Library and Gallery Exhibitions as Public Scholarship

Public Engagement with Images of Ethnicity, Gender, Place, Race, and War in Illustrated Sheet Music

In her introduction, Laura Holzman describes a spectrum of public scholarship, from traditional art historical scholarship to democratically engaged practices and products. My work curating exhibitions of illustrated sheet music falls in the middle, serving the public yet not collaborating with it, while transforming lives in activist ways. It is a form of democratic activism that engages people in conversation about the intersections among imagery, music, social and political changes, and personal memories.

With a sincere interest in bridging “gown and town” through community engagement, I undertook these projects for a host of reasons: job expectations (a Research I institution, the University of Cincinnati (UC) expects faculty to engage with the community), intellectual stimulation, the desire to complete relatively short-term projects, the joy of original research, the satisfaction of detective work, making a difference outside of the classroom, and personal fulfillment. Although I earned modest honoraria for the gallery exhibition and several of the library talks, most of this work received no monetary compensation.

My work on illustrated sheet music diverges from my primary research area on African American art. It began with three chance encounters. The first was while I was a predoctoral fellow in Washington, DC, at the National Museum of American Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), during 1990 and 1991. There I met another fellow, Saul Zalesch, who collected sheet music for their covers. I was intrigued by this world of illustration, which was then relatively unexamined.

The next prompt came in the fall of 1992, after I began teaching at the university. At a garage sale one afternoon in northern Kentucky, I found many boxes of old sheet music, some of it with racist imagery. I pulled a few of these aside, wanting to show them to my classes so that students could hold examples of material culture in their hands and viscerally understand what black artists had to combat on a daily basis. The woman selling items was tired because it was getting near dinner time, and she told me to take everything for free.

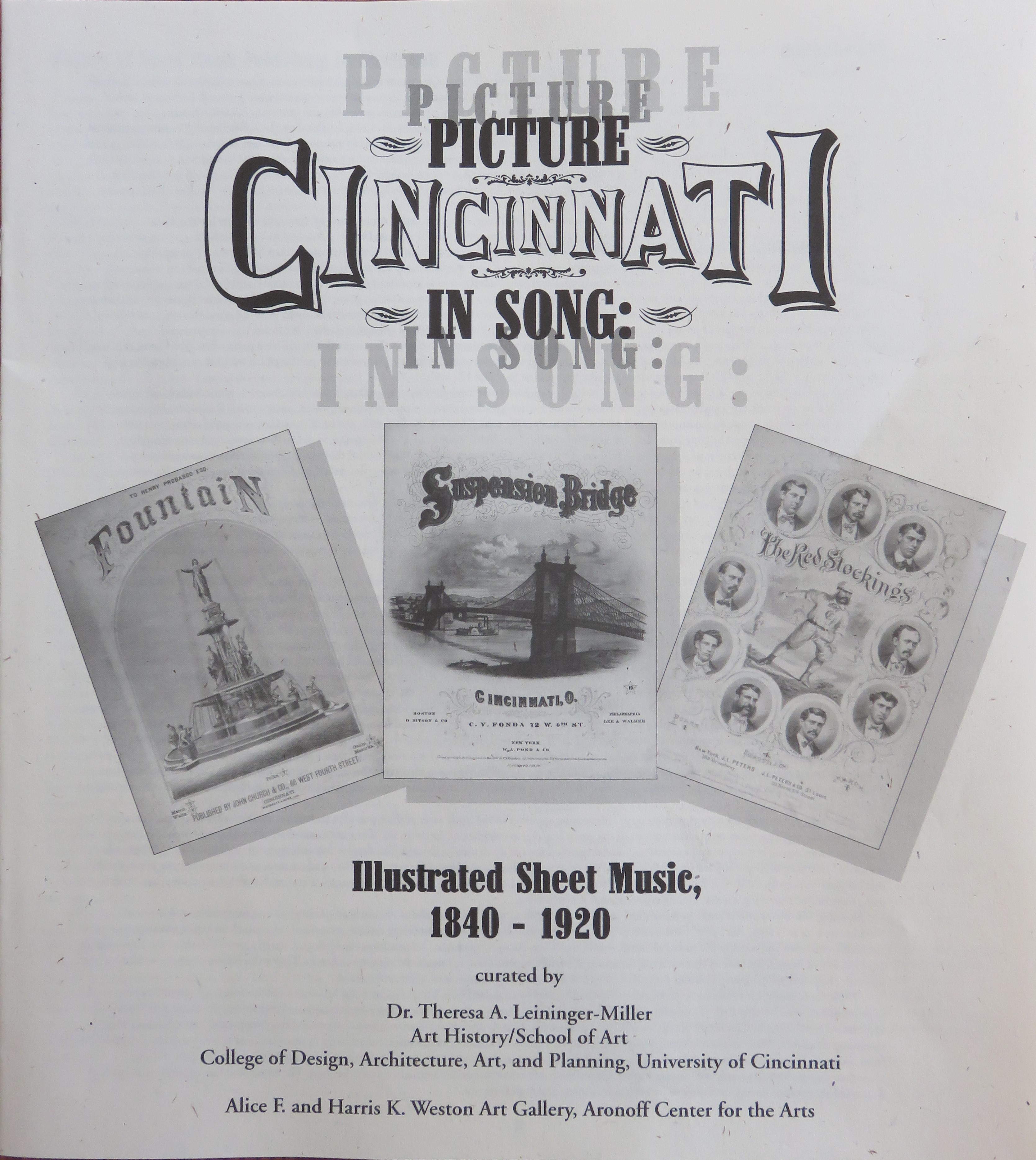

A few years later, a new exhibition space was about to open in the heart of downtown Cincinnati in the restaurant and theater district, the Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Art Gallery in the Aronoff Center for the Arts. Director Salli Lovelarkin asked if I would curate the inaugural show, launching the space simultaneously with a performance by the May Festival Chorus, the oldest choir and choral festival in the western hemisphere, originating in 1873. She loved the idea of using my recent acquisition. My collection, however, was an eclectic one developed over time by several generations of a family; it was well used and much of it was in poor condition. I began scouting around and found that the main branch of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County (PLCHC) has a remarkable, very large collection of sheet music dating from about 1829 to 1943, many with vibrant chromolithograph covers. The library had received them as a donation several decades earlier, and most had never been on public view. There was also a modest amount of relevant material in the Cincinnati Historical Society. There was a good number of compositions referring to local landmarks and institutions, as well as many that had been published locally. The exhibition, which opened in 1996, was titled Picture Cincinnati in Song: Illustrated Sheet Music, 1840–1920 (fig. 1).

Since this time, I have curated five more exhibitions of illustrated sheet music for four separate venues, all in my hometown of Cincinnati, and often in conjunction with particular events or dates. These were: America, Here’s My Boy: Mothers of Soldiers in World War I Illustrated Sheet Music (2017; fig. 2); The Angel of No Man’s Land: Red Cross Nurses in World War I Illustrated Sheet Music (2017); The Wearing of the Green: Irish Identities in American Illustrated Sheet Music, 1840 (2015; fig. 3); The Drummer Boy of Shiloh: Illustrated Sheet Music of the Civil War (2013); and “My Castle on the Nile”: Illustrated Sheet Music by Black Composers, c. 1828–43 (2011). The first two were mounted in May during the centennial of World War I, in recognition of the International Red Cross Week and National Nurses Day; the third opened in March to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day; and the fourth commemorated the sesquicentennial of the Civil War. The exhibitions appeared at the main public library and at the UC Langsam and Blegen libraries. I also exhibited reproductions at two additional locations, the American Red Cross regional headquarters and the Lloyd Library and Museum, which is dedicated to medical botany, pharmacy, eclectic medicine, and horticulture. This latter institution was then hosting the Ohio Academy of Medical History conference.

The goal of these exhibitions was to connect both nonacademics and scholars with historical material and the ways in which images of ethnicity, gender, place, race, and war are always relevant. To facilitate discussion, I delivered eleven multimedia public presentations, incorporating YouTube performances of songs with PowerPoint talks, at a wide variety of places: downtown and suburban libraries, the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, graduate seminars on feminism and music history, the Cincinnati Civil War Round Table group, the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (for seniors), the William Howard Taft Birthplace National Historic Site, Issues, an African American television program on WLW-TV (Channels 5 and 24) in Cincinnati, three radio stations (WNKU, WVXU, and WMKV), and at ten professional conferences.1 The conference presentations expanded my exhibition research to address additional subjects, such as African American soldiers in WWI sheet music, and cowgirls and adventurous women on early twentieth-century music covers. I shared my research at such events to get more mileage out of it, to seek feedback from scholars in other disciplines, and to add a layer of peer review.

It was a thrill to work in the archive late on summer evenings, when parking was free downtown. The library was open until nine o’clock at night, and my husband was home to tend to our two sons. I began my work in the mid-1990s before the collection was digitized. The card catalogue was of little use, organized by composer or composition title, with no mention of imagery, illustrator, or theme. Even in digital form, such categories are still not searchable. I went through hundreds of cardboard boxes filled with loose sheet music, much of it marked by dirty hands, and some of it in poor condition. In a spiral notebook, I wrote down song titles and locations. Boxes were organized by year and then alphabetically, such as “1927, A–G,” and there were hodgepodge groupings in bound volumes from private collectors. The only way to discover compelling covers was to look at every piece (over ten thousand of them!), then remember them by taking notes, paying for photocopies, and shooting slides. My strategy was to gather as many images as possible about a given theme and let the material speak for itself. As I grouped similar illustrations, patterns emerged, and I used composition titles as exhibition titles.

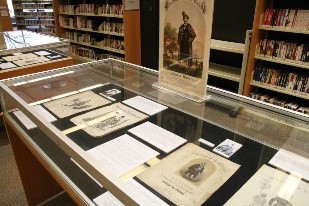

My installation at the main public library featured cover images and contextualized them with additional materials. In glass cases, I included historical photographs of composers, lyricists, performers, and illustrators gleaned from Google images. Label parameters at the PLCHC were strict, allowing a maximum of six to eight closed pieces of sheets music or three to four open volumes in a given case, one narrative label of 175 words per case, and identifying labels limited to bibliographic information only, all in twenty or twenty-four point font. There was no budget for mats, frames, easels, lighting, or props. I had no research assistants, I transcribed all the lyrics myself, and there was no editor for the labels. I loved my independence, but could have benefitted from an extra pair of discerning eyes and a sounding board for ideas. Perhaps one of the most challenging factors was space; the cases were spread over three floors throughout the main library, in the Cincinnati History room, and near the elevators, so my exhibitions lacked visual coherence. The library staff was enthusiastic and helpful, however, aiding with the graphic design, publicity/marketing, and programming, posting stories on the website, and arranging for interviews on local radio and television shows.

Curating for libraries does have limits in terms of critical reception and dissemination; although there were press releases and news stories, there were no additional venues, no reviews, catalogues, or symposia in conjunction with my exhibitions. Popular material culture is part of visual culture and displays of it broaden our field in exciting ways, but it does not have the prestige of fine art exhibitions in art museums. There are two lasting products, however. One is the print catalogue from Picture Cincinnati in Song: Illustrated Sheet Music, 1840–1920 (Cincinnati: Aronoff Center for the Arts, 1996). The other is a “Downloadable Book,” or “Virtual Library Download,” of a portion my exhibition, My Castle on the Nile”: Illustrated Sheet Music by Black Composers, c. 1828–1943, on the PLCHC website. The library posted thirty color reproductions of the sixty-eight works that were in the exhibition, but without my knowledge, input, or selection. It did not do this for the other two shows I curated there.

Such public scholarship was stimulating and enriching for me professionally and personally, and it led to many opportunities. It also led to spirited, appreciative conversations with people from various walks of life, and gave me a renewed sense of agency because I controlled most of the process and was able to complete each project in less than half a year. I also had a positive feeling of worth by connecting to the general community beyond the ivory tower. Furthermore, the work increased publicity and visibility for my program, school, college, and university, and strengthened the ties of UC to other local institutions.

This social engagement, which has both academic and public value, did contribute to my promotion to full professor, perhaps because it was above and beyond my core professional responsibilities and main scholarship. In 2019, we updated our School of Art Reappointment, Promotion, and Tenure document and made sure to include language about curating exhibitions and various forms of public outreach. Nevertheless, such work still has second-class status; the emphasis is on measurable outcomes. In order for public scholarship to be more valued by university administrators, there will have to be a way of measuring success, perhaps by calculating the visitors, news stories, reviews, website hits, and citations of catalogues, but such bean counting can be superficial. Alternatively, there needs to be an increased recognition and understanding of the intangible value of community interaction, education, and enrichment.

Cite this article: Theresa Leininger-Miller, “Library and Gallery Exhibitions as Public Scholarship: Public Engagement with Images of Ethnicity, Gender, Place, Race, and War in Illustrated Sheet Music,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2283.

PDF: Leininger-Miller, Library and Gallery Exhibitions as Public Scholarship

Notes

- Conference presentations included “Illustration Across Media: 19th Century to Now,” Washington University, St. Louis (2019); “Cultures of War: 1618/1918/2018” Cincinnati Art Museum (2018); Midwest Art History Society, Indianapolis (2018), Chicago (2016), and Grand Rapids (2011); College Art Association, Los Angeles (2018); “Branding the West” (2016) and “Illustrating War: The Aesthetics and Ethics of Representation” (2011), both at Brigham Young University Museum of Art, Provo; and the National Council for Black Studies, Cincinnati (2011). ↵

About the Author(s): Theresa Leininger-Miller is Professor of Art History at the University of Cincinnati