and practice, see Alex J. Taylor, “Chase Manhattan’s Executive Vision,” Forms of Persuasion: Art and Corporate Image in the 1960s (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022), 95–133. ↵

- Rudolf Arnheim, Visual Thinking (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 145–46. ↵

- Masters’s life and career are described in John Kelly, “Those Brown Signs Outside Federal D.C. Buildings Are Disappearing,” Washington Post, March 15, 2015; and Matt Schudel, “Peter Masters” (obituary), Washington Post, March 23, 2005. ↵

- Timothy Leary, “The Second Fine Art: Neo-Symbolic Communications of Experience,” Psychedelic Review, no. 8 (1966): 9–11. ↵